5 minute read

Know thy neighbour

from 2011-08 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

Despite sharing an ancient history and nation, India and Pakistan still have a largely misunderstood and mostly abrasive relationship, which shows no signs of improving

BY CHITRA SUDARSHAN

In this, India’s 64th Independence Day celebrations, one of the most serious challenges the country faces is the enigma of Pakistan. Although no one has claimed responsibility for the fourth bombing in Mumbai in 10 years and investigations are still in progress, the fact remains that India has not devised a clear, calibrated policy towards Pakistan. The scholar Sunil Khilnani cited independent India’s inability to imagine Pakistan – leave alone judge it correctly and evolve a policy to deal with it – as one of its spectacular failures. There is not enough serious study being done on Pakistan, and Indian academics have been content to rely on American research which has been skewed by the US’ own involvement in Afghanistan, both during the Cold War and now. India needs to understand Pakistan better in order to diversify its policy options; and understanding comes from serious study.

MJ Akbar attempts to do just that in his book, Tinderbox The book’s strength is its attempt to illuminate the past separation from the Hindu majority. Then came Jinnah, the liberal and lawyer committed to individual rights, with little time for religion - unless it could offer political gains. And then a late twist was provided by Maulana Maududi who died in 1979, just as General Zia-ul-Haq began to meld theology and state. and the reasons for the emergence of the idea of Pakistan. Akbar pays considerable attention to the creation of Pakistan: the idea behind it, even finding origins in mideighteenth century Muslim insecurities brought on by the Mughal decline. Out of this felt vulnerability came figures like Shah Waliullah, who initiated a move away from mystical and popular Hindu traditions across the subcontinent, and towards a virtuous polity of the pure – what Akbar calls the ‘germination of the idea of Pakistan’. After him, Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi inserted a martial interpretation into Waliullah’s ideas on jehad and waged wars across northern India in the 1820s and ’30s. Post-1857, his namesake, the modernist Syed Ahmad Khan, saw English education as the tool to free Indian Muslims from a ‘fatal shroud of complacent self-esteem’, and found a new term, i.e. ‘nations’, to press the argument for distance and

What about the future? Akbar concludes that Pakistan is in ‘danger of turning into a toxic “jelly state”, a quivering country that will neither collapse not stabilise. Hardly a reassuring thought for India; but perhaps even less reassuring is our continuing intellectual failure to take a serious look at Pakistan.

Ayesha Jalal’s book Partisans of Allah (2008) is a scholarly examination of the discourse on jihad in South Asia over 3 centuries. What Partisans makes clear is that religious discourse within Islam fluctuates widely, and is entwined with geopolitics.

Ahmed Rashid’s books recently Taliban (2010) have catapulted him to a status of one of the foremost writers on Afghanistan and Pakistan. The books chronicle the role of Pakistan’s ISI and the army in the matrix of the region’s security issues in a thoroughly candid way. Hence his recent essay “An New York Review of Books is worth taking serious notice of.

The problem in Pakistan is that the ISI/army has so far failed to express regret about the recent murders of either Bhatti or Taseer, and may have even had a role in that of the journalist Shahbaz. The army chief General Ashfaq Kayani declined to publicly condemn Taseer’s murder or even to issue a public condolence to his family. He told Western ambassadors in January in Islamabad that there were too many soldiers in the ranks who sympathise with the killer: any public statement, he hinted, could endanger the army’s unity. For decades the army and the ISI have used extremist groups to do their bidding, arming and training them to serve as proxy forces in Afghanistan and Kashmir. It is therefore not surprising that they are loath to take on the extremists.

Rashid demonstrates how the security agencies have unleashed Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the largest and most feared extremist group in Pakistan which was behind the 2008 Mumbai attacks, on to the streets of Lahore. The group has been banned by the US, Britain and the United Nations and supposedly by Pakistan too. However, they are given a free hand by the security agencies – which may have inadvertently signalled to all extremist groups, including the sectarian groups who hate Christians, that they are free to take the law into their own hands. What is behind this complex and mind-boggling strategy? It is all part of a wider cat and mouse escalation between the US and the Pakistani military. The Pakistan army/ISI want to control any future peace talks that the US may have with the Taliban, so that there is a pro-Pakistan Afghan government in Kabul. Its leaders also want to be doubly sure that any long-term American arrangements in Afghanistan do not leave India in The ISI/army may well be playing the Americans, but it does so at the cost of steadily ceding ground to the extremists. Right now, Pakistan is becoming a place where there is an army without a country. Rashid says Pakistan needs a new narrative: not the old one where the US, India and Israel are blamed for all its problems –a narrative fed and nurtured by conspiracy theories rife in the media and the public.

The Bhutto Murder Wazirstan to GHQ (2011) takes a look at the antecedents leading to the assassination of Benazir

Bhutto on December 27, 2007. It is painstakingly researched and competently put together, and full of little details that reads like a thriller. It is another useful book for those trying to make sense of Pakistan.

Other books recently published by an American and a British scholar, turn their attention to the question of whether Pakistan is a failed state or a dysfunctional one.

Anatol Lieven’s Pakistan: A Hard Country (2011) is one of them. It is obvious Lieven loves Pakistan, at times a bit too much to the extent that he glosses over the ISI’s and the Army’s often duplicitous dealings. In a nutshell, he argues that Pakistan’s network of clans and kinship is more important than anything else. Its biggest problems are water shortages/environmental degradation and population explosion (60% of its population is below 25 years old).

He is critical of the lack of realism and responsibility among even the best-educated Pakistanis, who believe that India and the United States are responsible for everything that is wrong in Pakistan. (Indeed, this reviewer remembers reading a BBC report last year: when a BBC correspondent went to the flood-ravaged regions of Pakistan after the deluge, he was told by a well educated gentleman that India was somehow behind it!) “The entire public discourse,” he says, “is rife with ludicrous conspiracy theories, many of them the work of the army itself.”

But Lieven often gets many things wrong: that Pervez M was ‘honest’; and why did the army not recognise the threat of Pakistani Taliban? He says it was because they “were not generally regarded as a serious threat”.

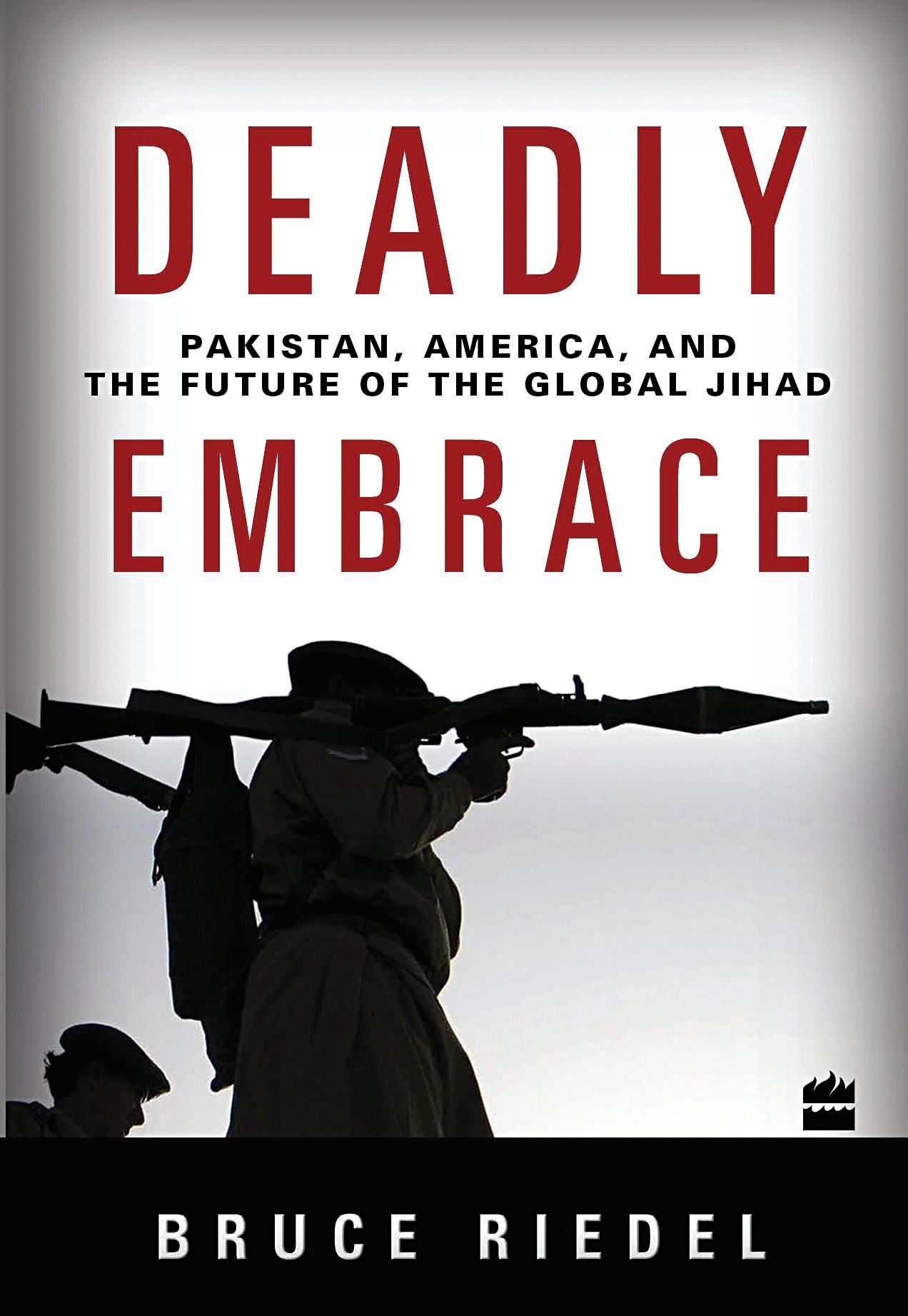

Bruce Riedel’s The Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the future of Global Jihad (2011) is another well written book on the subject. Riedel was formerly in the CIA, and involved in the administration’s Pakistan policy, so he speaks from the perspective of someone who was closely involved in US policies towards that country.

Riedel focuses on US-Pakistan relations, and offers some policy prescriptions. He urges the United States to draw two red lines with Pakistan.

The first is that Pakistan must close down all Afghan Taliban safe havens on Pakistani territory. The second is that Pakistan must shut down Lashkar-e-Taiba. Both are more easily said than done. The Afghan Taliban have now become part of the ethnic, social and political landscape in western Pakistan, and there are still some two million Afghan refugees living along the PakistanAfghanistan border. Lashkar is now perhaps 100,000 strong, a trained and armed force that cannot be dispersed easily (it was instrumental in the November 2008 Mumbai bombings). Still, all the difficulties notwithstanding, Riedel’s proposals are correct – not only for the region, but for Pakistan itself. The longer Pakistan delays, the more it will come under attack from extremists itself, as the recent assault on the Karachi naval base demonstrated. Those who grow vipers in their backyards cannot be surprised if they get bitten!