4 minute read

Focusing on tiny tots Explaining health issues to children

from 2013-09 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

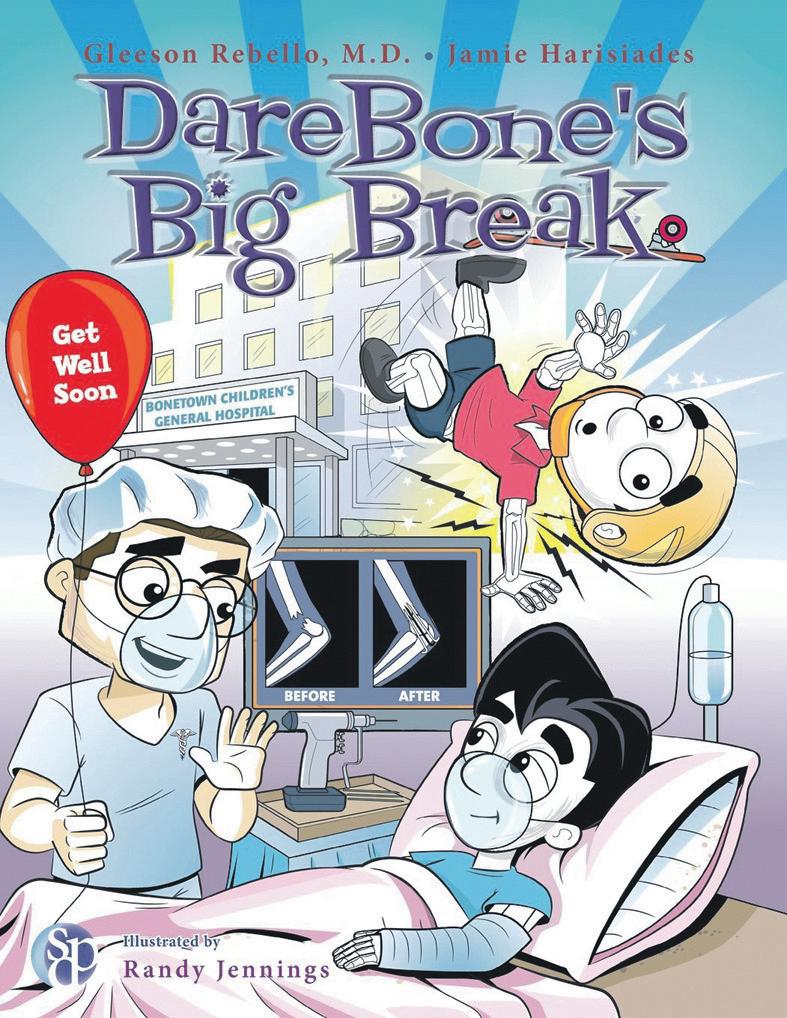

It’s large, it’s colourful and it’s attractive.

DareBone’s Big Break by Gleeson Rebello and Jamie Harisiades, is the kind of book that even draws adults to go through it and, before you realise it, you’ve picked up something new.

Its main author, Gleeson Rebello, is a pediatric orthopedic surgeon born and brought up in Goa. He is currently a consultant in the department of orthopedic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, and is on the faculty of the Harvard Medical School.

The book describes itself as “a tale of trauma, treatment, and recovery in rhyme”. It deals with a story from everyday life: a child gets injured on the playground, and ends up in the emergency room.

Rebello says his attempt is to “educate without intimidating” and “entertain without underestimating”. So this book packs in poetry, humour and, importantly, medical accuracy.

DareBone is the boy who suffers his first major injury - a broken elbow. We meet him together with his “wise-cracking sidekick,” the dog Wag-A-Bone.

Given the authors’ medical backgrounds, DareBone not surprisingly meets a number of “medical heroes,” including the orthopedic surgeon, as he journeys through surgery and recovery.

“The book was written with the aim of raising the bar in terms of explaining the nuts and bolts of everyday medical practice to a smarter generation of children, without underestimating their ability to pick up complex concepts. A secondary aim of the book is to make medicine and biology ‘cool,’” Rebello says of the book.

He sees the book as “very technical from an orthopedic standpoint, but at the same time funny and easy to comprehend”. It is aimed at children of 4-10 years, as well as their parents and healthcare professionals, or educationists who deal with children of that age.

“The response to the book has been very encouraging both from healthcare and non-healthcare-related professionals. It took two years to write it once I thought of the idea... (There also was) interacting with a lot of frightened children with broken bones in the emergency room and my clinic, who were mostly afraid because of lack of knowledge of what was to follow,” Rebello said.

This is planned to be the first of several books from Rebello, who partnered for this job with Jamie Harisiades. They will speak about common childhood conditions like allergy, autism, asthma, and obesity.

Rebello is also working on a similar book on childhood obesity and also create an app out of DareBones Big Break

Rebello trained at the Goa Medical College, Christian Medical College in Vellore and the Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, before he joined Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, as a research fellow and on a staff position in 2008. His father, Francis M. Rebello was closely associated with a local Konkani newspaper in Goa, founded through public donations in the 1970s.

Not surprisingly, Rebello says he caught the writing bug “right from my schooldays”.

“Every doctor has thousands of stories inside him. The story of his professional life is but a collection of stories of his patients’ lives”.

Frederick Noronha

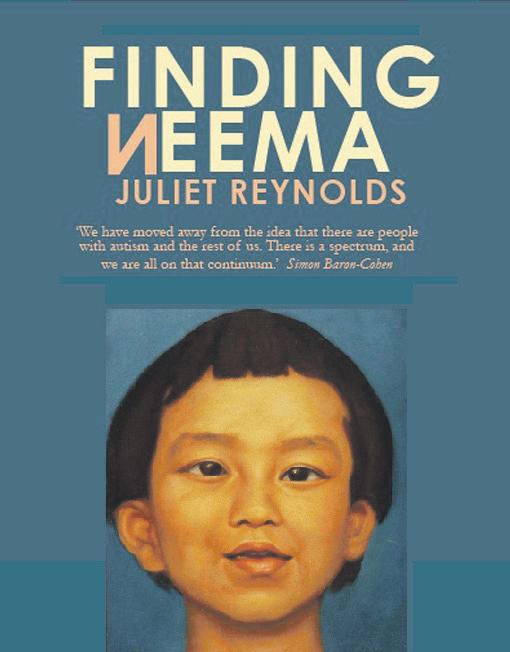

Neema: Muse and social glue

Reading Finding Neema is almost like living a life vicariously. Juliet Reynolds, the author of this memoir, has years still to go and a bit of writing still to do. Through the book, though, this filmmaker and art curator offers readers a candid and self-reflexive account of her marriage, her work and, most of all, her child. Yes, her child. She is legally only the guardian of Neema, the autistic child of a Nepali mother, but it is clear that she derives much of her own sense of self in relation to him. In finding Neema, thus, it is almost like Reynolds finds herself.

The memoir is a linear narrative, beginning with Reynolds’ acquaintance with the man who would be her husband, the one who would ultimately make her think of India as her own. Anil Karanjai is the not-so-widelyrenowned painter of what is known as the Hungryalist school that took roots in the early 1960s in West Bengal, to shake off, once and for all, the colonial yoke in poetry and art. Reynolds would showcase Karanjai’s works and find solace in his arms.

Karanjai appears, in this memoir, as a man only too willing to go with the flow, spontaneous in his expression and deeply perceptive, able to communicate with ease across cultures and continents. Not a man conventionally trained or educated and with little care for wealth. Precarious living seems to come naturally to him. And after his sudden death, Reynolds wonders if she knew all she should have about his visits to the doctor. Could he deliberately have left a condition untreated? Given the character portrayed in the narrative, that might well have been the case.

The couple remains financially insecure as Reynolds gives up a teaching position to explore other avenues and Karanjai’s paintings bring them only an unsteady income. The portraits he paints are sometimes commissioned, but the flow of money is not regular.

So where does Neema fit in, one might ask.

Neema is the child of one of the people who serve in the Karanjai-Reynolds household. The couple has a steady stream of people hired for domestic labour and it is interesting what a range of experience these help come with. Among the reasons Reynolds offers for continuing to live in India is the relative ease with which she could outsource some of her domestic work, especially with a child like Neema to look after.

The narrative about the domestic arrangements and the people who become part of the household take up quite a chunk of the book. The cross-nation mobility of domestic workers and the sorry tales of family instability are revealing.

There are also frequent references to friends, and an endearing portrait of Reynolds’ mother, whose relationship with Neema is both deeply affectionate and unconsciously pedagogical, aiding him in developing motor skills by buying him simple toys.

Neema is the one bond between all the people who visit or work in the house. He is also the centre of much of Reynolds’ striving and it is with some pride that she closes her book as she reflects upon Neema as a young man, taking young ones suffering, like him, with autism, under his wing.

This is a straightforward memoir and it does not pretend to be high literature. It is a tale simply told of a life in which many unforeseen things are accepted with grace. There is love, and anger; there is goodness, and kindness - ordinary, yet rare.

Rosamma Thomas