3 minute read

Not lost in translation

from 2018-05 Melbourne

by Indian Link

BY CHITRA

There is a vast ocean of literature in the vernacular languages of India, and each language has its own rich history and traditions. Alas, most of us have little or no idea of what they are. Unless these works are translated into another language or English, we don’t really get to enjoy or experience those fantastic literary works.

Often, when reading books by authors of Indian languages, I am struck by the sad fact that apart from their own language, they are likely to be more familiar with English language literature than towering writers in other Indian languages such as Valalthol in Malayalam, Kshetragya in Telugu and Bharati in Tamil, to name a few.

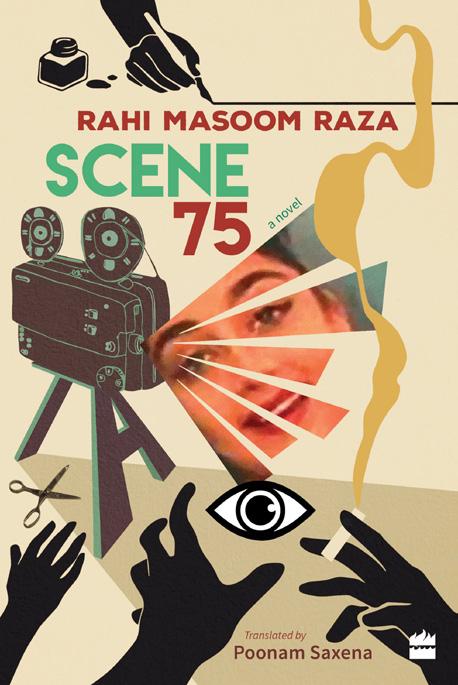

So we must thank Poonam Saxena for translating the late Rahi Masoom Raza’s searing Hindi-Urdu novella, Scene 75, written in 1977 (Harper Perennial, 2018) because for the first time, non-Hindi/ Urdu readers can finally get a taste of that author’s literary tour de force.

Raza skyrocketed to fame as the scriptwriter of B R Chopra’s TV serial Mahabharata in the 1980s, although he had worked on a range of ‘serious’ and ‘masala’ movies in Bollywood earlier. His considerable writing skills had been recognised when he was awarded ‘Best Screenplay’ twice.

Lurking underneath the Bollywood banter, though, was a more serious author and social critic who had already written acclaimed books such as Aadha Gaon and Topi Shukla that pilloried hypocrisy and greed in modern India. When Abdul Hamid, an Indian soldier from Ghazipur, who won the highest honour for bravery, the Param Vir Chakra, for single-handedly destroying seven enemy tanks in the 1965 war, the then Defence Minister YB Chavan called upon Raza to write his biography.

Here was an author capable of digging deep into society and laying it bare in incisive prose while simultaneously making his way in the world of commercial Hindi cinema.

Although he had written screenplay for some memorable Bollywood movies, he often found himself quite repulsed by Bombay movie industry of the 1970s in many ways. This conflict between the commercial writer and social critic is what dominates the hero of this 1977 novel, Ali Amjad.

Amjad comes to Bombay from Benaras to write for films, but is stymied by the industry’s rank hypocrisy. In his description of it, Raza brings to the novel insider’s an insider’s understanding of Bombay and the Bollywood movie industry: ‘fixed’ film awards, manipulative heroes, promiscuous heroines and social climbers and scores of hangers on, who wait desperately for that first break in the movie industry.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that Scene 75 is largely autobiographical. Raza was born in Ghazipur in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, and studied at Aligarh Muslim University, but developed a distaste for religion quite early on. His novella does not skirt the issue of ‘Muslim as the Other’ though. Indeed, this theme — the question of identity and Hindu-Muslim relationship — haunts most of Raza’s novels. He evokes the experience of being a Muslim in India better than most other writers.

Although written in the 1970s, Scene 75 retains its freshness and relevance, and does not feet one bit dated. The writer’s literary style is reminiscent of the famous Urdu writer, Saadat Hassan Manto in its candour and minimalism.

Saxena, who has earlier translated another Hindi classic, Gunahon ka Devta by Dharamvir Bharati, does a commendable job of retaining Raza’s voice, and avoids the temptation of superimposing hers on the original.

Classic Lives On

We now turn our attention to another recently translated work – this time considerably older than 1977! The famous play – Mricchakatikam: The Clay Toy-Cart, was written in Sanskrit 2500 years ago purportedly by Shudraka – and is of a slightly different genre than Kalidasa’s. Ever since it was rst translated into English in 1905 by Ryder, it has been adapted and performed on stage in the West many times.

The theme of the play has a certain universal appeal: the plot of two starcrossed lovers caught in a larger political intrigue that is being played out lends itself to adaptation into any culture or time. It has all the hallmarks of a thriller: Vasantasena, a nagarvadhu or rich courtesan, is pursued by a poor Brahman Charudatta, but their romance becomes intertwined with palace intrigues when the King’s brother-in-law covets Vasantasena as well.

That a play two and half millennia old can resonate among so may audiences worldwide is a testament to the genius of the author. The new translation is by Padmini Rajappa and although it is not quite as brilliant as Ryder’s, it is de nitely worth a read, especially if you have not read it at all in any of its translations.