7 minute read

Feature: Pasture Perfect

Pasture Perfect

The Simple Pleasures of Regenerative Farming

By Mimi Greenwood Knight; Photos By: Reagan Moeller

When Hope Giovelli met her husband, Nick, she never dreamed they would end up living on a 60-acre farm while homeschooling their seven children.

“If someone had told me that, I think I’d have laughed at them,” Hope said.

But spending time on their Credo Farms in Amite, Louisiana, I met a couple completely content with their decisions and the contributions they are making to their community.

The first thing I saw when I visited their farm was the oldest child hard at work building a new portable chicken mobile. On a summer morning when many of his peers were zoned out in front of video games or bemoaning, “I’m booooooored,” he was wielding power tools with skill and confidence. The other kids were friendly, if a bit shy, and doing what kids should be doing on a beautiful summer day: playing outside and making memories together. Even the farm dog and cats seemed content, sleeping alongside one another in the shade.

Six years ago, when the Giovellis bought their 60 acres, it was pastureland and much of it had been fallow for years. They set about building their homestead using nature as their blueprint. As the Credo Farms website explains: "We believe that food should be clean, pure and raised with respect for the natural world. That is why we practice regenerative farming, focusing on restoring the soil, nurturing the ecosystem and producing food we can proudly put on our own table."

Regenerative farming is nothing new. In fact, it is the way farming was practiced for millennia before industrial agriculture and the idea of forcing food from the land, often to its detriment, rather than working in harmony with the land and leaving everyone, including the animals, the farmers, the local watershed and the soil itself, better for it.

The young couple toured environmentally friendly farms and read books by Joel Salatin and others who advocate a return to traditional farming practices. They started small, with Nick still working nonfarm jobs as Hope concentrated on raising the kids. Four cows turned into a herd. Six chickens turned into dozens. They practiced intensive management of the land, moving the animals daily, but otherwise allowing them to behave as nature intended.

Chickens on Credo Farms, for instance, are moved daily, which confuses predators such as owls that prefer a more stationary target.

“They live in what we call an egg mobile,” Nick explained. “We move the laying hens behind the cows. When the cows move onto fresh pasture, we move the chickens in behind them.”

The benefits of this pasture rotation are twofold. The chickens peck for the bugs they love in the cow droppings and, as they do, they distribute the manure around the field, which fertilizes the grass. That encourages a new, healthy crop for the cows to forage when they return to that pasture. Thanks to slats in the egg mobile, layer droppings add their own nutrients to enrich and rebuild the soil.

“We began farming this way because it is what we want for our own children,” Hope said. “We were surprised to realize how many others want it as much as we do.”

Credo Farms’ cows are considered “salad bar beef” because the fields they graze contain not simply grass but a variety of plants that each contribute to the flavor of the beef. Movable fencing means they are offered a new salad bar each day.

Rotational grazing also minimizes the cows’ impact on the land, allowing the grass to rest and regenerate. The result is healthier soil, happier cows, more nutrient-dense beef, and, when the chickens are added to the mix, healthier meat chickens and eggs.

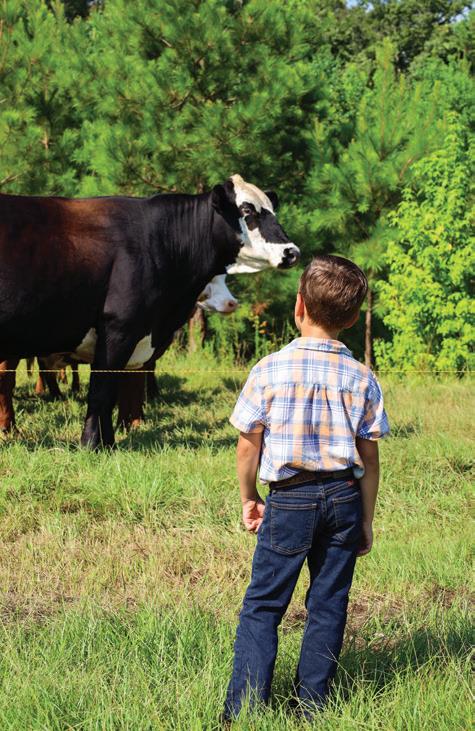

The day I visited the farm, I expected to see cows grazing on an expanse of grassland, but I did not see cows at all. We had to search for them and found them foraging within a shady stand of pines. In fact, Nick had to call to them, whistling and beating on a bucket, before they reluctantly lumbered out of the trees where we could see them. Some had huge pregnant bellies and others had newborns peeping around their legs.

The 1,000-plus-pound animals appeared calm and gentle.

“They were pretty wild when we got them,” Nick said. “But with daily moving and interaction, they have grown sweet and friendly.”

Curious, too. With their heavily lidded eyes and Pepto-pink noses, they behaved like lapdogs waiting to be scratched behind the ears.

This is the first year the Giovellis consider themselves full-time farmers.

“It took us eight years,” Hope said. (They lived on a small farm north of Covington before purchasing the Amite property.) “Farming is really a full-time job, even if you have a second job. So for years, Nick was working two full-time jobs.”

When they struggled to find hay free of chemical fertilizers, they began baling their own during the summer bounty and storing it to help the cows through the winter months. Other than that, thestruggled to find sausage seasoning that was nitrate- and MSG-free, they made their own and supplied it to the abattoir that processes their pork and beef.

“Most of what we do stems from our desire to change something in our own lives,” Hope said. “We cleaned all the chemicals and harmful ingredients from our home and started making our own soap. Then we made a batch for Christmas presents, sold the excess at the farmers market, and the business morphed into more and more and more.”

Now, Hope has her own side business on the farm. Within a metal building that is also used for chicken and egg processing, she makes handcrafted bar soaps, laundry soaps, vanilla extract and seasoning mixes featuring kelp and other beneficial minerals. All colors and scents in her soaps are derived from natural ingredients with no chemicals or synthetic constituents.

The Northshore community has responded enthusiastically to the idea of regenerative farming, snapping up Hope’s artisanal goods at the Covington farmers market, online at CredoFarms.com, and in specialty shops such as Pat’s Seafood and Clayton House, both in Covington. They also offer home delivery or farm pickup of their eggs, chicken, beef and pork, or drop-off at Springs of Life Health & Wellness Store in Covington. They are currently selling their eggs, frozen bone broth, pâté, lard and tallow at family-owned grocery stores such as Langenstein’s, Acquistapace’s at Claiborne Hill, and Dorignac’s, and sell their pastureraised chickens to restaurants.

As for homeschooling, on Credo Farms it happens as naturally as anything else.

“It is intertwined in everything we do,” Hope said. “The kids learn their letters and numbers as they help us process and price the chickens. They practice math as they count out change to customers at the farmers market.” All this hands-on application reinforces their more traditional lessons.

Also intertwined is their Christian faith. Even the name of the farm is a reflection of what the family believes.

“Credo is Latin for ‘I believe,’” Nick said. “‘Credo in unum Deum’ is our profession of faith, ‘I believe in one God.’”

“Our faith is the reason we do what we do,” Hope added. “We farm the way we feel God wants us to for our kids, our animals, our land and the customers He has given us.”

Find out more at CredoFarms.com.