10 minute read

The Kochi Muziri Biennale The Indian century begins now

from 2013-02 Melbourne

by Indian Link

India launched its first Biennale for Contemporary Art in Kochi on 12/12/12 and according to art critics worldwide, it has been a huge success.

BY DANIEL CONNELL

The Kochi Biennale story is one of integrity, hard work, sacrifice, leadership, determination and guts by the Biennale Foundation and a handful of political leaders who maintained a belief that India can again foster big picture inspiration and that it deserves nourishment of the newest ideas.

In 2010, the then Cultural Minister for Kerala Mr M A Baby and well-known Kerala artists Bose Krishnamachari and Ryas Komu initiated the Indian Biennale idea and succeeded enormously in pulling it off. It was affirmed in the office of the Prime Minister, and the Kochi Muziris Biennale Foundation was formed with the date set at December 12, 2012 (12/12/12).

But for the visionary leadership of these few, India’s first real contemporary art event almost would not have happened. It was plagued by baseless allegations of corruption and beset by government enquiries. When public funding was withdrawn after a change of state government, the Biennale Foundation forged on and attracted private sponsorship.

To their credit they produced a magnificent show, which the world of art is talking about. Australia too can be proud of backing a winner as out of 6 international project supporters, 3 are Australian: the Australia Council, Department of Foreign Affairs, and Trade and Asia Link.

Of the 80 artists, 6 were Australian and an additional 10 Australians were involved in satellite shows, as well as Melbourne University and the University of South Australia.

Why Kochi?

Kochi is not just interesting, but also the right choice for India’s first Biennale and Keralites should be proud. This coastal city was a thriving cosmopolitan centre for hundreds of years before Europe even knew that the East existed! Kochi has the first mosque in India, the first church and the first synagogue. It has held communities of Arabs, Chinese and Europeans alongside the dynamic Dravidians, and is the only place in India where three different European nations ruled consecutively and continuously for over 400 years. Kochi had the second elected communist government in the world and is still the most literate state in India.

A venue with character

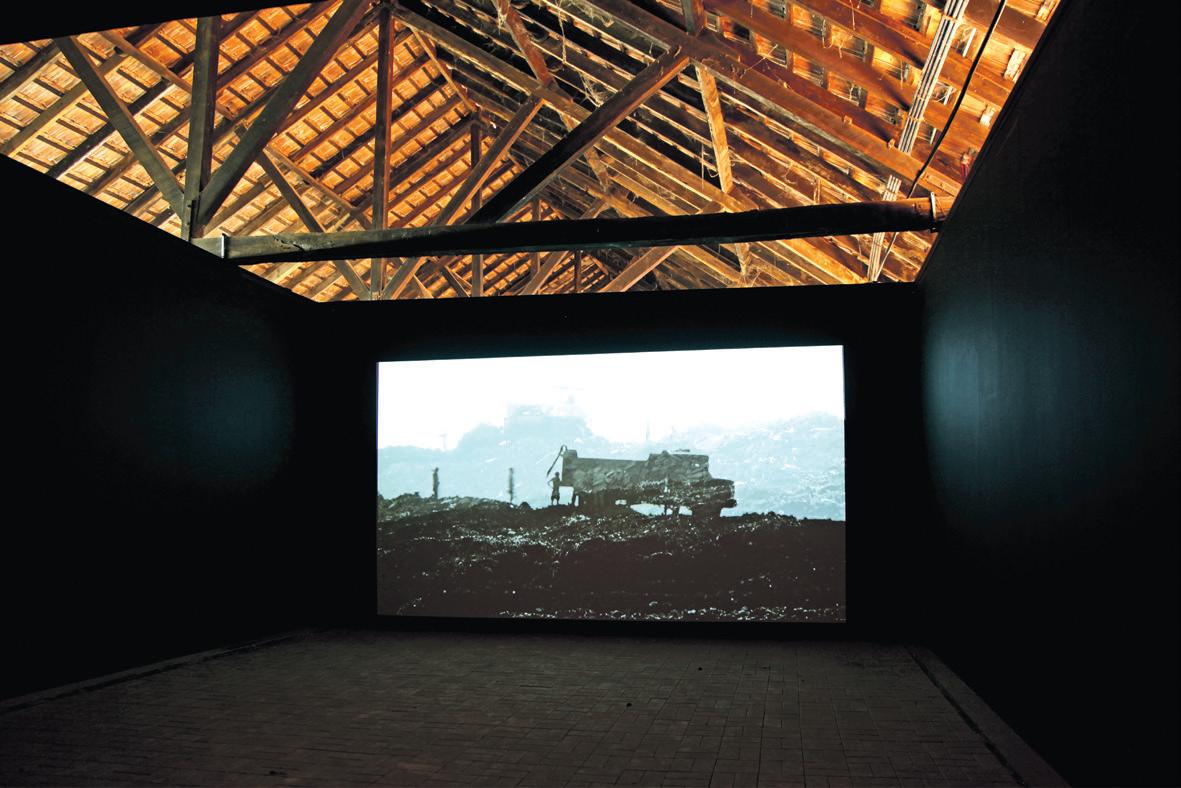

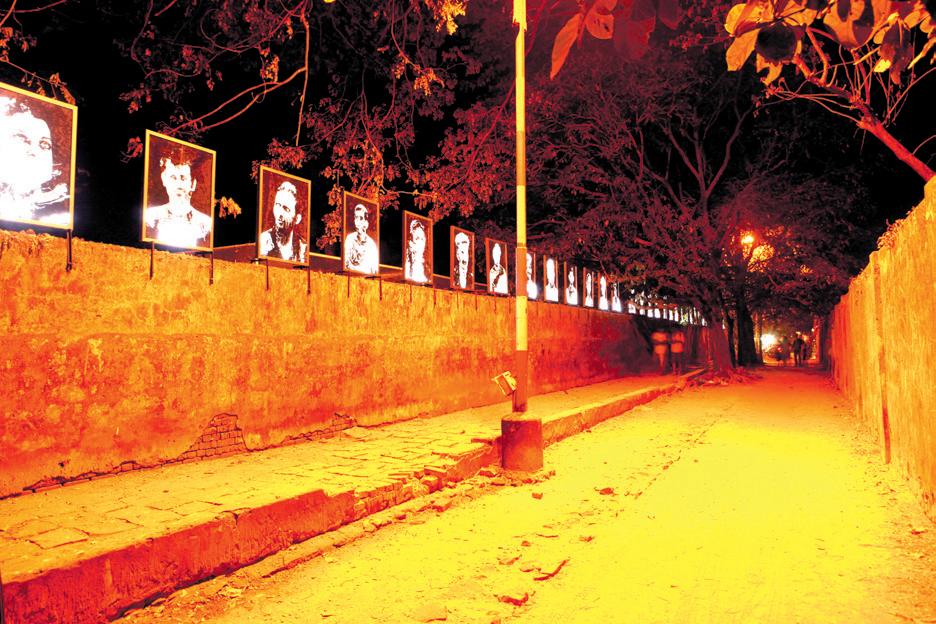

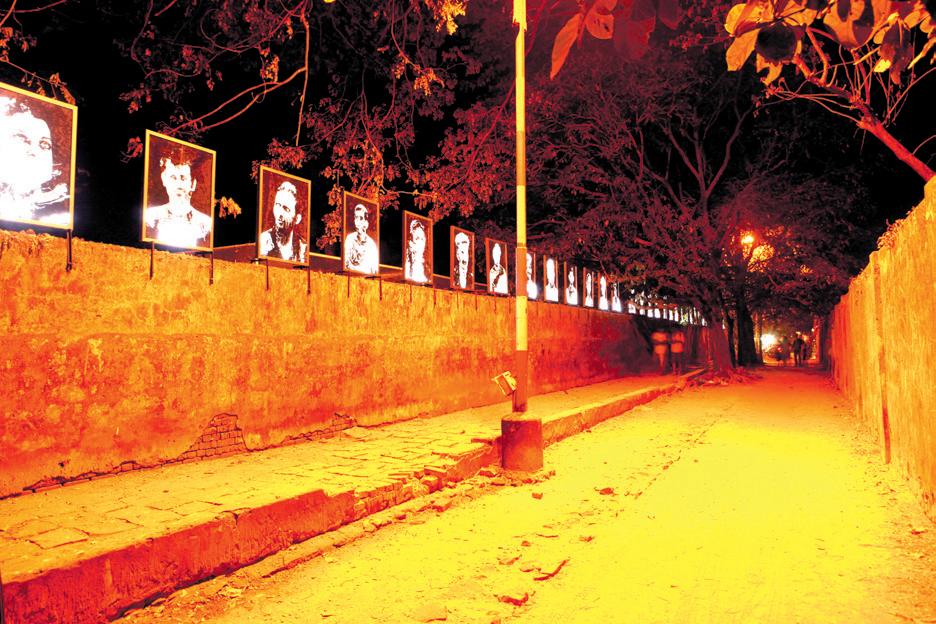

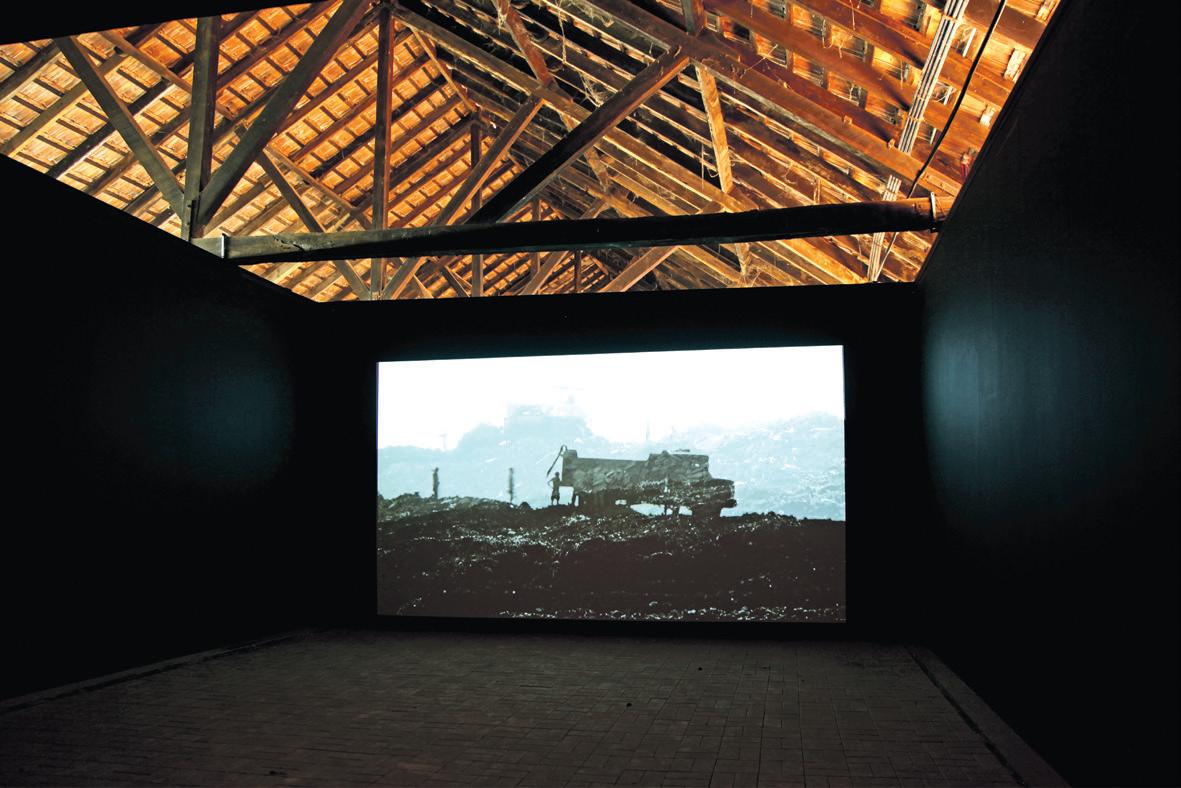

It seems that Kochi is the natural home for new ideas. The island of Fort Kochi where the Biennale is centred, offers a contained yet spacious environment to exhibit and create work, accommodate visitors and artists, all within walking distance of venues. It has a multitude of abandoned spice warehouses, lanes, walls and forgotten gardens, pungent with memory and character. The Biennale foundation has turned many into world-class art spaces. The huge Aspin Wall House, an abandoned space and coconut fibre trade house on the sea wall, is the main venue. Works are displayed in small and vast rooms, previously kitchens and offices. In pours an abundance of tropical light, and outside are immense cargo ships and wooden fishing boats so close you can touch them. It is potentially the most picturesque biennale venue in the world.

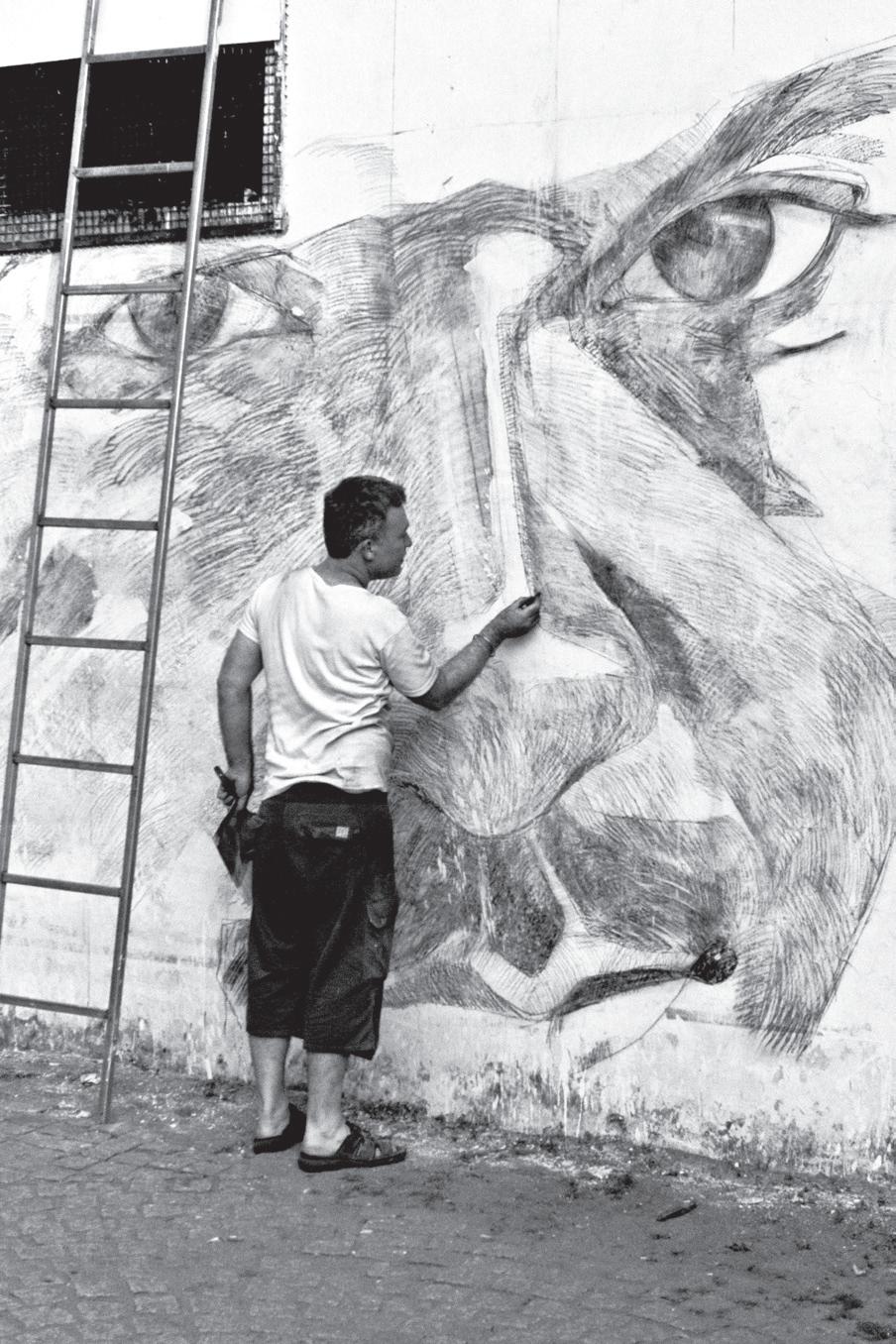

The venues, location, history combined with the sheer determination to make the event work with the raw energy of international and local artists working side by side in heat and humidity with tradesmen and labourers, all came together to create a fierce authenticity that makes the KMB a very Indian and a very new and important art experience for the world.

Behind the scenes

Some of the accusations hurled at the organisers were of elitism and exclusivism, yet I witnessed both Artistic Directors Bose and Ryas, as well as high profile members of the organising committee, attend community event after community event when no one else was looking. On one day they were welcoming the world’s most important artists to India: Ai Wei Wei, the director of Tate Modern, John Abraham or Miss India; and the next day they were

Ernesto Neto, Life is a River

at the Cochin Carnival community event with 25 local women in a small temple. No entourage, no pretence; the office is open, bustling and focussed everyday.

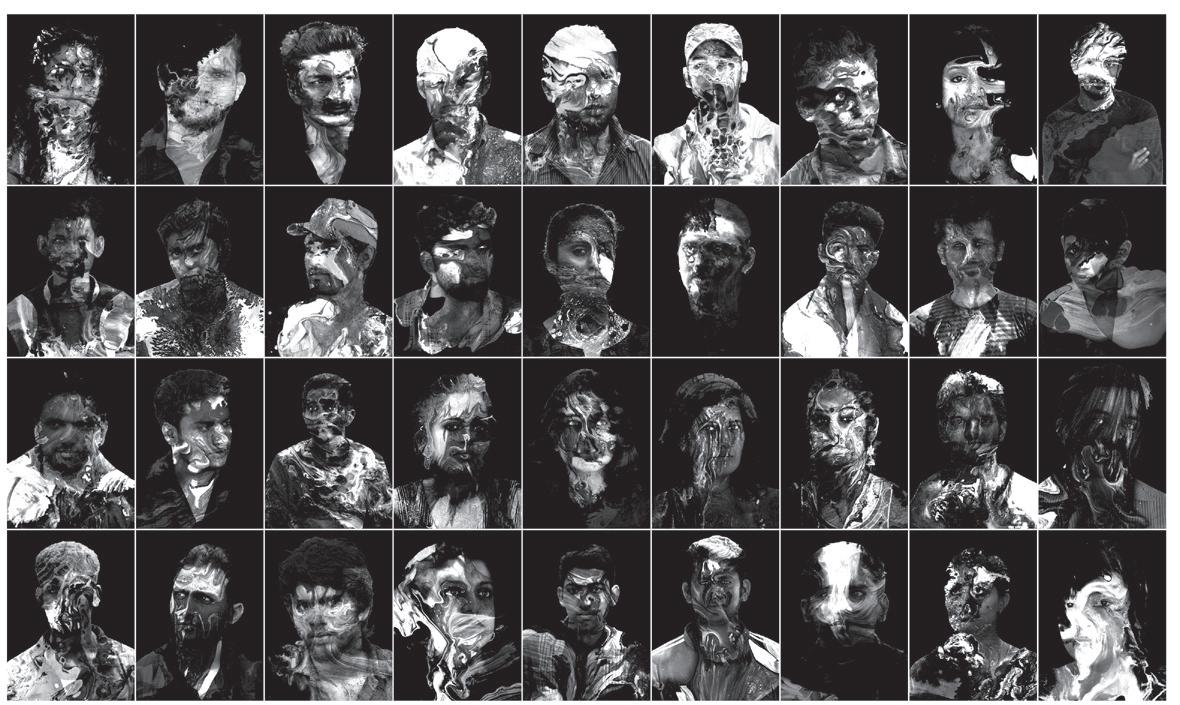

An avid audience

Most importantly however, I witnessed the rare delight of ordinary people engaging with contemporary art for the first time, and loving it. The difficult videos of Pakistani artist Rashid Rana who uses tiny moving cut squares from pornographic videos, which are inoffensive, yet somehow seductive; then there is a collage that depicts victims of a suicide bombing. In a terrible moment of recognition we are forced to link seduction and violence, forced to acknowledge a horrific familiarity. There was a policeman who spoke little English, but knew every sensitive video piece by Australian artist Angelica Mesti by heart, who showed me around Moidu’s house. I saw crowds of families reading the heart-breaking books of Amar Kanwar’s records of farmer suicides, page by page and watching open-mouthed the hidden protests against forced land accusation by villagers in Chhattisgarh. I saw auto drivers parking their 3-wheelers and coming in to see sculptures by Subodh Gupta, videos by Chinese artists and installations by South African artists. I spoke to lawyers, businessmen, students, children, housewives and unemployed labourers in exhibition halls who had favourite pieces. I saw a mum and her two teenage daughters in full Islamic dress laughing like children as they discovered a sculpture in Cabral Yard. I saw the slow drip feed of ideas seeping into the local psyche: a worker returned from Dubai who was motivated to enter one of his photos in a national competition and won; an engineer picking up his pen to write creatively after spending days in the free library of art and design in David Hall; a chai shop owner talking to the media about the value of art after his portrait drawn on a wall became the centre of a controversy. There’s talk of a side exhibition of those inspired by the Biennale at its next event.

Art liberated!

Room after room of sensitive, intelligent, gutsy, humble artworks, and I could not progress without stopping to call a friend to share the delight. After years of seeing exhibitions of paintings in Delhi and Mumbai by artists desperate to sell their work to survive, here comes this confident explosion of audacious tenacity. Art liberated! I was deeply moved by the focussed humanity that had gone into this exhibition. This event represented every potential

Biennale in the making

Over the last decade much has been spoken of the ‘boom’ in Indian art, sparked by an increase in purchasing power of the middle classes coupled with an international curiosity on how Indian artists reflected the rapid changes India was experiencing.

This boom however, was short lived. Many galleries were exploiting a new market and it could also be argued that an unsupported art infrastructure in India – museums, critics, publications, tertiary courses and events – meant that there was not sufficient depth to sustain it.

Supporters of the arts know that creative societies are prosperous ones and that a sustainable arts sector cannot happen without public and private funding for experimental art and an art-educated public. For this to happen, large public events for the visual arts are required. Over 150 cities worldwide now host Biennales. A Biennale for contemporary art is an event for which India has been crying out.

The idea of an international Indian visual art event is not new to the country. The Triennale of contemporary art spearheaded by writer Mulk Raj Anand began in 1968 under the Lalit Kala Akademi. This sadly folded and India was left in the dark.

The recent boom/bust renewed interest in the visual arts and soon the India Art Fair in Delhi originated. However, like art fairs across the world, it is an art supermarket where the price tag is often more important than the ideas within the work. Money always turns heads, but ideas are more difficult to sell; hence a Biennale, where nothing is bought nor sold but instead simply invites people to engage with ideas, was harder to get off the ground.

Visual art has the reputation of being the most avant garde of all of the art genres; a little different from performing arts and literature. It is non-conformist, but provides a richer space for ideas and is often controversial.

The lack of public or private funding for radical experimentation or conceptual art in India has forced most practicing artists either out of India or into commercial applications, such as paintings for home decoration. It has also meant that local artists have to see goodness I knew existed in the new Indian psyche. new international works on screens and rarely have a chance to view them for real.

Art is about ideas, not products. Art is a container for ideas, if you like. Ideas are the raw material for creativity. Creativity expands personal freedom and accelerates human progress, not necessarily in industry but also in relationships, understanding, inventions, design, sensitivity, health and the underlying reasons for why we do what we do. Art is an essential ingredient of a dynamic and healthy society. Art gives us not only the tools, but also the permission to think.

So if you like ideas and you love India, get to Kochi before March 13, and see India shining.

The eternal problem for artists worldwide is the tyranny of commercial galleries, that is, making what people want to buy. One antidote to this is what has become known as a ‘Biennale’, invented in Venice in1895. This is a curated exhibition happening every two years and is usually attached to a city. Biennales are expected to be the apex of avant garde, where the most complex ideas in art give a censorship-free snapshot of the current social, philosophical and political landscape from that city’s perspective. Indian artists have been well represented in international Biennales for decades, and their highly sophisticated ideas about India have been consumed by foreign audiences.

Indian audiences and Indian artists came together in a serious space to discuss reviving an interest in contemporary art, and thus was born the concept of the Kochi Muziris Biennale Foundation. Daniel Connell, an Australian visual artist who has lived and worked as an artist in India for over 5 years, spent a month at the Biennale creating new work.

Is gandhism extinct in India?

BY NOEL g DE SOUZA

Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of the Indian nation, was a complex person, like many other great people. However the thing which stands out was that he was a peaceful man, even to the point of naiveté. There has been no other such person in India’s history since its independence.

There are those who consider Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (‘mahatma’ is a title meaning ‘great soul’) to be a naïve and impractical person. For example, Gandhiji (a respectful address) believed that passive resistance by Jews against the Nazis could help them to ultimately win their rights. History has clearly proven otherwise.

President Barack Obama openly professes his admiration for Gandhi. He told students at the Wakefield High School in Arlington in 2009 that Gandhi represents the power of change through ethics, and how to use morality to foster change. Obama pointed out to the students that Gandhi made people realise that they had power within themselves and that that power needed to be used to help others, and not to oppress them.

Gandhian methods helped India gain its freedom from the British and the French which were democratic countries, but failed when it came to the Portuguese under the dictatorial rule of Salazar. Peaceful demonstrators (sathyagris) marching into Goa in 1955 were met by gunfire and mowed down. Several were killed.

During his famous speech, ‘We have a dream’ on Capitol Hill, Martin Luther King and his supporters around him wore white Gandhi caps

Gandhiji hailed from the state of Gujarat. When he moved from Britain to South Africa, he was smartly dressed and sat in a carriage reserved for whites. But though he was fair-skinned, he was thrown out of the carriage because a white person objected to his presence there. This started the Civil Rights movement in South Africa.

After returning to India, for a time Gandhiji lived in Gujarat which was known then for its Hindu-Muslim amity. In recent decades ironically, Gujarat has seen communal riots in the city of Godhra. In 2002, a railway carriage carrying activists returning from Ayodhya was set on fire, reportedly by extremist Muslims (over 30 of them were later convicted); fifty-nine persons were killed including women and children. In retaliation, Hindu activists set fire to Muslim shops and homes, resulting in over a thousand deaths. The current premier of the State has been blamed for the incident, but he denies any involvement.

Gandhiji’s methods of peaceful and nonviolent agitation secured India’s freedom from British rule. His methods worked admirably within the parameters of a democratic society. That is why Gandhian ideas of ‘passive resistance’ (called ‘satyagraha’ or action for truth, that is, for justice) have been successfully used in South Africa, the USA and Zimbabwe.

Gandhian methods helped to secure rights for Afro-Americans in the USA. Gandhi’s methods were emulated by Martin Luther King Jnr in the Civil Rights movement in the USA. During his famous speech, ‘We have a dream’ on Capitol Hill, King and his supporters around him wore white Gandhi caps. People were reminded of that speech during the Atlanta Olympic Games when images of Gandhi were prominently displayed.

In 1961, India ultimately seized control of the Portuguese possessions within India through military means. In 1975, the army overthrew the undemocratic successor to the late Salazar regime and soon after, democracy was re-established in Portugal. The country then signed a treaty recognising Indian sovereignty over its former possessions.

Today, the relationship between Portugal and India is a very friendly one. There are thousands of Indians (both Christians and Hindus) living in Lisbon where significantly, there are two statues of Gandhi in the city. There was one true follower of Gandhi who lived a selfless life. He was Acharya Vinoba Bhave, a freedom fighter who was jailed for agitating against British colonial rule in 1932. He was known in a limited circle because of his writings in his native Marathi. It was Gandhiji himself who introduced him to India in 1940.

Bhave was a spiritually minded person who had deeply studied the major Hindu texts and commented on them, as well as some on Islam and Christianity. He stated that his main purpose was the union of hearts. Bhave dedicated himself to achieving land distribution to the poor by persuading large landowners to donate land, in what became well known as the bhoodan (gift of land) movement.

Gandhiji’s utopia was an India composed of self-sufficient villages. Since then, urbanisation has skyrocketed and what were once small towns are now growing urban centres. To protect rural jobs, the government has allocated certain industries to rural areas. It is essential that jobs having mass employment be protected. Thus a machine invented to mechanise the production of a local cigarette-type item (bidi) was banned, as it would create mass rural unemployment.

In India, Gandhism is still alive in the rural sector. However, growing intolerance and vociferous activism is harming the country’s political fabric.