9 minute read

John Register [1939-1996] | A Print Retrospective

from #EssentialArt

A MODERNISM INC. #EssentialArt ONLINE EXHIBITION

April 17 - May 31, 2020

Winston CONRAD, "John Register," 1986, color photograph 12 5/8 x 19 1/4 inches

This exhibition of prints by John Register marks the first in a series of online #EssentialArt exhibitions while Modernism remains closed due to the current public health circumstances.

At a time when much of the American population is practicing self-isolation, with retail stores, cafes, transit centers, and restaurants empty and shuttered, John Register’s work resonates more than ever.

Introduction and Excerpts from "John Register: Persistent Observer"

By Barnaby Conrad III, 1998

The paintings of John Register (1939-1996) chronicle a search for overlooked beauty in unpeopled places. As a record of America’s depersonalized landscapes, his paintings of empty coffee shops in Los Angeles, old hotels in Chicago and bus stations in the Southwestern desert celebrate sunlight, but also a haunting stillness tinged with regret and hope.

"Man Seated in Restaurant," 1987, oil on canvas, 17 3/4 x 17 3/4 inches

"Restaurant," 1990, etching, Edition: 19, image: 6 x 6 inches, sheet: 15 x 11 inches

Though he called himself a realist, Register filtered the observed world through a tightly focused emotional lens. Often starting with snapshots of his subject, the artist absorbed and dramatically distilled early sketches until the finished painting appeared weeks or even years later bearing little resemblance to the original scene.

His approach to painting is echoed in 20th century philosopher E.H. Gombrich’s statement that, “There is no neutral naturalism…All art originated in the human mind, in our reactions to the world rather than in the invisible world itself.”

"John Register" by Barnaby Conrad III, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1989, featuring: "Desert Restaurant," 1986, oil on canvas, 50 x 70 inches

"Restaurant Overlooking the Pacific," 1990, color lithograph; Edition: 6, image: 15 1/2 x 22 inches, sheet: 22 x 27 1/2 inches

In his last decade, many of Register’s images came from the streets of Los Angeles, a city to him that epitomized the alienation of American life. “When I drive around L.A.,” he said in 1989, “I look for an offbeat beauty. I don’t know what I’m looking for until I find it. There are things so ugly that I can’t paint them. Sometimes I get depressed by that city, and by other cities I visit. But I like the patina of things that have been battered by life.”

A pesistent observer, Register claimed these places not just as American scenes but as expressions of a philosophical inner landscape. How much of that internal terrain he chose to reveal differed from painting to painting. If some pictures appear to be lonely or beautiful while others seem banal or startling, it is not by accident. Register was both attracted to and repelled by the architectural structures he found around him, and the pictures varied according to his health and emotional state.

"Venetian Light," 1990, silkscreen & lithograph, Edition: 85, image: 43 x 36 inches, sheet: 50 x 42 inches

Register came to art late in life, and his journey was an unusual one. Along the way he became a race car driver, top advertising art director, photographer, tennis fanatic, competitive chess player, compulsive letter writer and reader, ice boat racer, backpacker, fisherman, surfer and family man. During the last 16 years of his life he battled life-threatening illness and underwent grueling medical therapies. His struggle to stay alive gave him a sense of urgency, and drove him to make paintings that were rich with meaning and remarkably focused.

Though the West Coast informed Register’s work, it would be an error to view him simply as a regionalist. As the late novelist and travel essayist Shiva Naipaul wrote in 1980, “California became, as it had to, the New World’s New World, its last repository of hope. In California you come face to face with the Pacific and yourself. There is nowhere else to go.” Register’s painted vision of California reminds us that the state anchors the western edge of the continent, a final, grand showcase for the American Dream. The artist was well aware of this, and wrote in 1989, “I feel the pressure of Des Moines, Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore pushing behind me as I look out to sea. The teeming welter of humanity pushing.” While many of his images came from Los Angeles, his search for material took him all over the country, from the Great Plains to New York City.

"Dining Car," 1977-82, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 45 inches

"Train Compartment," 1989, lithograph & pencil, Edition: 100, image: 6 x 3 3/4 inches, sheet: 11 x 8 1/2 inches

Why did he choose to paint dingy restaurants and lowly cafes? “They are something we experience universally, a kind of common denominator of interior space,” Register once said. “If I were to do my own house it would be too specific and not something that everybody can experience. But a café, hotel room or bus station—these are places we have all been before, places we can all relate to.”

The artist deliberately rejected obvious beauty to seek out another beyond the subject matter. “It’s not beautiful furniture, it’s all very ordinary,” he once said. “It’s as ordinary a chair as I could find. It’s as ordinary a table as I could find. It’s not that the ordinary chair is beautiful, but that in its ordinariness it becomes the essence of a chair, or the essence of a table.”

Register’s art ventured beyond mere representation to conjure a metaphysical resonance from the commonplace. Viewed as examples of realism, these paintings are windows on the late 20th century. Received as the work of a philosophical artist, John Register’s paintings ask us to contemplate the recent past, the fleeting present, and the unknown future.

"Train Compartment," 1989, lithograph & pencil, Edition: 100, image: 6 x 3 3/4 inches, sheet: 11 x 8 1/2 inches

"Wasteland Hotel," 1990, etching, Edition: 100, image: 6 x 6 inches, sheet: 11 x 8 1/2 inches

"Wasteland Hotel," 1990, silkscreen, Edition: 85, image: 33 1/2 x 48 1/2 inches, sheet: 42 1/2 x 56 1/2 inches

Cover of "Prologue to Ask the Dust," Special Edition by John FANTE with illustrations by John REGISTER, 1990, Modernism, Magnolia Editions, Okeanos Press, Edition: 75

Plate I from "Prologue to Ask the Dust," by John FANTE, 1990, unbound etching, image: 4 7/8 x 4 7/8 inches, sheet: 13 1/4 x 9 7/8 inches

Plate II from "Prologue to Ask the Dust," by John FANTE, 1990, unbound etching, image: 4 7/8 x 4 7/8 inches, sheet: 13 1/4 x 9 7/8 inches

"Hollywood," 1989, silkscreen, Edition: 75, image: 14 3/8 x 11 1/4 inches, sheet: 21 x 17 inches

This work was created by John REGISTER for the cover of Charles BUKOWSKI’s “Hollywood” book.

"Oak Chair," 1990, hand-colored etching, Edition: 11, image: 8 x 8 inches, sheet: 22 x 15 inches

"Oak Chair," 1990, etching, Edition: 30, image: 8 x 8 inches, sheet: 22 x 15 inches

"Cadillac Hotel," 1990, etching, Edition: 30, image: 15 1/2 x 19 3/4 inches, sheet: 22 x 30 inches

Cover of "John Register: Persistent Observer" by Barnaby Conrad III, San Jose Museum of Art, Woodford Press, 1998, featuring: Waiting Room, 1982, oil on canvas, 50 x 61 inches

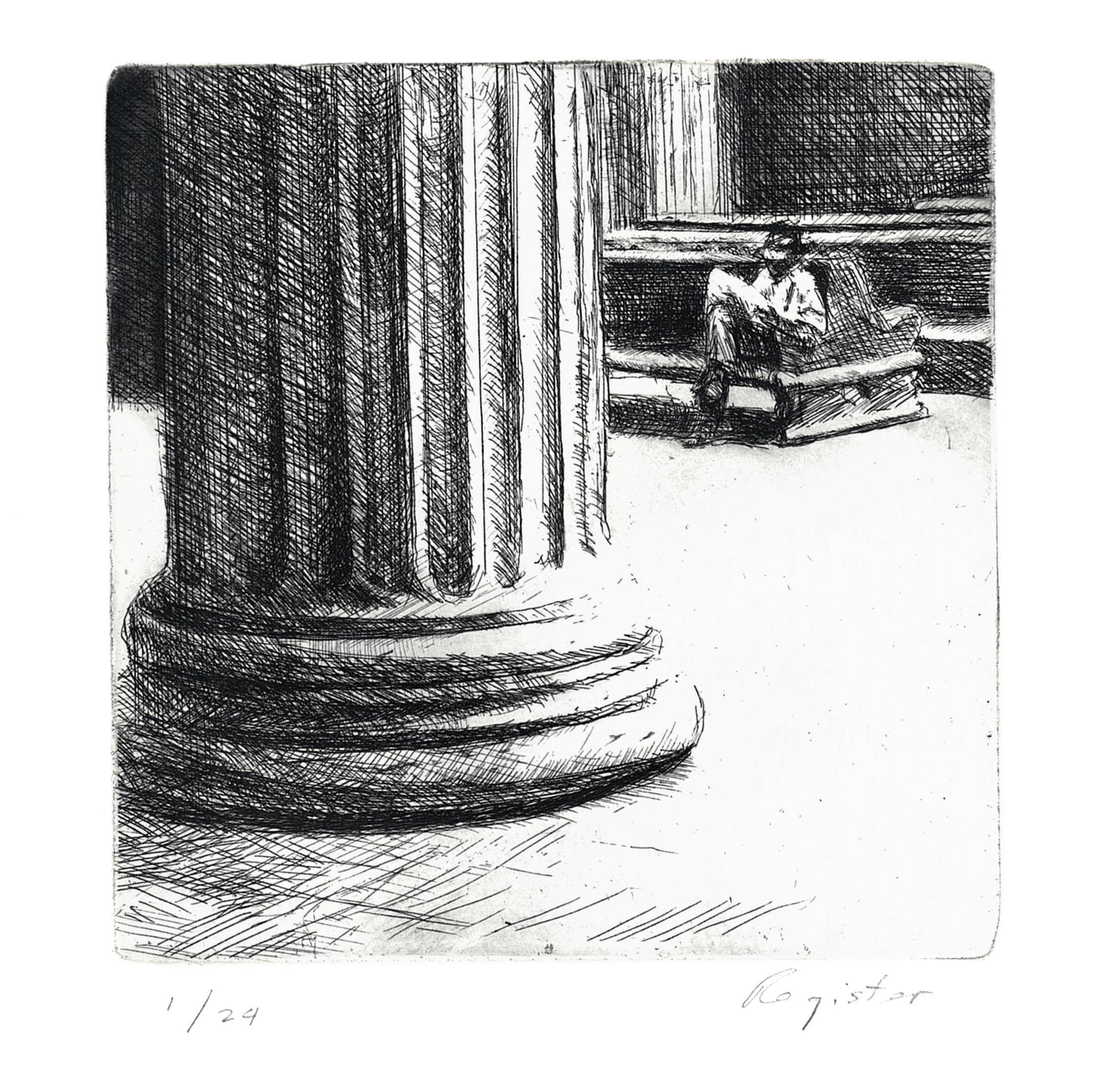

"Waiting Room," 1990, etching, Edition: 40, image: 7 3/4 x 7 3/4 inches, sheet: 22 1/2 x 15 inches

Peter REGISTER, "John Register with Telephone Booth Painting," 1994, gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 inches

"Waiting Room for the Beyond," 1988, silkscreen, Edition: 85, image: 35 x 35 inches, sheet: 41 x 41 inches

"Waiting at the Terminal (Airport)," 1990-91, oil on canvas, 70 x 49 inches

Biographical Notes

John Register [1939 - 1996] was born in New York City on February 1, 1939, but was raised by his mother in Santa Monica, California. He spent most of his adult life working between California and the East Coast. He received his B.A. in Literature from UC Berkeley in 1961, and continued his education in commercial art at the California School of Fine Arts, the Art Center School of Design in Los Angeles (where he met his wife Cathy while enrolled in a photography class), and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

At the age of 33, Register abruptly abandoned commercial art to take up painting, punctuated by long-distance running and other sports while in good health. Uninterested in cultivating art-world celebrity, Register preferred solo time in his studio. He maintained a regular studio practice despite several cross-country moves with his family and frequent bouts of ill health as he fought kidney disease and several cancers. A man of profound determination, he explained: “I’d paint some of my best pictures when I wasn’t feeling well… When you have a limited amount of energy you tend not to overwork a painting. You are more lucid about what you have to say and less concerned about the finish”. He died, surrounded by his family, at the age of 57 on April 9, 1996 in Malibu, CA

Register’s first solo exhibition was with David Stuart Gallery in Los Angeles in 1975. Since, his work has been exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions in museums and galleries across the country, including a major, travelling retrospective at the San Jose Museum of Art in 1999 with an accompanying monograph. Register first exhibited with Modernism in 1982, with eight subsequent solo exhibitions before his death. His work has also been included in fifteen group exhibitions at Modernism.

In 1986 Register was honored with a Francis J. Greenberger award. His work is held in the collections of numerous major institutions around the world.

"Studio Still Life," 1995, oil on canvas, 22 x 28 inches

"Red Booths," 1986, silkscreen, Edition: 85, image: 28 x 43 inches, sheet: 33 1/2 x 48 inches

Featured on cover