3 minute read

NO HIDING THE BLATANT CHAUVINISM

from 2019-02 Melbourne

by Indian Link

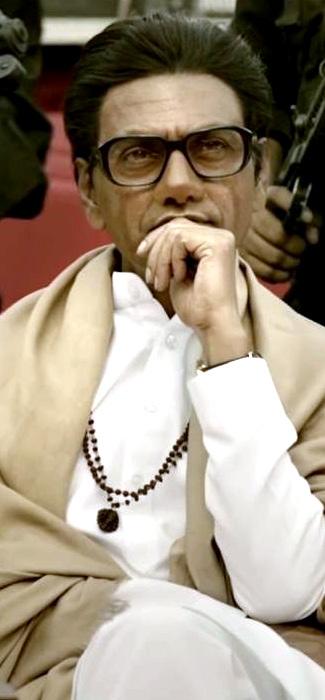

Thackeray

STARRING: Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Amrita Rao

DIRECTOR: Abhijeet Panse HH

Bal Thackeray - sorry Balasaheb Thackeray (an unsuspecting character in the film gets slapped by a Shiv Sena cadre for uttering the Demi God's name without the reverential suffix) - played the chauvinistic card with a masterminded focus. He knew how to tap the Marathi manoos' latent pride and also how to harness it into a violent outpouring.

Many of his opponents, including the unfortunate Morarji Desai (unfortunate, as he is played by Rajesh Khera) thought of his campaign to cleanse Maharashtra to be almost a ratification of Hitler's Nazism.

The film certainly does not squander the opportunity to portray the man as infinitely intolerant of migrants. That he was, was a well-known fact. But did anyone ever think that his blatant chauvinism and his politics of ethnic cleansing would one day be so unabashedly celebrated on celluloid?

Writer-director Abhijeet Panse celebrates Balasaheb's spirit of separateness with a straight forwardness that we immediately recognise as a sign of traditional entitlement which sanctions certain behaviour among males as "normal".

For outsiders - and who is not an outsider these days - the normalising of cultural marginalisation may seem like a celebration of a culture of anarchy and despotism.

Sanctioning bloodbaths is not something we associate with charismatic national leaders.

Siddiqui plays Balasaheb as an impatient, intolerant man of many words and even more action. At the start we see him quit his job as a cartoonist to start his own Marathi paper. In Panse's Maharashtra in the 1950s there are migrants everywhere - jostling, pushing and bullying Marathis on the streets and out of their jobs. Something has to be done, and who better equipped to tap into Marathi pride with a hammer? supporting cast is largely wasted, barring Jishu Sen gupta as the Rani's husband, somewhat delicate.

Apparently the inflammatory speeches are all used in the film just as the Great Man made them. Balasaheb had a hypnotic hold over the audience. Nawaz seems to think he has a similar sway. In his last film he recited Saddat Haasan Manto's revolutionary thoughts with a fervent lucidity that gave the actor a sense of ownership over the words. Here the Balasaheb speeches sound deeply ironic, coming from an actor has been marginalised on many levels in different stages of his life.

Nawaz and the film's director choose to overlook the irony of an ethnic leader saying the nation always comes first to him.

"I always say Jai Hind first, and then Jai Maharashtra," Nawazuddin's Balasaheb proudly tells Avantika Akerkar's Indira Gandhi.

Mrs G's arched eyebrow at that declaration is truly a chart-topping moment in a film that legitimises hooliganism and elevates extra-constitutional muscle power to the summits of validation. There are some interesting unknown actors playing Balasaheb's devotees - I loved the veteran who plays his father and mocks the ‘Saheb' in his son's name in a way no one else would dare.

Nawazuddin plays Thackeray with the crafty casualness of an over-confident actor who is rightly arrogant about his skills. The other actors walk by in the gallery of bhakt sanointing and celebrating the cult of Thackerayism with a religious fervour, the violence and bloodshed notwithstanding.

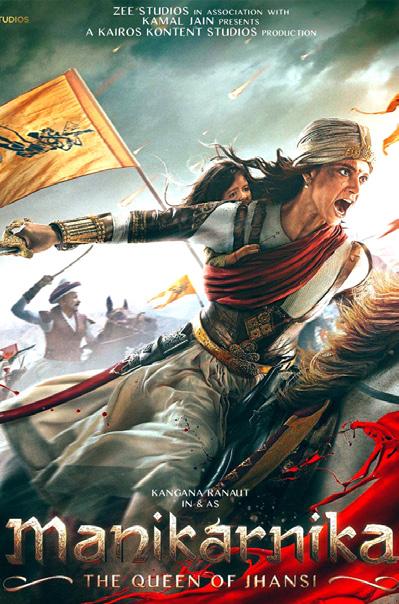

More than the politics of invasion and acquisition I like the petticoat politics of the film, the friendship between Rani Laxmibai and the uncommonly valorous commoner Jhalkaribai (played with spirited affection by Ankita Lokhande).

In fact, the way all the women of Jhansi come out of their kitchens to battle it out on the preying field, is one of the great charms of this flawed but fabulous fable, as are Prasoon Joshi's dialogues which suggest a kind of deep-rooted empathy between history and girl power.

The British, as per the demands of all colonial dramas in Indian cinema, are portrayed as sadistic buffoons. One particularly distasteful sequence has a nasty British General hanging a young girl by a tree after he gets to know she is named after his pet peeve Laxmi.

Manikarnika could have easily avoided these violent bouts, concentrated more on creating a drama of disambiguation that destroyed the Indian kingdoms during the British Raj. I am sure there was more to Rani Laxmibai than the expensive saree and jewellery, the mystery and the dancing eyes. But what we see is what get in this film. And that is quite a lot.

All said and done, Manikarnika moves us, though not in ways it should have. There is too much going on at any given time to focus on the heart and thoughts of a woman who defeated the British with a child in her lap. Did the child ever wet the Rani's costly silk sarees? We would never know. The characters of this film are not prone to human frailties. Subhash K. Jha

Subhash K. Jha

But hey, there is also redemption. After a brutal communal riot we see Balasheb bring a Muslim family to his home. He even allows the man to do his namaaz in his living room.