28 minute read

The Company you keep

from 2019-12 Melbourne

by Indian Link

PAWAN LUTHRA in conversation with author and historian WILLIAM DALRYMPLE

Pawan Luthra (PL): William Dalrymple, you have a very special ability to take us back into the India of the 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. You transport us to the darbars of the great Mughal kings, and one can almost smell the horses of the British garrisons. Your latest book, The Anarchy has just hit the stores and is on the best sellers list everywhere. It sits at the middle of the end of the great period of the Mughal Empire and the start of the Raj. What compelled you to write about this period?

William Dalrymple (WD): Everyone in India knows about the great Mughals, about Shah Jahan and the Taj Mahal. Everyone knows about Lord Curzon and the Raj and Queen Victoria and all that stuff. But in between those periods, you have this extraordinary world which breaks all our expectations. It's a world where it isn't the British Empire which is running India, but one multinational corporation, the first multinational corporation, the East India Company. It was not initially in any way involved with the government for the first 170 years, from about sixteen hundred through to 1770. It was, you know, a completely libertarian, ruthless capitalist organisation which performed the hugely improbable feat of taking over the richest empire in the world. And when it started, in the year 1599, just to give you the context of this, Britain was producing about 3 percent of world GDP. And at that period, the Mughal Empire was producing about 37.6% of world GDP. In other words, well over a third of world GDP. And for the first time in history, India, by which I mean most of modern India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and most of Afghanistan, which was what made up the Mughal Empire, had overtaken China as the world's leading industrial producer. I think today in India, there's a tendency to see the Mughals as these effete kings building ridiculously expensive tombs and prancing around in Bollywood outfits. In actual fact, from the point of view of economic history, they were the most successful Indian dynasty of all. And in the early 18th century, just when politically the Mughal Empire was in a sense beginning to fracture, their economic power was at its peak, largely due to the textile industry in Bengal. By Bengal I mean Greater Bengal, which embraces modern Bangladesh, Orissa and Bihar. That area was the world's manufacturing hub of textiles in the 18th century, the same way that Manchester became a century later. A million weavers at work, producing not just incredibly high quality and cheap and competitive cotton, but chintzes, kalamkaris, fine silks with weave so fine they were called bafthawa - woven air. This incredibly competitive and remarkable industrial produce conquered not just Europe - every Frenchman, every Dutchman wanted a kalamkari hanging around his bed - but also as further afield as Mexico. The East India Company initially rises up as basically the shippers of this material around the world. And they are parasitic or symbiotic with the rise of Mughal industrial power. So this was a period when India was unbelievably wealthy. Millions of pounds in weight of British and European gold and silver is pouring in not just from Britain, but from Portugal, Holland and Denmark. It seems right up until the middle 18th century that this is a loss of gold bullion to Europe and a gain to India that is irreversible.

This has been something which has been the case in Indian history since the time of Pliny in the first century, very austere Roman writer, contemporary with Jesus and Augustus, who complains that such is the decadence of Roman womanhood, that all they want to do is wrap themselves in gorgeous silks, rub their bodies with sandalwood paste from India and to hang from their ears Indian diamonds.

The idea that we are now seeing ahead of us of India as this big industrial growing power with an incredible future, is not something new and odd and surprising; it’s just a reversal to what has always been the case and only stopped being the case due to European firepower. And this very brief period between Vasco de Gama in the 1490s and 1947 - 500 years - is breaking what has otherwise been 3,000 years of economic dominance by China and India.

PL: William, tell us more about the East India Company in 1599. Paint us a picture about how it came into being, and how over a period of time the aims of this private company changed.

WD: In 1599, Shakespeare's writing Hamlet somewhere just downriver from the Globe Theatre. At the same time, we had a classic Tudor entrepreneur called Customer Smythe. Customer, because he'd been for the last ten years in charge of the London Customs and made a fortune out of that. He then made another fortune by founding something called the Levant Company, a group of 30 very rich merchants and ship-owners who pooled their capital and started buying spices from Aleppo, Cairo and Venice. And they did very well for about 10 - 15 years. And then in 1595-96, their whole business model was put to nothing by the fact that the Dutch realised that you can just sail round the cape and go to what we would now call Indonesia, particularly the Island of Run, and buy all the stuff at a fraction of the price, cutting out the Arab middlemen. And so Smythe appeals to the patriotic spirit of the businessmen of Elizabethan London, and calls upon them to try out a new business model that had only been tried out three times before. It’s something that's very obvious to us today and probably affects almost everyone in this room in one way or another, but which was a new invention at the time. This is the joint stock company, the corporation. The difference between the joint stock corporation and the guild system by which he had run the Levant Company, was that rather than a closed board of 35 investors, all of whom were involved in the running of the company, in a joint stock company, you have a small board, you keep the investment completely separate and anyone can invest. So as well as the big ship owners putting in a thousand pounds, five hundred pounds and so on, you have small London businessmen who contributed five pounds, 10 pounds, 15 pounds. And they didn't expect to be consulted about whether a voyage will take place or not. They just knew that they will get a share of the profits if it's successful. And this is a new invention. Today we take a corporation, the joint stock model, for granted, but this was a new invention of this period. They set sail to Indonesia. It doesn't initially look like it is going to be a great success because they've just got as far as Dover when the wind dies down and there's this strange summer calm and the expedition just sits bobbing off the White Cliffs for a month and everyone comes and laughs at them. They eventualy make it to the Island of Run, and there they see a Portuguese ship coming in the opposite direction. As they're all ex pirates, they just board the Portuguese ship, transfer the contents into their hold, and sail back to London, where they sell the contents for one million pounds. And that's enough to make all their fortunes. It does literally begin as an entirely piratical exercise, they make no bones about this. A lot of the seamen who had invested and who actually staffed these ships had been with Drake and Raleigh, Pirates of the Caribbean, think Jack Sparrow, it's this sort of world. Initially, they are always one step behind the Dutch. The Dutch have already been there. They've got better financial instruments. They can raise more money, they've got bigger ships. And in 1630, they actually beat the English out of the East Indies, which means Java, Indonesia. There's this famous face-saving treaty whereby the English handover to the Dutch, the Island of Run, which is then considered to be the most valuable property in the world, where all the nutmeg comes from. And as a face-saving device, the British get given a muddy island in the Hudson River called Manhattan, which, of course, isn't a bad investment in the long run. But at the time, it's considered rather a humiliation and by default, the English fallback on the textile trade, the second best option.

And that turns out to be their lucky break, because this is just the moment when the Mughals are rising up, with the same eye for aesthetic beauty which informs the Taj Mahal and those incredible textiles that we see in the miniatures. Their work genuinely changes the nature of textile design, and makes these textiles incredibly beautiful objects that everyone in any culture, whether Mexican, Frenchman, Dutchman, Chinaman or in the East Indies, wants to buy. And the East India Company rises up, on the back of the Mughal Empire. It's only in the 1750s that the whole thing changes gear and turns from an empire of business, into the business of empire.

PL: What did they do?

WD: The Company for its first 150 years is just a trading company. Because the Mughals are not particularly interested for some reason in exporting their goods, the Company steps in and acts as the shipping agent. It does very well. It beats local competition because it has better ships and it sells this stuff around the world. Then in the 1750s two things happen that change the nature of everything. The first is that the Mughal Empire has disintegrated. It reaches its peak under Aurangzeb, who dies in 1787. Shortly after that, the Persian emperor Nadir Shah, comes down from Persia. He defeats the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal, captures their Emperor Mohammed Shah Rangeela, marches him into Delhi, and six weeks later, leaves with 8,000 wagons filled with jewels, gold and silver, everything, in a single looting expedition back to modern Afghanistan. He takes the Peacock Throne in which is embedded the Koh-i-noor. He takes the Daria-i-noor, the other great Mughal diamond, which is now in the Kremlin in the sceptre of Catherine the Great. All this stuff just debauches off to the Hindu Kush. It's as if you just poured a fire extinguisher into the local boiler. For an art historian, this is one of the most wonderful periods of Indian culture. For literature, for painting, for music, for Indian dance, this is one of the most dramatically prolific and culturally fascinating periods of Indian history. But politically, it means that the Mughal Empire, which was this unstoppable force of four million men under arms, has now fragmented into lots of little kingdoms. And not just the British or the English East India Company, but the French companies, between the two of them, begin hoovering up these little tiny states, which are culturally and economically very rich, but which are militarily and politically vulnerable. The French show the way in 1740: they are the first to train up seepoys, local Indian soldiers, in the latest military technology from Europe.

Europe has just fought two big wars - the war of the Austrian Succession and the war of the Spanish Succession - and Frederick the Great of Prussia who's a military genius, has transformed warfare with simple little changes to the nature of the cannon. He puts an elevating screw on the back of a cannon. He makes them portable so horses can move them around battlefields. He invents a form of musket that has a bayonet and which can be rapidly loaded and fired in file firing - one line kneel down and fire as the next lot load, than that lot fire, so that you get continual firing by infantry.

These techniques, none of which are rocket science, are quite easily copied, and are brought to India by the French and they train up local guys to do it. And it's incredibly effective. The first time it's tried out is in 1740, at the Battle of Adyar, which is now southern Chennai. 70 French company seepoys see off 3,000 Carnatic cavalry. From that point, for about 30 years, the English and the French realise they can more or less see off any army with this new military technology. The English company then tries this out in Bengal with Siraj-Ud-Daula at the Battle of Plassey, then again at the Battle of Buxar in 1764.

To everyone's amazement, most of all to the Company's amazement, they haven't planned this particularly. They found that using this new military technology, they are in a position to just take over north India. This incredibly rich, incredibly civilized, but now vulnerable, fractured and disunited kingdom is simply conquered in as little as 50 years. And how they do it is astonishingly audacious. They train up local Indian warriors to use this new technology. The Company seepoys grow from 20,000 at the time of Clive to 50,000 by the time of the Battle of Buxar, and only forty years later in 1799, to 200,000 seepoys. Which is literally double the size of the British Army. The British Army, which is barely involved in India at this point, is only 100,000 men and is now engaged in the struggle with Napoleon. But the Company which only has thirty five people in its head office, and in Bengal never has, even as its peak, more than 2000 white guys sitting in Bengal, train up 200,000 Indians to fight other Indians.

To do this, they borrow money from Marwari and Hindu bankers.

If you wrote this as a novel or a film script, you'd be laughed off because it's the most improbable story.

Why would anyone fight their own brothers and sisters? Why would anyone lend money to a voracious corporation that was involved in something so violent? Well, the answer is, the soldiers got paid twice the salary of any other military unit in the country.

And why would the Marwari traders and the Hindu bankers of Benares, Allahabad and Patna lend money to the Company? The answer is in that case, that it may have been foreign as in it was Christian, meat eating, white skinned, from Europe, but as far as the Marwari money lenders were concerned, they were both financiers, they spoke the same financial language, they understood about repaying loans on time with interest, they had civil courts where business contracts could be defended and upheld.

Calcutta initially was like Dubai or Singapore today. It was a tax haven where you could escape tax you had to pay elsewhere. You could grow and cultivate fortunes, which is what the Marwaris were doing. The Marwaris, originally from Marwar in Jodhpur, went to Calcutta for the same reasons people go to Dubai and Singapore today. They didn't have to pay tax. Simple as that.

The Company is quite ingenious in realising that and playing on that. So the next thing it does in the 1790s, is it begins to break up the old Mughal estates, huge areas of land, and puts them up for auction. Who buys this stuff? The new rising Hindu middle class families like the Tagores, the Debs, the Mullicks. And by buying into this world, they become part of it. They get subsumed into this Company world and they make the decision, rightly or wrongly, that the Company which may loot assets, strip, plunder and be incredibly violent to its enemies, is for them the least worst option financially, that their capital is safe with it, and that they prefer it to the Mughals or to the Marathas. The Marathas raided Bengal in the 1740, looted, raped and pillaged. So they're not going to go with those guys. So they make this decision. And Bengal, as this industrial hub, has the resources: it paid for the Mughal Empire first and then it paid for the Company. It generates enough revenue that when Indian armies catch up militarily with the Company by the 1780s, Tipu Sultan, Haidar Ali and the Marathas have all trained up armies in the same techniques and can beat the Company on the battlefield. But it still prevails because it has more resources. It's a horrifying story from a variety of fronts. Think Avatar - the movie where, you know, the mining company goes and takes over another planet. It's the same sort of story. It's a very canny, ruthless corporation that manages by military force and by financial inducement.

PL: How did it exploit Bengal in the famine of 1770?

WD: So the company screws up, as corporations often do, through greed. We've seen in our old days many examples of corporations which seem impregnably strong, impregnably dominant economically and whose share price seems immovable, suddenly collapse when circumstances change. And this happens to the company in 1770. 1764, it's finally conquered all of North

India with the Battle of Buxar: it takes them only six years to asset strip, loot and plunder Bengal so thoroughly that when the famine of 1770 comes, there are no surpluses. There are no granaries stocked with grain. The Company is not in the business of setting up soup kitchens; as a company it’s there unequivocally to make a profit in the same way that Goldman Sachs is there to make a profit today. So when the famine comes, the Nawab of Awadh at the same time builds imambaras and employs 100,000 people. And they live. In Bengal instead, one million Bengalis die, a fifth of the population of Bengal. The Company - by sending seepoys out into the villages and gathering tax revenue by force, and hanging anybody who doesn't pay - manages to maintain revenues at pre-famine levels. The shareholders in London vote themselves an increased dividend from 10 percent to 12.5 percent. This happens for two years. Then finally, in the third year, there's nothing left. As one Scots writer and whistleblower writes, ‘They have picked the Bengal bones to the marrow and it lies bleaching in the wind.’ The share price sinks, 30 banks collapse across Europe. It's like the subprime, but only worse. And this is the moment that for the first time in its history, the government begins to take an interest in the East India Company. Up to now, they've been a valuable source of customs revenue, and no one has asked too many questions about where this money is coming from. It provides a third of British customs and it pays its taxes and the government's fine with it. Suddenly, whistleblowers are writing reports of a million bodies in the streets of Calcutta, the Ganges clogged with corpses, vultures and dogs barking at human remains, clouds of flies and vultures like some biblical plague. And suddenly everyone in Britain wakes up to the fact that all this stuff is going on and there is outrage. There are angry editorials in the newspapers. Parliament has to bail out the Company because it is literally too big to fail.

So the Company in 1774, through its own greed, puts itself in a position where it isbailed out by the government. So the government now has a regulating role over it. And from that point onwards, it changes from this buccaneer libertarian organisation, unregulated, unwatched over, just a source of money, towhat would today be called a public-private partnership. Eventually in 1857, it screws up a second time during the Great Indian Uprising, and three hundred thousand are killed in the reprisals. And as India is nearly lost to Great Britain, the government rolls up the Company completely and in our terms, is nationalised.

PL: Why did the British government support the East India Company?

WD: Up to 1774, Parliament has been very thrilled with the company because it's a very safe investment. A quarter of Parliamentarians have shares in the East India Company growing to, I think, 40 percent by 1770. The only resentment felt against the Company is not about the plunder and immorality of its actions in India, it's more to do with the fact that people are jealous of these Nabobs coming back. These men are coming back aged 35, buying up parliamentary seats, buying up big country houses around Britain. There is social resentment against these young men, swaggering, throwing money around, breaking social convention. They are often from fairly humble backgrounds, but now they're the new rich. So the initial opposition to the Company is more social and snobbery than outrage about human rights or anything else. By 1770, there is genuine outrage at everything. The Company is bankrupt and yet at the same time, the dividends have never been higher in terms of the amount of money being remitted from India to Britain. I think the same year that a million Bengalis die, 1772, 15 million pounds is remitted back, in that day's currency. So what had been seen to be a very good thing for Britain, had been the country's leading employer, had been the largest payer of tax and customs revenue, suddenly came to be seen as this monstrous, violent force that was somehow involving the country in war crimes and murdering. Horace Walpole (writer, historian and politician) writes in his diary, “This time, we have outdone the Spanish and the Portuguese in Mexico. They at least had the excuse of faith. We have done this for profit.” So suddenly the country wakes up to what's going on. And by 1857, the whole thing is nationalised and becomes the Raj.

There's two very different periods of history when you're dealing with the British in India. One, that has remained in the public eye: it is Kipling, Queen Victoria, Merchant Ivory films, smiling Maharajas, all that stuff. But that period is only 1858 to 1947, only 90 years.

A bit below the waterline, which we rarely see if ever in movies, is the Company period. In Indian popular culture, there's Satyajit Ray, The Chess Players (Shatranj Ke Khilari) and Junoon about this period.

There are different pros and cons. The Company period is more exploitative, asset stripping, more plunder, more loot, and yet at the same time it's more collaborative. The Company intermarries - a third of British men in India marry Indian women. Most Indian most company businessmen will have Indian partners, whether it's in the indigo trade or the opium trade. (A lot of the opium trade is in the hands of Parsis out of Bombay, for example. I was actually in the headquarters of Jardine Matheson in Hong Kong giving this talk two nights ago, Jardine Matheson being the private company which in a sense replaced the Company in the eighteen sixties as the centre of the opium trade. At the top of the stairs in the penthouse where I was giving this talk, is this huge, massive portrait of Jamshedji Jeejibhoy, who is the JJ of the JJ School of Art and the JJ Hospitals, and this whole variety of philanthropic organisations. That money came from the opium trade.)

The Raj, which follows it, post 1857, is slightly different in that it has all this rhetoric about bringing Western civilisation to Asia, rescuing the poor benighted natives from Hinduism and all the things that Victorians disapprove of. And they are very racist. They have the all-White clubs, ‘No dogs and Indians allowed’ etc. That's the way of the Raj. And yet in order to back up their rhetoric of civilisational mission, they build hospitals, universities, communications. So in 1947, when Britain leaves India with only 7 percent of world GDP rather than 43 percent or whatever it was at the peak, it nonetheless leaves India with the best communications in Asia. The best education system in Asia. And the best health system in Asia. And for the first 20 years of Indian independence, if you're in Singapore, Malaysia, you will send your kids to Delhi to be educated. It's only with the rise of South-East Asia in the ‘60s and ‘70s that that ceases.

You know, I don't know which is worse or better. You don’t particularly want to be an Indian under either, but they are different in their iniquities. The collaborative plunder of the Company or the racist civilisation mission of the Raj. But what is certainly the case is that we remember the Raj. We've forgotten this period when India most improbably was conquered by a single London business.

PL: You mention the Marwaris - or the JagatSeths as the Mughals called them, the Rothschilds of India as you call them. You claim that they lent the Company money to take over India and exploit the Indians themselves. How has contemporary India reacted to this statement of yours?

WD: Well, I don't think the Marwaris would have seen it like that. They would not have seen themselves as funding the expansion. The first thing the Jagat Seths do is actually pay Clive to topple Siraj-Ud-Daula. It's a palace coup that they're paying them for and they don't calculate on the Company then being the puppet masters. But the Hindu bankers continue to fund the Company because they see it as the safest place for their capital. It's that simple. They're businessmen. They have to make a judgment on which is the most profitable. Who is going to repay their loans? The answer is the Company will appeal. Business is pure business. They see it as they do today. For the Company ultimately, its initial success is due to military superiority. Its final success is due to two things. One, it has Bengal with all its revenues, and two, the bankers back it rather than (other forces at the time). It's that simple.

PL: The book ends when the Company ends. Of course there was murmur in the British Parliament since the early 1800s about the dangers of allowing a trading company - one that the British government had so little control over - to rule over 100 million people. It caused rampant corruption, seeing a small group of men make an obscene amount of money. In 1833 the British Parliament passed a Bill removing the Company’s power, but it was so strong that it wasn’t until the 1870s that it finally died a quiet death, Queen Victoria taking over as ruler of India. Yet, your last sentence is quite chilling. You write, “Four hundred and twenty years after its founding, the story of the East India Company has never been more current.” What are the contemporary ramifications of the East India Company?

WD: There are really two stories in this book. One is about Company’s conquest of India, which is a historical story. The other story, sort of a meta story in itself that runs all the way through the book, is the story of the power of corporations versus the power of the state. And that, of course, is a story with an unfinished conclusion. It's a contemporary story. I've just come back from a book tour in the States. Elizabeth Warren is bringing up these issues about the power of big pharma, big data, big money. The story of the Company is the story of the institution which first invented so many of the things we associate with corporations today. Corporate lobbying is invented by the Company, which is also the first company to really be multinational and to straddle the globe. It's the first company which realises that a rich company can actually change foreign policy and that if you influence parliament, the interests of your shareholders consume and become the interests of the state. Every modern democratic nation of the world has some stories of this being the case in the 20th century. There were three famous moments when corporations brought down governments. 1953, Anglo Persian Oil Company gets rid of Prime Minister Mossadegh of Iran, the only freely, democratically elected Iranian premier. The first thing he wants to do when he comes to power is to nationalise the oil industry: the CIA and MI6 topple him and replace him with the Shah. 1955, Guatemala, the United Fruit Company owns 42 percent of the cultural land:asocialist government is elected which promises to redistribute land more evenly to the people of Guatemala. The government is toppled by the CIA, producing the phrase Banana Republic. 1973, Salvador Allende in Chile is brought down by the CIA. (Following this, we see) the most brutal human rights abuses in South American history. So you don't have to be a, you know, vegan, anti globalisation, bandana-wearing nutcase to recognise that corporations do do this sort of thing. It's part of history. Corporations can bring down governments. They can skew foreign policy. They can change the way governments operate. And the Company not only is the first to invent corporate lobbying butto realise that the 40 percent of employees in parliament who own shares can be used to influence foreign policy in its favour. They also realise that you can bribe parliamentarians. So in 1697, for the first time in world history, the East India Company is caught bribing members of Parliament with share options if they vote to extend its monopoly. Now this obviously is something which continues in the shadows in every democracy in the world. Corporate donations in any country outbid private donations, and they come with some sort of quid pro quo which is never made public, whether it's Adani or Advani or Ambani. The most obvious question in modern history was, given the closeness of Dick Cheney to Exxon, was it an accident that it was Iraq that was invaded after 9/11, when Iraq clearly had nothing to do with 9/11? So the way that foreign policy can be changed by a big corporation has its roots in the history of this company. We're not just talking a story, a specific historical story of the conquest of India. This book is about the origins of corporate lobbying, corporate influence and the ongoing and unfinished story of how far corporations can change the world.

Darshak Mehta (questioner from the audience): What do you think the Indians should have done to resist, with the benefit of your hindsight? Were they too acquiescent? Were they too gentle? Were they too stupid? Were they too greedy to make money? What should they have done differently?

WD: Indians have never been stupid and they've never been gentle. The story of this period is full of incredibly violent, clever, ruthless people. The Company doesn't even begin to make a toehold in India until the Mughal Empire breaks up. So the answer to that question is disunity. The great problem with India at this period, several Indians realise this, is the disunity. I mean, there are brilliant Indians in the story. There are Indian military geniuses, financial geniuses, but they don't get their act together in a united front. And to say one last thing, which I haven't said, if you were to look for one positive thing from the Company, what it does do and what in a sense is its greatest legacy, ironically, is it unites India, and it creates a united Indian army. While India has been a geographical, cultural, spiritual space for millennia, it is never until this period a united political space. Not with Ashoka, not with the Guptas, not with the Delhi Sultans, not with the Cholas, not with the Mughals. It's the Company that first unites this area. And the army it founds is still the basis of the modern Indian army. Regiments like Skinners Horse and Gardeners Horse still exist to this day; the officer's mess is filled with cups and trophies and pictures of this period. And so if you were to look for one bright outcome from this, far from an elevating story of loot and plunder, it is that, ironically, India becomes united politically for the first time through this horrible process.

Teddy Mehta (questioner from the audience): William, I'll drag you into the current age. You wrote once about the shrinking of the British Empire. Is Brexit the last chapter of the shrinkage? Do you think Empire is finished?

WD: Long finished, obviously. I mean, what's finished probably in the last three years, is the United Kingdom. I'm Scottish. I voted for the union when we had the last Scottish referendum.

If we have a Brexit England, which is antiEurope, insular, belligerent and ignorant, it's not just the Scots who are going to vote themselves out. It's the Irish and the Welsh, too. And people forget the Britain is very recent concept, 1707. I would imagine at the moment that we'll see the break-up of the United Kingdom within the next decade and that Scotland will probably remain in Europe. I certainly hope to have a European passport again before too long.

Rosemary Mula (questioner from the audience): William, you've obviously done a lot of research going back so far. Did you find a consistent record of what happened then? How did you sift through it to come to the conclusions that you have?

WD: There are two very different problems here. You have the Company which keeps every single chit for 300 years – it’s said there are 35 miles of Company records just in the British Library alone and an equivalent amount in Delhi in the National

Archives. And then, you know, to get the other side of the story, you need to get the Mughal records. These are far more complex and difficult to access because they’re in Persian, only very latterly in Urdu. And they are split up, some in the National Archives, some in British Library, but quite often in small provincial archives in places like Patna, Tonk in Rajasthan, Rumpur in Utter Pradesh. Getting hold of that stuff is the main challenge. That's where I devoted my primary research, to fill out that picture.

PL: What took you to India in the first place?

WD: Total accident. Actually, I wanted to be an archeologist in Iraq. I had a place in the British School of Archaeology in Baghdad, and it got closed down by Saddam Hussein, who claimed it was a nest of British spies, which it probably was for all I know, I never got there. So I ended up going with a friend to India in 1984. I'm still there.

PL: What fascinates you about India?

WD: You could have asked me that question at any point in my life. And I’d probably give completely different answers. It's allowed me to do a whole variety of different careers. I've been at different times a foreign correspondent, a historian, a travel writer, festival organiser, a photographer. It’s like I'm like a child in a sweet shop there. And it's such a rich place to write about, to photograph, to think about, to know about.

PL: What frustrates you about India?

WD: Oh, so much. Whatever love I have for the country is equally matched by the daily frustrations, like when the bijli goes or the Internet disappears for five days in a row, or you're stuck in a traffic jam for seven hours… The frustrations drive me up the wall, but I’m enjoying everything else enough to put up with the frustrations

PL: With all your research from the 15th to the 19th centuries and beyond, which character, living or dead, do you identify with the most?

WD: I think I would very much enjoy being one of those White Mughals…Sir David Ochterlony with 25 wives would be quite a good start (laughs). Each of his wives had an elephant and they would do this wonderful march around the Red Fort every evening. Then they’d return to his library, with Ochterlony in his Fab India sort of kurta pyjama, turban on his head, dancing girls in front and a eunuch behind. And best of all, the outraged Scottish ancestors staring down from the picture rail above, wondering what's happened to Davy after a few years in the Indian salon… And well they might ask!

PL: There are deep links between your family - and that of your wife Olivia Fraser - and India.

WD: Both of us are from the same sort of class of Scotsmen who always had social aspirations greater than our wallets, shall we say. And so both families intertwined with India. Throughout this period, there are three Dalrymples in The Anarchy, one of whom is linked to this continent very closely.

Alexander Dalrymple was an East India cartographer, who mapped the whole west coast of India and then planned a settlement which ultimately became Singapore and then wrote a book called The Great Southern Continent. He became convinced that what Tasman had seen on one side and various other French sailors and Spanish sailors, must be a continent in the southern ocean –Australis as they called it. He came back from the East India Company in 1767, went to the Royal Society, and managed to get money to go and find this continent that he was sure existed in the South Seas. But he was East India Company, not Royal Navy. At the very last minute he discovered that he wasn't going to have complete command of this expedition because it was a Navy ship. So he resigned, and some character called James Cook went and led the charge, for which you would all be learning to spell Dalrymple!

PL: Last question: do you have a comment to make on contemporary India?

WD: I'm a great optimist in terms of economics. It seems to me that everything has to go wrong in order to stop India becoming the next great economy. Wherever they go in the world, Indians succeed there. As soon as they’re let out of India, they will rise to the top. We now currently have Sajjid Javid and

Preeti Patel as our home minister and foreign minister in Britain. And this has happened in a generation. In Canada a Sikh is now the deputy prime minister under Trudeau. The people of India are hardworking. They have incredible resources. And India will be the second economic power in the world, I'm quite sure, by the time I die.

I'm not a fan of this government, though. What's happening in Kashmir will undermine India, is my personal view. I think there are some very dangerous things going on with the Indian press and the silencing of the opposition and the absence, frankly, of an opposition. That's not Modi's fault, the fact that the Congress Party has disintegrated. Currently, I think it's very worrying. I hope that out of this, a new opposition will emerge, giving India the two-party system it needs. But despite all that, I cannot see a future where India cannot succeed. I think its success is assured unless something terrible happens. My big fear is that by focussing so much belligerence on Pakistan, by all this action in Assam, disenfranchising a million Assamese Muslims, the whole action in Kashmir and so on, India will forget the far greater threat that China poses. China at the moment is much richer, much more economically and militarily advanced than India. My fear is that we'll see another 1962 and that Modi could suffer, ironically, the fate of his least favourite politician Nehru. Yet India remains amazingly blind to the threat that China poses to it, by focussing all its anger on Pakistan, which is a very minor player in the world stage. There were points in the first decade of the century when the Indian economy was growing every year by the size of the Pakistani economy. It's that level of disproportion. I think India needs to refocus its anxieties much more on China and the String of Pearls, the deep water ports and Trincomalee and Gwadar and elsewhere, because I think China is the force that India will ultimately have to reckon with in the next 20 or 30 years. It's the relationship of these two powers that will determine the future of this planet.

PL: And that's a historian speaking, who can draw on his research and experience. Thank you for your time with us, William.

BY PREETI JABBAL

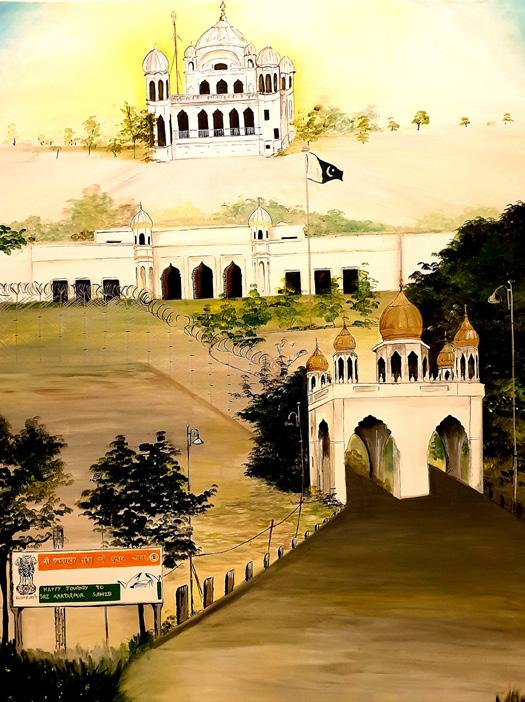

It took Pakistani workers only a few months to build the Kartarpur Corridor, creating a pivotal moment in the history of India-Pakistan relations. On the other side of the world, a Melbourne artist painted a likeness of it, within 48 hours, to be presented to the Chief Minister of Punjab during his visit to Birmingham UK. Both were managed in record time.

Haneet Grover Ahuja (Nitu) of Melbourne Art Academy was commissioned by Indian Government officials in UK to create a special piece of art to be gifted as a token of appreciation to Captain Amarinder Singh. The 3ft x 4ft acrylic on canvas now adorns