33 minute read

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 12

In 1956, Miller married Marilyn Monroe. The marriage didn’t last long and they divorced in 1961. He wrote the screenplay for the film The Misfits, which starred his wife shortly before their divorce. In 1962, he married the photographer Inge Morath and they had two children, Daniel and Rebecca (who later married the acclaimed actor Daniel Day-Lewis). Miller’s marriage to Morath lasted forty years until her death in 2002. In the 1960s, Miller became increasingly involved with the volatile political climate in America. He was involved in protests at various university campuses and was known for his stand against censorship and his battle for the freedom of expression.4

When he was 89, someone asked Miller what he wanted to be remembered for, he said: ‘A few good parts for actors.’ Arthur Miller died at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut on the evening of 10 February 2005, surrounded by close members of his family. More than 1 500 people attended the public memorial held in his honour at the Majestic Theatre in New York. Not everyone was able to get in. Miller had previously chosen the one word he wanted for his epitaph: ‘writer.’

Among his most popular plays are All my Sons (1947), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (1955).

Arthur Miller (Source: https://goo.gl/gRrYKs)

Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe on their wedding day. (Source: https://goo.gl/f2zhAP)

Introduction to Death of a Salesman

There was no distinct national drama in the United States until after World War I. Until that time, American theatres were full of British and Continental imports. But once established, the American theatre became a powerful force and American plays and playwrights became as familiar in England as English ones in America. The most famous trio of American playwrights include Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller and Edward Albee.

But whereas Williams concerns himself mainly with women, Miller is more focused on men, but both deal in psychological realism. Death of a Salesman has been called a modern tragedy – a story of failure, an American Dream that dissolved.5 Shortly after the play opened, Miller pointed out that ‘tragedy was not solely the prerogative of kings and princes –it could happen to the man next door, and be every bit as terrible.’

The United States has long been known as the land of opportunity. From that thinking comes the ‘American Dream’, the idea that anyone can ultimately achieve success, even if he or she began with nothing. In Death of a Salesman, we follow Willy Loman as he reviews a life of desperate pursuit of a dream of success. In this classic drama, the playwright suggests to his audience both what is truthful and what is illusory in the American Dream and, ultimately, in the lives of millions of Americans. America worships a success story; here is the reverse, raising questions of inadequacy – the fault of the little man or of society at large? The play is a powerful and disturbing piece of theatre.

About writing the play, Miller says, ‘I wished to create a form which, in itself as a form, would literally be the process of Willy Loman’s way of mind.’ To accomplish this, Miller uses the sense of time on stage in an unconventional way to illustrate that, for Willy Loman, ‘… the voice of the past is no longer distant but quite as loud as the voice of the present.’ Although he denies any direct intent to make a political statement about the capitalist way of life in the United States, Miller brings the American Dream onto the stage for evaluation.

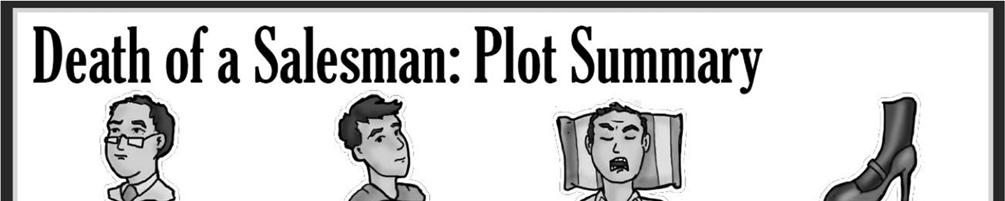

Plot summary

(Source: https://goo.gl/TPp9os)

Synopsis

Act 1

As the play opens, we are introduced to Willy Loman, a man in his early sixties, returning home, worn out from an unsuccessful attempt at driving to a business meeting. Linda, his wife, is worried and blames his inability to drive on his poor health. Willy on the other hand confesses to having strange thoughts.6 These thoughts, which are recollections of the past, will plague him throughout the play. Linda urges Willy to contact Howard Wagner (his boss) and ask for a transfer closer to home (in New York). They discuss their sons, Happy and Biff, and Linda admits that she likes the atmosphere they create in the house. The sons overhear Willy downstairs reminiscing and apprehensively discuss how unusual his behaviour is. Willy’s memories reveal how he idealised Biff, taking great pride in his athletic achievements and dismissing his weaknesses – his failure in math, his theft of the basketballs, and his cheating. His unfailing admiration towards Biff frequently ignores Happy’s need for attention. Willy even justifies Biff’s bad behaviour when Linda and Bernard (Biff’s friend next door) criticise him.

Willy boasts to Linda about his sales on his latest trip, but is quickly forced to admit that he is exaggerating, as well as revealing to his wife his self-doubt over his appearance and abilities. Linda immediately reassures him while we hear The Woman laughing, while Willy

continues to speak to his wife. The Woman dominates the conversation as it is made clear that she is his lover. Although she is never named, her presence is felt several times during the play. Weaving between the present and the past, Willy speaks of his loneliness and his inability to get ahead. The voice of the other woman flatters Willy from the past, while Linda, unaware of Willy’s daydream, tries to reassure him.

Linda begins to mend her stockings, which angers Willy as it is a guilty reminder of his betrayal and limited income. Happy goes downstairs to find out why his father has come home and what has caused all the commotion. He finds a confused Willy babbling about his wealthy brother Ben (similar to The Woman, Ben is only ever heard and seen by Willy). Ben exists in Willy’s mind as a symbol of adventure, quick success and wealth. When Willy is upset, he talks to Ben. Willy is so involved in his daydreams that Happy gives up trying to talk to his father and goes back to his room.

Bernard’s father, Charley, who lives next door, overhears Willy and goes to visit him to have a game of cards. Willy’s distress is evident when he addresses both Charley and Ben in conversation. Supportively, Charley offers Willy a job which is immediately refused. Slipping deeper into his reverie, Willy ignores Charley, and remembers Ben’s visit where his brother told him of his great success. To try and compete, Willy shows off his sons and encourages Biff to steal sand to rebuild the front step. Willy and Ben are highly amused by Linda and Charley’s worries of Biff being caught. Willy is thrown back to reality when Linda stops him from leaving the house in his pyjamas.

Biff and Happy come to investigate what is going on, and Linda tells them about their financial struggle and how their father has become so worried, he has been attempting suicide. Happy curses Willy, but Willy’s optimism is heightened as he hears Biff vowing to find a job and stay at home. Happy suggests that the brothers start a sporting goods line. They plan to ask Biff’s former boss, Bill Oliver, for some financial backing. His optimism restored, Willy goes to bed while Happy and Biff marvel at how old their parents have become.

Act 2

The next morning, Willy is still optimistic and decides to ask his boss for a non-travelling job while Happy and Biff arrange a family meal to celebrate the launch of their new business. Willy’s request is unsuccessful, despite an emotional plea. Howard plays with his tape recorder, barely listening to Willy’s needs. He finally gives Willy his attention – only to fire him. Dejected, Willy again turns to Ben, who offers him a proposition. When Willy hesitates and speaks of Dave Singleman, the man who inspired Willy to become a salesman, Ben becomes impatient and fades, so Willy goes to see Charley.

Bernard is now a successful lawyer and father of two boys. Willy congratulates him and wonders why Biff never succeeded. Bernard hints that it could be connected to when Biff visited him in Boston the summer after graduation. Willy admits to Charley that he has been fired and Charley gives Willy some money and offers him a job, which he again refuses.

Biff tells Happy that he saw Bill briefly but didn’t speak as they wait in the restaurant for Willy. Biff also realises that he was never more than a shipping clerk for Bill. He remembers all the lies that his family have told one another; Happy doesn’t want to listen and flirts with a girl and arranges a double date. Later, Willy also refuses to listen to Biff. There is a call for Happy which interrupts them, sending Willy to the washroom and his mind back to the past. Willy remembers Biff’s horror at finding him in the hotel with The Woman in Boston and how soon after he gave up college. Happy and Biff leave their father in the restaurant, leaving Stanley, the waiter, to see that Willy gets home.

Linda is awaiting the boys’ return and has pieced together the events of the evening. She wants them to leave as they insist on tormenting Willy. Biff insists on seeing his father and convinces him that he does in fact love him. Willy is overjoyed and seeks Ben’s approval to his insurance scheme that will pay Biff $20 000 if he dies. Convinced his suicide will make Biff's fortune, Willy kills himself.

Requiem

Happy is angered by his father’s death and refuses to admit that his own dreams of success were as misguided as Willy’s were. Linda is both shattered and confused by his death as she always depended on Willy’s dreams. Standing over his grave, Linda tells Willy that the mortgage on their house in finally paid. They are finally free for the first time. Charley and Biff seem to understand Willy’s suicide, but for different reasons. Charley recognises that Willy was a salesman in the truest sense of the word – he sold himself until the world stopped buying. Biff understands and forgives Willy. With his father’s death, he relinquishes any further belief in his father’s dreams. Finally, at age 34, Biff is free to be himself.

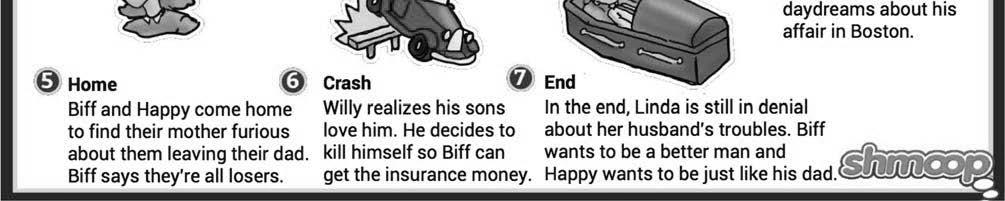

Characters

Character map of the characters in Death of a Salesman. (Source: https://goo.gl/adi3Cp)

Willy Loman ‘If Willy were merely a foolish character he would be unlikely to have earned the respect that has been paid to him. On the other hand, he is not clear sighted and does labour under delusions. He might be said to represent humanity with all its virtues and vices.’7

A 61-year-old salesman living in Brooklyn with his wife and two sons. Despite his age and the hardships he has endured, he dreams of having his own business. Willy lives by his faith in the American Dream, which he never achieves, but his dreams (however misplaced they appear) have sustained him enough to bring up his family. Willy is struggling financially, his work pays commission only and he is left wondering how he will afford the next bill. He has unrealistic ideas of his own and his family’s importance and seems egotistical when he claims his popularity with the clients. Despite his self-confidence, he lacks self-awareness, he is confused and frightened. He wants to secure his personal dignity, something that Miller relates to the depression bearing its mark on Willy. He perceives himself as a failure; he is growing old, is less productive, and truly regrets his unfaithfulness to his wife.

By nature, he is contradictory; there is a clear disparity between what he says and what he does. He is a salesman and lives by his ability to engage and make people believe him; he focuses on personal details over quantifiable measures of success believing that personality over figures garner success in the business world. Willy refuses to face reality and so appears to be living in his own world failing to distinguish between the past and the present. Nevertheless, many of Willy’s qualities are inspirational; there is a sheer courage and nobility in Willy’s struggle – especially in his refusal to give up. 8

Biff Loman ‘Biff represents Willy’s vulnerable, poetic, tragic side.’

Biff is Willy’s 34-year-old number one son. Biff led an enchanted school life, he was the star of the football team, had scholarship prospects, good friends and a following of admiring females. Biff adored his father, believed his stories and accepted his philosophy on life – that a person will be successful, providing that he is ‘well-liked’. Biff never questioned Willy, even when he was doing wrong. So unsurprisingly, Biff grew up disregarding social rules and expectations. Biff perceived Willy as the perfect father, until he discovered his affair in Boston. Biff failed math and so did not have enough credits to graduate. Since then he has had 20 to 30 jobs, every one of which he has been dismissed from. He dreams of life in the Golden West but in reality he is lost and troubled: ‘I tell ya, Hap, I don’t know what the future is. I don’t know what I’m supposed to want.’ This indecisiveness and inability to settle causes further tension between Biff and his father, but Biff has already rendered his father a ‘fake’ and despises everything he is and represents. But Biff, being his son, has inherited a few of Willy’s traits, especially his tendency to exaggerate and manipulate reality to his favour.9

Happy Loman ‘Happy represents Willy’s sense of self-importance, ambition and blind service to societal expectations.’

Happy is Willy’s 32-year-old son. He lives in his own apartment in New York, but during the course of the play he is staying at his parents’ home. All throughout childhood and into adulthood, Happy has always been in Biff’s shadow, he has always been Willy’s ‘second son’, and has become motivated to gain attention from his family by showing off. He also constantly tries to be on Willy’s good side and keep him happy, even if this does mean perpetuating the lies and illusions that Willy lives in. Happy grew up listening to his father embellish the truth, so it is not surprising that he has learnt that from Willy. Happy oozes confidence and finds seducing women easy. He believes that ‘respectable’ women cannot resist him and finds that having relationships with women is a vengeful way of getting back at the men who have surpassed him on the career ladder. He thrives on sexual gratification and the knowledge that he has ‘ruined’ so many women: ‘I hate myself for it. Because I don’t want the girl, and still, I take it and – I love it!’ Happy is of a low moral character. He is always trying to find his way in life – even when he is confident that he is on the right track. At the

end of the play, he cannot see reality, and like his father, is adamant to continue in search of the Dream.10

Linda Loman

In many ways Linda is the strongest character in the play, both emotionally and through her perseverance in supporting her husband. She is loving and loyal, acting submissively when appropriate and decisively when it matters. She is a defender of everything that Willy stands for, yet at the same time she is extremely aware of his nature. This puts Linda in an awkward situation: she knows he is irrational and difficult to deal with, yet goes along with his fantasies to protect him from self-criticism and the criticism of others. Occasionally, Linda appears to be taken in by Willy’s dreams for future success and glory, but at other times retains a sense of realism. Despite everything she knows about Willy and what he is doing, she does nothing to aggravate her husband. She supports his morale and protects him at all costs, loving him and accepting all of his shortcomings. Linda is the negotiator of peace in the family, keeping the family together and staying by Willy’s side until the end.

The 2012 Broadway Revival of Death of a Salesman’s stellar cast. From left: Finn Wittrock as Happy Loman, Linda Emond as Linda Loman, Philip Seymour Hoffman as Willy Loman and Andrew Garfield as Biff Loman. (Source: https://goo.gl/DpSMkT)

Bernard

Bernard is Biff’s cautious and studious friend, he is not as sporty or strong as the Loman brothers and Willy dismisses him as ‘not well-liked’. In many ways, Bernard possesses the opposite characteristics Biff is taught makes a man great. He helps Biff academically; he is a successful student and later becomes a successful lawyer. It feels almost as if Bernard partially fulfils the role of Biff’s dad or is present to illustrate how successful Biff could have been without Willy’s influence: ‘Just because he printed University of Virginia on his sneakers doesn’t mean they’ve got to graduate him, Uncle Willy.’ This illustrates how in tune Bernard is with reality, in comparison to the other characters. He cares for Biff and wants to see him graduate. As Bernard matures, he retains a modest, responsible and law-abiding attitude towards life; he has become a great man, without being well liked or extremely handsome.

The Woman and Miss Forsythe

The Woman is Willy’s out of town mistress. At first she makes Willy feel wanted, almost like the salesman he imagines himself being. However, she is portrayed as being rather cold and unemotional, merely seeing her encounter with Willy as being ‘good for me’. This indicates that she is there to have a good time and benefit from the affair. She picks Willy because he makes her laugh, and her laughter is heard many times throughout the play, reminding us of the frivolity and meaninglessness of what happened. Happy and Biff meet Miss Forsythe at Letta and Frank’s Chop House and she seems to be charmed by Happy’s humour. It is suggested that they are prostitutes, although Miss Forsythe claims to be a cover girl.

Charley

Charley is Bernard’s father and the closest person that Willy has to a friend. He is content with his life, a successful businessman and is an example of how you make a relative success of your life. Like his son, Charley too lacks the skills Willy associates with being masculine. He tries to make Willy face the reality of working life and is shocked at Willy’s lack of respect for him, his ideals, and his inability to distinguish reality from fantasy. Charley becomes Willy’s sole financial support and even offers Willy a job, which Willy refuses on the basis of pride.

Uncle Ben

Ben is Willy’s brother and is a symbolic figment of Willy’s imagination. Ben is self-assured, rich and adventurous, and Willy believes he is the epitome of all he desires. Ben represents his idealist view of prosperity; he is symbolic of the American Dream and of his competitive nature that allowed him to succeed in a capitalist society. Willy has imaginary conversations with Ben, where he continually misleads Willy with his talk of grandeur, success and illusions.

Howard Wagner

Howard is Willy’s boss – a successful businessman of 36 (not much older than Willy’s sons) whose sole function in the play is to tell Willy that he no longer has a job. Howard represents what Willy can expect from the average member of the business society – someone without

Charley’s kindness. He may symbolise the nature of the capitalist society. Nevertheless, he is a reasonable man who doesn’t allow emotion to affect his decision. Even at the end of the scene, Howard should not be judged too harshly, his motto being ‘business is business’.

Letta and Jenny

Letta is with Miss Forsythe when they meet Happy and Biff at Frank’s Chop House and may be comparable to The Woman who Willy meets in his hotel in Boston. Jenny is Charley’s secretary.

Stanley

Stanley is the waiter at the restaurant where Willy meets his sons. He helps Willy home after Biff and Happy leave their father there.

Themes and symbols

Define: themes

Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work. Sometimes a theme is stated explicitly, and other times it may only be implied. There is a difference between the subject and the theme of a literary work. The subject is what the playwright has chosen to write about and the theme expresses an opinion or makes a statement about the subject.

The dangers of modernity

Death of a Salesman premiered in 1949, on the brink of the 1950s, a decade of unprecedented consumerism and technical advances in America. Many innovations applied specifically to the home: it was in the 1950s that the TV and the washing machine became common household objects. Miller expresses a sort of ambivalence toward modern objects and the modern mindset. Although Willy Loman is a deeply flawed character, there is something compelling about his nostalgia. Modernity accounts for the obsolescence of Willy Loman’s career as a travelling salesman. Significantly, Willy reaches for modern objects, the car and the gas heater, to assist him in his suicide attempts.

The American Dream

Historian James Truslow Adams coined the term in his book The Epic of America in 1931. He states:

The American Dream is that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motorcars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest

stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognised by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.

Willy believes wholeheartedly in what he considers the promise of the American Dream – that a ‘well-liked’ and ‘personally attractive’ man in business will indubitably and deservedly acquire the material comforts offered by modern American life. Oddly, his fixation with the superficial qualities of attractiveness and likeability is at odds with a more gritty, more rewarding understanding of the American Dream that identifies hard work without complaint as the key to success. Willy’s interpretation of likeability is superficial – he childishly dislikes Bernard because he considers Bernard a ‘nerd’. Willy’s blind faith in his stunted version of the American Dream leads to his rapid psychological decline when he is unable to accept the disparity between the Dream and his own life.

Gender relations

In Death of a Salesman, women are sharply divided into two categories: Linda and Other. The men display a distinct Madonna-whore complex, as they are only able to classify their nurturing and virtuous mother against the other, easier women available (the woman with whom Willy has an affair as well as Miss Forsythe being only two examples). The men curse themselves for being attracted to the whore-like women. In an oedipal moment (referring to the play Oedipus Rex), Happy laments that he cannot find a woman like his mother, but is still irrepressibly drawn to them.

Women themselves are two-dimensional characters in this play. They remain firmly outside the male sphere of business, and seem to have no thoughts or desires other than those pertaining to men. Even Linda, the strongest female character, is only fixated on a reconciliation between her husband and her sons, selflessly subordinating herself to serve to assist them in their problems. Like Willy, Happy too undermines the sanctity of marriage and his conversations with Biff highlight a very sexist approach and indicate a clear lack of maturity. He refers to seducing women as being like bowling: It is easy to strike at immobile, senseless targets, and many of the women referred to seem passively waiting only for men to come into their existence and claim them.

Madness

Madness is a dangerous theme for many artists whose creativity can put them on the edge of what is socially acceptable. Madness reflects the greatest technical innovation of Death of a Salesman – it seamlessly hops backwards and forward in time. The audience or reader quickly realises, however, that this is based on Willy’s confused perspective. Willy’s madness becomes more and more of an issue as he hallucinates more and more. The reader must decide for themself how concrete a character Ben is, for example, or even how reliable the plot and narrative structure are, when told from the perspective of someone on the edge, as Willy Loman is.

Cult of personality

One of Miller’s techniques throughout the play is to familiarise certain characters by having them repeat the same key line over and over. Willy’s most common line is that businessmen

must be well liked, rather than merely liked, and his business strategy is based entirely on the idea of a cult of personality.

He believes that it is not what a person is able to accomplish, but who he knows and how he treats them that will get a man ahead in the world. His sons, who assumed that they could make their way in life using only their charms and good looks, rather than any more solid talents, are tragically undermined not only by Willy’s failure, but this viewpoint as well.

Nostalgia

The dominant emotion throughout this play is nostalgia, which is understandable given that all of the Lomans feel that they have made mistakes or wrong choices. The technical aspects of the play feed this emotion by making seamless transitions back and forth from happier, earlier times. Youth is more suited to the American Dream, and Willy’s business ideas do not seem as sad or as bankrupt when he has an entire lifetime ahead of him to prove their merit. Biff looks back nostalgically to the time he was a high school athletic hero and, more importantly, to a time when he did not know that his father was a fake and a cheat, and still idolised him.

Opportunity

Tied up intimately with the idea of the American Dream is the concept of opportunity. America claims to be the land of opportunity, of social mobility. Even the poorest man should be able to move upward in life through his own hard work. Miller complicates this idea of opportunity by linking it to time, and illustrating that new opportunity does not occur over and over again. Bernard has made the most of his opportunities, by studying hard in school. He has risen through the ranks of his profession and is now preparing to argue a case in front of the Supreme Court. Biff, on the other hand, while technically given the same opportunities as Bernard, ruined his prospects by a decision he made at eighteen. There seems to be no going back for Biff, after he made the fatal decision not to finish high school.

Growth

In a play, which rocks back and forth through different time periods, one would normally expect to witness some growth in the characters involved. This is not the case in Death of a Salesman, where the various members of the Loman family are stuck in the same character flaws and in the same personal ruts throughout time. For his part, Willy does not recognise that his business principles do not work, and continues to emphasise the wrong qualities. Biff and Happy are not only stuck with their childhood names in their childhood bedrooms, but are also hobbled by their childhood problems: Biff’s bitterness toward his father and Happy’s dysfunctional relationship with women. In a poignant moment at the end of the play, Willy tries to plant some seeds when he realises that his family has not grown at all over time.

Family, betrayal and abandonment

Willy loves his family very much, but has become obsessed with raising the ‘perfect’ son, which highlights his inability to understand reality or to communicate and listen to his sons’ own dreams and desires. In Willy’s mind, Biff is the embodiment of promise, and he is

attempting to live his life through Biff. However, when Biff discovers his father’s affair, he is very quick to abandon his father’s ambitions for him. In Willy’s eyes this was abandonment, and we can chart Willy’s life throughout the play as being punctuated by rejection after rejection, each time leaving Willy in a greater state of distress. Willy develops a fear of abandonment, which makes him want his family to conform to the American Dream.

We can pinpoint Willy’s stages of abandonment throughout the play: Willy’s father left him and his brother Ben when they were very young, leaving them no financial or historical legacy on his departure. Ben left for Alaska, leaving Willy with a warped vision of the American Dream. Willy was fired from his job, leaving him feeling unproductive, old and worthless. Likely a result of these early experiences, Biff's ongoing inability to succeed in business furthers his estrangement from Willy. When, at Frank’s Chop House, Willy finally believes that Biff is on the cusp of greatness, Biff shatters Willy’s illusions and, along with Happy, abandons the deluded, babbling Willy in the washroom.

Willy’s primary obsession throughout the play is what he considers to be Biff’s betrayal of his ambitions for him. Willy believes that he has every right to expect Biff to fulfil the promise inherent in him. When Biff walks out on Willy’s ambitions for him, Willy takes this rejection as a personal affront (he associates it with ‘insult’ and ‘spite’). Willy, after all, is a salesman, and Biff’s ego-crushing rebuff ultimately reflects Willy’s inability to sell him on the American Dream – the product in which Willy believes most faithfully. Willy assumes that Biff’s betrayal stems from his discovery of the affair with The Woman – a betrayal of Linda’s love. Whereas Willy feels that Biff has betrayed him, Biff feels that Willy, a ‘phony little fake’, has betrayed him with his unending stream of ego-stroking lies.

Is the play still relevant today?

Death of a Salesman continues to be performed in theatres around the world. We can understand why theatre-goers are moved by the play in the same way that 1949 audiences were. For example, we can see how ecologically Willy’s ravings about overpopulation, builders chopping down trees in favour of office buildings and blocks of flats still resonate with 21st-century audiences. Economically, Willy struggles to pay the mortgage and the bills that pass through the door far too frequently, and this too resonates with today’s audiences who feel financial pressure. Audiences still respond to the play’s exploration of the family unit and the relationship between family members.

Define: Symbols

Symbols are objects, characters, figures, or colours used to represent abstract ideas or concepts.

Seeds

For Willy, seeds represent the opportunity to prove the worth of his labour, both as a salesman and father. His desperate, nocturnal attempt to grow vegetables signifies his shame about barely being able to put food on the table and having nothing to leave his

children when he passes. Willy feels that he has worked hard, but fears that he will not be able to help his offspring any more than his own abandoning father helped him. The seeds also symbolise Willy’s sense of failure with Biff. Despite the American Dream’s formula for success, which Willy considers infallible, his efforts to cultivate and nurture Biff went awry. Realising that his all-American football star has turned into a lazy good-for-nothing, Willy takes Biff’s failure and lack of ambition as a reflection of his abilities as a father.

(Source: https://goo.gl/0ZZYz7)

Diamonds

To Willy, diamonds represent tangible wealth and validation of one’s labour (and life) and the ability to pass material goods on to one’s offspring, two things that Willy desperately craves. Correlatively, diamonds, the discovery of which made Ben a fortune, symbolise Willy’s failure as a salesman. Despite Willy’s belief in the American Dream, a belief unwavering to the extent that he passed up the opportunity to go with Ben to Alaska, the Dream’s promise of financial security has eluded Willy. At the end of the play, Ben encourages Willy to enter the ‘jungle’ finally and retrieve this elusive diamond – that is, to kill himself for insurance money to make his life meaningful.

Linda’s and The Woman’s stockings

Willy’s strange obsession with the condition of Linda’s stockings foreshadows his flashback later on to Biff’s discovery of him and The Woman in their Boston hotel room. The teenage Biff accuses Willy of giving away Linda’s stockings to The Woman. Stockings assume a metaphorical weight as the symbol of betrayal and sexual infidelity. New stockings are important for both Willy’s pride in being financially successful and able to provide for his

family, and for his ability to ease his guilt about (and suppress the memory of) his betrayal of Linda and Biff. Stockings, at the time, were highly sought after but very expensive and hard to get. Willy’s gift to his lover implies a complete disregard for his wife.

The rubber hose

The rubber hose is a stage prop that reminds the audience of Willy’s desperate attempts at suicide. He has apparently attempted to kill himself by inhaling gas, which is, ironically, the very substance essential to one of the most basic elements with which he must equip his home for his family’s health and comfort – heat. Literal death by inhaling gas parallels the metaphorical death that Willy feels in his struggle to afford such a basic necessity.

The tape recorder

This appears to signify change, a change in Willy’s life through the advancement of modern technology. This marks the end of Willy’s career. When Howard fires Willy from his job, there is a tape recorder in the room, which Howard is more interested in playing with than listening and talking to Willy.

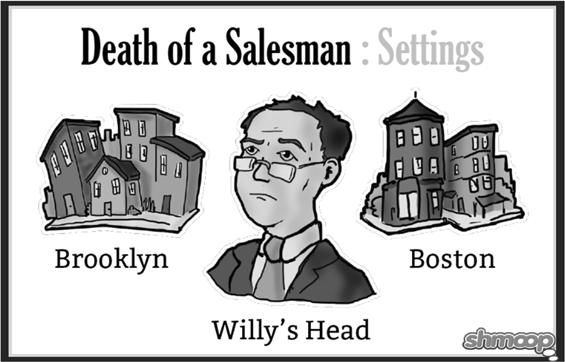

Setting

The play is set in America, more specifically, New York and Boston during the late 1940s. Most of the play is set in Willy Loman’s house and yard in Brooklyn, New York. The Lomans’ house is boxed in due to the recent population growth and housing developments. Throughout the play, the big buildings around their house are shown to suffocate the natural beauty that once surrounded the home. Before the buildings were there, there was enough sunlight to grow a garden and trees surrounded the home. The buildings have separated the characters from nature, which adds to their feelings of confinement and desire to escape.

It is also important to note that a good portion of the play is set inside Willy’s mind. The audience experiences many of the events through Willy’s subjective point of view, including flashbacks and blurred realities.

(Source: https://goo.gl/F0fjk1)

The time period also has a big effect on the action of the play. It is set in the late 1940s and America has just emerged from World War II. The country is set on rebuilding itself and everyone is determined to achieve the American Dream. The nation is also about to experience the massive economic boom of the 1950s, which means American commercialism is about to take off in a big way. This ties into many of the play’s themes.

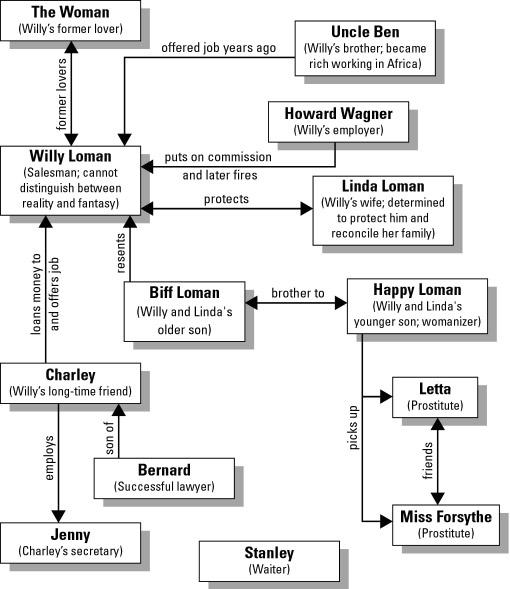

Dramatic structure

Dramatic structure is the sequence of a play or film. The dramatic structure of Death of a Salesman follows a classic literary pattern known as Freytag’s Pyramid – a diagram of a common pattern of dramatic sequence. Though the plot jumps from past to present, the dramatic structure follows a predictable pattern. As seen in the diagram below, Freytag’s Pyramid consists of the exposition (beginning), rising action, climax, falling action and denouement (ending). This play is made up of two acts and a requiem. A requiem is an act or token of remembrance. It is also defined as a speech or music celebrated for the dead. The requiem is the last act of this play, where the sad truth of Willy’s existence is revealed to the audience and the Loman family.

(Source: https://goo.gl/4zv0qp)

Staging and set design

Miller wanted the staging to be a combination of naturalistic period furniture and props alongside unnatural dream sequences. He wanted to build an atmosphere that was similar to ‘a dream rising out of reality.’ Stage directions call for a complete house for the Lomans. An audience will not only watch the action take place in the kitchen but can observe several rooms within the home. This seems as if it could be very distracting because it allows the audience to look at multiple sets while the action is only taking place in one area/room of the set. Miller solves this problem through lighting – only characters that are involved in the action are lit on stage and all other rooms, props and characters remain in the dark.

Below are a few examples of various ways in which the set has been designed for Death of a Salesman. In all these examples, the kitchen and the two bedrooms are visible, with the kitchen taking centre stage.

(Source: https://goo.gl/VQMsvw)

(Source: https://goo.gl/q0mqPU)

(Source: https://goo.gl/M3Al8b)

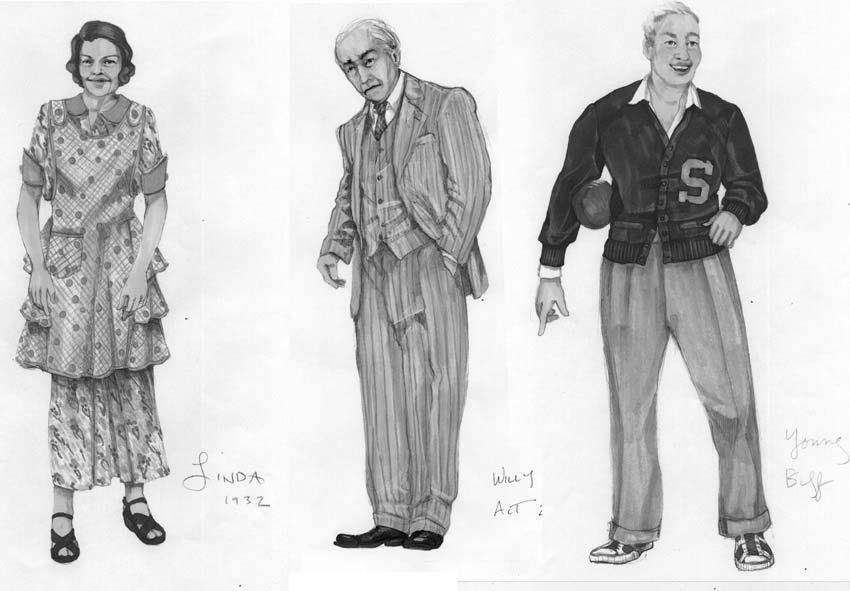

Costume design

The costume design for any production of Death of a Salesman is based on what people wore in the late 1940s. Willy wears a three-piece suit and tie (usually in grey, tan or brown), Linda wears a basic house dress and apron, and the boys also wear suits as well as their sleepwear. Costumes change here and there for the flashback scenes. Below are a few examples of costume sketches for various productions of the play.

From left to right: Linda in her house clothes, Willy in his suit and young Biff in his casual wear with his football jacket. (Source: https://goo.gl/SNW405)

Biff in Act 2 with a grey suit. Happy in Act 2 in a brown suit. (Source: https://goo.gl/ZtKi36) (Source: https://goo.gl/GPF5CO)

Staging the play and audience reception

The play has been revived on Broadway four times, with the latest revival being the 2012 production starring Philip Seymour Hoffman as Willy and Andrew Garfield as Biff. The production of this version was praised by The New Yorker with Giles Harvey calling some of the performances ‘magnificent’11. What the writer had a problem with was the play itself and how Miller’s writing left very little of the character development to the imagination and how much ‘glaringly conventional stagecraft’ the play was able to pack into its two acts. The New York Times wrote in the opening lines of its review: ‘I wondered why the play was revived at all.’12 With reviews like these, it seems as though the play might not have aged as well as one would have hoped. However, audiences will still find relevance to their own circumstances and this play is a classic example of excellent American theatre.