3 minute read

When The Book Is NOT a Picture in Your Head

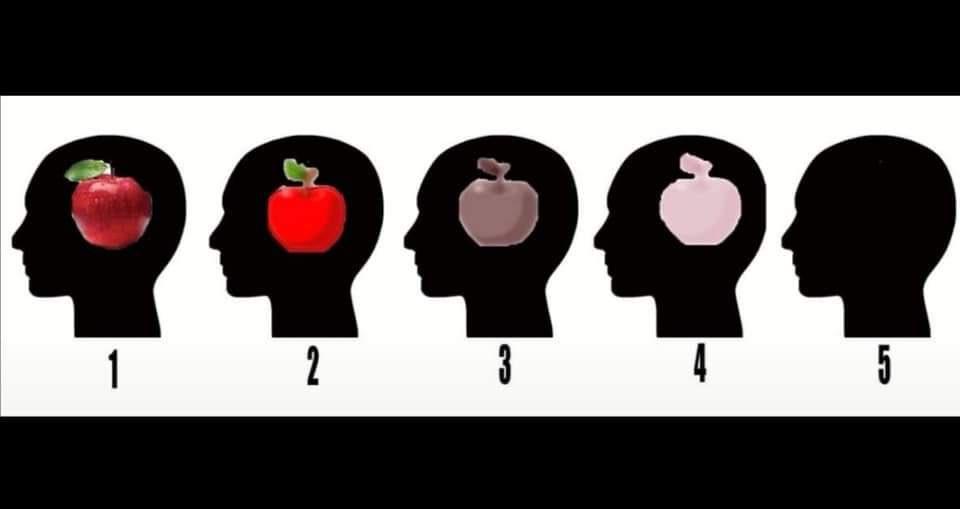

A year or so ago, I came across a social media post about a study by Adam Zeman, a professor of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, concerning something called “aphantasia”, where a small percentage of the population cannot visualize anything in their minds.

The common example is an apple presented in various levels of detail, from a "1" at completely vague up to a "5" where the apple was 3D, in vivid detail. The post mentioned some people, when asked to picture an apple in their head, saw the 3D version, and others were at the other end where they could barely picture anything, with many people at different levels in between.

Advertisement

This post surprised me and generated quite a bit of discussion amongst family and fellow reviewers, as we realized some of us didn’t actually picture a movie in our heads when we were reading. In fact, I was one of those who leaned toward the more vague to nothing. While this inability to visualize in no way prevents a person from being creative, it does affect how the same book is enjoyed.

I Higured out really quickly as a child that I read faster than my peers and had an excellent memory for content. I can also recall the story of a book I’ve read before when presented with that book’s cover years later. However, if asked to picture the book cover of a book I just read, I get nothing. At best, it’s a fuzzy Hlash of memory, but I can’t actually picture it.

Instead, when I read, I mentally assign a voice to each character, and tend to skim long descriptions. (I’m looking at you “The Lord of the Rings”.) Thus, most audiobooks are irritating to my ears as the voice used clashes with my mental one. Further descriptions of something like rain sparks the “sound” in my head, but no image or smell or feel. My sister, on the other hand, reads the same books but is able to fully “see”, “hear”, and even “smell” the rain described in her mind. When

By: Sarah McEachron

discussing a book we’ve both enjoyed, I’ve often found that what we noticed and remembered from the story also differs.

For me, the conversations, the emotions conveyed, and the plot stick with me and make me want to read more, whereas my sister notices that character A was standing by the kitchen counter in a pink silk blouse and faded blue jeans, and is now talking to Character B on the living room couch while wearing yoga pants, but there was no mention of Character A moving toward Character B or changing clothes. The image in her head is disrupted by the lack of description. However, I will not notice this missing description as long as the conversation itself is smooth.

The ability to visualize based on description in books also affects whether a person will like the movie based on their favorite books. When the Hirst "Harry Potter" Hilm came out, there was a great deal of discussion about the placement of Harry’s scar. Some fans were adamant that Harry’s scar should be in the middle of his forehead, and others didn’t mind that slightly offcentered placement. To the readers who could visualize, the Hilm director’s decision was jarring to their own mental image. Whereas to those of us who can’t visualize, the only concern was that the famous scar was present.

How does this matter? Well, to some people it doesn’t at all. Some people will enjoy reading and writing no matter how much description is used. Others will need a certain level of description or the book will be dropped part-way. The only way to combat this is with a balance of description and conversation, detail, and emotion. This can be trickier with certain genres, such as Fantasy or Sci-Fi, which rely heavily on made-up beings or technology that doesn’t exist, but a solid book cover or inserted image or two can combat this. Fortunately, there are more and more ways to tell a story. Besides Hilm, webcomics are becoming increasingly popular and provide the description in their provided art. Audiobooks, like those made by “Graphic Audio”, tell stories with added sound effects and a cast of narrators, reminiscent of old radio programs from the early to mid-1900s. Authors of all kinds and in all genres have different styles, some of which will reach those who visualize perfectly, and those of us who can’t picture a thing.

Regardless of whether you can actually see that apple in your head or not, everyone can enjoy a good book, but it doesn’t hurt to know how well you and your friends can visualize and think about what form of story will appeal to someone who hasn’t been willing to read your favorite book – until now.