13 minute read

Idea generation, Modification and Development: The ISTA Journal

By Dr. Derek Pigrum

While the ISTA journal does not exist in one format, the generic term is a useful one, in that it refers to all work carried out by teachers, in relation to students reflecting on their work. Whether this be a notebook, an IB Theatre Arts Portfolio or an MYP Journal or another form that you use. As such it lends clarity to that area of our work that is focused on students generating ideas in written/visual form.

Advertisement

Introduction

This article is an attempt to locate the complexity of idea generation and development in the ISTA journal and its role in sustaining the unending effort of construction that is characteristic of creative work.

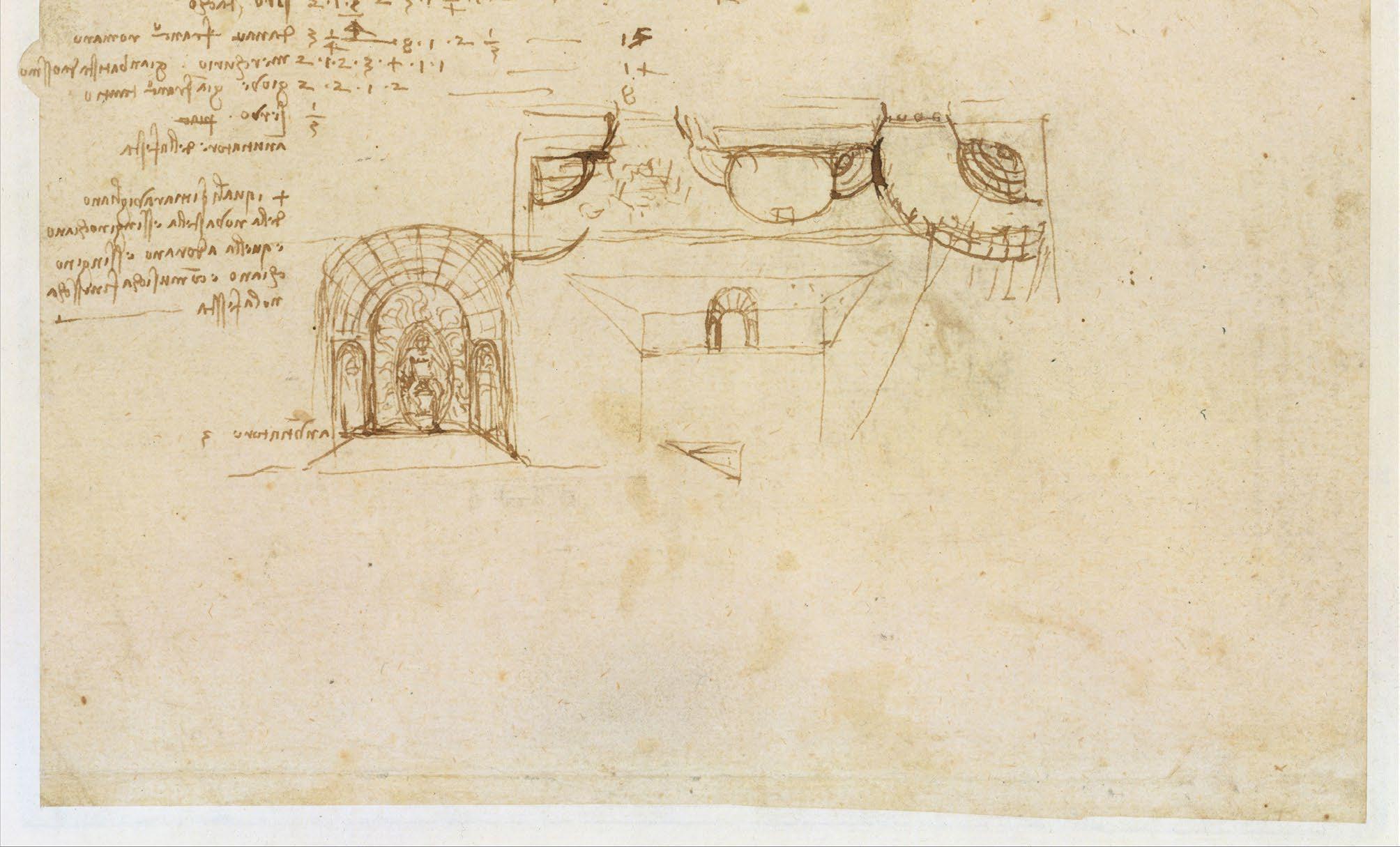

There is a correlation between the origins of the creative use of journals, the emergence of the sketchbook in the Renaissance and the role of the ‘commonplace book’ that is present in the way the ISTA journal is used by students today. In the ‘commonplace book’ students studying analysis, genesis and literary composition would enter products of individual reading and notes on style for future use, on the grounds that they would, as Bacon stated, ‘ensure copies (copiousness) of invention’ (in Dixon, 1971, p.48). In the renaissance artist’s note/ sketch book, with its drawings and writing, it became the focal point of discussion of ideas and their modification. The notebook, like the ISTA journal today, became an instrument both of guidance, interaction and control because it provided the means to discuss and illustrate ideas and changes, as well as a means to check changes and mistakes and to introduce corrections. The sketchbooks of the Medieval craftsmen were pattern books, while the sketchbooks of the Renaissance artist-engineer, like the ISTA journal, effectively constituted an experimental field (Pigrum, 2001). As we might expect, Leonardo da Vinci was a master of this process, which often involved rapidly absorbing and metamorphosing ideas by other people. But he was not alone in keeping a notebook. Galluzzi (1996) states that there are in existence one hundred and fifty notebooks by other artistengineers of the Renaissance that have never been published. The practice of copying down ideas by other people was not in the least at odds with ideas about creativity or originality based on the interplay in rhetoric and poetical composition between invention and imitation.

Perhaps one of the most important tasks facing postRomantic, expressionist and modernist theories of education in the arts is to help our students overcome what Bloom (1988) has termed ‘the anxiety of influence’. All art involves artifice. The way we approach the effort and artifice of creative construction and the quality of completed work will to a great extent be determined by the way students encounter the journal and make it their own.

Switching between Modes and Getting Things onto Paper

Journal keeping at its most effective often involves writing, drawing and other sign-mode use. In terms of creative thinking, Kress (1997) argues for the efficacy of ‘multi-mode’ use; when the limits of one mode have been reached it helps to be able to switch to another mode. In Kress’ description of ‘multi-mode’ objects very often young children use language to indicate action and sequence and ‘drawing to represent, to display’. He emphasises the temporary nature of these objects.

MacCormac states each mode is a ‘way of mediating an appropriate cognitive phase’ (in Lawson, 1997, p.142). The disposition or the freedom to shift mode helps the agent to avoid conceptual entrapment and to avoid closure. However, Kress states that these ‘multi-mode’ objects are not culturally recognised; we very seldom get to see the rough draft or manuscript of a writer or excerpts from notebooks and the rough sketches of playwrights and directors. Kress states that education divests us of the ability to use ‘multi-modes’. In subjects like Art and Design and Performing Arts there is an urgent need to encourage students through demonstration and as part of the modelling of practices by the teacher, to work in rough, in dialogue with the student.

D’Arcy (1989) and Smith (1982) writing about drafting, place emphasis on the journal, on getting things out onto paper and the central difficulty of getting students to appreciate the malleability of writing. D’Arcy actually echoes Leonardo da Vinci’s advice on compositional process when she states that ‘children need to feel they can play around with it (writing) and try things out, without worrying over much if their intention doesn’t work out in the way they expect’ (D’Arcy, 1989, p.21).

D’Arcy takes up the most difficult feature of introducing drafting processes to children. It is the attitude adopted by children of wanting to get a task ‘over and done with’ and her solution is to get children interested and involved in their own thinking processes, in meta-cognitive activity. The journal provides the teacher with something tangible, because visible, to respond to in terms of a dialogue about ideas and orientations to future action. The teacher is what D’Arcy calls ‘a partner in a learning dialogue’. The teacher’s task is to provide a framework and introduce some conventions and strategies, which enhance the student’s ability to ‘think onto paper’ and this is exactly what I believe the teacher’s role is in terms of the ISTA journal. I would agree with D’Arcy in stating that the main motivation or as Smith would say, the main ‘sensitivity’ to the journal process, comes when the student experiences the power that the journal has to sort out ideas. D’Arcy also states that the kind of pedagogy she is advocating involves a ‘multi-mode’ approach to writing:

‘Our mental capacities for shaping meaning continually interrelate, making use of whatever media happens to be at hand – verbal, visual or kinetic’ (ibid.).

D’Arcy deals briefly with the drawing mode in writing. In process writing drawing is used as a shaper of meaning, just as writing is used as a shaper of meaning. She even comments that when words are used with drawing in this way they change their character and become very condensed. She identifies the ‘holistic’ nature of drawing and our ability to take it in at a glance. But later she sidesteps some of the implications of the drawing mode for process writing and instead looks at the use of Buzan’s (1993) ‘mind maps’ that are essentially linguistic with a limited use of other signs. Harste and Short (1988) have a short section entitled ‘sketch to stretch’ which states that pupils ‘should be helped to see that shifts in communication systems help learners gain new perspectives and insights’ (Harste and Short 1988 p.356). But in general they use drawing to ‘recast’ something that has already been written and not as an integral part of the process work, or working in rough that goes on in journals.

In the poetic composition of Pushkin there is a pervasive use of drawing. Zavlovskaya (1987) states that one use of drawing in his composition process was a form of ‘exit or outlet for things he could not yet express in words’ (Zavlovskaya, 1987, p.381), a kind of intimation of things to come. This produces drawings in his manuscripts that

Kafka also used drawing as an aid to composition although many of these drawings have not been made available (Böttcher and Mitterzweil, 1982). Kafka’s use of drawing was very rapid. Max Brod collected them together, sometimes rescuing them from the wastepaper basket or cutting them from the margins of the school exercise books that Kafka used as notebooks. Some were done on postcards; many were spread throughout his prose composition. This use of drawing must not be interpreted believed to involve students in a ‘hypothetical mode’ that encourages experimentation, inquiry and the student’s active construction of Understanding.

Working in rough is something teachers often take for granted that students can do without assistance, partly because they believe that they ‘free-up’ the student by the exhortation,‘work it out in rough’. I suspect that one reason we are baffled when students have difficulties working things out in rough is that we are sometimes unrelated to the words on the page producing an antagonism between the sketch and the text; drawings produced by unexpected associations unconnected to the text he was working on. At the same time some drawings produce a graphic parallel to the text. In the rough portrait drawings that abound in his manuscripts he selected those features that immediately brought that person to life for the reader. It would seem that Pushkin used drawing to help him grasp the words he needed to describe them. In English in the Arts (1982), Peter Abbs places great emphasis on the initial exploratory stages of writing. He quotes Bowra on Pushkin’s speed and abundance of creative process but neither he nor Bowra mention Pushkin’s pervasive and interwoven alliance of drawing and writing in his manuscripts. as illustration but as integral to the drafting process. Böttcher and Mitterzweil (1982) suggest that Kafka used drawing in a playful transposition (spielerische Transponierung) of thoughts and emotions, but more importantly to initially capture the gestures, movement and appearance of the characters in his works (see also Josipovici, 1995). Both Kafka and Pushkin seemed to have an extreme sensitivity to human gestures and movement that they initially captured. in drawing.

Working in Rough

In many areas of education and particularly in the arts, students are asked to work in rough in the belief that working this way invites further thought and produces better end products because it allows for a process of development and modification. Working in rough is correctly somehow equate working in rough to an innate ability to play. Teachers, for example, often use the expression ‘play with that idea and see what you come up with’ as if to ‘play’ with ideas is an innate ability. However, playing with ideas or working in rough is high order cognitive activity characterised by erasures, cancellations, displacement and condensation and is open to modes of negation and the use of ‘multi-modes’. This is complicated by the fact that, unlike the finished piece, journal entries do not yet represent value. For the expert practitioner this value free zone is uninhibiting, but for the student it can be disconcerting.

‘Getting out of the desert’

Once ideas are displayed or, as Heidegger (1975) would say, ‘presenced’, they can be changed,abandoned, returned to, made and remade. Thus what is pulled together can be pulled apart and in this process, because what has been pulled together or apart is ‘presenced’ in drawing and writing, nothing is irretrievably lost to the mind. The ‘thingly’ character of journals is achieved by being worked on. Something worked on in order to work something out.

Heidegger developed a concept of ‘thrownness’ of projection, of sketching out. The purpose of the sketched out, has to do with wrestling something. Thus the beginning, or founding act, starts the chain of ‘could be’ states. It is what Heidegger would describe as close to thesis, of bringing forth into the unconcealed, a ‘setting up’ or ‘presencing’ in the unconcealed, which is then subject to questioning (see Heidegger, 1975). It is what Pinter refers to as his ‘given’ that ‘gets him out of the desert’ (Billington 1979). Etymologically, the relationship between writing and drawing is close. The German ‘riss’ is closely related to both writing and drawing (riss is the origin of the word ‘writing’ in English). In German the concept of wresting is related to the concept of riss, rift or incision. Reissen is to wrest. Den Riss is the design, reissfeder the drawing pen and reissbrett the drawing board, but it is the relationship of the concept of ‘to wrest’ and to draw or design or write which is of importance. Drawing and writing have a quality of projection, of ‘thrownness’ that facilitates the wresting of an idea (Heidegger, 1975). It helps here to once again return to the paradigm of poetic composition, which Heidegger describes as ‘a kind of measuring’, as an act of measuring against an unknown goal state. The importance of ‘seeing’ an idea, of placing an idea on paper before our eyes is what Heidegger (1975) relates to the process of or ‘condensing’ Verdichtung. The word for poetry in German, Dichtung, is derived from this word that seems to describe the essential process of poetic composition.

Reflective and Reflexive Monitoring of Creative Process

The ‘reflexive monitoring’ of the student’s own creative process in journals and workbooks serves the two reflective purposes Jarvis assigns to the journal; ‘first, it helps students to become reflective learners, both on- action and in-action. Secondly, it is possible to get students to examine their own self-development and their own feelings of empowerment’ (Jarvis,2002, p.127). The journal becomes an archive of observations, connections, interrelations and coincidental images, all of which can provide the basis for a restructuring of present idea development. The recording, generation, modification and development of ideas in the journal encourages experimentation and critical thinking, provides the opportunity for reflection and is a source and stimulus to dialogue. Briskman (in Dutton and Krausz, 1981) dismisses any understanding of the creative process without resource to this kind of intermediary product and the transitional processes it involves. At the same time, ‘it’ helps students to become reflective learners, both onaction and in-action. Secondly, it is possible to get students to examine their own selfdevelopment and their own feelings of empowerment’ (Jarvis, 2002, p.127).

Jarvis mentions Morrison (1996) who ‘notes that when reflective practice prospers it is seen by many students as a major significant feature of their development in all spheres.’ (ibid.).

Reflexive monitoring in the journal is an ‘enabling’ structure that enhances the student’s ability to see ‘how to go on’. As we have seen, following Wittgenstein, the pupil can ‘continue the pattern by himself’ (Wittgenstein, 1963, p.84) because ‘there exists a regular use of signposts’ (ibid., p.80). ‘Regular use’ constitutes the journal as a ‘signpost’ that becomes a ‘generative structure’ or habitus (Bourdieu, 2000). The habitus, like the notion of the ‘signpost’, does not produce, but rather orientates action by providing a practical sense of ‘how to go on’.

Conclusion

In terms of idea generation and creative thinking journal use rests on tentative, provisional reference points that constitute knowledge that is incomplete or approximate, knowledge as speculative action that constantly moves and always produces a remainder.

But how does the student ‘know how to go on’ (Wittgenstein, 1963, p.84) and ’set about taking hold’ (Derrida, 1987 p.126) in the independent context of work in the journal. Following Wittgenstein (1963), the answer would not seem to lie in a consideration of ‘the reasons for doing this or that’ but in a response to the pressure of an immediate task where working in the journal operates as what Wittgenstein terms ‘signposts’. The student goes by a signpost only ‘in so far as there exists a regular use of signposts’ (Ibid. p.80).

There is a vital link here to the work of Harré on ‘Identity Projects’ in that, by keeping a journal or note/sketchbook, the individual transforms social appropriations that enable them to ‘take over their own development’ (Harré, 1983 p.257). Harré equates the possibility of self- knowledge with ’the semiotic resources’ available to the individual but also places its development in our engagement with others. Journal use, is related to Harre’s way of formulating agency in terms of ‘powers to be’ and powers to do’; the dialectic between reflexive powers, action, reflective judgement and the growth of understanding and competence. Such understanding is, as Gadamer (1989) states, ‘selfunderstanding’. Keeping a journal produces a continuity of selfunderstanding and eventually it helps us to understand the complexity of our own creative processes. In it are preserved the continuity of personal growth and development. But what is the relatedness and difference between the process of the journal and the finished work, between the means and the end?

Zizek (1998) states that the end does not ‘realise itself via a detour: the End the subject has been pursuing throughout the process is effectively lost, since the actual End is precisely what agents caught up in the process experience’ (Zizek, 1998, p.127). In the journal the self is not expressed as a kind of static inner synthesis but is a continual process of construction and re-construction. Just as the End is not the one initially sketched out so neither is the subject the same ‘self’ as the one at the outset. Journal use goes beyond the expression of the self, that was an integral to Romanticism and modernism to the reflexive construction of the self. Self, in other words, is not seen as something just given as an unchanging inner synthesis but something that has to be routinely created and sustained in the reflexive activities of the individual. There is an urgent need, therefore, for teachers to develop a more sophisticated understanding of journal keeping.

References

Billington, M (1997) The Life and Work of Harold Pinter (London: Faber and Faber)

Bloom, H (1988) Poetic Origins and Final Phases. In Lodge, D. (Ed)

Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader. Pp.240—286 (London: Longman) Böttcher, K and Mitterzweil, J (1982)

Dichter als Maler: Deutschsprachige Schriftsteller als maler und Zeichner (Zürich: Buchclub Ex Libris Zürich)

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian Meditations. Translated from the French by R. Nice. (Stanford: California Univ. Press) Originally published in 1997.

Buzan, T. (1993). The Mind Map Book (Harmondsworth: Penguin)

Derrida, J. (1987) The Truth about Painting. Transl. from the French by G. Bennington and Mcleod. (Chicago. Chicago Univ. Press)

Dixon, P. (1971). Rhetoric (London: Methuen)

D’Arcy, P. (1989). Making,Shaping Meaning: Writing in the Context of the Capacity Based Approach to Learning (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann)

Dutton, D. and Krausz, M. (1981). The Concept of Creativity in Science and Art (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff)

Gadamer, H-G (1989) Truth and Method. Transl. from the German by J. Weinsheimer and D.G. Marshall (London. Sheed and Ward)

Galluzzi, P. (1996) Renaissance Engineers: From Brunellschi to Leonardo da Vinci. Translated from the Italian by J. Mandelbaum (Florence: Giunti)

Harre, R. (1983) Personal Being: A Theory for Individual Psychology (Oxford. Blackwell)

Harste, J. C. and Short, K. G. (1988). Creating Classrooms for Authors: The Reading Writing Connection (Portsmouth: Heinemann)

Heidegger, M. (1975). Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated from the German by A. Hofstadter (New York. Harper & Row)

Jarvis, P (ed) (2002). The Theory and Practice of Teaching (London. Kogan Page)

Kress, G. (1997) Before Writing: Re- Thinking the Paths to Literacy (London: Routledge)

Lawson, B. (1997). How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystified. 3rd ed. (Oxford: Architectural Press)

Pigrum, D. (2001). Transitional Drawing as a Tool for Generating, Developing and Modifying Ideas: Towards a Programme for Education. (unpublished Ph.D Thesis. University of Bath)

Ryle, G. (1979). On Thinking (Oxford.Blackwell)

Smith, F. (1982). Writing and the Writer (Oxford: Heinemann)

Wittgenstein, L. (1963). Philosophical investigations. Translated from the German by G. E. M. Anscombe. (Oxford: Blackwell)

Zavlovskaya, T. G. (1987). The Drawings of Pushkin (Moscow: Iskustvo) (Title translated freely from the Russian original).

Zizek, S.(1998) The Indivisible Remainder: An Essay on Schelling and Related Matters (London: Verso)