5 minute read

Bill Hodges Gallery

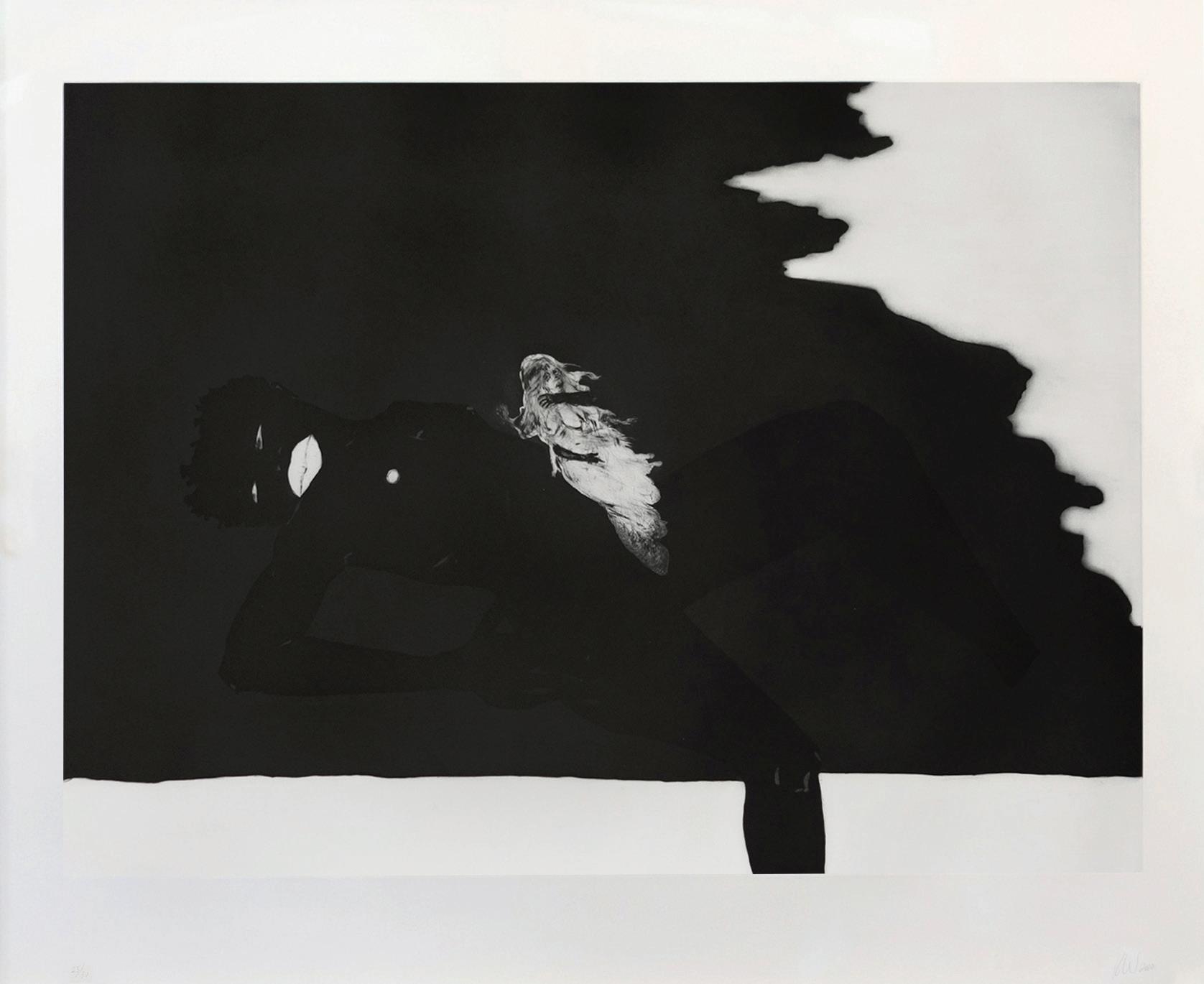

Kara Walker (1969 - )

buoy, 2010

Etchiung with Aquatint, Sugar-lift, Spit-bite and Dry-point, Painted on Hahnemuhle Copperplate Bright White 300gm paper

Edition of 30

Image: 23 ¾ x 32 1/4 in. (60.3 x 81.9 cm)

Paper: 30 1/4 x 36 1/4 in. (76.8 x 92.1 cm)

Signed and Dated, Lower Right: KW 2010

Numbered, Lower Left: 23/30

Ascene of companions in comfortable contemplation, Charles Sebree's Two Figures in an Alleyway is an endearing portrait whose compotion is balanced by a careful attenuation to light, shadow, and dimension. The figures depicted, whose sloping silhouettes anchor the work's quiet rhythm, are dressed in everyday attire. One peering curiously, the other with a downcast gaze, the solidarity invoked within the layer of paint on masonite distinguishes this composition as a classic work of Sebree's ouvre.

Charles Sebree (1914 - 1985)

Two Figures in an Alleyway, 1938 Oil on Masonite

20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 61 cm)

Signed, Lower Left: Sebree

Elizabeth Catlett's sculpture, The Family depicts an African American father, mother, and child standing and embracing. In bronze with brown patina, the lines of The Family follow the soft curve of her fine carving techniques, making the figure feel at once monumental and timeless. From the portrayal of this heartwarming American family, the artist would continue to find imagery to fuel a revolution, reminding us of the role that art can play in the fight for social justice. As Catlett once proclaimed, “We have to create an art for liberation and for life."

Bill Hodges Gallery

Elizabeth Catlett (1915 - 2012)

The Family, 2002

Cast Bronze with Brown Patina on Wooden Base 15 ⅛ x 5 1/4 x 5 1/2 in. (38.4 x 13.3 x 14 cm)

Initialed on the Back: E. C.

Known as the earliest documented professional African American artist in the United States, Joshua Johnson (ca.1763 - ca.1824) was active in Baltimore and profited by painting Baltimore's rising middle class of merchants, importers and their families, during a time when portraits are deemed as an symbol of superiority. The two portraits, Baltimore Shipowner and Baltimore Shipowner’s Wife, displayed side-by-side above, as the way they are supposed to be hanged, would be an exceptional demonstration of the artist’s style.

Typical of Johnson’s work during his most active years, the deep green spandrels encircle the figures, who are meticulously limned on a black background. Johnson’s naïve art, which means art made by artists who are never formally trained, merges the humanistic portrayal of figures in Renaissance art into the framework of Medieval art. Two sitters pose stiffly in a three-quarter view, sharing formulaic facial structures, whereas the outlines are delicately rendered. With the translucent glazes covered on the thinly painted surface, the subtle skin tone is lightened up, and the textures of the luxurious fabric such as the cravat of the shipowner and the frill on the hood of his wife are enhanced.

Hale Woodruff’s Torso, a dynamic crayon and charcoal on paper work, features the hazy, segmented form of a human figure. With line making that utilizes both the negative space of the paper and striking, demonstrative strokes of charcoal, Woodruff positions the center of the figure as a strong anchor for the surrounding liveliness of the composition. Balancing both a sense of horizontality and verticality in the form’s shape, this monochromatic work appears as a near-abstraction of the artist’s recognizably bold, muscular early style.

Hale Woodruff (1900 - 1980)

Torso, ca. 1960

Crayon and Charcoal on Paper

27 1/2 x 20 1/4 in. (69.9 x 51.4 cm)

Signed, Lower Left: H. Woodruffverse

As one of America’s most brilliant and dynamic woman painters, Marion Greenwood (1909 - 1970) is most well known for her murals, which makes this intimate work on paper, Mother and Child (Study), a rarely-seen piece. A woman whose gaze is framed by soft, sweeping gestures of charcoal cradles the gentle silhouette of her child in this charcoal drawing. Produced during a 1951 trip to Haiti, this tender vignette is the picture of maternal care, a sensitive depiction of family nurturing. With dynamic line-making accented by shades of shadow, this work by Marion Greenwood exemplifies the artist's intentionality and deliberation with regard to her celebrated portraits. Using rough yet sweeping strokes, Greenwood documents the everyday experience of life with a spirit of liveliness and dimension that is felt even in this monochromatic study.

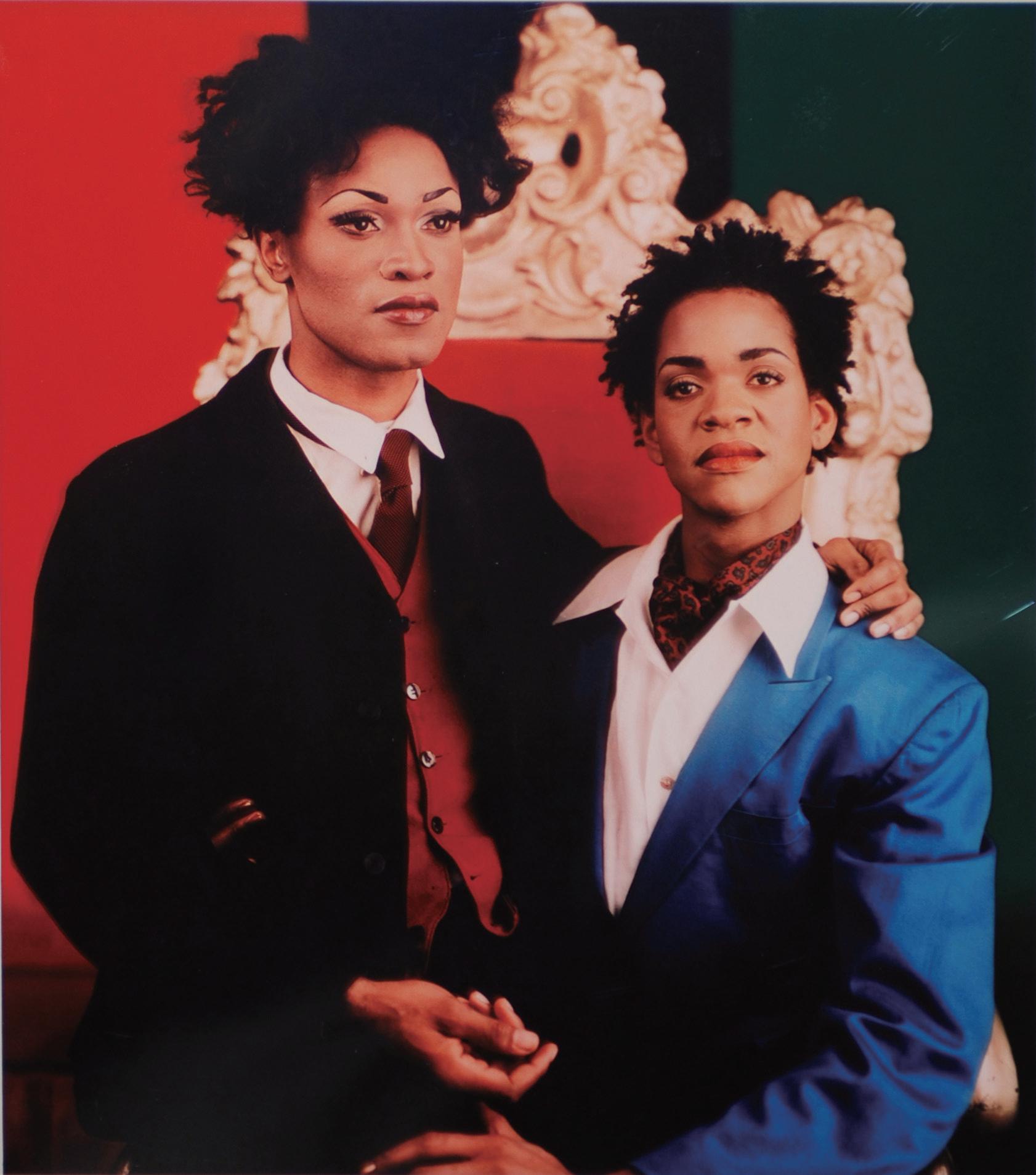

Lyle Ashton Harris' Sisterhood is a gentle, yet powerful composition of dignified care. A portrait of two figures whose attire and visage blends masculine and feminine archetypes , this photograph exudes a sense of regal dignification. With the use of red, gren, and black, Harris engages with notions of peoplehood, Black nationhood, and gender in this evocative, beautiful image.

Curving into the shape of his song, the performer figured in Benny Andrews' Violinist is a delightful composition. A work that exemplifies the artist's signature thinlined drawing style, this ink on paper depiction of musicality is a monochromatic delight. A visual characterization of the crooning, sweeping soprano sound of the instrument, Andrews' Violinist is a pleasant rendering of melodic art.

Chester Higgins' Brazilian Ochun is a striking, beautiful composition of spiritual regality. The image shown here is featured on the cover of his book, Feeling the Spirit. Photographed in 1989, the woman represents and celebrates the Ochun goddess. A deity of love and beauty originally worshiped by the Yoruba people of Africa that made its way into the religions of Latin American countries, such as Brazil. The title indicates the woman is a native of Brazil and thereby ties Latin America to the African Diaspora through religion.

Brazilian Ochun, 1989

Printed 1996

Archival Gelatin Silver Print

Image: 19 x 12 7/8 in. (50.17 x 32.7 cm)

Paper: 19 7/8 x 15 7/8 in. (50.48 x 40.32 cm)

Signed and Chopped logo (emblem) on Reverse

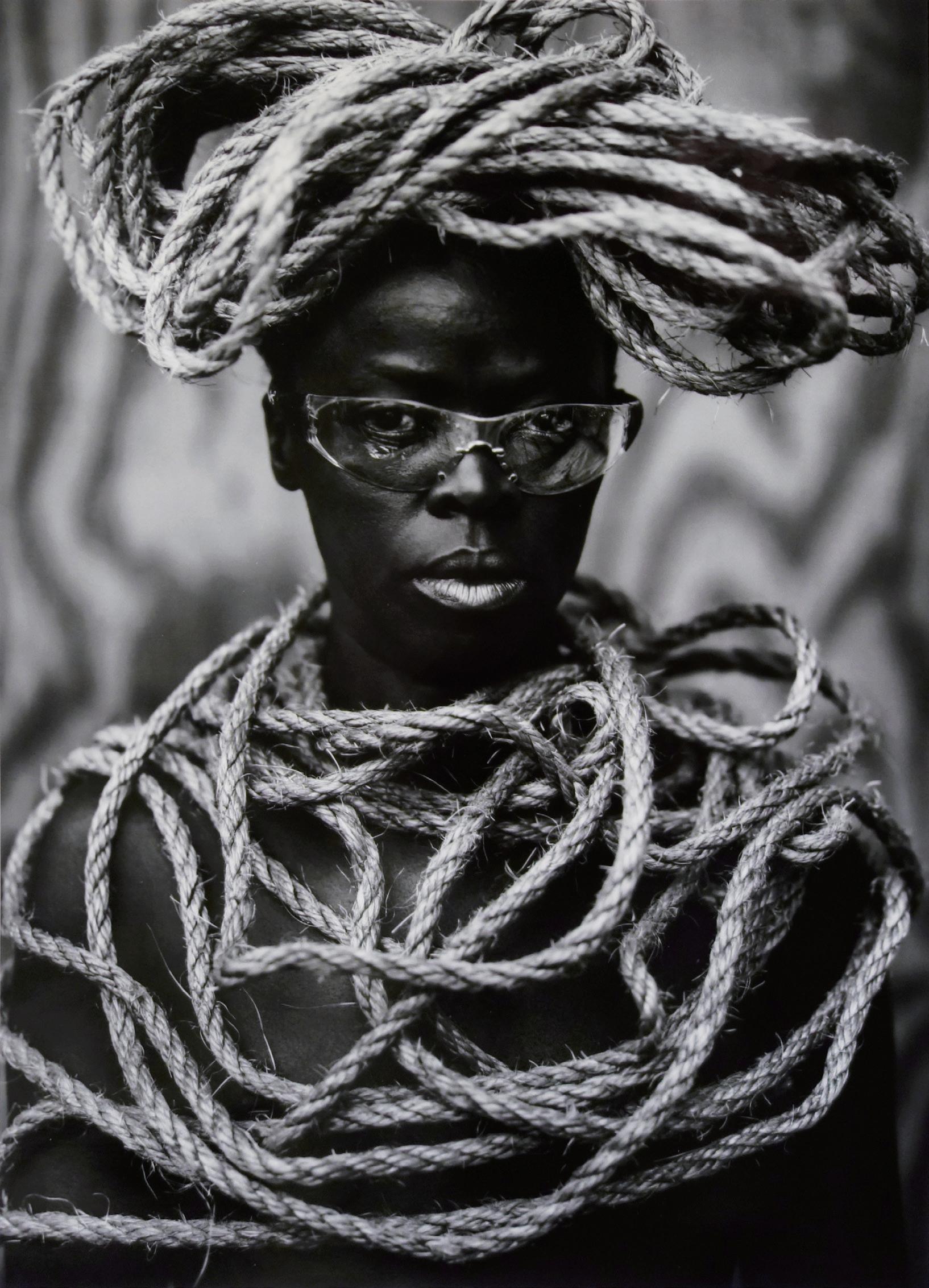

Ropes that could bind and constrict are seen instead winding gracefully around the proud neck of a black figure in Zanele Muholi's gelatin silver print MaID, Philadelphia. n this work, Muholi turns the camera to themselves. A part of the series Somnyama Ngonyama (meaning ‘Hail, the Dark Lioness’), MaID, Philadelphia, a self-portrait, aims at the politics of race in the photographic archive. A composition wherein the subject's unwavering resolute gaze is the focal point, Muholi portrays themselves in a highlystylized fashion. The image maintains a softness despite the visual confrontation of the gaze; as the figure's sable visage anchors the rhythm of the work. In MaID, Philadelphia and related works, Muholi asserts the stakes of racial representation and expression, the conventions of which they feel "[are] continuously performed by the privileged others”. With their camera, Muholi questions the current hierarchy of the art world and fills the vacancy in the related field of documentary photography.

Jean-Baptiste

Carpeaux’s Pourquoi Naître

Esclave (translated: Why Born a Slave”) is a terracotta bust depicting an enslaved woman with distinctly African features. Constrained by ropes that bind her chest and arms, the figure leans forward, gazing defiantly over her shoulder. The composition of this bust was modeled in 1868 and would later be carved into marble in 1873, though the abolition of slavery in the French colonies occurred over twenty years prior (1848). While Carpeaux’s inscription “Pourquoi naître esclave?" indicates the work’s abolitionist intent, the bust’s rendering of Black humanity as still confined within the bounds of enslavement perpetuated traditional Western ideologies that normalized imagery of the subjugation of African peoples. As a result, this important work embodies the complex crossroads of colonial exploitation, racial fascination, and emancipation.