4 minute read

A confluence of two great rivers

from 2010-02 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

Multicultural Affairs and Settlement Services.

It is often said that for a Hindu, life is incomplete without bathing in the Ganga (or Ganges) river, at least once. It is sacred, and people travel from distant places to immerse the ashes of loved ones past in the waters of the 2510km long Ganga; this is believed to send the ashes to heaven. The act of bathing in the river on certain occasions is also said to cause the forgiveness of sins and helps attain salvation. Drinking water from the Ganga with one’s last breath is said to take the soul to heaven. In fact, the simple act of having a vial of water from the Holy Ganga in one’s home is said to be auspicious.

Closer to home rests the Murray River, forming a 2375km long natural barrier between New South Wales and Victoria. It is often referred to as the “Mighty Murray”, and has significant cultural relevance to Indigenous Australians. According to the peoples of Lake Alexandrina, the Murray was created by the Great Ancestor, Ngurunderi, as he pursued Pondi, the Murray Cod, with the help of his two wives. While some variations of the story exist, it is agreed that the Murray is especially important in Indigenous Australian mythology.

However, it is easy for us to forget just how much has changed about these great rivers over time.

Previously “Mighty”, the Murray now receives just 36% of its natural flow, while the Ganga, once considered the epitome of purity and divinity, lives a polluted and decrepit life as a result of the relentless abuse shown towards it by the very people that worship it.

On Saturday, the 13th of February, Valentine’s Day fell a day early as several groups and communities combined to perform the dance-drama Ha’Murray Ganga at the Parramatta Riverside Theatre, sharing their love for the Murray and Ganga river systems. Director Kakoli Mukherjee of the Bharatiya Sangeet Academy spent over two years preparing for the program, saying “I’m not a writer; I’m not a poet. I’m a singer. To write about this I needed to read, I needed to look and I needed help from people.” However, the vision and idea lay with Ms Mukherjee from the start.

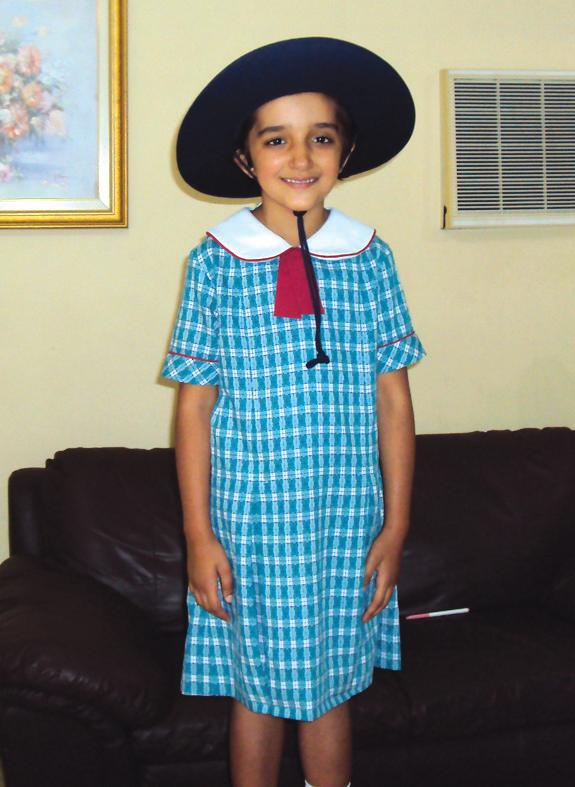

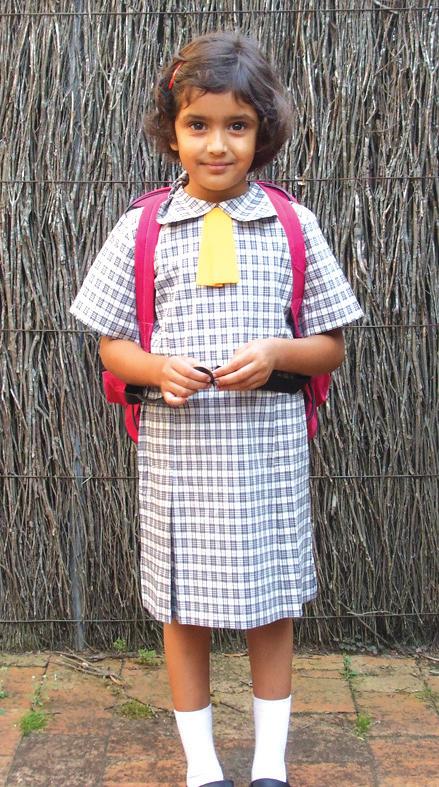

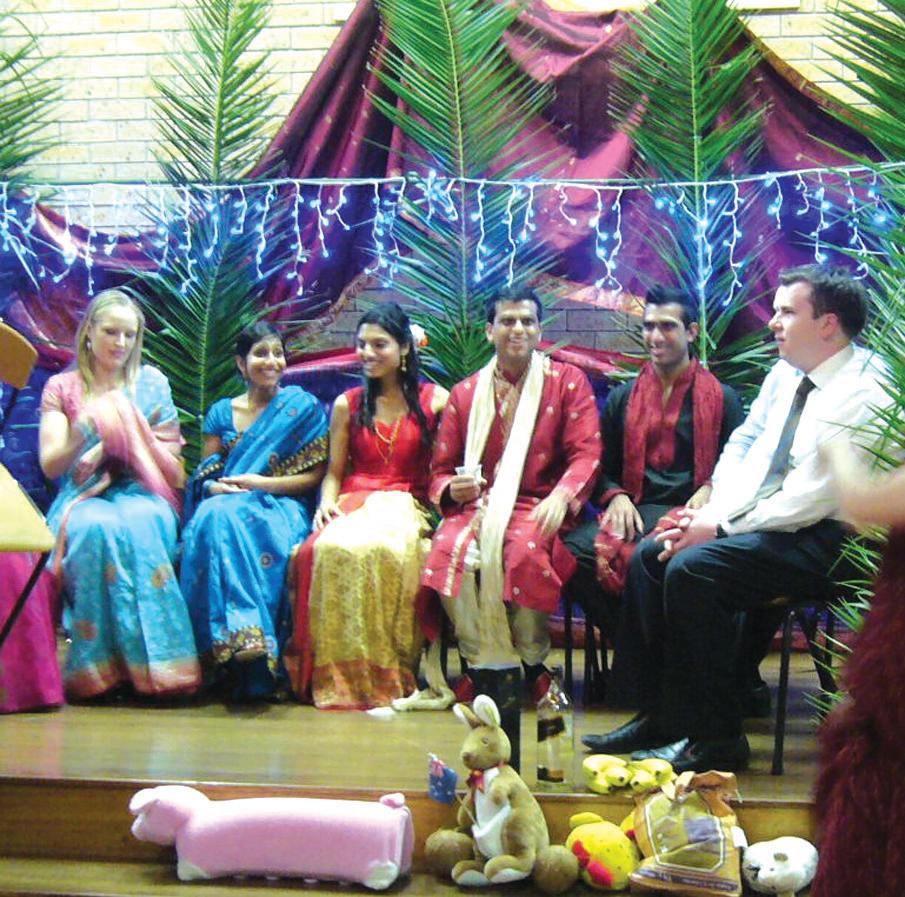

And what a vision it was. From the very opening segment, a spiritual mood was evoked – a traditional (albeit electronic) lighting of diyas or pradeeps was performed by Julie Owens MP, a proud supporter of the campaign. A small glimpse of the amazing colour and splendour of traditional Indian costumes to follow throughout the night was shown through beautiful little girls presenting garlands to Ms Owens and Mr Laurie Ferguson, Parliamentary Secretary for

This opening was followed by the Indigenous Australian welcome and land acknowledgement ceremony, performed by the Koomurri Dance Troupe. The sounds of the yidaki, a variation of the didgeridoo, resonated throughout the hall, with “Uncle” Greg Simms’ welcome heralding the opening scene of the dance/drama; a dance exploring Ngurunderi’s pursuit.

If there was one thing that stood out from the night (although there were many) however, it was the enthralling music score. A fascinating fusion of classical and modern music was employed throughout the night, and it allowed the dancers to embody the remarkable stories of the Ganga and Murray rivers in captivating fashion. The composers Ms Mukherjee and Amit Diwadkar spent countless hours coming up with compositions that lent the hall an excellent ambiance. Especially memorable was the fusion between Indigenous Australian and traditional Indian dance to a modern beat – the costuming and lighting making this harmony all the more appealing.

17 year-old dancer Riana Das commented on the night, saying “Ha’Murray Ganga was different to other dances I have done. It was more than just looking pretty and getting the moves right, it was to convey the importance of water as our most vital resource”.

And of course, although the show was such a glamorous exhibition of talent, innovation and culture, the underlying message behind the night was made clear to the audience throughout. Kakoli Mukherjee said, “The performances were beautiful; it was a grand show, and people got the message. The impact will be there. People will start thinking about rivers and water. We want to keep freshwater rivers safe and secure for the next generation and let them flow forever.”

The protection of these amazing resources for our future was an idea conveyed not only by the current generation –the stage was lit up by the younger generation, including instrumental group “Sur and Beat” who performed the Australian and Indian anthems with great enthusiasm, as well as a great rendition of A.R. Rahman’s Maa Tujhe Salaam. Many of the dancers were not yet in high school, and it was refreshing to see the passion which they took to the stage.

The inspiration for the show came from Kakoli Mukherjee’s own experiences. Having lived her life by the side of the Ganga, she has been to the Himalayas and seen the beauty of the Ganga, but has also seen the deterioration.

“With all the environmental issues coming up now, this is one thing we need to do – protect the rivers, the water. I’ve met many Australians who feel for the river Ganga; they go to Benares, to the Himalayas and speak about the beauty of the river. Even they are doing their bit to save it.”

As a result of the fertile soil of the Ganga Basin, the river essentially lends 400 million Indians with a livelihood through crops cultivated in the area such as rice, sugarcane, lentils, oil seeds, potatoes and wheat. The presence of swamps and lakes along the banks of the river also provides a rich growing area for crops such as legumes, mustard, sesame and chillies. However, the extent of the pollution to the Ganga River is almost unbelievable.

Kanpur. These use large amounts of chromium and other chemicals, and many of these pollutants find their way into the river. Add to this the problem of corpses, the immersion of ashes, the floating of religious idols, and the (ironically) pure disregard shown towards the river, and it is clear that 1 billion litres of mostly untreated raw sewage is but a part of the problem.

The Murray River suffered from the lowest rainfall on record in 80 years in 2007, and a dramatic increase in the salt content sees it take but a meagre form of its past. However, it continues to supply 40% of Adelaide’s domestic water, and although efforts to alleviate the problems occasionally proceed, disagreement between the concerned parties stalls this progress. The Murray River stands, like the Ganga, on the brink of destruction.

But, while the problems continue to unfurl, and the waste keeps piling up, we must remember the hope the Ganga and Murray Rivers bring with them. The Ganga gives millions the courage, and the optimism to face each day, in the hope of a new tomorrow. The Murray’s significance to the Indigenous people of Australia is enormous, and both of them have lasted this far. As Ha’Murray Ganga highlighted: it is now up to us to ensure their eternity.