3 minute read

Casteless and egalitarian?

from 2009-11 Sydney (2)

by Indian Link

NOEL G. DE SOUZA on demarcations within Australian society

Australians proudly describe their nation as being egalitarian, which according to the Macquarie Dictionary signifies “asserting the equality of all people”; this recalls the American constitutional affirmation that “all men are born equal”.

Australia is a “classless” society. When asked to elaborate, most Australians would refer to the contrast with Britain, the “Mother” country. Several scholars have shown however, by analysing income and wealth statistics, that Australia is structured into income and wealth layers and that these are effectively social classes. Class in Australia is also detectable by the manner that English is spoken. Working class English has touches of Cockney which is distinguishable from cultivated “educated English”.

Australia’s egalitarianism is founded on the existence of a large middle class – the largest income group in the country. It is common in Australia, despite the acceptance of the “classless” myth, to speak about the “middle class” and the “working class”. From whence then comes this contradiction?

The answer perhaps lies in the choice of words. Australia is not classless but rather it is casteless; Britain, like many old societies, is a caste-based society. Caste, a Portuguese word derived from the Latin castus meaning “chaste” or “pure”, refers to being “purely bred”. Castes are not a unique Indian creation as often suggested. Broadly, British castes consist of aristocrats and commoners and this has had legal connotations such as the British Parliament having an aristocratic House of Lords and, for the general population, the House of Commons.

Indian feudal society, like in Britain, had royal families, the aristocracy and the big landlords (the zamindars). Since the 19th century, as was the case in Britain, the spread of education and industrialisation have seen the beginning of a classstructured society rather than one of hereditary privileges.

Britain virtually has had two parallel societies: one is the old feudal agricultural Britain with its aristocracy which was made up of lords and the peasants who worked on their lands; the other is industrial Britain (from the 18th and 19th centuries) which had industrialists and the factory workers who worked for them. The first is a castebased society whilst the latter is a society consisting of classes dependant on income and wealth.

The House of Lords has had its aristocratic nature whittled down within the last two decades. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown has pledged that, if re-elected, he will remove the last remaining hereditary peers making the House of Lords “an accountable and democratic second chamber.” In contrast, the Australian upper house, the Senate, has always been an entirely elected body. So has India’s upper house (Rajya Sabha). In 1956, India’s princely states were merged into larger linguistic divisions. In the mid-seventies, the titles of Maharajas and other princely privileges were abolished thus moving away at least symbolically from the old feudal and caste structure towards a modern egalitarian one. Australia never had an aristocracy. Indeed, some Australians proudly trace their ancestries to convicts who had been transported from the British Isles. This might sound bizarre in Britain. Migrants coming here with aristocratic titles or caste designations may well find that these become meaningless in Australia where social class is dependant on income, wealth and other personal factors.

Several religious reformers in India sought to banish the stigma of low caste occupations but they only succeeded in establishing new sects or religions which developed their own castes though these latter were not hierarchical. Political reforms, including democracy and positive discrimination, have had much greater success in shifting people from traditional occupations to modern jobs.

Australians tend to sympathise with the most deprived persons in society such as “battlers” and the “underdogs”. In contrast to their sympathy for the “underdogs”, Australians do not have much liking for “tall poppies”. (A Tall Poppy is defined in the Australian National Dictionary as someone “whose distinction, rank, or wealth attracts envious notice or hostility”).

In the case of India, “slumdog” has become a new denigrating term following the success of the movie Slumdog Millionaire; slums exist on the peripheries of major cities of every developing country. Such slums were also common in London during the times of the author Charles Dickens who described their appalling conditions in his stories.

In the large cities in Australia, classes are reflected in the quality of the suburbs. Rich suburbs are characterised by better incomes, better health indices, less unemployment, better housing and exclusive schools. The images evoked are those of large mansions and manicured gardens. In contrast, the poorer suburbs have low income and low health indices and there is nothing exclusive about their schools. Indian cities also have lower, middle and upper class suburbs with similar disparities.

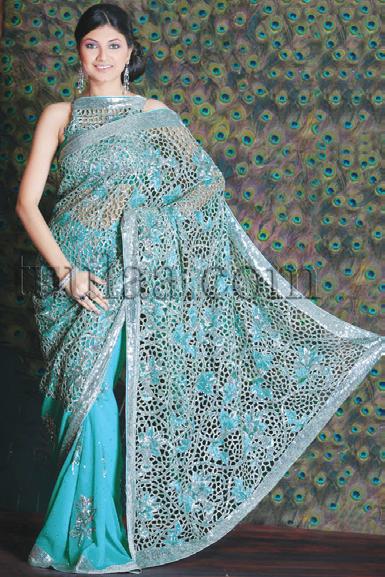

After a great success in India and Asia, www.tuulaa.com is now promoted in Australia with largest collection of Indian ethnic wear with the latest trends from bollywood crafted by designers for bollywood stars

Business opportunity with tuulaa.com (work from home and be your own boss…)

• Become a tuulaa agent with a small capital investment of AUD 5500 for stock at wholesale rate

• Select your stock yourself from tuulaa.com

• Earn great profit!

• Tuulaa brand takes care of quality, market research, pricing strategy and training for sales and fabric knowledge.

To become tuulaa agent please contact Mary (Designer of Tuulaa brand): Shop in Brisbane, 33/63 Sherwood Rd,Toowong,QLD-4066. Mary-04311 42701 (Brisbane Ofiice-07 33719607) Email: mary@tuulaa.com