3 minute read

Pachyderm Perfection

Producer Julia Pistor and director Wendy Rogers discuss the making of their charming new Netflix movie The Magician’s Elephant.

- By Karen Idelson -

When beloved children’s author Kate DiCamillo (The Tale of Despereaux, Flora and Ulysses) wrote The Magician’s Elephant over 10 years ago, this tale of war, grief, loss and magical realism caught the eye of a veteran producer who just wouldn’t let go of her own dream to turn it into a movie. This year, that dream comes true!

Producer Julia Pistor, whose long list of credits include the three Rugrats movies, The Wild Thornberrys, Hey Arnold! The Movie, Charlotte’s Web and The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie, initially wanted to develop the story as a live-action film through Fox. Though there were discussions of making it, but the project never came to fruition at that studio.

“When [former head of kids and family, fea- tures] Melissa Cobb came to Netflix and started a division, she met with me and asked me, ‘What’s the one that got away?’” recalls Pistor.

“I told her I loved Kate DiCamillo’s book and once she read it, boom, things got going.”

Fortunes of War

As Pistor switched her development of the book from live action to animation, it opened up new possibilities for storytell ing in terms of the style and look of the film. They were also able to be in produc tion during the pandemic, which would’ve proved more difficult for a live-action film.

Visual effects veteran Wendy Rogers pitched to direct the film, feeling that she deeply understood the story and knew the visual style that would enhance the themes. This will be her directorial debut after working on live-action films like Batman and Robin and in visual development at DreamWorks on Shrek

The project also brought together a group of notable actors for the voice cast: Noah Jupe stars as the orphaned boy, Peter; Benedict Wong voices the Magician; Pixie Davies appears as Adel, Peter’s sister. Mandy Patinkin and Miranda Richardson lend their voices to the project as well.

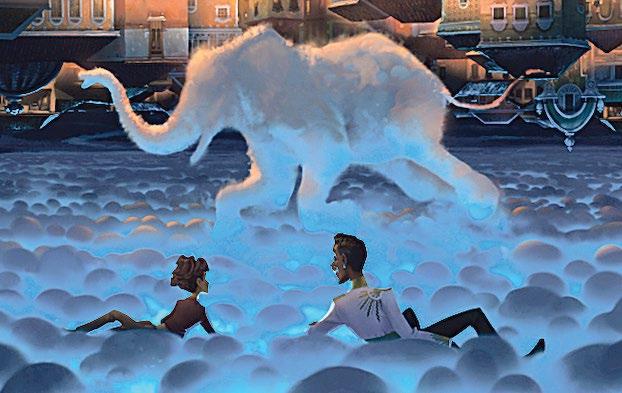

DiCamillo’s book contained elements of magical realism woven through a story about two siblings sepa- rated because of a war, and Rogers wanted to be sure audiences felt the magical elements in the film and connected with the characters. The director emphasized certain aspects of the character design to achieve this goal.

“Eyes are always so critical in character design in animation,” says Rogers. “Making sure that we get really expressive eyes, to me, is the most important thing. One of the things that I think we worked on that was a very clear goal for me and the head of animation, was that I really wanted to make sure that we had some stillness so that we would actually read the expressiveness of the eyes. We did do a quite a lot of testing early on with eye shaders, and everything else, to work out what is the right level of pupil dilation.”

Rogers points out that there are lots of controls for the animators over the structure of the actual eye. “It was all in service of that sort of nuanced emotion that we wanted to have for those moments where we could really read through the character’s eyes and facial expression,” she says. “We wanted the audience to see what they’re thinking and have that emotional connection between characters.”

As they crafted the look and design of the characters, writer Martin Hynes also developed the story to include moments that were not originally in the book. (Hynes has a story credit on Toy Story 4.)

“Martin wrote a scene in which the elephant washes itself and washes away all this colorful paint and then you see the real elephant for who it is,” says Pistor. “Wendy and the team just executed it in the most beautiful way. I love that he added that because the elephant came into the town and the people who lived there didn’t know what to do with an elephant. It was a visual moment I don’t think we could have had in any other kind of film.”

The producer and writer knew from the beginning they wanted to hang onto the challenging themes of war and loss, even though their film was aimed at children. There was never a moment where they thought it would be overwhelming if it was brought through the story in a way that felt natural for the narrative.

“We never shied away from the trauma of war that’s part of the book,” says Pistor. “I think animation can tell stories that talk about a lot of things now. It’s what Guillermo del Toro has said as well — that animation is film. In film, you can discuss difficult things like war, even in a story for children. Netflix didn’t shy away from it either.”