4 minute read

Rags to riches is possible but comes at a cost

from 2013-05 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

The format of a self-help book tells the story of a rise from humble beginnings to untold wealth, writes

MADHUSHREE

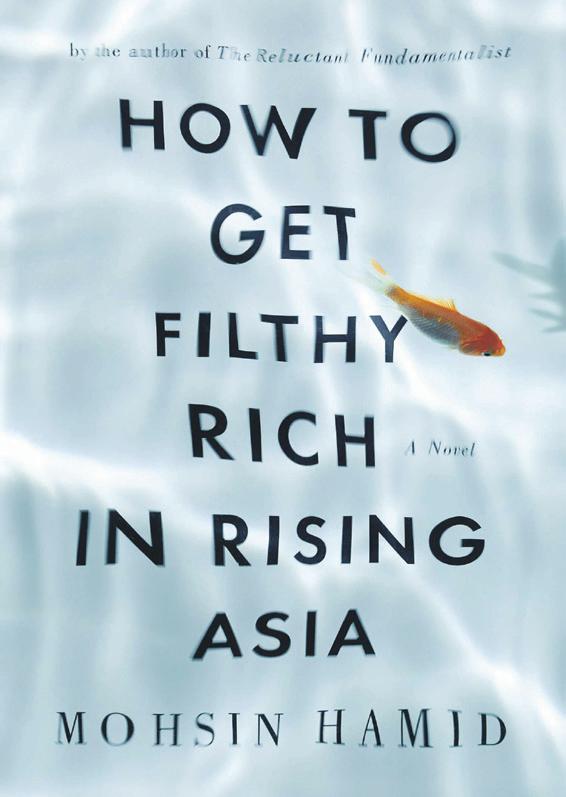

Mohsin Hamid, the Pakistanbased author of best-selling novels like the Moth’s Smoke and The Reluctant Fundamentalist, shows what it means to get rich in a rising Asia in a new novel at a time when the developing economies in the region are straining to push up their GDP figures that have been slumping all too often.

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia published by Penguin India, uses the format of the self-help and motivation book as a literary device to tell the story of the third son of a cook who leaves his village to move to a city, falls in love with a pretty girl and sets up an industry. He becomes an entrepreneur and ‘filthy rich’.

Hamid takes his hero through 12 steps, in 12 chapters to become a moneybag in a nameless city in South Asia that sizzles with energy, opportunity and inequality.

The writer says that he had initially started out with the idea that he was not going to name things and people because they mean certain things.

The idea of taking the names of the narrative, reminiscent of many avant garde writers like Lawrence Sterne, James Baldwin and James Joyce, is ‘liberating’ for Hamid.

The ingrained view is that South Asia is an ‘exotic place, a peculiar place and a central place, it is a colonial mindset’. It could have been any place, why not Lahore or Lagos? The writer explains his narrative without specifics, comparing it to the Sufi ghazals that he grew up with.

The songs invoking the nameless divine speaks to the listener or the exponent like the book that addresses the reader in a second-person narrative.

This is his third book and one inspired by the writer’s personal fortunes. “I had just become a father and I wanted to write a novel about the tri-generational life,” Hamid stated.

Generations are a way of life in

Pakistan, where young men often live with their parents and elders, like Hamid who shares his home with his parents.

The young and old play a catand-mouse waiting game.

This inter-generational divide is captured in a vivid clash of body language in a domestic confrontation between the ‘saas’ and the ‘bahu’.

“Your mother cleans the courtyard under the gaze of her mother-in-law. The old woman sits in the shadow, the edge of her shawl held in her mouth to conceal not her attributes of temptation but rather the lack of her teeth and looks on in unquenchable disapproval.

Your mother is regarded in the compound as vain, arrogant and headstrong, and these accusations have bite, for they are all true. Your grandmother tells your mother she has missed a spot. Besides, she is toothless and holds a cloth between her lips, her words sound like she is spitting... The older woman waits for the younger woman to age.”

Hamid spotlights on the society in Pakistan’s middle-class fringe with refreshing psychoanalysis of the characters. But he punctuates his narrative and observations with sage advise that tends to sound like homilies at places, flagging in their intelligence like the scores of droll motivation manuals crowding the bookshelves.

“...As far as getting rich is concerned, love can be an impediment. Yes, the pursuit of love and pursuit of wealth have much in common,” Hamid fritters in cliches, robbing pace off the narrative.

The book ends with the death of the rags-to-riches hero, surrounded by his ex-wife, son and a pretty girl that the hero had been in love with as a teen.

Hamid touches upon new South Asian realities, broken hearts, failed marriages, a culture of corruption, politics, lifestyle pressures on fast street, and the perennial near-war edge that Pakistan balances on.

The writer says his book tries to bring out a ‘narrative of loss’ in a market of growthbased language that does not equip us for loss. “Throughout history, human civilisations have been a series of narratives that talk of loss,” the writer said.

Rediscovering the bold and beautiful in Tagore

Tagore’s views through his works that reflect a modern perspective are revealed in this anthology, writes

PALOMA GANGULY

Filmmakers bring alive his stories. Rock bands experiment with his music. From poets to politicians, everyone loves to quote him. So what is it that makes Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore relevant even in the 21st century?

Perhaps a vision that was modern, yet unique. One need only delve into his novels to discover how Tagore, writing almost 100 years ago in colonial India, made bold statements on themes like women, sexuality, caste and nationalism.

He produced an astounding range of works, be it poems, plays, essays, paintings or songs. But less known is his stature as a novelist. It is this aspect of his oeuvre that academic Radha Chakravarty highlights in Novelist Tagore, published by Routledge.

At a time when the world is showing renewed interest in the bard of Bengal after his 150th birth anniversary celebrations, the book uses gender and modernity as yardsticks to discuss Tagore the novelist.

Be it Chokher Bali and The Home and the World, both of which have inspired films, or Gora, which was serialised for TV, the book takes up several stories.

We learn that Tagore’s views on gender and modernity neither conformed to Western stereotypes, nor succumbed to deep-set Indian traditions.

Consider the monumental work Gora, written in 1910. Chakravarty says it articulated the need to construct an alternative modernity that could include features of both Western and Indian culture. Set at a time when the role of women were confined to the home, Gora also recognised that any future vision of India would need to give them a decisive place in it.

Another work, Chaturanga, questioned the institution of marriage. In it, a woman enjoys conjugal bliss with a man while still in love with another, as she is free of the conventional restraints of marriage.

In Tagore’s novels, “physical desire is not condemned or rejected. In place of the conventional objectification of women as targets of male desire, his novels also present women as desiring subject,” writes the author.

Citing Nashtanir, turned into the film Charulata by Satyajit Ray, Chakravarty says in Tagore’s later writings it is “through the expression of her sexuality that woman articulates her revolt”.

Novelist Tagore may not be a book for the lay reader, as too many cross references render it as more of an academic text. But researchers, teachers and students, whom the book essentially targets, will find it of immense help.

Here’s to discovering more to the man who continues to loom over the literary and cultural firmament of Bengal, and indeed India, even 152 years after his birth.