5 minute read

A Gift of Memory and Scholarship

When Marc Lewyn’s father, Bert, passed away in 2016, and the family was observing shiva (the seven-day mourning period in Judaism), a friend asked somewhat bluntly, “How do you plan to permanently memorialize your father?”

The question stopped Marc in his tracks, not only because it came at a time of high emotion, but because Marc literally had never given it a thought. “As a professional wealth manager, I have conversations like this all the time with my clients about how to use philanthropy to lift up their highest values. Now this same important question was directed at me.”

Advertisement

It was clear to Lewyn that his father had led a remarkable life. Bert Lewyn’s redemptive story of survival during the Holocaust was foundational to Marc’s sense of self. The harrowing story was told in full when Marc’s wife Bev, a professional researcher, helped her father-in-law organize his writings and publish a memoir, On the Run in Nazi Berlin, in 2001.

Marc Lewyn knew that Rabbi Tobias Geffen kept a daily diary. “Some days the entries were quite mundane, but many were powerful, like the sermon he wrote on the night of Pearl Harbor! Like a Forrest Gump of Jewish ATL, David’s diary was a rich chronicle of the American Jewish south. The Geffen family papers were already at Emory University. I began to see that my father’s life also had lessons for humanity. Donating my parents’ papers to Emory and amplifying David’s example seemed like a fitting memorial to them.”

When Marc Lewyn toured the archives at Emory, he saw stacks of boxes, but many donations were uncatalogued. “I not only wanted my father’s and family papers to be at Emory, I wanted them to be accessible. That led to digitizing these documents so they could be available with just a click. David and I also wanted to encourage scholars to have access to these papers through the creation of the Geffen and Lewyn Family Southern Jewish Collections Research Fellowship. It supports research in the Rose Library’s holdings, documenting Jewish life in Atlanta, Georgia, and the South. It encourages students, professors, scholars, and authors to research the rich history of Southern Jewish families, culture, businesses, activism, and politics.”

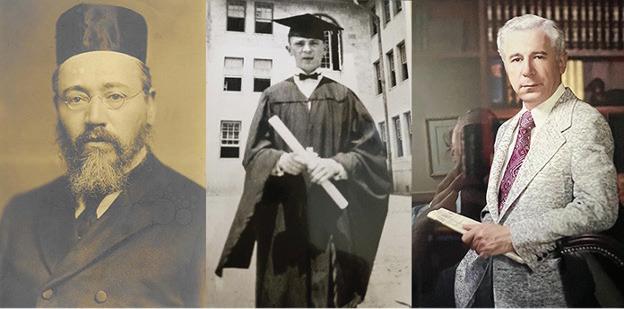

L, Rabbi Tobias Geffen, Center, Louis Geffen and R, Bert Lewyn. Anna and Louis Geffen Papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

At a recent reception at Emory University celebrating the Geffen Lewyn Fellowship, David Geffen shared the story of how when Atlantan Lois Frank was an undergraduate at Emory, she invited Dr. Martin Luther King to come to campus and speak to a group of students. He had just won the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Lois drove over to Dr. King’s home in her VW Beetle and took him to campus. Nobody knew about it and there was no security— not even the Emory campus police were aware. The event went off without a hitch, but there is no account of the meeting anywhere except in the Emory student newspaper, The Wheel,” Rabbi Geffen said.

“It underscores the value of archival material for scholarship,” Marc Lewyn says. “Researchers wouldn’t know about Dr. King’s visit to Emory unless they delved deep. Neither The Atlanta Journal nor the Atlanta Constitution reported the story, but it lives at Emory. Stories, letters, and personal memoirs are more powerful than tax benefits. I wish more people would think about that when they think about what to do with their parents’ belongings. These are our treasures!”

At 18, Bert Lewyn and his parents were taken by the Gestapo and separated. Lewyn was sent to work in the Gustav Genschow and Co. Weapons Factory in Berlin. He later learned his parents died at a Polish concentration camp. Lewyn was enslaved at the factory until 1943 when, after a tip from a nonJewish worker, he eluded a roundup of Jews and spent the next several years hiding at the homes of friends and strangers. In 1945, he was captured and imprisoned in the former Jewish Hospital in Berlin. He and a group of prisoners managed to escape through a tunnel they accessed with a key Bert made from debris found after a bombing. He returned to the apartment of friends and remained there for several weeks until Russian soldiers raided the apartment, signaling the end of the war.

Bert Lewyn’s ultimate rescue came in 1949 when his Atlanta relatives, Rabbi Tobias and Sarah Geffen, sponsored his immigration to America. At the time, Rabbi Geffen was the spiritual leader of Congregation Shearith Israel, famous not only for his prominence in the Atlanta Jewish community, but also for his famous rabbinic ruling that certified Coca Cola as kosher. The Geffens helped Bert rebuild his life and introduced him to his wife Esther. Lewyn went on to launch a successful business in Atlanta, was generous to his Jewish community, and perhaps most significanty, had children of his own, making it possible for future generations of Lewyns to come into the world.