4 minute read

Of degradation and drugs

from 2012-04 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

Two powerful novels explore the theme of personal destruction and historical deprivation

BY CHITRA SUDARSHAN

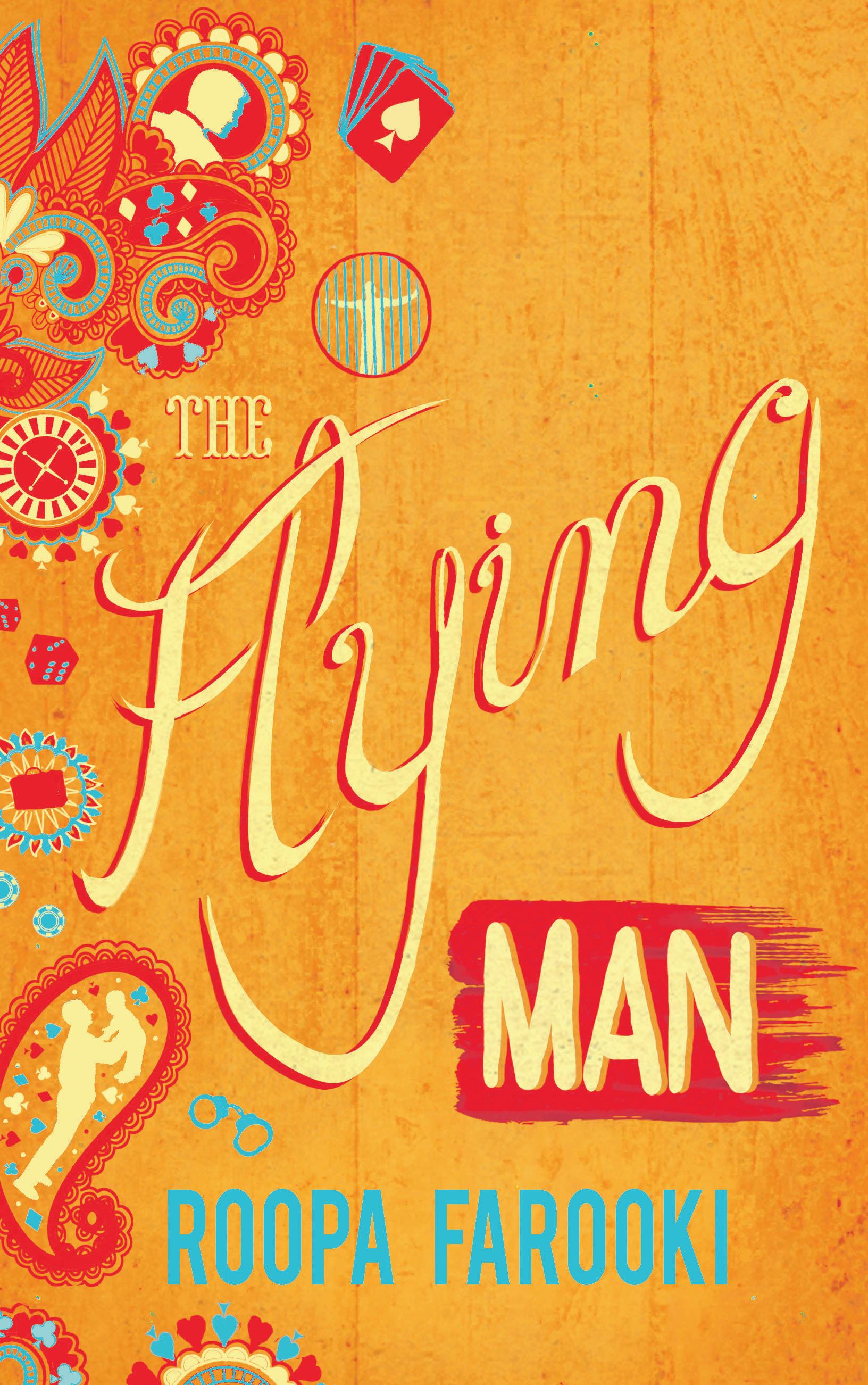

Lahore-born Roopa

Farooki has a few novels under her belt: they include Bitter Sweet, which was shortlisted for the Orange Award for New Writers in 2007 and The Way Things Look to Me, published in 2010 and longlisted for the Orange Prize last year. This was followed by Half Life soon afterwards, and her latest offering is The Flying Man Roopa’s mother is Bangladeshi and her father was from Pakistan; she moved to the UK with her parents when she was a child.

The Flying Man is the story of Maqil Karam – a figure based on the author’s own father, we learn – who is born in Lahore and educated in America, who changes his identities like a chameleon. In Cairo he is the earnest Arab ‘Mehmet’; in Paris, he is the playboy MSK. He abandons his families and responsibilities; he is a gambler and a conman who does not care much for others - and little for himself. Farooki does not romanticise or sentimentalise Maqil Karam, and he emerges more contemptible than heroic at the end of the book. But halfway into the novel just as the protagonist begins sounding banal, other characters gradually come into their own and the book begins to re-engage the reader.

Farooki’s many novels could have easily fallen into the genre of ‘chick flick’ were it not for her elegant prose and superior storytelling skills. They are both compelling and set her apart from the throng of South Asian-origin writers now populating the literary field. This is a superior novel by a truly talented writer.

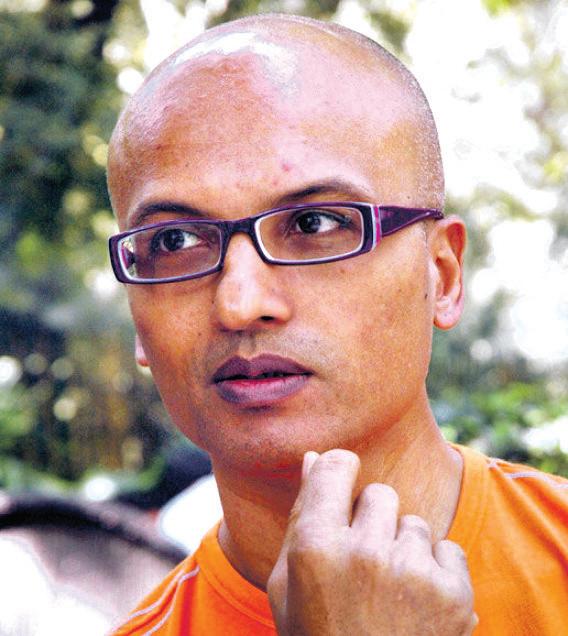

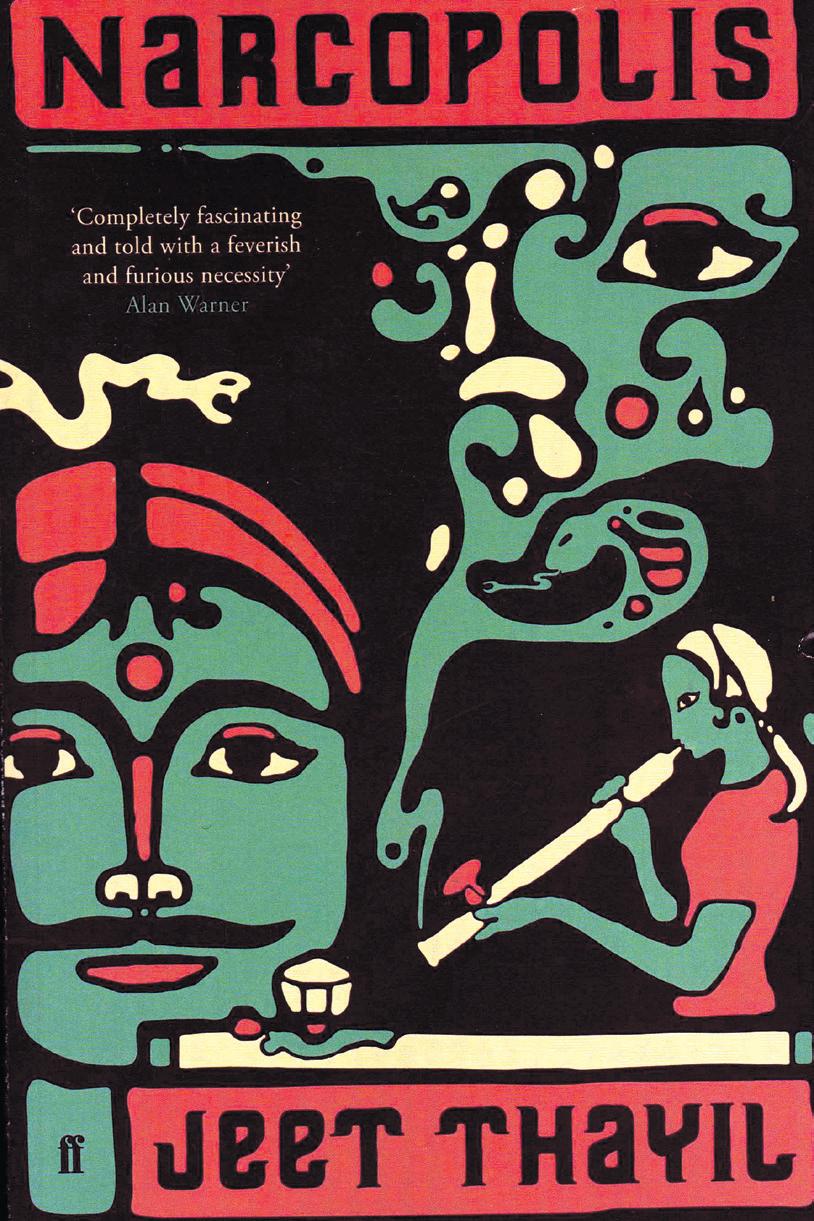

Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis is yet another novel located in Mumbai; this one however, is not your run-of-the-mill family saga. It is the Mumbai (or Bombay) of opium dens, prostitutes, drug dealers and criminals. Reading it was somewhat akin to watching Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay, only more eerie. We learn, for instance, that Mumbai was built – even before its textile mills and natural harbour – on its opium export to China; that the great Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, after whom the famous hospital and school of art are named, was a pioneer of the opium trade, as were several other prominent merchants in the city at the time!

India’s opium links with China are old. British traders got China addicted to opium grown in India, and transported it on ships owned by Indian merchants. Who said globalisation is a 21st century phenomenon? Delhi University’s Prof Amar Farooqui showed us in his brilliant essays how Mumbai owed its prosperity to opium; Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy also traced those links; Kunal Basu showed us in his novel The Opium Clerk, how his protagonist Hiran seized the opportunity provided by opium export under the British Raj, during the time preceding the Opium Wars in China. Basu located his novel in Calcutta. Thayil locates his in Shuklaji Street, Mumbai’s last connection with opium. It is the epicentre of vice and the narrator of the novel, Dom Ullis, arrives in Mumbai to take part in the trade, 150 years after it first started. He frequents Rashid’s opium den, an oldfashioned one where pipewallahs prepare the smoke for its clients. The story opens in Rashid’s opium house in the 1970s where we meet the owner himself, his regular clients and Dimple the eunuch, who prepares his pipes. Very gently, we move deeper and deeper into their lives as he portrays in vivid details the way pipes are prepared for the opium, the ambience of the opium den, and such like.

We also meet characters like Mr Lee, a former soldier from communist China who has fled that country’s cultural revolution and who gives us as sharp a portrait of it as one will ever read – and how it destroyed his parents and his girlfriend. We move onward with the years: hippies arrive and begin to appreciate the quality of Rashid’s opium; then the coming of the market liberalisation tsunami that strikes after 1991, and the whirlpool of communal riots, murder and mayhem. Thayil disaggregates the complexities, contradictions and hypocrisies of Indian life with his razor sharp but elegant prose: through his characters he portrays the emerging divisiveness of the city; the good Muslim Rashid selling heroin while complaining about brazen women; his son Jamal stares at the scantily clad women while bristling at the images of Afghanistan and Iraq and gets politicised – he might even consider becoming a suicide bomber when the time is right; the queenly beggar woman who makes the street her living room, and the Hindu praying in church, et al. He squeezes the whole world and its history into these few hundred pages of the novel. Narcopolis is a brilliant debut novel that compares with some of the best. Thayil may have lost almost 20 years of his life to addiction (as he has been quoted) but if this novel is any indication, that experience did not go to waste and we are fortunate that he came out of it and lived to write this book. He is a talented poet and librettist, and also a man of courage: he was one of the four authors who read from Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses at the Jaipur Festival in January this year, and who may now face charges for reading from a banned book.

Farooki’s many novels could have easily fallen into the genre of ‘chick flick’ were it not for her elegant prose and superior storytelling skills.

Thayil may have lost almost 20 years of his life to addiction but if this novel is any indication, that experience did not go to waste and we are fortunate that he came out of it and lived to write this book.