16 minute read

Hasnain Aly (Year 12

Evaluating the Appropriateness of Early Detection/Treatment and Prevention Initiatives for Cancers in NSW

Hasnain Aly (Year 12)

Advertisement

The Illawarra Grammar School, 10/12 Western Avenue, Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 2500

What Is Cancer?

Cancers are a group of diseases characterised by abnormal and uncontrolled cell division which results in the development of tumours (WHO 2019). Cancerous, or malignant, tumours are tumours that spread to other parts of the body, usually nearby tissue, but can spread through the cardiovascular or lymphatic systems, reaching distant regions in a process known as metastasis. Cancers are categorised by the area within which they develop. For example, kidney cancers are one of the most likely to metastasise, commonly spreading to the liver or lung (NCI 2020). These secondary cancers still consist of cancerous kidney cells, not liver or lung cells.

What Causes Cancer?

Cancers are caused by genetic mutations affecting the process of cell division. These mutations result in cells reproducing without being signalled to, or cells incorrectly receiving signals to cease division and/or undergo apoptosis (NCI 2020). Genetic mutations may arise at random, from genetic damage due to exposure to carcinogenic substances, or are inherited. Approximately 5% of cancers are inherited, the rest being sporadic (NCI 2018).

Risk Factors For Cancers

Age is a significant risk factor for developing cancer that cannot be avoided. The probabilityof cancerous mutations occurring increases over time . Other risk factors include chronic illnesses, lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol, infection with certain viruses, e.g. Human Papilloma Virus or Epstein Barr Virus, or hormonal factors such as increased oestrogen levels, which all impact particular age groups. In order to minimise the health and economic costs of cancer, early detection, treatment and prevention are all important paths of action (Drexler, 2019). In order to efficiently target these approaches, resources for particular cancers should be directed at the age groups where they will have the greatest impact. These may include targeted measures such as preemptive screening programmes, early interventions and educational campaigns.

Research Aim and Questions

As a result of the background research conducted in this study, it has been demonstrated that age is a significant risk factor in the development of cancers, and as it cannot be controlled, its unavoidable influence on the prevalence of cancer should be strategically combatted.

Research Aim

This study aims to evaluate the suitability of early screening, treatment and prevention measures for three different types of cancers through examining trends in prevalence in types across age groups. To achieve this, trends in prevalence of three specific cancers across age groups will be identified and compared to current cancer initiatives in order to evaluate them.

Research Questions

What are trends in prevalence of three types of cancers across different age groups? Do these trends support existing early detection, treatment and prevention programs?

With advances in modern medicine, the prevalence of infectious diseases in developed nations has significantly reduced, leaving non-infectious diseases to place a significant burden on the healthcare systems of such nations. It is widely accepted that early detection, treatment and prevention of any disease is extremely beneficial both for patients and the healthcare system. Not only does it carry economic benefits, but it also reduces the physical and psychological discomfort for patients and their carers (NIB, 2021). These benefits are extremely relevant in relation to cancers, due to the significant reduction in cure rates and increased treatment required if cancers are not detected or treated early in their development (Drexler, 2019).

Risks of Preemptive Screening

While pre-emptive screening may be beneficial for the early detection of cancer, there is also the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, which varies between different cancers. Overdiagnosis occurs when screening detects an abnormality that would not actually cause a problem for the patient, for example non-malignant breast masses. Overtreatment occurs when a cancer is unnecessarily treated, resulting in treatment toxicity and unnecessary medical costs. Both overdiagnosis and over screening can cause significant psychological and physical consequences, as well as placing unnecessary burden on medical providers. An example of this problem is in the case of prostate cancer screening. Basch et al, in their extensive 2012 study recommended that PSA screening for prostate cancer be discouraged for men with a life expectancy less than ten years as harms outweigh potential benefits. The specific harms include complications from unnecessary biopsy and treatment (surgery or radiotherapy). These recommendations were made on the basis of evidence from five large randomized clinical trials, which was then evaluated by a panel of clinical experts and published in a leading peer-reviewed journal, making their findings extremely reliable and valid. Basch et al’s paper strongly recommended that patients to be provided with sufficient information to provide informed consent for PSA screening. Information should be available in simplified language for patients. Gøtzsche and Nielsen’s 2006 study on the risks and benefits of mammography screening for breast cancer went as far as to provide such an information sheet within the paper for clinical use.

Study Methodology Data Source / Collection

Data for this study has been sourced from The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Cancer Data in Australia 2021: Book 1a – Cancer incidence (age-standardised rates and 5-year age groups). This source of data is highly valid and reliable as it originates from a government organisation, and contains an extensive breadth of data spanning almost 40 years.

Chosen Cancers

Research was conducted into cancers with established screening programs within Australia. Three cancers (breast, cervical and prostate) were selected due to their applicability to the research question and the researcher’s personal interest. Both breast and cervical cancers are the targets of extensive early detection and prevention programs within Australia, allowing their analysis to yield insightful results. Additionally, analysing data on prostate cancer will provide an interesting perspective for a cancer where the benefits of screening are controversial and highly debated within the medical comunity.

Data Analysis Method

Data was available for five year age groups up to 90+, and all ages combined. Data was provided from 1982-2021, but data from 2018-2021 is expected prevalence rather than observed. Due to this, the five most recent years with observed data (2013-2017) were used for data analysis. The means of each age group’s age specific incidence rates across the five years were calculated and plotted in a frequency histogram. The mean was used as the chosen method of centrality due to the unskewed nature of the data set.

Hypothesis and Expected Outcomes Hypothesis

Data analysed will strongly support existing initiatives for early screening/treatment and prevention as the data source is highly reliable, and Australia is a highly developed country with extensive healthcare systems.

Null Hypothesis

Data analysed will not support existing initiatives for early screening/treatment and prevention. If the null hypothesis is accepted by analysis of data in this study, this would indicate errors in study methodology, as initiatives for early screening/treatment and prevention are backed up by extensive professional data analysis and research.

Criteria to be Evaluated Against

The appropriateness of initiatives for early detection/treatment and prevention will be evaluated for how well they align with the data analysed. The ages of highest incidence of the chosen cancers will be compared to the ages where screening or prevention initiatives are targeted, which will be used to a judge their appropriateness. Additionally, current scientific knowledge will be considered when evaluating initiatives to consolidate analysis of data.

Findings

Raw data tables for the three chosen cancers are available in appendices.

General

A significant finding yielded in this study is that the incidence rates of all cancers have followed a consistent trend of increase over the past 40 years, even when adjusted for population (figure 1). As this is not the focus of this study, it will not be investigated further, but could be a focus for future research.

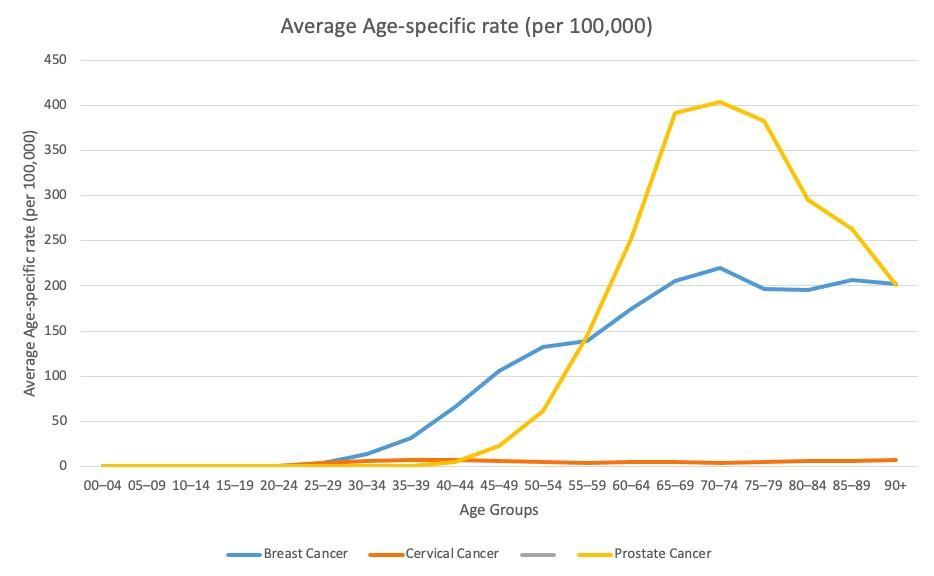

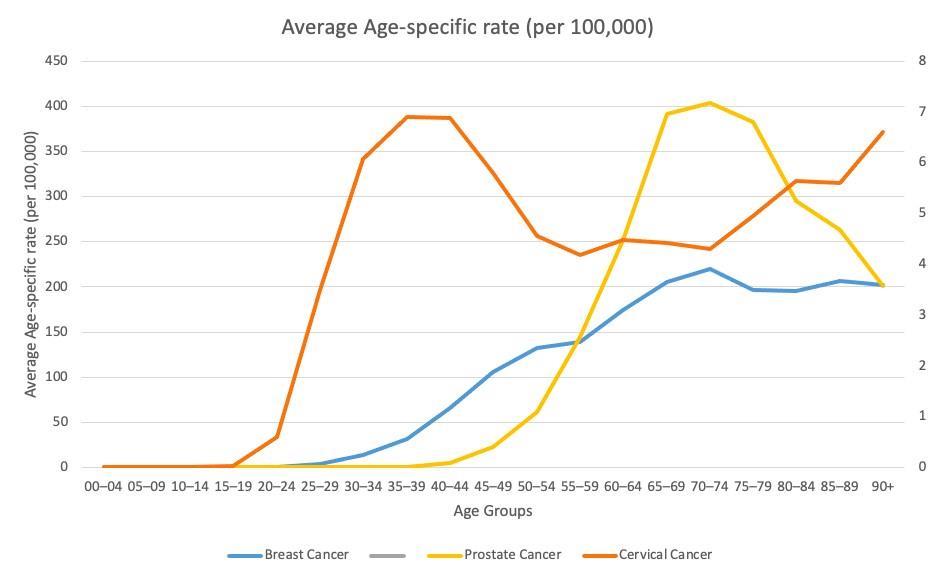

Figure 1: Incidence rates for all cancers 1982-2021, adjusted for population. Note that dotted line represents projected data. When analysing incidence rates for the three chosen cancers, it was found that that cervical cancer has a significantly lower incidence compared to the other two cancers (figure 2).

Figure 2: Age specific incidence rates for chosen cancers 2013-2017.

Figure 2.5: Age specific incidence rates for chosen cancers 2013-2017 with cervical cancer graphed on secondary axis. Also demonstrated in figure 2, both breast and prostate cancer peak in incidence between 70-74 years (although prostate cancer is around double that of breast cancer), compared to the average peak for all cancers at 85-89 years (figure 3). Cervical cancer peaks in incidence at an even younger age 35-39 (figure 2.5).

Figure 3: Age specific incidence rates for all cancers 2013-2017.

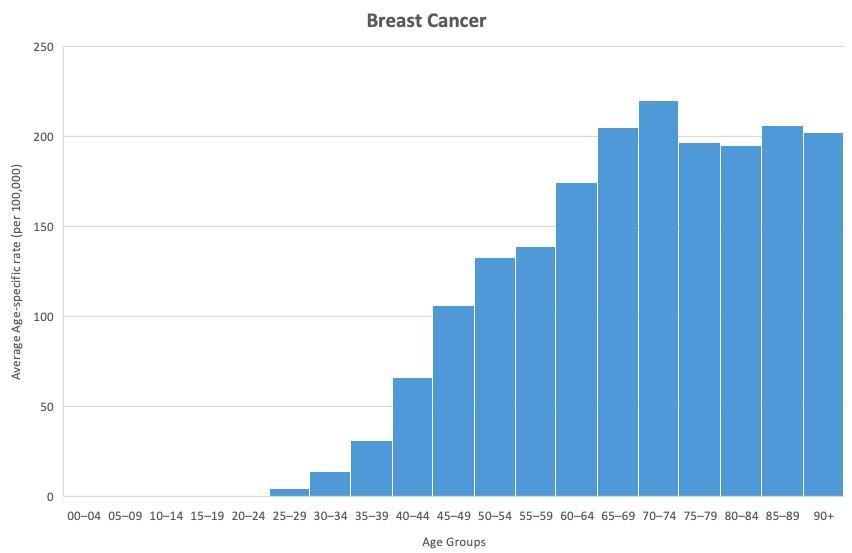

Breast Cancer

Figure 4: Age specific incidence rates for breast cancer 2013-2017. The Australian Cancer Council, Australia’s leading cancer charity, recommends screening mammography to be conducted every two years from ages 50-75. Additionally, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, America’s leading group of medical professionals specialising in women’s health, recommends that mammography screening should take place every one to two years starting from age 40, no later than age 50. They also recommend that screening continue until at least age 75. This advice from two major authorities in the field of breast cancer is heavily supported by the analysis of data, which shows a strong increase in incidence around ages 45-49, which continues to increase until ages 70-74, before plateauing (figure 4). In Australia, free mammography screenings are available for women aged 40 and over, and letters of invitation are sent every two years to women aged 50-75. This initiative strongly aligns with the trends seen in figure 4. Furthermore, stopping screening invitations at age 75 is highly supported by current scientific knowledge, with a 2011 paper from Ellen Warner published in the New England Journal of Medicine estimating that only two deaths per 1,000 would be prevented by screening women of the age of 70 to 74 years, and little to no evidence suggesting benefits of screening beyond the age of 74. This evidence strongly supports Australia’s early detection and treatment program.

However, mammography screening for breast cancer carries risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and while it does carry benefits, the level of benefit is unclear (Gøtzsche & Nielsen, 2006). It was estimated by Gøtzsche and Nielsen that mammography screening for breast cancer reduces mortality by 15%, but causes 30% overdiagnosis, and that 10% of women who have mammography screening for breast cancer will suffer psychological distress due to false positives. Based on this study, and other previously discussed studies on the risks of overdiagnosis, it is strongly recommended that women receiving mammography screening are fully informed of its risks and benefits. The researcher would like

to direct readers to Gøtzsche and Nielsen’s information sheet in their paper for more information and advise that women be provided with such a resource when offered mammography screenings.

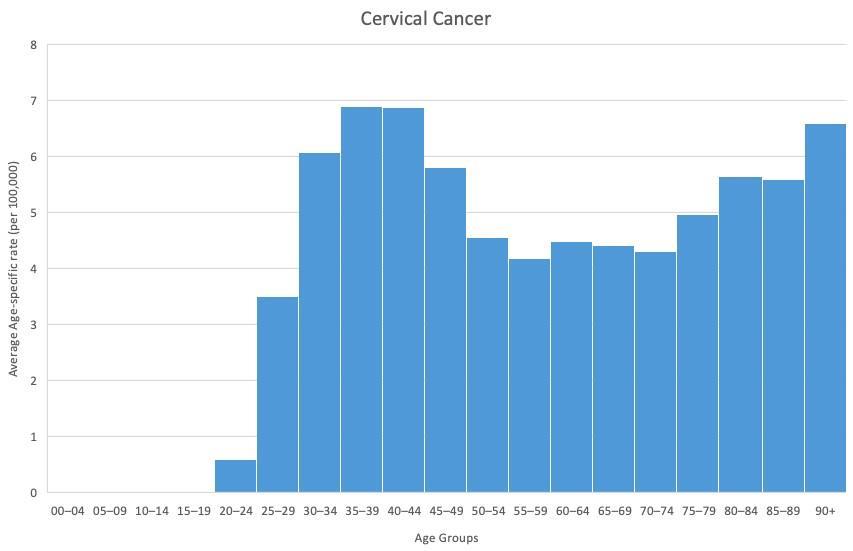

Cervical Cancer

Figure 5: Age specific incidence rates for cervical cancer 2013-2017. The World Health Organisation (WHO) advises that over 95% of cervical cancers are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is sexually transmitted and affects the majority of sexually active individuals, with about 90% of cases clearing up spontaneously. Furthermore, cervical cancers take around 15-20 years to develop in otherwise healthy women. This information aligns with the analysis of data, as incidence begins to increase at around 20-24, spiking significantly from 30-49. This indicates that women who became infected with HPV in their youth while they were sexually active will only show symptoms of cervical cancer around 15-20 years down the line. In order to prevent HPV related cervical cancer, the Australian government introduced a school based HPV vaccination program for females aged 12-13, which was modified to include males in 2017. Additionally, Australia offers free cervical cancer screenings for women aged 25-75 every five years. Australia as a country has been at the forefront of the fight against HPV and cervical cancer since the 1970s (Stenhouse, 2016), and it was only in 2020 that the World Health Assembly adopted a global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer. This strategy consists of a three staged prevention, including HPV vaccination for girls aged 9-14, and screening for women aged 30 and over. This approach has proven to be highly successful, with a highly reliable 2007 epidemiological study from Kevin A Ault finding that administering HPV vaccine in women “could substantially reduce the incidence of HPV16/18-related cervical precancers and cervical cancer”. Not only did this study consist of a large sample size (n=20,583), but it was also randomised, controlled (with a placebo group), and double blind. The appropriate methodology results in the conclusions of this study to be considered extremely valid and reliable.

Australia’s initiatives for combating cervical cancer through early detection and prevention (HPV vaccine) are supported by the analysis of data in this study, as well as current scientific knowledge.

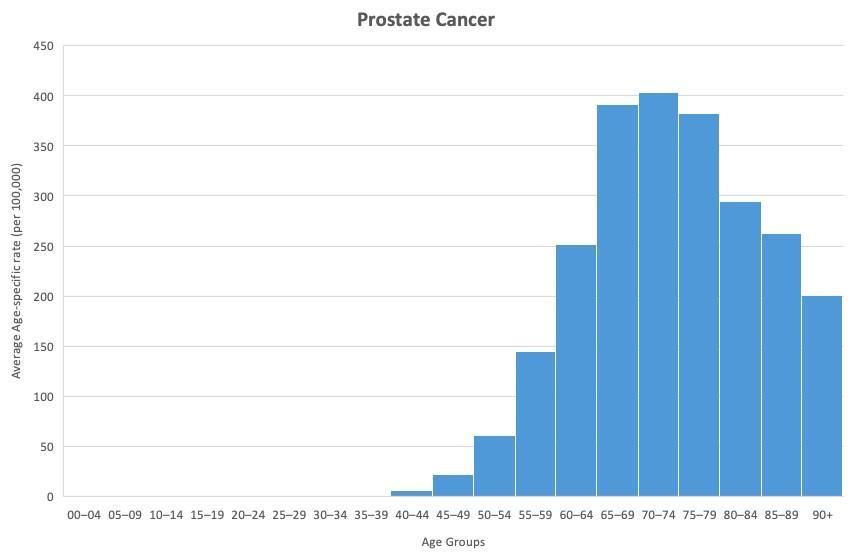

Prostate Cancer

Figure 6: Age specific incidence rates for prostate cancer 2013-2017. The Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia (PCFA) statesthat approximately 50% of males will have some form of prostate disease before age 70. Australia has one of the highest incidence of prostate cancer rates globally, with one in seven Australian men being diagnosed with prostate cancer during their lifetimes. Furthermore, it is also the second most diagnosed cancer and the third most fatal cancer in Australian men (Cancer Council Australia, 2020). This is supported by analysis of data, where the incidence rate of prostate cancer was significantly higher than other cancers, including breast cancer Prostate cancer has been the recipient of significant misconception surrounding early detection screening, possibly due to the invasive nature of the digital rectal examination (DRE), which is no longer recommended for routine screening as it only helps detect tumours near the rectum. The prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test is generally employed to test for an antigen produced by the prostate gland, higher levels of which may indicate some form of prostate disease (Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia 2021). However, PSA testing is problematic as it does not definitively test for prostate cancer, and may present false positives due to other prostate diseases. It can also overdiagnose low-risk prostate cancers, resulting in unnecessary treatments with potential harmful side effects and psychological distress for patients and their family (Basch et al., 2012). Due to these potential risks, guidelines recommend that PSA testing is appropriate for men aged 40/4569 with a family history, and ages 50-69 without family history. Additionally, screening over the age of 70 carries a significantly increased risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. This advice aligns with the analysis of data as incidence begins to rise throughout 50s

Conclusion

This study aimed to evaluate the suitability of early screening, treatment and prevention measures for three different types of cancers through the examination of trends in prevalence in cancer types across age groups and consolidating with current scientific knowledge. Throughout this report, a comprehensive evaluation has demonstrated the high suitability of Australia’s early screening, treatment and prevention measures for three selected cancers, resulting in the acceptance of the hypothesis.

Bibliography

A Pray, L 2008, Errors in DNA Replication | Learn Science at Scitable, Nature.com, Nature Education, viewed 28 March 2022, <https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/dna-replication-and-causes-of-mutation409/#:~:text=Nonetheless%2C%20these%20enzy mes%20do%20make,every%20time%20a%20cell%20divides!>. ACOG 2017, Mammography and Other Screening Tests for Breast Problems, Acog.org, viewed 7 April 2022, <https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/mammography-and-other-screening-tests-for-breastproblems>. ACRF 2021, Types of Cancer | What Are The Different Types of Cancer | ACRF, ACRF, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.acrf.com.au/support-cancer-research/types-ofcancer/?gclid=CjwKCAjwrfCRBhAXEiwAnkmKmR_IlLgFuXcqdUUvknw8Z6 tRfISyCEpCZ8CCXVIjND1Laz_SovjgRoCMBIQAvD_BwE&fwp_load_more=2>. AIHW 2020, How healthy are Australians? - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, viewed 4 May 2022, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australiashealth/how-healthy-are-australians>. AIHW 2021, Cancer data in Australia, Cancer incidence by age visualisation - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/cancer-incidence-by-agevisualisation>. Ault, KA 2007, ‘Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like-particle vaccine on risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, grade 3, and adenocarcinoma in situ: a combined analysis of four randomised clinical trials’, The Lancet, vol. 369, no. 9576, pp. 1861–1868, viewed 6 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17544766/>. Autier, P & Boniol, M 2018, ‘Mammography screening: a Major Issue in Medicine’, European Journal of Cancer, vol. 90, pp. 34–62, viewed 4 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29272783/>. Basch, E, Oliver, TK, Vickers, A, Thompson, I, Kantoff, P, Parnes, H, Loblaw, DA, Roth, B, Williams, J & Nam, RK 2012, ‘Screening for Prostate Cancer With Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion’, Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 30, no. 24, pp. 3020–3025, viewed 6 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22802323/>. Beard, J 2019, Info, PSA Testing, viewed 27 April 2022, <http://psatesting.org.au/info/>. Cancer Council Australia 2017, Early detection and screening, Cancer.org.au, viewed 25 April 2022, <https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/causes-and-prevention/early-detection-andscreening>. Cancer Council Australia 2020, Mammogram, Cancer.org.au, viewed 7 April 2022, <https://www.cancer.org.au/mammogram>. Cancer Council Australia 2022, Early detection of prostate cancer, Cancer.org.au, viewed 25 April 2022, <https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/causes-and-prevention/early-detection-andscreening/early-detection-of-prostate-canc er>.

Drexler, M 2019, The Cancer Miracle Isn’t a Cure. It’s Prevention., Harvard Public Health Magazine, Harvard Public Health Magazine, viewed 31 March 2022, <https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/magazine/magazine_article/the-cancer-miracle-isnt-a-cure-itsprevention/>. Gøtzsche, PC & Nielsen, M 2006, ‘Screening for breast cancer with mammography’, in PC Gøtzsche (ed.), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, viewed 6 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17054145/>. Australian Government Department of Health 2019a, BreastScreen Australia Program, Australian Government Department of Health, viewed 25 April 2022, <https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/breastscreen-australia-program>. Australian Government Department of Health 2019b, National Cervical Screening Program, Australian Government Department of Health, viewed 25 April 2022, <https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-cervical-screening-program>. http://canceraustralia.gov.au 2020, HPV immunisation, National Cancer Control Indicators, viewed 27 April 2022, <https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/screening-and-immunisation/immunisation/hpvimmunisation#:~:text=In%202007%2C%20the%20s chool%2Dbased,include%20male%20students%20in%202013.>. http://www.canceraustralia.gov.au 2019, Health professionals | Cancer Australia, Canceraustralia.gov.au, viewed 28 April 2022, <https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/prostatecancer/clinicians-hub>. Mühlhauser, I 2007, ‘Ist Vorbeugen besser als Heilen?’, Zeitschrift für ärztliche Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen - German Journal for Quality in Health Care, vol. 101, no. 5, pp. 293.e1–293.e9, viewed 4 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17711254/>. National Cancer Institute 2020, Metastatic Cancer: When Cancer Spreads, National Cancer Institute, Cancer.gov, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.cancer.gov/types/metastatic-cancer>. NCI 2015, Risk Factors for Cancer, National Cancer Institute, Cancer.gov, viewed 28 March 2022, <https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk>. NCI 2022, Dictionary of Cancer Terms, National Cancer Institute, Cancer.gov, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cancer>. NCI 2020, Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2020 available now | NCIRS, Ncirs.org.au, viewed 27 April 2022, <https://www.ncirs.org.au/annual-immunisation-coverage-report-2020-availablenow>. NHMRC 2014, PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer in Asymptomatic Men Information for Health Practitioners, NHMRC, March, viewed 8 May 2022, <https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/reports/clinical%20guidelines/m en4d-psa-testing-asymptomatic.pdf>. NIB 2021, Why is prevention better than cure?, Nib.com.au, nib, viewed 4 May 2022, <https://www.nib.com.au/the-checkup/prevention-is-better-than-cure>. NCI 2021, What Is Cancer?, National Cancer Institute, Cancer.gov, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer>. Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia 2021a, Prostate cancer – a guide for newly-diagnosed men, Issuu, viewed 27 April 2022, <https://issuu.com/prostatecancerfoundationaus/docs/pcf13457__prostate_cancer_-_a_guide_for_newly_dia>. Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia 2021b, What you need to know about prostate cancer, Issuu, viewed 27 April 2022, <https://issuu.com/prostatecancerfoundationaus/docs/pcf13452__what_you_need_to_know_about_prostate_ca>. Stenhouse, A 2016, How Australians have been leading the fight against cervical cancer since 1978 | Know Pathology Know Healthcare, Know Pathology Know Healthcare | The engine room of healthcare explained, viewed 27 April 2022, <https://knowpathology.com.au/australians-leading-cervical-cancer-fight/>.

Warner, E 2011, ‘Breast-Cancer Screening’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 365, no. 11, pp. 1025–1032, viewed 6 May 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21916640/>. WHO 2019, Cancer, Who.int, World Health Organization, viewed 25 March 2022, <https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer>.