NOTES FROM THE EDITOR: KAYLA SMITH

NOTES FROM THE EDITOR: KAYLA SMITH

his time of year always feels like the crescendo of life: everything building, layer upon layer, until you’re not sure whether you’re conducting a masterpiece or just trying to keep the ensemble from falling apart. The concert season is in full swing, students are juggling rehearsals and homework, and somewhere between parent emails and permission slips, the phrase “just one more run-through” starts to sound like a personal motto.

And yet, even in the dissonance of it all, there’s beauty.

As educators, we know that perseverance is part of the score. We teach our students to keep going when the notes get tricky, to breathe through the rests, and to listen (no really, listen) to those around them. It’s easy to forget we need those same reminders ourselves. When the political climate feels divided, when resources are thin, or when the stress of the season builds to cacophony, it’s our inner musician who reminds us to find balance, to slow down, and to trust that resolution will come.

Some days, perseverance looks like a flawless concert performance. Other days, it looks like surviving a middle school band rehearsal with minor emotional and equipment damage. But in all cases, it’s about showing up: baton in hand, heart in the music, doing the work that connects us to something bigger than ourselves.

I think we often underestimate the quiet kind of strength it takes to keep showing up. Perseverance isn’t always loud or heroic. Sometimes it’s just doing the next right thing. It’s the teacher who finds a creative

way to connect with a student who’s struggling. It’s the parent who shows up to the school concert after a long shift. It’s the leader who takes the time to listen when everyone is complaining.

If you’re feeling weary right now, you’re not alone. This is the season when our calendars overflow, our instruments need repair, and our sense of humor keeps us tuned. But remember: we can take our work seriously without taking ourselves too seriously. A shared laugh in rehearsal, a funny student comment, or a spontaneous dance break can do wonders for morale. After all, music is joyj, and so should be the making of it.

So as you navigate the beautiful chaos of concerts, festivals, and report cards, remember that perseverance doesn’t mean perfection. It means keeping your rhythm, even when the tempo changes. It means lifting each other up, harmonizing through the challenges, and celebrating every small success.

You’re creating something extraordinary—note by note, class by class, day by day. And in a world that sometimes feels offbeat, what you do brings harmony, connection, and hope.

So, as we push through the busy season, my hope is that you give yourself permission to breathe, to laugh, and to remember why you started doing this work in the first place. You’re making a difference, even on the days when it doesn’t feel like it. Especially on those days.

Kayla Smith Editor, INform Magazine

KEITH ZIOLKOWSKI

I hope this message finds you well as you head toward the end of your first semester.

As we look ahead to the IMEA Professional Development Conference in Fort Wayne, set for January 15–17, 2026, we are thrilled to announce that this event will officially kick off the celebration of IMEA’s 80th year as an organization! Eighty years is a profound milestone, reflecting generations of dedication to music education across Indiana.

To mark this special year, we are excited to welcome renowned keynote speaker Milton Allen. Dr. Allen will share his insights on the essential work we do, exploring topics like teaching in the age of anxiety and reaffirming why music education matters to every student we serve.

As I continue my term as President, I want to reiterate the three core goals driving our work, all of which are aligned with IMEA’s mission, vision, and strategic plan:

• Strengthen and grow our grade 6–12 Tri-M chapters.

• Enhance communication with our members and partners.

• Strengthen our board through intentional governance work.

IMEA, along with our dedicated partner organizations, is actively monitoring and engaging with critical developments within our state. This includes assessing the impact of SB1 on local governments and schools and

providing clarity on the continued rollout of the new Indiana high school diploma.

While we continue the vital work behind the scenes to seek answers, our goal is to provide our teachers with the most current resources and guidance necessary to navigate these next few years successfully. We urge you to share your feedback, whether it’s a challenge you’re facing or a success story! Please reach out to your IMEA Executive Board so we can compile and distribute these experiences to help support our community.

The dedication of our volunteers is the engine that drives IMEA’s growth and success. We recently had a few key changes. We extend our deepest gratitude to Ben Batman for his years of exceptional service on the board as our Recording Secretary. We also warmly welcome the following members who have taken on new or additional responsibilities:

• Becky Marsh – Special Learners Chair

• Alyssa Anderson – Recording Secretary

The Executive Board is continually looking to our membership for great educators willing to serve. We currently have openings for the Composition Competition Chair and the Festival and Clinic Chair. If you’re interested in getting more involved with IMEA, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me directly at president@imeamusic.org or to Alicia at office@imeamusic.org.

Warm regards,

Keith Ziolkowski President, Indiana Music Education Association

IMEA will continue to publish further details and information at https://www.imeamusic.org/

2026 Circle the State With Song Festivals

• Registration Deadline: December 10, 2025

• February 14 – Area 2, Area 3, Area 3A, Area 4, Area 5, Area 6

• February 28 – Area 1, Area 2A, Area 4A, Area 8

• March 7 - Area 7

• For more information visit: https://circlethestate.imeamusic.org

2026 IMEA Professional Development Conference

• January 15-17 in Fort Wayne

• Early Bird Registration ends December 10

• For more information visit: https://conference.imeamusic.org

2026 Folk Dance Festival

• April 25 - Greenwood Middle School

• May 2 - Mt. Vernon High School

• For more information visit: imeamusic.org/children-s-folk-dance-festival

2026 Composition Competition

• Entry deadline is June 3, 2026

• For more information visit: imeamusic.org/composition-competition

• Composition Competition Chair

• Festival & Clinic Chair

• For more information email the IMEA Office at office@imeamusic.org.

IMEA is currently looking for a Middle School coordinator (or co-coordinators) for Area 7. If you are interested or would like more information, contact State Chair Christina Huff – chuff@marion.k12.in.us.

Congratulations to the 2025 Composition Competition Gold Rating recipients! They will be recognized at the 2026 Professional Development Conference in Fort Wayne. You can view more about the recipients and listen to an excerpt of each piece by visiting https://imea.memberclicks.net/composition-competition-winners.

Cole Barlage from Zionsville West Middle School Middle School Division, Band “Variations on Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star in C Minor”

Levi Campbell from Perry Meridian High School High School Division, String Orchestra “Scraches”

Oliver Heiman from Lawrence Central High School High School Division, Full Orchestra & Jazz Band “Divination - Prédir l’avenir” & “Mischievous Heist”

Milo Savage from Fishers High School

High School Division, Instrumental Solo & String Orchestra “Double Bass Sonata” & “Song for Aspen Burns”

Matthew Raubuck from Ball State University Collegiate Division, Vocal Choir “Creations: Art and Its Creator”

UKULELE IN THE MUSIC CLASSROOM

June 8-12 | 1 Cr. | Virtual 1-4 p.m.

Lorelei Batislaong

GRANT WRITING FOR THE MUSIC EDUCATOR

June 8-11 | 1 Cr. | Virtual 5-8:45 p.m.

Ashleigh Lore

ORFF CURRICULUM

June 15-19 | 2 Cr.

Pre-req: Orff Level II

8:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m. Lisa Odom

DALCROZE EURHYTHMICS, BEGINNING & INTERMEDIATE

June 22-June 26 | 2 Cr.

8:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m.

Marla Butke & David Frego

APPLICATIONS OF WORLD MUSIC DRUMMING

June 29-July 1 | 1 Cr.

8:30 a.m.-2:30 p.m. Paul Corbiere

ORFF SCHULWERK LEVEL I & LEVEL II

July 6-17 | 3 Cr.

8:30 a.m.-4:45 p.m.

Betsy Carter, Lisa Odom, Aaron Ford, & Allison Croskey

ORFF ELEMENTAL COMPOSITION

July 13-17 | 2 Cr.

Pre-req: Orff Level II

8:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m. Josh Southard

Brochures regarding all summer offerings will be available on our website in the fall.

*ALSO OFFERING Master of Music Education Core Courses: Graduate Music Theory (Online), World Music (Online), and Bibliography & Research (On Campus) TO REGISTER OR FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT MICHELLE BADE AT: 765-717-4571 | mbade@anderson.edu | anderson.edu/summer-music

January 15-17, 2026

• Grand Wayne Convention Center

120 W. Jefferson Blvd., Fort Wayne, IN 46802

• Allen County Public Library

900 Library Plaza, Fort Wayne, IN 46802

• Courtyard by Marriott

1150 S. Harrison St., Fort Wayne, IN 46802

• Embassy Theatre

125 W. Jefferson Blvd., Fort Wayne, IN 46802

• First Presbyterian Church

300 W. Wayne St., Fort Wayne, IN 46802

• Hilton Hotel

1020 Calhoun St., Fort Wayne, IN 46802

This year’s pre-conference will feature Ruth Dwyer, Lorelei Batisla-ong, and Damon Clevenger. Ruth Dwyer will present a session title “The Ear Before the Eye”, focusing on preparing and developing the harmonic ear in grades 1-10. This session will also include a reading session incorporating how to integrate music literacy into choral reading. Lorelei Batisla-ong’s session focuses on the ukulele with her session “More Than Chords: Adding Ukulele Finger picking to the I, IV, V”. To wrap up the day, Damon Clevenger will preview of some folk dances

from the 2026 Folk Dance Festival. The workshop will take place on Thursday, January 15 from 10:00am –4:00pm EST.

We are fortunate to offer over 130 sessions and 27 concerts at this year’s conference over the course of three days. Sessions cover teaching areas such as all-interest, band, choir, general music, orchestra, and technology.

The Conference Kick-off features Keynote Speaker Dr. Milton Allen speaking on “It’s Not Okay, But We’re All Gonna Be Alright” and a performance by the Caribbean Crown Steel Band from Crown Point High School. Other featured clinicians include Andrew Himelick, Emily Maurek, Katie O’Hara LaBrie, William Sauerland, Mark Yount, and many others.

All-State Performing Ensembles

FRIDAY

• 11:00am - All-State Handbell Choir

– Nick Hanson, Clinician

• 12:00pm - All-State Jazz & Junior All-State Jazz

– Steve Sveum & Adam Waller, Clinicians

• 4:30pm – Elementary & Middle School Honor Choir

– Mariana Romero Serra & Maria Ellis, Clinicians

• 7:30pm – Intercollegiate Band

– Dennis Llinás, Clinician

SATURDAY

• 9:00am - Junior All-State Band

– Carol Brittin Chambers, Clinician

• 11:30am - All-State Orchestra

– Douglas Droste, Clinician

• 1:30pm - Honor Band

– Dr. Erica Neidlinger, Clinician

• 3:00pm - All-State Percussion

– Kevin Bobo, Clinician

• 4:00pm - Junior All-State Orchestra

– Patrick Barrett, Clinician

• 6:00pm – All-State Honor Choir

– Dr. Pearl Shangkuan, Clinician

Invited Performance Ensembles

FRIDAY

• 11:00am – Ball State University Faculty & Students

Chamber Ensemble – Yu-Fang Chen, Director

• 1:00pm – Circle City Orchestra – Elliott Lentz, Director

• 1:00pm – Indiana University Trombone Choir

– Dr. Brittany Lasch, Director

• 2:30pm – Munster High School Chorale

– Luke McGinnis, Director

• 3:30pm – Floyd Central Wind Symphony

– Scott Cooksey, Director & Jacqueline Johnson, Assistant Director

• 4:30pm – Anderson University Chorale

– Dr. Theodore Hicks, Director

• 4:30pm – University of Indianapolis Jazz Ensemble

– Mark O’Connor, Director

SATURDAY

• 9:00am – Grace College Community Wind Ensemble

– Eric Criss, Director

• 10:30am – McCulloch Jazz Choir

– Christina Huff, Director

• 10:30am – University of Evansville University Choir

– Dennis Malfatti, Director

• 11:30am – Goshen High School Wind Ensemble

– Tom Cox & Josh Kaufman, Directors

• 11:30am – Ben Davis High School Jazz 1

– Lyujohn Williams, Director

• 12:30pm – Titations

– Isaac Denniston, Director

• 1:30pm – Swing Time Big Band

– Hank Wintczak & Elvin DeBruicker, Directors

• 3:00pm – Blue Box Saxophone Quartet

– Mia Traverse, Leader

• 3:00pm – Devils Advocates

– Kyle Broady, Director

• 4:00pm – Ben Davis High School Wind Symphony

– Patrick Van Arsdale, Director

If you have any questions about the Conference, please contact the IMEA Office at office@imeamusic.org

For a full schedule of sessions and performance, download the conference app. Outside of physical performance programs, everything will be communicated via the app. The app is available on both the Apple Store and Google Play.

• Once downloaded, set up your profile.

• Search for “IMEA Events”

• Within the app, you will find a list of fellow attendees, the hour-by-hour schedule, session descriptions, information about clinicians, exhibitors, venue details, and resources.

• Participant materials related to each session will also be available in the app.

We encourage you to set up your profile and add a photo. The networking begins on the app and continues in-person at the program. We will also send periodic updates and important announcements through the conference via the app.

Register for the Conference today! The Early Bird rate ends December 10th.

The 2026 Marketplace is where attendees can visit exhibitors to learn about products, services, and partners that can benefit themselves and their classrooms. We encourage you to join us for this opportunity on-site.

Marketplace hours:

• Friday, January 16 - 10:00am-4:30pm

• Saturday, January 17 - 10:00am-3:00pm

BY STEPHEN W. PRATT, PROFESSOR OF MUSIC EMERITUS, DIRECTOR OF BANDS (RETIRED) JACOBS SCHOOL OF MUSIC, INDIANA UNIVERSITY

he tone of an ensemble is one of the most important, and yet difficult to describe, aspects of musical performance. Since it is a complex issue that is difficult to deal with, it is often neglected by conductors and players in favor of working on note correction, style, or tempo.

The conductor must first realize how much his/her physical movement affects ensemble tone. A tense conductor will produce a different ensemble tone than a more relaxed conductor. A conductor who has excellent clarity of beat will produce a different ensemble tone than one who is unclear or indecisive. A “cheer-leader” type conductor will produce a different tone than a “traffic-cop” type conductor. If we are aware of how much our physical motion and personality affects our ensemble tone, we can learn to modify ourselves, which is often necessary.

Conductors who deal with ensemble tone often divide into two camps. Some are proactive and work to produce the ensemble tone that they want. Others listen to the tone quality of the group and attempt to modify it in a reactionary way. It is a significant difference that changes the whole nature of the atmosphere of the rehearsal.

There are several things that need to be in place for those conductors who want to be proactive and work to produce a satisfying ensemble tone quality.

First, we must decide what we want. Many of the biographies of famous conductors of the past wax eloquently on the “sound” the conductor produced. We hear about the “Stokowski sound” of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Leopold Stokowski manipulated the sound effectively of many orchestras with great success. Listening to recordings, you can hear the difference Leonard Bern-

stein made with the New York Philharmonic very shortly after he became the music director. These changes were made by individuals who knew exactly the sound they wanted. We cannot think in superficial or general terms here. “I want the sound to be pretty.” “I don’t want the sound of the group to be so harsh.” Instead, we must decide exactly the tone quality we desire and then find ways to get that sound.

An aspiring conductor should listen intently to recordings and attend live performances of great ensembles to decide on a quality tonal concept to emulate. The sound of a group will be no better than the idealized sound that is in the conductor’s imagination. Once we have the sound in our head we can move forward and find ways to manipulate the tonal production of the group in a positive way.

Quality tone is based on quality fundamentals of tone production and the balance of those tones. Every rehearsal should emphasize and reinforce quality tonal concepts. For brass and woodwind players this means using enough air, having a good physical set-up and embouchure, and listening carefully to themselves and those around them as they play.

In an ensemble, it is best to first work on tone quality with unison octave exercises. Scales, arpeggios, and rhythmic etudes played with attention to listening and balance will help individual and ensemble tone. The conductor must intercede if the tone quality of the group needs attention. Every measure that is played with bad or mediocre tone quality reinforces bad or mediocre tone quality. After unison work, chorales can be effective. They are only effective, however, if the conductor is constantly listening and drawing attention to tonal production. Mere repetitive exercises can do more damage than good. Every measure played without “true listening” reinforces the act of “not listening.”

When working with repertoire, the conductor must

insist on the same tonal standards as in the warm-up period. Experienced high-level players will work to always maintain good tone quality. Inexperienced players will tend to focus on technique. It is then up to the conductor to always reinforce quality tone quality. This is true even during sight-reading sessions.

Balance is an issue best dealt with at the podium. Only the conductor, standing in front of the group, can hear all the players and make balance decisions. The conductor must be aware of the balance of bass versus middle and treble. No one wants a speaker system with lots of tweeter and not enough woofer – the recorded sound would be too brittle and harsh. If, however, there is too much woofer and not enough tweeter, the sound is muffled and without definition. Therefore, the conductor listens to the group and works with balance until the overall sound is musically satisfying. Balanced instrumentation is helpful here, but if there are too many piccolos and not enough tubas, it is still the job of the conductor to manipulate the balance to a level that Is musically satisfying.

Balance is also important within the chords produced by like-instruments. When the trumpets are playing, it

is important for the third part to be heard as well as the first part, even though it is lower, and often played by younger students. Many people suggest a ratio of balance that favors the lower parts, like a pyramid of sound. With this concept, there should be more volume in the third part, a little less in the second part and even less in the first part. In this way the low note of the chord will be heard clearly, and the high note won’t be too dominant. When this concept is applied throughout the entire ensemble, the warmth and vibrancy of the ensemble sound is enhanced.

Another important aspect of ensemble tone is the balance of melody versus accompaniment. The conductor must make sure that accompaniment parts are heard but not dominant. Melodic parts must be brought out. This leads to transparency of ensemble sound versus a “cloudy” or opaque kind of sound that makes a group musically and tonally boring. While dynamic levels come into play here, it is all relative to allowing the audience to hear what the composer wanted them to hear in a musically satisfying way.

The conductor will also want to analyze the piece to produce the tone quality that is appropriate to the

composer and the era. Every piece should not sound the same. Every piece should sound good, but appropriate to the repertoire. A chorale-based piece will have a different tone quality than a very transparent piece with light instrumentation. A work composed by a contemporary composer should likely produce a different ensemble tone than a transcription of a work from the orchestral repertoire.

When the tone quality of the ensemble is a major element of every rehearsal, there are many excellent side effects. As players listen in a more serious and comprehensive way intonation, style and precision are all improved.

Finally, we are now musicians in an era where we are surrounded by music that is generally in tune with good tone quality. Whether walking through the mall or attending a movie, people with twenty-first century ears are accustomed to unmatched standards of ensemble tone. We must do our best to produce ensembles that play with quality tone in every setting.

When I am rehearsing a group for the first time, I like to introduce them to my concepts of ensemble tone quality right away. I will usually start with scales or unison exercises the players may have in their folders, asking them, with my words, facial expression and posture, to listen very carefully to the sounds they are producing. I am very cognizant of the physical gestures I use during this time. How I present and mold my conducting gestures will influence ensemble tone quality for better or worse. My facial expression shows a seriousness of intent that should be clear to the ensemble. Warm-up time is serious, important business that should be undertaken with great care to produce good results. If I then rehearse a chorale, it is done with the same intent and with as much musical care and freedom of expression as possible. I stress taking enough air for quality tone and breathing together in a musical way. This process continues as we work on pieces in the folder.

I try to evaluate the group quickly to make major changes in balance as necessary. This often involves asking for more bass sound and less treble sound. It often also means asking for better blend in the middle parts (most often horns and saxophones). Many of our

groups simply have too many treble players and not enough bass players. At times it also means insisting on less overall volume – particularly from individual players who are accustomed to leading.

I will often ask the ensemble to play a particular chord or two to listen for balance. This will commonly mean that I will need to balance lower parts and higher parts within individual sections. We often tend to have stronger players playing higher notes, which leads to immediate balance and tonal problems that need to be adjusted. I will expect that balance issues solved in one place will carry over to other places and will listen to make sure that is the case.

I will also listen for melody/accompaniment balances. These need to be adjusted very quickly, before the players grow accustomed to drowning out that part which they have never been able to hear anyway…

This all assumes that I have studied the score and know what I want. It is my desire to go into the first rehearsal with an idealized sound in my head and then work to produce it as soon as possible.

A major part of the equation is selection of literature. Often, ensembles that play with poor tone quality are struggling with technical problems beyond their reach. Technical virtuosity on display with bad tone quality still sounds bad. It is better to select music that is reasonable in technical challenges so that proper attention can be paid to tone quality and intonation.

Great ensemble tone production is a worthy goal that is achieved through daily work. Think of it as a journey rather than a destination. Rejoice over every improvement that brings you closer to your goal. It takes tremendous dedication on the part of the conductor, but we must never give up working for improvement. It is always worth the effort.

Stephen Pratt was on the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University from 19842018 and is currently Professor of Music Emeritus. He conducted the IU Wind Ensemble at all of the major conventions and many important concert halls including Carnegie Hall. He is currently the conductor of the Southern Indiana Wind Ensemble in Bloomington.

BY JOYCE CLICK, ADJUNCT INSTRUCTOR, UNIVERSITY OF INDIANAPOLIS

Abstract: tudents with divergent learning modalities in areas such as executive functioning, mobility, emotional, and social learning bring unique strengths to our music spaces, thanks to their determination, resiliency, natural talents, and creativity. All musicians are entitled to a safe and supportive space that provides the best environment for socialization, musical growth, and collaboration.

Fifty years ago, the passage of Public Law 94-142, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), represented a pivotal moment in educational history. This legislation guaranteed that all students with disabilities were entitled to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE). As schools adjusted to this new mandate, music educators collaborated with music therapists to guide our curriculum development. Carol Bitcon, an innovator in music therapy, released her book “Alike and Different: The Clinical and Educational Uses of Orff-Schulwerk” in 1976 (Bitcon, 1976). Bitcon’s book focused on the use of chants to enhance language, the use of manipulatives such as scarves and bean bags to enhance fine motor skills, and student choice to improve engagement. Music journals featured case studies published by Paul Nordoff and Clive Robbins, describing how improvisation and composition helped children make connections with others and improve physical well-being (Nordoff & Robbins, 1977).

As our music education practice evolved, so did our federal laws guiding special education. In 1990, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The six principles of IDEA include: Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) for ages 3–21 who have identified disabilities, appropriate evaluation, an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for each student, the least restrictive environment, parent participation, and procedural safeguards. Also enacted in 1990, the

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) expanded protections beyond the classroom to all areas of public life. It prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities and ensures accessibility in facilities, employment, transportation, and communication (ADA National Network, 2024). Music educators play a critical role in supporting accessibility by ensuring performance spaces, classrooms, and resources are inclusive for all students.

How Have Music Educators Responded?

As we reflect on our inclusive practices, let us start by refining our own beliefs as music educators. Consider these questions: Does the percentage of students included in our ensembles reflect the diversity of our school, including ethnicity, gender, and students with IEPs? Is our classroom environment universally inviting to neurodiverse thinkers, students who depend on ambulatory supports, and learners who may have visual or hearing impairments? Do we collaborate with special education professionals, paraprofessionals, interventionists, and counselors to encourage students on their caseloads to consider music as an elective? Do we create an atmosphere of mutual respect with zero tolerance for derogatory and ableist language? Do we celebrate the musical growth of all our students?

As music educators, we

1. Believe that every student can develop their musical talents and actively enjoy musical experiences.

2. Intentionally create spaces where all learners are welcome, rather than those who we have determined have the apparent potential.

3. Practice lifelong learning by continuing to explore how better to serve musicians of all abilities in our music spaces.

Music educators are often high achievers and want their students to perform at the highest level. As music teachers, our plates are full, and we have limited time, energy, and resources. Our careers depend on fulfilling administrative expectations, measured by ratings, trophies, and public performances. We are balancing quality with quantity, striving

to maintain excellence while ensuring enough enrollment to sustain our programs. Music Educators can unintentionally focus primarily on advanced musicians rather than nurturing inclusivity across all ability levels

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework developed by CAST (formerly the Center for Applied Special Technology) to optimize the learning experience for all learners in our classrooms. UDL guidelines address why learners become engaged, what is learned and retained, and how students demonstrate learning. Many strategies already used in music classrooms align with UDL principles. Music educators start classes with activities that promote engagement and participation. We engage kinesthetic, social, visual, and auditory learners in varied activities.. We promote collaboration and offer flexible ways for students to demonstrate understanding. Examples include:

• Using diverse warm-ups that encourage immediate participation

• Rotating seating arrangements to promote peer interaction and leadership

• Providing visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning options.

• Allowing students to demonstrate understanding through performance, writing, or discussions

• Recording rehearsals for self-reflection and feedback

• Posting daily agenda, creating word walls, and providing large print music

• Encouraging students to share music from their culture or personal playlists, ask students to create stories about the music they are learning, and encourage students to write program notes

Differentiation tailors instruction to meet individual needs. In music classrooms, this can involve adjusting pitch levels, modifying repertoire, or incorporating visual and tactile aids. Examples include color-coding music, transposing songs, or breaking complex passages into smaller segments. Teachers can also use adapted instruments, simplify rhythms, or invite students to improvise as part of performance practice (Tomlinson, 2017). When addressing unproductive behaviors, we teach beneficial replacement alternatives and use specific, authentic praise as intrinsic reinforcement.

Inclusive music education benefits all participants by creating a culture of respect, creativity, and shared achievement. Fifty years after PL 94-142, music classrooms continue to evolve toward greater access, understanding, and joy in learning. The future of music education hinges on the belief that every learn-

• Ensembles for majors & non-majors

• Exciting concert series

Domestic & international tours

er has a place to make music actively. Every time we see a student grow musically, socially, and emotionally in our spaces, we have reason to celebrate. I fondly recall students like:

• Charles, who conquered a fluency disorder through voice lessons.

• Marc, who despite being identified as a non-reader, helped his peers learn to sight-read.

• Makayla joined the choir for social inclusion and gained enough confidence to sing a solo.

• Alec overcame his fear of speaking and became a vocal advocate for Special Olympics.

• Ellie, who, 20 years after graduation, still participates in music therapy.

As we reflect on the past successes of our inclusive music practices, let us continue to focus on student capabilities, steadfastly guiding our performers to achieve more than they ever imagined. Music classrooms that mirror the diversity of our community will flourish and bring out the inner musician in all of us.

References

ADA National Network. (2024). The Americans with Disabilities Act: An overview. https://adata.org/learn-about-ada

Bitcon, C. (1976). Alike and different: The clinical and educational uses of Orff-Schulwerk. University of Kansas Press.

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0 http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Nordoff, P., & Robbins, C. (1977). Creative music therapy: Individualized treatment for the disabled child. John Day Company.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms (3rd ed.). ASCD.

U.S. Department of Education. (2023). A guide to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

Joyce Click has spent more than four decades working with inclusive music classes in K-12 public schools. She currently serves as an Adjunct Instructor at the University of Indianapolis and Butler University in Music Education and Mild Interventions. She has authored articles for professional publications and recently published her first book with Beat by Beat Press, titled “Building a Musical Theater Program for Kids 7-14.” She was co-founder and remains an instructor of inclusive musical theater summer enrichment camps for K-12 students in Indianapolis and Music for All Abilities camps held annually at the University of Indianapolis.

BY DR. MILT ALLEN, ARTIST EDUCATOR, JUPITER INSTRUMENTS

t was 2006. A groove, CeeLo’s voice and a tune that’s rooted in a spaghetti western song called “Last Man Standing” by the Reverberi brothers (who also received credit) took the world by storm. It was Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy”. I used that tune

A LOT to introduce form, as well as how the chorus evolves to create interest. The lyrics of the tune were the result of a discussion between Danger Mouse and CeeLo Green, who make up Gnarls Barkley, about what it’s like to be a musician. Within those lyrics lies a meditation on identity, selfdoubt, and emotional unraveling, themes that mirror what countless music educators quietly experience. Listen closely, and “Crazy” becomes a mirror reflecting the mental and emotional landscape of many of us.

“I remember when, I remember, I remember when I lost my mind…”

Those opening lines strike at the heart of the music teaching profession. So many of us can recall when the joy of teaching music gave way to exhaustion — when the purpose that once fueled us began to blur under policy shifts, budget cuts, administration demands, parents, paperwork, testing mandates, covid, changing student demographics, emotional fatigue and more. The repetition of “I remember” feels like a desperate grasp at something we lost: passion, clarity, or even sanity.

“And when you’re out there without care / Yeah, I was out of touch…”

The paradox of teaching music is that you must care deeply — yet caring too much, too constantly, can push you “out of touch” with yourself. We absorb not just our students’ needs but their anxieties, their families’ expectations, and society’s ever-changing demands. In giving so much, we often lose the space to care for ourselves. The result is emotional depletion disguised as dedication. A “Crazy” form of “compassion fatigue” as the Red Cross calls it.

Then comes the chorus — “Does that make me crazy?” — a refrain that hits uncomfortably close to home. In a profession that values self-sacrifice, those who set boundaries or challenge the system can be labeled as difficult, emotional, or, indeed, “crazy.” But perhaps, as the song implies, the real insanity lies in a system that asks us to give endlessly without replenishment.

“Come on now, who do you, who do you, who do you think you are?”

That mocking question echoes the illusion of control we think we have, the belief that perfect planning or relentless effort can offset systemic dysfunction. Yet, no matter how skilled or devoted we may be, forces like poverty, trauma, and policy shifts remain beyond our reach. The laughter in that lyric isn’t just derision; it’s recognition. We’re not in control and that’s both terrifying and freeing.

“My heroes had the heart to lose their lives out on a limb…”

This lyric captures the nobility and tragedy of music education. The best of us gives ourselves completely — we risk emotional exhaustion to connect, to inspire, to make a difference. But the line carries a warning: the heart that gives everything can also break. Without self-care, reflection, and support, “heart” becomes a liability rather than a gift. Quick reminder of that great quote attributed to Henry Ford: “Givers have to set limits because takers rarely do.”

In the end, “Crazy” doesn’t resolve its tension. It leaves us wondering if “crazy” is a confession or a badge of honor. For us, maybe it’s both. Maybe “crazy” is loving your students enough to keep showing up, even when you’re stretched thin. Maybe it’s daring to care in a world that often doesn’t care back.

The lesson of “Crazy” is not about losing your mind — it’s about reclaiming it. It’s a reminder that passion without preservation leads to burnout, but awareness and authenticity lead to balance. In the end, it’s not crazy to care deeply. What’s crazy is thinking you can do it alone. REMINDER: your students are lucky to have YOU! See you at IMEA!

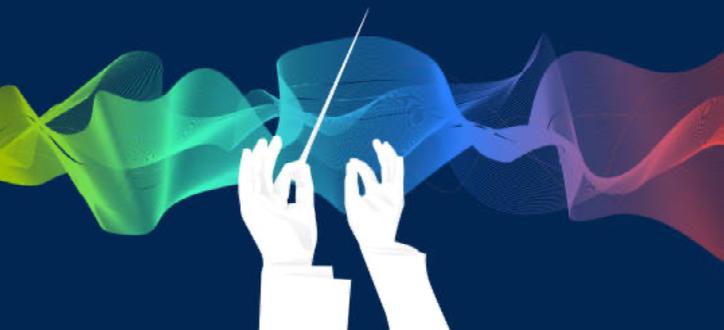

Dr. Milt Allen is an award-winning conductor, educator, and speaker whose career thrives at the intersection of music, mission, and movement. A true outlier in the field, he defies the conventional paths of music education—choosing instead to chart bold, human-centered routes that challenge, inspire, and transform.

Whether leading ensembles, speaking to educators, or trekking across continents, Dr. Allen brings fearless energy and curiosity to every endeavor. His global adventures—musical and literal—have taken him from bustling rehearsal rooms to remote corners of the world, each journey reinforcing his belief that music is a universal language of courage, connection, and change. With decades of experience as a band director, conductor, and clinician, he combines practical wisdom with unshakable passion. His sessions and stories challenge the conventional, urging musicians and educators alike to embrace the messiness of creativity, harness the power of risk, lead with empathy, and always keep learning. Of special note is his current emphasis on teacher mental health and how to thrive in an ever changing educational environment.

Milt’s work is rooted in a deep commitment to human potential whether it be via a rehearsal, keynote or a coffee conversation,

Dr. Milt Allen is living proof that music, like life, is an adventure—and everyone deserves the chance to play it boldly.

TIM COX, DIRECTOR OF EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH, MUSIC FOR ALL

ndiana’s arts and music educators have long recognized the power of creative learning to transform lives and communities. Now, as our state’s education system evolves—with high school diploma requirements shifting to emphasize workforce development—arts education stands at a pivotal crossroads. Enter the newly revamped Indiana Arts Education Network, an independent 501(c)(6) nonprofit dedicated to championing the value of music and the arts for every Hoosier student.

The Indiana Arts Education Network has relaunched with renewed purpose: building a robust coalition of educators, administrators, and community partners to ensure that the arts remain integral to every student’s education—even as state graduation pathways adapt to new economic realities.

As a 501(c)(6) organization, the Indiana Arts Education Network represents a new era of collaboration between educators, business leaders, policymakers, and community partners. The Network is designed to foster stronger connections between arts education and Indiana’s broader economic and workforce priorities. Through this work, the IAEN aims to serve as a trusted resource for helping connect ideas, share best practices, and interpret how evolving state policies impact arts education across all levels. The Indiana Arts Education Network also aspires to encourage partnerships that highlight the role of the arts in developing essential skills such as communication, collaboration, and creativity — preparing students for success in college, career, and life. At its core, IAEN seeks to be a unifying voice for arts education advocacy and advancement in Indiana — bringing together stakeholders to ensure that the arts remain an essential component of every student’s learning experience and every community’s vitality.

Indiana’s recent high school diploma changes are designed to align more closely with workforce needs—nudging academic programs toward credentials, internships, and technical skills. The Indiana Arts Education Network must respond with clarity and purpose: music and arts programs are not distractions from workforce development, but essential pipelines for the skills modern employers demand.

Research consistently links arts education with higher student engagement, lower absenteeism, and improved academic achievement. A study by the Arts Education Partnership found that students who participate in the arts are more likely to graduate high school, attend college, and be workforce-ready. The National Endowment for the Arts reports that at-risk students with high levels of arts involvement are twice as likely to graduate compared to their peers with limited access. These are outcomes that serve both individual learners and Indiana’s economy.

Today’s employers value critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and adaptability—traits cultivated every day in music rooms, studios, and theaters across the state. The arts empower students to solve problems, work as a team, and communicate ideas—skills prized from advanced manufacturing to health care to technology.

The Indiana Arts Education Network is committed to making this case, not just at the Statehouse but in every community. The Indiana Arts Education Network wants to connect arts education directly to workforce readiness, and expand the understanding of the skills learned through the arts to those who have not been involved in arts education. National initiatives like the NAMM Foundation’s Careers in Music cam-

paign underscore how arts training lays the foundation for a wide spectrum of future jobs—spanning music technology, arts administration, sound design, therapy, and beyond.

As Indiana moves forward into a new era of workforce-focused education, it’s more important than ever for music and arts educators to lift each other up and celebrate the power of the arts in every child’s life. The newly revitalized Indiana Arts Education Network warmly welcomes all performing and visual arts educators to join this growing community. Together, we can ensure the arts remain a vibrant part of every student’s education—helping shape Indiana’s future and nurturing the hearts, minds, and creativity of the whole child.

To learn more, connect with fellow advocates, or join as a member, visit https://www.inartsednetwork.org and let’s send a clear message: in Indiana, workforce readiness and a vibrant arts education go hand-in-hand.

Tim Cox works for Music for All, a National Non-Profit on the Education and Advocacy Team. He is currently the Director of Educational Outreach. He has served as Fine Arts Program Manager for the Indianapolis Public Schools where he oversaw the rebuilding of the Fine Arts programs that included purchasing $6.5 million dollars of new equipment, curriculum material, and helped to re-write the curriculum and provide guidance for the Fine Arts programs K-12. He spent 30 years in the classroom and was named MSD Decatur Township (Indianapolis) Teacher of the Year, Indiana Music Education Association High School Teacher of the Year, and one of Indiana’s Top 25 Teachers. In 2017, He was named one of the 50 Band Directors in the USA Who Make a Difference by SBO Magazine. Tim served nine years on the Indiana State School Music Association State Board and as an officer for District II of the Indiana Bandmasters Association. He is also a member of Phi Beta Mu International Bandmasters fraternity. He has been married for 32 years and has two adult children.

Bachelor of Music

● Music Education

● Music Therapy

● Music Performance

Bachelor of Science

● Music Management

● Music in Liberal Arts

Minor

● Music Studies

Music scholarships are available to outstanding students who apply and audition for the Music Conservatory.

Ensemble Participation Scholarships are available for non-Music majors who perform in a music ensemble.

For more information about the UE Music Conservatory or auditions, please call 812-488-2742 or visit music.evansville.edu

100% of rental payments apply toward rental purchase*

Enhanced premium rental fleet with upgraded cases, bows, strings, and mouthpieces

Lightning-fast shipping directly to student’s home

Award-winning service with a single point of contact

Advance-shipped exchanges limit repair downtime with the Instrument Protection Plan*

Set your music program on the right track with best-in-class instrument rentals for your new and returning students. Shop a full range of method books, instrument care supplies, reeds, mallets, sticks, music stands, and more — all backed by the best customer support in the music education world. Whether you’re directing students to instrument rentals, recommending step-up instruments to assist advancing students, or preparing your classroom from A to Z, Sweetwater has you covered!

*The terms and conditions for renting instruments on a rent-to-own basis vary depending on your state. Please carefully review the rental agreement terms and conditions for an explanation of your rights and obligations when renting an instrument on a rent-to-own basis.

**Certain maintenance and repairs may be available to rental customers at no additional cost, depending on state of residence and/or participation in the Instrument Protection Plan.