3 minute read

South Asians in politics

from 2010-08 Melbourne

by Indian Link

BY TANVEER AHMED

There is a growing presence of politicians from South Asian backgrounds in Western countries.

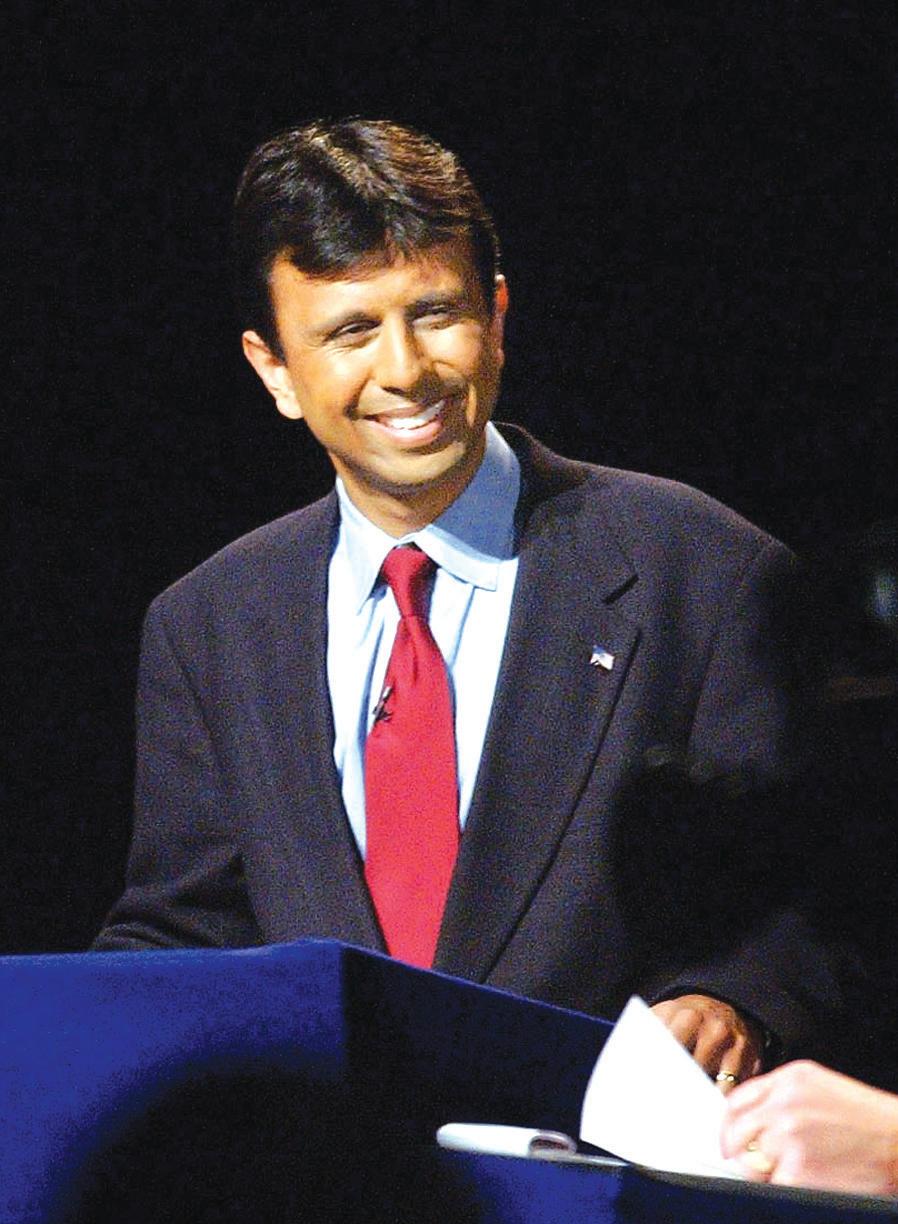

In the United States, the Governor of Louisiana, Bobby Jindal, is a regular presence on American television screens. During the current oil spill crisis, he was an even more prominent figure. The son of a doctor who studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, Jindal was touted as a potential leader of the Republican Party until he displayed an awkward performance at rebutting Obama’s first State of the Union address. But he remains the most powerful Indian politician in the world, outside India.

The Republican Nikki Haley (nee Nimrata Randhawa) will follow in his footsteps in the state of South Carolina if she wins the elections there later this year.

In the UK, the Indian-origin Keith Vaz continues to be in the limelight since he first won general elections in 1987, representing the Asian dominated constituency of Leicester, even serving a stint as Minister of State for Europe (1999-2001) in the Tony

In reality, it is unlikely that major leaders will emerge from the first generation of South Asian migrants

Blair government.

The British election held barely two months ago also thrust forward a major South Asian politician. Baroness Sayeed Warsi is a British lawyer of Pakistani descent who has long been involved in Conservative politics, before being made the chairwoman of the party and roving Minister after David Cameron ascended to the Prime Ministership. Her appointment is an affirmation of the large South Asian community in Britain.

In Canada, the glamorous Liberal Party MP Ruby Dhalla is in the news frequently, often controversially.

There are no such figures here in Australia. With another Federal election only weeks away, the prospect of any such figures arising are also very small. The number of South Asians in Australia, while significant, is smaller as a proportion of the population compared to the United States and Britain.

Nor has the period of migration been as long. Due to the White Australia policy, non-white migrants have only been arriving en masse since the 1970s, a few decades after similar migratory patterns to the Northern hemisphere were prevalent.

The majority of South Asians involved in politics in Australia are descended from the first generation of migrants, people like my own father. There are several scattered around local councils, and I remember meeting a Victorian MP of Sri Lankan background several years ago. If I can relate my observations of my father, he was heavily involved in Bangladeshi community functions and fundraisers throughout his life in Australia. It continues to be a major source of pride.

His activities often related to cultural functions where local politicians would visit to vie for the vote of their local ethnic communities. Politicians like Laurie Ferguson who live in Sydney suburbs like Auburn spend almost every night of their lives watching a cultural function from one of our countless ethnic communities. There is both beauty and drudgery in this work.

Such involvement with community organizing and contact with local politicians often propelled first generation migrants into more formal political roles, usually at a low level. There have also been a number of cases of Indian general practitioners working in rural areas who later became mayors of their country towns.

In reality, it is unlikely that major leaders will emerge from the first generation of South Asian migrants. There is a cultural interplay and social knowledge that is passed on when children are raised and educated in Australian schools that just can’t be replicated. Almost certainly, local councils will be the ceiling for this initial group of politicians.

A major exception is Dr Mukesh Haikerwal, who rose to become President of the Australian Medical Association.

So where is the next generation of politicians from our communities? To be frank, I am not so sure. While I have interacted with a number of Indians in industries like law or business who have had some involvement in politics, few have been more active. In part, they are reflecting broader trends. The second generation of immigrants are usually focussed on rising up the social and economic ladder. This is best done by being streamed into the most prestigious and highly paid jobs - like becoming a doctor, lawyer or banker. Then, as for most people, the all-encompassing task of rising up the corporate ladder, accumulating status and wealth can absorb several decades. Unless people come into contact with great injustice and become emboldened towards activism, politics is not so attractive these days. The lure of global

Afghanistan. Sri Lanka is beset with interethnic tension whose refugees are spilling over into Australia. And Bangladesh is set to become a major hotspot with regards to the effects of climate change.

Australia is a very wealthy and significant middle power. Politicians of South Asian backgrounds could be real brokers in affecting some of these pressing issues. Furthermore, broader voices from backgrounds such as this would enrich public debate within Australia and better represent the reality of diversity on the ground. It is bound to happen, but may be slower than we would like or anticipate.