13 minute read

Lawmakers advance bill seeking $280 million to fund ‘innovative’ crime prevention programs

By Tim Walker Minnesota House Session Daily

“To Protect and Serve” is a common slogan for law enforcement agencies.

Advertisement

But “To Heal and Restore” should also be part of that equation, says Rep. Cedrick Frazier (DFL-New Hope).

He sponsors HF25, which would expand the role of law enforcement and the criminal justice system by funding more communitybased crime prevention services, such as victim services programs and juvenile diversion programs. It would also provide funding for social service workers to accompany police when they respond to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis.

The bill takes

“an innovative and multifaceted approach … for the reduction, intervention, and prevention of crime,” Frazier said. There is also money to increase funding for more traditional law enforcement roles that have been successful.

The House Public Safety Finance and Policy Committee approved the bill, as amended, Thursday and sent it to the House Ways and Means Committee.

The bill proposes a one-time appropriation of $280 million in fiscal year 2023:

$205 million to the O ce of Justice Programs: $150 million to fund grants to community groups for crime and violence prevention and intervention and $55 million to help local law enforcement agencies establish mental health crisis response teams; and

$75 million to the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension to continue to partner with local jurisdictions to investigate violent crimes.

In addition, the BCA would get $10 million in the 2024-25 biennium to expand the work of its Use of Force Investigations Unit. Although her work focuses on events after a crime has been committed, Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty said she recognizes the most effective way to deal with crime is to prevent it from happening in the first place.

“This bill represents a historic recognition that investing in prevention and intervention will help prevent harm and save lives,” she said.

Hennepin County Commissioner Irene Fernando said the county has seen great success in its recently established program to embed mental health workers with police officers responding to mental health calls.

“This is an important step to improve the response we give to people,” she said. “The collaboration between public safety and behavioral health builds capacity within the emergency response system to better manage mental healthrelated calls.”

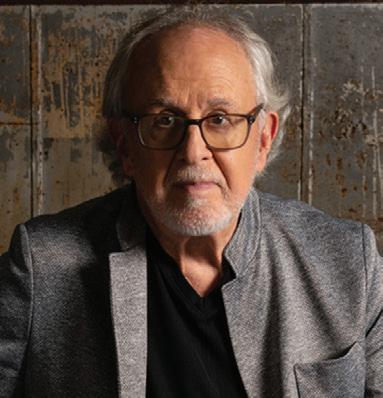

African American roots performances, the idea of democracy flows through this vernacular music. The idea is that the performance is part of a community. That communities are free to create together.”

Henry says that this shared creativity could be observed in Black ancestoral music, as well as in jazz music and even folk. But in today’s genres, Henry warns, with music evolving culturally and becoming more suited to global and predominately Western tastes, this creative, communal, and democratic aspect of music is diminishing rapidly.

“Music has become the realm of the virtuoso specialists, and we don’t feel free as individuals to participate and create as a community,” he says.

Henry also notes that while many spirituals today are sung, he has, over the years, found that they are often sung without understanding the historical context they were formed in.

He adds that if more singers and performers understood the history behind some of these spirituals, they would sing them more meaningfully.

“When I went to Cuba, I had the honor to work with this wonderful choir, one of the best choirs in the world. They were singing Negro spirituals. They sang beautifully and intricately well. And then, I just asked them, ‘Do you know a story of our people? Do you know a story of how these songs were resistant, coded messages, et cetera?’ And they did not know. They had no idea.” difficult for students to realize the full potential of their education between the threat of insurmountable student debt exacerbated by COVID19’s severe financial setbacks, along with a concerted effort to overturn affirmative action and turn back the clock on diversity and equal opportunity,” said Genevieve “Genzie” Bonadies Torres, associate director of the education opportunities project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “We urge the court to affirm President Biden’s debt relief plan, which would provide essential relief for Black and Brown borrowers — especially women of color — who are still recovering from the economic fallout disproportionately shouldered during the pandemic. The Lawyers’ Committee is committed to fighting for every student’s right to receive a quality education and achieve financial security, regardless of economic status, gender, or race.”

“All students deserve a fair shot at getting a quality education, regardless of their income, where they grew up, or their racial and ethnic background. However, while talent is everywhere,

Henry says following their new insight into the songs they were singing, they sang the same songs with more depth and were transformed in their performance. The Chicagobased jazz vocalist says through his music and the curriculum he developed, which focuses on teaching communities the importance of culture and collaboration, he intends to ensure that more people, old and young alike, learn about the historical significance of spirituals. He has written opportunity is not. Too many students of color must contend with systemic and interpersonal racism that detrimentally affects their educational opportunities,” said Michaele Turnage Young, senior counsel at the Legal Defense Fund (LDF). “Later this year, in lawsuits involving Harvard and UNC, the Supreme Court will decide whether colleges and universities can continue to consider race, as one of many factors, in admissions. It is important that colleges and universities continue to be allowed to consider the full context of applicants’ experiences, including the way that racism artificially depresses the prospects of many hardworking, talented, Black, Latinx, Native, and underserved Asian American students.”

“All students deserve safe, healthy, and inclusive school climates. Every student deserves the opportunity to attend positive school environments that support their rights, protect against harassment and discrimination, and ensure their health and safety,” said AJ Link, policy analyst at Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

“At IDRA, we know that culturally-sustaining schools are key to students’ success. Culturally-sustaining schools are places where every student feels welcome — no one is asked to check parts of their identity at the door; hundreds of songs, including ‘Africa Cries’, which he explained was inspired by a dream and had very few lyrics. The lyrics say, “How can we rejoice when she is in pain? Africa will live to rise again. While the world lives on and we deny, how can we be happy while she cries?”

He also recently released a Christmas album on CD.

When Henry isn’t writing songs for social change, he is educating others on the evolution of music through his program, which aims to give those interested in the everyone sees themselves and their communities reflected in the curriculum and instructional practices; diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are meaningful; and everyone feels safe,” said Morgan Craven, national director of policy, advocacy and community engagement at Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) “We know that these types of learning environments are beneficial for all students and adults in a school community, and we must challenge any efforts to undermine them.”

“We are entering year four of a pandemic that pressure-tested an early care and education system already in crisis, causing devastating results across the country for early educators and families alike. For the early care and education sector, the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare and exacerbated the deep inequities of an early care and education system that relies on families paying unaffordable sums, early educators being paid poverty level wages, and too many communities across the country lacking sufficient workforce or facilities to meet early care and education demands. These inequities disproportionately impact women and families of color. The pandemic has only brought more challenges, especially for women of color, who comprise a significant intersections between music and culture an overview of African American music from 1619 to the modern music we hear today.

Finally, when he isn’t educating, he manages a community garden affiliated with a church in Chicago that helps feed hundreds in that community weekly. To purchase his music, book him for a performance or learn more about the historical foundations of music and the links between the music we know today and the music of our African ancestors, be sure to visit his website at https://www.bruceahenry.com/ portion of the underpaid early care and education workforce and have the least access to affordable care for their children. In order to ensure that children and families have access to and are included in comprehensive, diverse, and high-quality early care and education settings, we seek policies that reflect our coalition’s Civil Rights Principles for Early Care and Education,” said Whitney Pesek, director of federal child care policy at the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC). “In 2023, NWLC, along with the coalition, continues to engage and educate diverse stakeholders and policymakers around these principles to protect civil rights and advance equity for children, families, staff, and providers.” fi

The Leadership Conference Education Fund builds public will for federal and state policies that promote and protect the civil and human rights of all persons in the United States. The Education Fund’s campaigns empower and mobilize advocates around the country to push for progressive change in the United States. It was founded in 1969 as the education and research arm of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. For more information on The Education Fund, visit civilrights. org/edfund/.

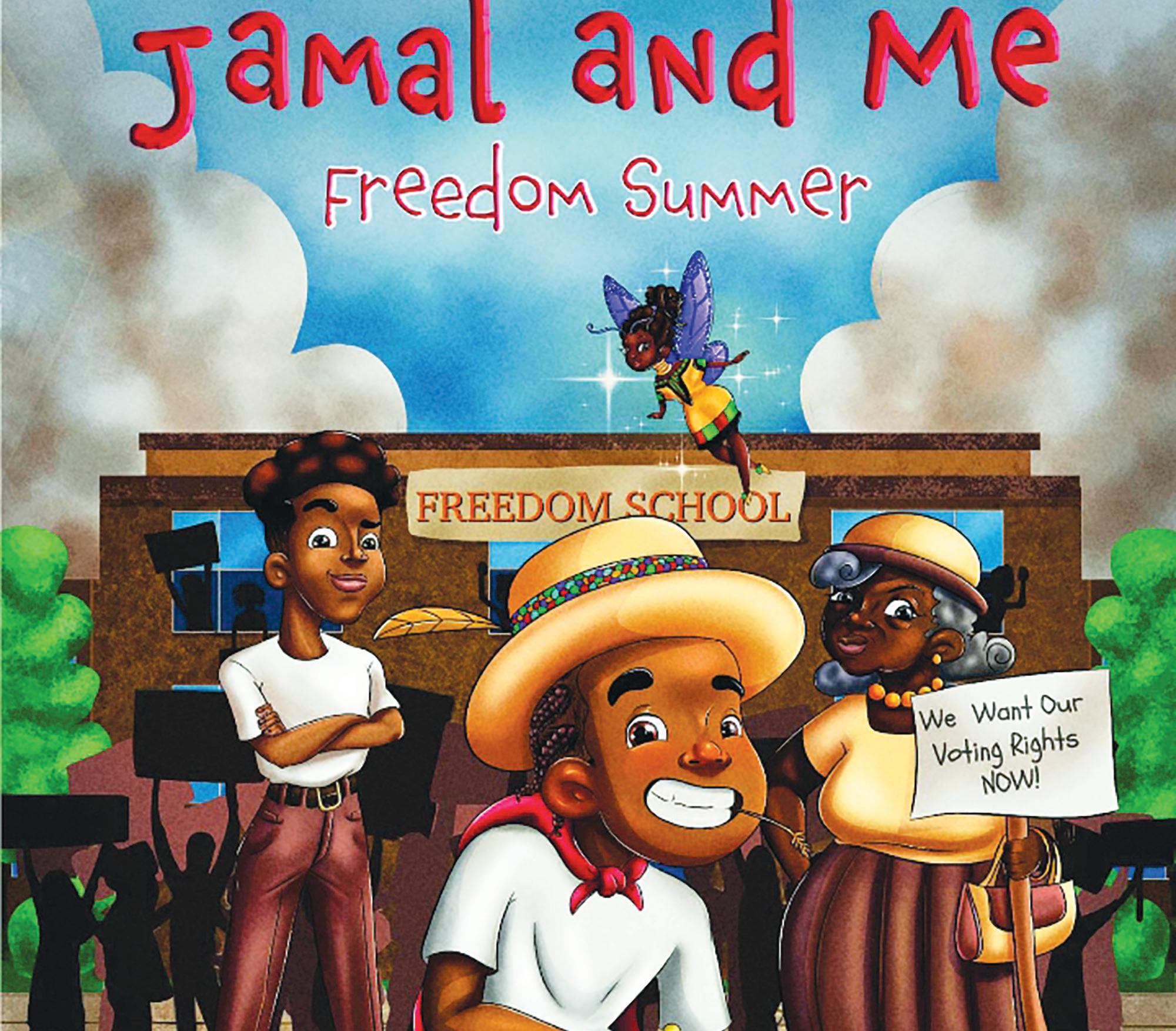

By: W.D. Foster-Graham Book Review Editor

By J. Darnell Johnson

Black is here, founded by Carter G. Woodson to honor the contributions we have made as African Americans in all areas of history. To kick it off, I am pleased to review J. Darnell Johnson’s work of historical fiction, Jamal and Me: Freedom Summer.

Johnson’s story is told through the lens of 11-year-old Jordan Washington. Jordan ran for sixth-grade student council president, with All-American girl Kamilla Payne as his opponent. Although his stump speech is heartfelt and substantial, he loses the election.

Meanwhile, his 9-yearold brother Jamal is excited because he has won the District 8 School of the Heart Jelly Bean Guessing Contest, qualifying him for the Region Two contest, something no Black person has achieved. Jamal has a gift—he doesn’t guess the number of jelly beans, he counts them, and he wins every time.

At the library, after Jordan registers Jamal for the contest, Jamal in engrossed in a book, The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer, checking it out along with other books on civil rights. This leads to a conversation with his Grandma Lynn about his greatgrandmother Mary Jo Washington, who was never registered to vote.

Later, on another summer night, Jamal and Jordan encounter a queen butterfly figure named Queen Azina, who has heard Jamal’s wish to meet his great-grandmother. She has the power to transport them back to the past. Their mission: to help her get registered to vote, but no one must know that they come from the future. One of the means of voter suppression back then was to have Blacks guess the number of jelly beans in a jar. She couldn’t pass that test, but it’s right up Jamal’s alley.

Through Queen Azina’s magic, Jordan, Jamal, and their dog Pharaoh are transported back to 1964 in the Mississippi Delta. They meet Fannie Lou Hamer and her family, attend the Freedom School, meet the civil rights workers who have put themselves on the line to increase Black voter registration in Mississippi. Will they find Mary Jo Washington? And when they do, will they succeed in getting her registered?

Johnson weaves a skillful, compelling story of ction, fact, and fantasy in addressing the issue of voter suppression through the eyes of Black youth. The blatant intimidation and scare tactics of whites in Mississippi, coupled with the insidious suppression tactics such as poll taxes and discriminatory literacy tests, are brought home to Jordan and Jamal in a new way. Being 12 at the time of Freedom Summer, I remember seeing the events unfold with my family through the evening news. With Johnson’s storytelling, the reader is there and living it. At the same time, he makes the story relatable to children by drawing parallels with today.

One passage in the story that resonated with me was how the belief that the Black vote didn’t matter was addressed. Indeed, if it didn’t, why were whites going to such lengths to keep Blacks from voting? The great strength, courage, and faith it took to persevere in the face of fear and danger for the basic right to vote speaks volumes.

Jamal and Me: Freedom Summer is available through Amazon and the Minnesota Black Authors Expo website.

Kudos to J. Darnell Johnson for his awesome story, and to Mychal Batson for his superb illustrations. In the words of Fannie Lou Hamer, “We want ours, and we want ours now.” That is as true today as it was then.

By Regi Taylor

This book review is considered ‘retrospective’ because I first read and offered insights on it exactly 5 years ago this month. However, recent incarceration statistics germane to this book’s premise which I uncovered while researching a related topic, suggests that The New Jim Crow, author, Stanford Law grad, Michelle Alexander’s conclusions were not only accurate, but prescient.

In the thirteen years since this book was first published the circumstances reported on by Ms. Alexander that formed the basis of her dire narrative have severely worsened. For African Americans, the rate of incarceration has increased, the total number imprisoned nationally has grown, and more women, men, and juveniles than ever are inmates. Most are functionally illiterate, portending continued ill-fated prospects for future employment, housing, education, public assistance, and voting, while the expanding gross labor exploitation prisoners are subjected to, with hundreds of thousands forced to work – literally – for pennies per hour or no pay at all for major corporations.

Consider this contemporary data:

African Americans are 13% of the U.S. population and 38% of America’s Incarcerated

The rate of incarceration for Black vs white Americans is 2,306 per 100,00 vs. 450 per 100,000, respectively

Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at nearly 5 times the rate of white Americans.

Nationally, one in 81 Black adults in the U.S. is serving time in a state prison

Estimates are that 3 % of the total U.S. adult population and 15 % of the African American adult male population have been to prison

People with felony convictions account for 8 % of all U.S. adults and 33 % of the African American adult male population

1 in 9 Black children have a parent in prison, compared to only 1 in 57 white children

Although only 13% of America’s population is African American, 40% of incarcerated parents are Black

Black women are 13% of the country, 30% of the women’s prison population, and 44% of women in jails

Forty-one percent of incarcerated youths are Black The context provided by these statistics will inform your perspective of my analysis of The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander:

Two-hundred years ago there was a 10-year-old Caucasian boy from New York City, Thomas D. Rice, whose starry-eyed dream was to get curtain calls on Broadway as an actor. Within 20 years he’d outgrown Broadway and regularly filled the concert halls of London playing his signature ‘caricature’, that lazy, lying, shiftless, dimwitted minstrel in blackface, Jim Crow.

Rice could never have fathomed that two centuries hence an African American female attorney and scholar, Michelle Alexander, would pen a groundbreaking tome about the conditions of slaves’ future offspring, that for the second time since the Civil War, are being demoralized and indentured under an Apartheid system once again known as Jim Crow.

The New Jim Crow is a remarkable book. While it was originally published in 2010 and received numerous accolades it was recently in the news when prisons in New Jersey and North Carolina tried, and failed, to get it banned. It is a scholarly work written in a conversational style without sacrificing the serious tone of the subject matter which commands a thorough academic analysis conducted with meticulous documentation.

This book is also a peek into one African American woman’s personal journey as she discovered and came to terms with a truth that she was not fully prepared to confront. Not only does Alexander appear to struggle with the nature, scope, sophistication, and power of the mass incarceration machine in America that is relegating millions of Black men to an inferior ‘citizenship’ status not seen for over half a century, she apologizes for being right. In her book’s introduction Alexander recalls an insightful comment made by an associate who followed up the comment with a nervous laugh as if she weren’t quite sure she wanted to believe what she’d just said. Some of Alexander’s pronouncements seem like they might be followed by a similar, inaudible laugh of her own. Like the Charleton Heston character in the movie, Soylent Green, who bellows in terror, “Soylent Green is people!” Her distress is palpable.

The nearly 20page introduction to “The New Jim Crow” comprehensively lays the foundation for logical persuasive arguments, painstaking methodology, and prefaces all the books chapters, providing signposts that makes for a read that lets you know where you’re headed, with narrative that continues to enlighten and enthrall.

Michelle Alexander’s premise: while some of us were celebrating hard fought victories from the Civil Rights era, and diabolical machinations behind the scenes working to reassert mass control and disenfranchisement over African Americans, and who knows to what eventual end.

In the 20 years from 1980 to 2000 the U.S. prison population swelled nearly 6600%, from 350,000 to 2.3 million. There are currently nearly 1 million African Americans behind bars in America. Not even our Black president saw this coming, nor could he stop it. “The New Jim Crow” is thoughtful, compelling, and farsighted. It should be required reading for all American students, but especially African Americans. Alexander did point out that her topic was narrow by design compared to the potential to expand into related areas of consideration. However, there is a natural companion piece to “The New Jim Crow” story that I am disappointed was not mentioned at all in this book.

A significant aspect of the “new” Jim Crow mass incarceration experience for affected inmates is tantamount to the new slavery as well, where the incarcerated are leased for labor – in six southern states for $0 pay – to a who’s who of mostly Fortune 500 companies that exploit them. Millions of Black fathers, sons, uncles, and brothers have the dubious distinction of simultaneously experiencing slavery and Jim Crow in 2018 –with no end in sight. “The New Jim Crow” should at least have alluded to this. The range of prisoner ‘pay’ among all 50 states is $0.14 to $0.63 per hour. Perhaps Ms. Alexander might expound on the topic of The New Slavery in a sequel.