17 minute read

Viewpoints

By Natalie Simonian

Pandemic PAUSE-itvies

Advertisement

In March 2020, the COVID-19 Pandemic hit its first peak in Toronto. As the government coped with the economic and social ramifications of a global pandemic, new regulations were set in place day by day. For the University of Toronto IMS graduate students, this meant that lab work was halted and students began to convert to working from home. This came with its own subset of challenges and required immense adaptation on the part of students in graduate school. There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought on a host of trials and tribulations to society as a whole and uniquely on graduate students, who for months could not enter their labs to conduct research. However, it is always important to gain perspective on any issue, and a global pandemic is no different. The media has portrayed the coronavirus as a looming dark figure that has brought nothing but harm to society, however, here I will highlight some pandemic positives as experienced by IMS graduate students.

I will begin with myself, a clinical researcher. With the restrictions on physically entering labs beginning in March 2020, I began to work from home. My days were spent on zoom calls and involved long hours of staring at a computer screen. However, as I live an hour away from campus, working from home meant that I had effectively two extra hours of my day. I began to write more short stories and poetry, a hobby that I’ve cultivated since before university. The months at home allowed me to develop a sense of direction with my poetry, draft up a manuscript, and submit this manuscript to a publishing house in Toronto. All of these efforts over the past couple of months culminated in me becoming a published author this fall and being featured in a poetry paperback book titled “You’ve Gone Incognito” that is on sale right now on TheSoapBoxPress website.

Similarly, in the same vein of cultivating hobbies, Rachel, a clinical research graduate student, expressed to me that with all her free time during the pandemic lockdown she got involved in a new hobby: growing and taking care of houseplants. She describes this hobby as therapeutic, giving her the chance to slow down and appreciate each plant and how much they grew in her care. Rachel has expressed that while devoting time to this new hobby, she has virtually met a lot of like-minded people.

A former IMS student gave me her two “silver linings from the pandemic.” Her wedding was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While this news was upsetting, the IMS alumna and her husband decided to jump-start their lives together and move in together. The first silver lining came here: she expressed that when moving in with her fiancé, she felt independent and the experience was freeing. The second silver lining was finally taking a pause and prioritizing her mental and physical health. As many of us have probably felt as graduate and post-graduate students, life at times can feel very

fast-paced, and we may forget to pause and focus on things beyond academic life. This IMS alumna exemplified the use of the lockdown to cultivate a better work-life balance as well as plan her personal life’s next steps.

The third student I spoke with, Nairy, is a commuter like myself. She lives off-campus and found it difficult to attend events, both academic and social, since they required commuting downtown. Due to the pandemic lockdown, events and clubs have become virtual. Consequently, Nairy was able to attend more events and socialize. This pandemic enriched her graduate experience by allowing her to connect with people who she probably never would have met!

The last IMS student I spoke with, Muzaffar, mentioned to me that the best thing the pandemic gave him was time. The time to create a consistent workout plan, the time to see family and friends, and the time for self-reflection. He mentioned that when the lockdown started, he struggled initially to figure out a balance between relaxing and working at home. He created a schedule and began feeling productive in more than one aspect of his life. He took the time to reflect on the activities he was doing outside of school and work and asked himself one important question which I believe we should all ask ourselves during this time of self-reflection: “Are the things that I spend my time doing meaningful to me, do I actually want to be doing these things?”. He has reorganized some of his commitments and has begun to feel more relaxed, and he now spends his nonresearch related time seeing family and friends, exercising, and acting as a TA and mentor to incoming students. must pause to acknowledge the many IMS students who have children or elders needing care living with them. Along with heath care workers, these students are the real heroes for being able to juggle research demands as well as taking care of family members during these isolating times.

When speaking with other IMS students a common shared realization emerged: the pandemic lockdown gave students the space to acknowledge and appreciate what they have in their lives and what they are thankful for. Whether it was achieving a dream, finding a new passion, advancing personal life goals, increasing social involvement, spending quality time with family members, or delving into active introspection, the pandemic “pause” gave IMS graduate students the space to figure out what is meaningful to them, what they want to prioritize in their lives and act on it.

By: Stephanie Tran

Pandemic impacts mental health in the general population

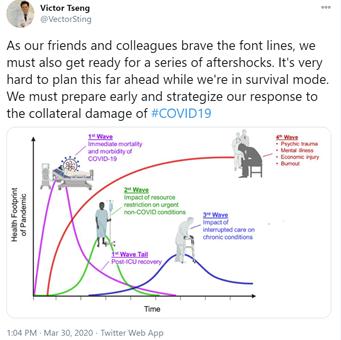

In March 2020, U.S. critical care physician Dr. Victor Tseng predicted the Covid-19 pandemic would unfold in a series of waves. Following the virus’s infectious waves, a wave of psychological trauma, mental illness, and burnout will be the pandemic’s “largest and most sustained effect”1 Half a year later, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) partnered with a research technology company, Delvinia, and conducted a series of five national surveys that supported this prediction.2 The surveys tracked mental health changes in over 1000 Englishspeaking Canadians between May and September. Over 20% of responders indicated they experienced moderate to severe anxiety and felt both lonely and depressed. Interestingly, the highest prevalence of these feelings was observed in the 18-39 age group, while the lowest was in the 60+ age group. These surveys highlight the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on mental health in young adults.

Mental health in graduate students: A crisis

Graduate students are a unique demographic. They are local experts, conducting cutting-edge research, and form the next generation of scientists, educators, leaders, and innovators. Yet, they are at risk of mental health illness.

In 2018, a study made headlines with findings that “graduate students are six times more likely to experience anxiety and depression as compared to the general population.”3 While this number has been disputed due to the lack of controls, other studies have found similarly high rates. When comparing Ph.D. students to those with higher education in the general population, Ph.D. students have a higher prevalence of mental health issues and are more likely to develop depression.4 With over 175 000 graduate students in Canada, this is creating a so-called “invisible crisis”.5

So, why are graduate students showing poor mental health? Early this year, psychologist Dr. Astrid Muller discussed this problem in an article titled, “Mental health disorders: prevalent but widely ignored in academia?”.5 She states that “the usually high workload, often associated with externally prescribed deadlines, competition for research resources, and uncertain job prospects can have an adverse impact on mental health. Problems may be aggravated by poor management practice as well as insufficient recognition and reward”. In agreement with her article, other authors note that graduate students also feel imposter syndrome, isolation, and financial stress6 , all of which can be detrimental to mental wellbeing. In a survey polling over 2000 Ontarian graduate students, nearly 70% reported that they were anxious about their degree timeline and felt pressured to overwork.7

With graduate students experiencing higher than normal mental health issues, how are they affected by the pandemic? The Toronto Science Policy Network conducted a survey to answer this question. Graduate students from 45 Canadian universities were polled between April and May.8 Of 1431 respondents, most came from the life and physical sciences. Nearly half the respondents indicated that the pandemic would impact their ability to complete their degree, and over one-quarter considered taking a leave of absence. Compared to prepandemic, concerns about finances tripled during the pandemic, with over one-third of the respondents indicating financial stress. Graduate students reported experiencing an increase in mental health issues, with 77% feeling anxious, 72% feeling overwhelmed, 76% feeling lonely and 63% feeling depressed. Overall, 72% reported that these feelings increased due to COVID-19.

Increased mental health issues in response to the pandemic have similarly been reported in graduate students worldwide. In Australia, the pandemic increased graduate students’ stress related to finances, scholarships, and the ability to meet deadlines.9 In the UK, a survey of nearly 6000 graduate students found that most students (75%) were unable to conduct their research, had poor mental wellbeing, and showed mental distress.10 While in the US, a large-sample survey found research doctoral students had the highest overall

Back in March, critical care physician Dr. Victor Tseng warned about the pandemic’s mental health “aftershocks”

prevalence of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder compared to undergraduate, master’s, and professional students.11 Compared to the 2019 survey results, graduate student depression nearly doubled, while anxiety increased by 1.5 times during the pandemic. Furthermore, the survey found the prevalence of depression and anxiety varied by field. Depression was most prevalent in the life sciences, while anxiety was most prevalent in biomedical research.

Pre-COVID-19, Nature demanded “urgent attention” for the mental health of Ph.D. researchers.12 Now, we must acknowledge that the pandemic has exaggerated the existing mental health issues in our graduate students. As these trainees go on to become experts in all sectors of the economy, ignoring the mental health crisis in this population could negatively impact future research and innovation.

Dr. Astrid Muller acknowledges a major problem with mental illness – “most people with mental disorders suffer in silence”.5 In Ontario, students refrain from discussing mental health problems for four main reasons: fear of reprisal, fear of reporting to those who are part of the problem, the uncertainty of where to seek help, and the inability to commit the time to undergo the formal complaint process.7 Many students also have an anxiety of failing or appearing weak.7 As the stigma surrounding mental health continues to exist in academia, this mental health crisis will continue to surge. Raising awareness of this mental health crisis is critical to creating an environment where mental health can be discussed openly. This movement has become widely popular on Twitter, with many academics freely discussing their graduate school and mental health problems. Students share the ups and downs of completing a degree via hashtags like #PhDLife, while accounts such as @PhD_Balance are run by and for graduate students to provide advice for improving resilience and learning through shared experience. This online platform has become a supportive community which we should strive to mirror in our institutions.

While open communication will not solve the mental health crisis, it is the first step to inducing change. Research expectations need to be adjusted to reduce anxieties related to conducting research, meeting deadlines, and degree completion, especially in these unprecedented times. Institutions need to provide more mental health support, including training for supervisors, faculty, and staff to recognize signs of distress before it escalates. It is vital to acknowledge the impact of this pandemic on the graduate student mental health crisis and to drive change to ensure that they no longer suffer in silence.

References

1. Duong, D. (2020). Doctors brace for ‘fourth wave’ of the pandemic.

Healthing.ca. https://www.healthing.ca/diseases-and-conditions/ coronavirus/doctors-brace-for-fourth-wave-of-the-pandemic 2. COVID-19 National Survey Dashboard. (2020). CAMH. https:// www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19/ covid-19-national-survey 3. Evans, T.M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J.B., Weiss, L.T., Vanderford, N.L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education.

Nature Biotechnology, 36(6), 282-284. 4. Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J,

Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in

PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868-879. 5. Muller, A. (2020). Mental health disorders: prevalent but widely ignored in academia? The Journal of Physiology, 598(7), 1729-1281. 6. Flaherty, C. (2018). A very mixed record on grad student mental health. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/ news/2018/12/06/new-research-graduate-student-mental-well-being-says-departments-have-important 7. Supporting graduate student mental health. (2017). Canadian

Federation of Students – Ontario. https://cfsontario.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2017/07/Factsheet-GraduateMentalHealth.pdf 8. COVID-19 Graduate Student Report. (2020). Toronto Science

Policy Network. https://tspn.ca/covid19-report/ 9. Woolston, C. (2020). Bleak financial outlook for PhD students in

Australia. Nature Career News. https://www.nature.com/articles/ d41586-020-02069-y 10. Byrom, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the research community: The challenges of lockdown for early-career researchers. eLife Sciences. https://elifesciences.org/articles/59634 11. Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., & Jones-White, D. (2020).

Undergraduate and graduate students’ mental health during the

COVID-19 pandemic. SERU Consortium, University of California - Berkeley and University of Minnesota. https://cshe.berkeley.edu/ seru-covid-survey-reports 12. The mental health of PhD researchers demands urgent attention. (2019). Nature, 575(7782), 257-258.

By Jason Lo Hog Tian

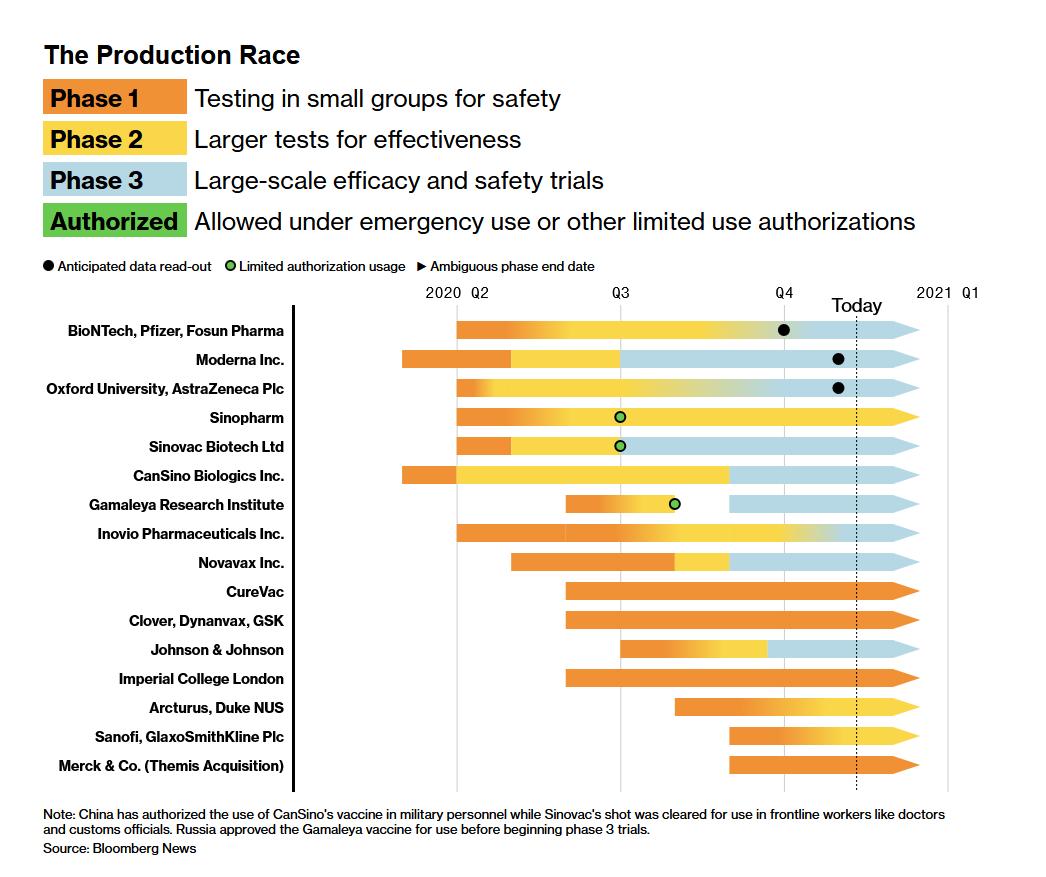

After over a year living in a different world under the COVID-19 pandemic, people are eagerly awaiting a time when they can return to normal. For most, their hopes lie in the development of a vaccine. With some vaccines in stage 3 clinical trials, many are hopeful for regulatory approval by early 2021 so we can resume our social gatherings and beach vacations. However, an approved vaccine does not mean the pandemic will be over – it is only the first hurdle. Challenges with safety, production, and distribution could mean a significant amount of time between the first vaccine approval and its widespread availability for the average person.

The purpose of a vaccine is to activate an immune response to a specific virus, resulting in long-term immunity without causing disease. When a virus enters the body, it is recognized and triggers an immune response which kills the virus as well as produces antibodies that blocks it from infecting cells and marks it for destruction.1 After being infected, the body can “remember” the virus, preventing it from causing disease if the body is re-infected and providing long-term immunity. The road to creating a vaccine is long and contains many stages, with most failing to reach final approval. Preclinical testing is the first step where vaccines are tested on animal models to see if they produce an immune response. In Phase 1, vaccines are given to a small number of people to test dosage and safety as well as to confirm if it produces an immune response. Phase 2 includes up to hundreds of people from different populations to verify safety and efficacy. Phase 3 is the last step leading to regulatory approval and involves administering the vaccine to thousands of people and examining how many get infected compared to a control group as well as identifying any rare side effects. Following the completion of Phase 3 trials, the data will be evaluated by regulating bodies and an approval decision will be made. There are many companies competing to develop the first COVID-19 vaccine with a variety of methods available to activate the immune response. Figure 1 shows the major manufacturers and their progress in the vaccine production race.2 Controversially, the vaccines developed by Gamaleya Research Institute, Sinopharm, CanSino Biologics, and Sinovac have been given emergency approval for use in Russia, United Arab Emirates, the Chinese military, and for Chinese medical workers respectively, despite not completing Phase 3 clinical trials.3 This highlights the highly political nature of COVID-19 vaccine development which may prioritize being first over being effective. Nations are in a Cold War-like arms race – the Russian vaccine is even named “Sputnik V” in a nod to the first satellite launched during the space race of the 1950’s.4 However,

many scientists have condemned such executive oversight, fearing a lack of safety and efficacy testing. Relying on Phase 1 or 2 data and skipping large-scale clinical trials means there is no concrete evidence that the vaccine is more effective than a placebo and does not give the opportunity to detect rare side effects that may not appear in a small sample. Fasttracking approval seems like an obvious step to eradicating the disease quicker, however the real winner of the “vaccine race” may not be the one who completes development first, but the one who figures out the daunting challenge of distributing it to an entire population.

If 60-70% of the world have to be immune to achieve herd immunity (when a majority of people are immune so the virus becomes difficult to spread), up to 5.6 billion people would have to be vaccinated to end the pandemic.5 At a time when infrastructure is reduced due to the pandemic itself, distributing a vaccine is going to require the largest scale up in capacity we have ever seen. This problem is made even more challenging with the conditions under which a vaccine must be kept as well as the time-sensitive nature of the product. The vaccines from Moderna Inc. and BioNTech/Pfizer/Fosun have arguably the most potential since they are RNAbased vaccines which require no culture or fermentation and can be produced rapidly. However, to keep the RNA stable it must be stored in a deep freeze, up to -80 degrees Celsius.3 This not only poses a significant problem for transportation, but for storage in pharmacies or clinics where they are most likely to be utilized. Additionally, many of the vaccines being developed may require more than one dose, doubling the burden on distribution networks and adding the extra complication of re-distributing the product to people within a strict timeframe.3 To get ahead of these problems, countries are already preordering different types of vaccine and developing the manufacturing and distribution infrastructure regardless of whether it gets approved or not, hoping to land on an effective choice. Another often unconsidered factor is that the first vaccine approved may not be the best one. While priority populations such as the elderly and healthcare workers may receive a vaccine as soon as possible, there’s no telling the length of time between the first one and the “best” one – the one you or I are more likely to receive. These are but a few of the problems that will pose a challenge to even the most industrialized countries, not to mention areas with a lack of infrastructure and healthcare services. Unfortunately, the complex task of vaccinating most of the world is likely to highlight and reinforce existing racial and socioeconomic inequalities, further extending the time it takes to achieve widespread immunity. While the end of the pandemic could not come soon enough, pushing a vaccine through the approval process is not the solution. We must uphold strict quality control standards and realize that the true battle will be delivering an effective vaccine to the entire world. It is in all our own interests to ensure equitable access to an effective COVID-19 vaccine, for the pandemic will be over not after the first vaccination, but after the last. References

1. Callaway E. The race for coronavirus vaccines: a graphical guide.

Nature. 2020;580(7805):576. 2. Flanagan C, Griffin R, Langreth R. Trial Hitches Slow Covid

Vaccine, Treatment Timeline: Bloomberg; 2020. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2020-coronavirus-drug-vaccine-status/. 3. Corum J, Grady D, Wee S-L, Zimmer C. Coronavirus vaccine tracker. The New York Times. 2020;5. 4. Mahase E. Covid-19: Russia approves vaccine without large scale testing or published results. BMJ. 2020;370:m3205. 5. Bloom BR, Nowak GJ, Orenstein W. “When Will We Have a

Vaccine?”—Understanding Questions and Answers about Covid-19

Vaccination. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020.