3 minute read

Parallelism and DOF

There are several factors that influence depth of field. One of them is the distance from the subject to the camera. As the subject moves away from the camera, depth of field increases. Conversely, as the subject moves closer to the camera, depth of field decreases. This is true for any focal length lens.

When doing macro photography or when using a long lens to capture subjects fairly close to the camera, the distance factor is very important in determining how much of the subject is in focus. Consequently, the angle the camera is held relative to the plane of the subject becomes very relevant.

To illustrate this point, look at the picture below and notice the depth of field. Most of the butterfly is sharp except the ends of the antennae and the furthest tips of the hind wings (red arrows). The reason this happened was because the camera was angled relative to the plane of the wings.

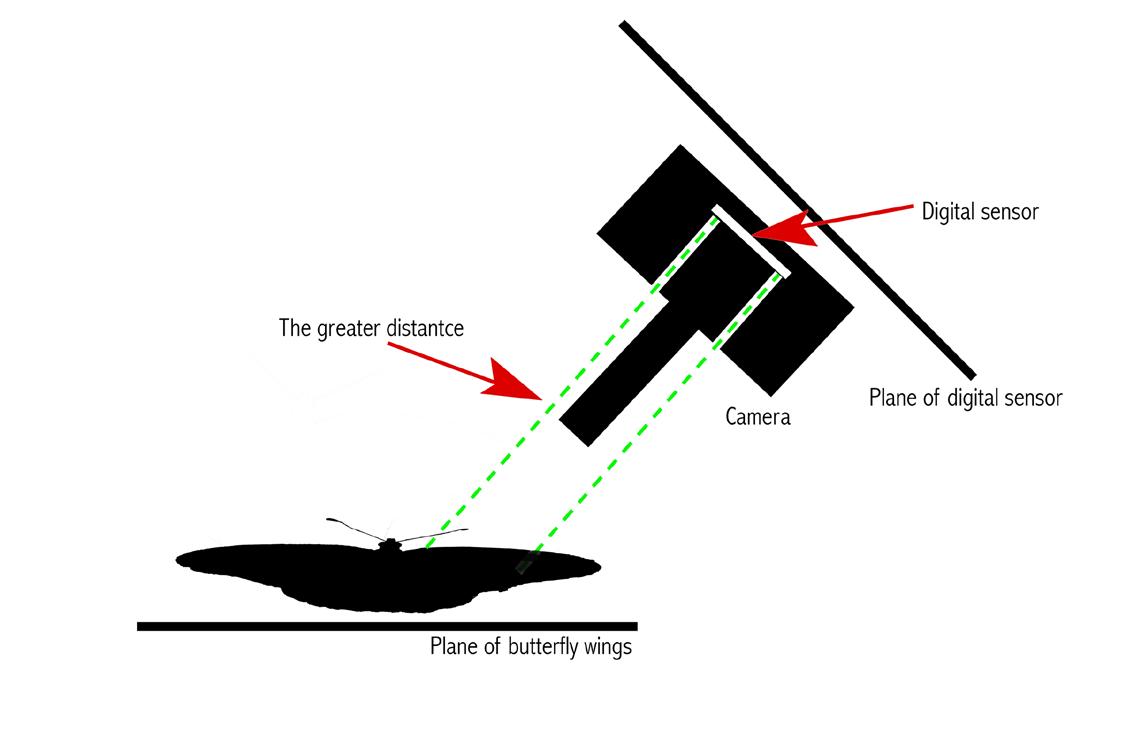

As you can see in the graphic on the next page, the plane of the digital sensor was oblique to the plane of the butterfly’s wings. Therefore, over the surface of the sensor the distances to the subject varied. The dashed green lines represent

this. Light traveled further from the butterfly’s wing to the far left corner of the sensor than it did to the far right corner of the sensor. This variance contributes to limiting the amount of depth of field in an image.

In the closeup shot on the next page of a pearly crescentspot butterfly, I used a relatively large aperture of f/8. However, the entire butterfly is sharp because I slowly positioned myself over the insect so the back of the camera (i.e. the plane of the digital sensor) was parallel with the wings.

This works, of course, if the subject is flat. If you are photographing a small turtle with a rounded shell, making the back of the camera parallel with the subject won’t increase the depth of field. raphy tours I’ve led is when we are in the field and I explain to clients about making the plane of the digital sensor parallel with a flat subject, it’s hard for some people to do that. As I stand off to the side and watch the client taking a closeup, I can see the two planes are not parallel with each other.

Therefore, I suggest you practice at home without the pressure of having to shoot quickly. Use a tripod and set the camera parallel to a leaf, a rock face, tree bark, or whatever is handy. Lock the camera in place and step away from the tripod to view the camera from the side. In this way, you can see how close you are in making the plane of the digital sensor parallel with the surface you are using. Do this a few times until you feel confident you’ll be able to angle the camera for maximum advantage.

One of the things I’ve noticed on the photog- Sometimes it’s not possible to make the two

planes perfectly parallel. For example, butterflies are so sensitive to movement that if they see your form moving over them, they will immediately take flight. Even if you can change the angle from severely oblique to moderately oblique, you will affect the depth of field in your favor.

Ideally, a small lens aperture and moving back from the subject helps a great deal in achieving the depth of field you want. But if you are using a long lens with limited DOF and/or if the working distance to the subject is close, f/32 won’t produce as much depth of field as you might think. The chameleon at right, for example was taken with f/32 and look how the rear of the reptile became soft. Had I moved back a few inches or angled the camera differently, I could have shown the entire animal with sharp detail. §