13 minute read

system

NAFDA NAFDA 10 WINTER/SPRING 2022

The innovative coalition ‘deep-cleaning’ Lebanon’s education system.

“Nafda - It means, ‘spring cleaning!’” Maria Hibri ‘82 says, animated, as she begins talking about the new education initiative that is empowering school communities to implement innovative, participatory approaches to education in Lebanon.

Maria Hibri

I initially met Ms. Hibri to discuss her own life and career. As the co-founder and designer of Bokja, an artisanal textile and design studio who’s fresh and bright take on traditional methods of embroidery has garnered worldwide fame, she is a grande dame of the Lebanese design scene.

Though Hibri kindly spoke about Bokja’s founding and its many accomplishments in the 20 years since, it soon became clear that this was not really the story she wanted to tell.

“What I really want to talk about is Nafda. Bokja, you can Google it. The story is there,” she states bluntly. This is true - there are plenty of articles detailing the studio’s story and successes over two decades.

“I feel I owe it to myself to be involved in things that really matter to me.” Hibri reflects.

To be clear, Ms. Hibri has not been on the sidelines for the past 20 years. She has long been involved in community organizing and is an outspoken advocate for a number of social and political causes. Most of Bokja’s collections are, for her, a vehicle to “speak her truth.” Carefully woven into the aesthetically stunning textiles, pillows, and robes, Hibri states, are “our aspirations, our anger, our questioning of things.”

The design duo has created pieces that take a stand on the extinction of bees. They wrapped tires in fabric to protest political frustration in lieu of the usual burning of tires which causes pollution. During the 2011 Arab Uprisings, they worked with Bokja’s artisans, who are from all over the Arab world, to create two tapestries, upon which each craftsman expressed their story and views. The tapestries are now on permanent display at The Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris. Post-port explosion, they turned their studio into an ER for damaged furniture, mending upholstery tears with a red thread, tending to the city’s wounds.

Nafda, however, is cut from a different cloth. It began from the many virtual Thawra WhatsApp groups that Hibri was a part of during lockdown. She was exhausted and frustrated that the uprising’s momentum was dwindling. “It seemed this was as far as we could go as Lebanese, that there was no united voice, or bigger picture” she recalls.

Enter Nadim Matta ‘76, a veteran of the development world who possessed both the will and the way to tackle some of the country’s toughest problems. Maria (re)connected with her fellow IC graduate on one of these many Zoom calls - one of the few other people she met who was thinking critically about how to take action.

Matta has been based in the US for a number of years, where his organization, the Rapid Results Institute (RRI) is headquartered. Building on his years of experience with Save the Children, USAID in Lebanon, and in private sector social impact consulting, RRI is a different way to think about development.

Its bottom-up approach is centered around the idea that peoples’ problem-solving capacity can be unleashed when they are given the tools, resources, and confidence to set and pursue very ambitious, shortterm goals in creative and innovative ways.

Maria also brought an old friend, Fawzi Kariyakos, into their conversations. He, too, was frustrated with the lack of tangible change he had witnessed and was looking for a more radical approach to address the crisis. Together, the three decided it was time to act.

Through all of their brainstorming, the trio kept returning to the same questions, Hibri recalls. “Why is it that the concept of citizenship in Lebanon is so diverse from one person to another? How can we make our diversity what is rich about us, instead of our weakness?”

In retrospect, schools are the perfect place to start. What better way to effect bottom-up, sustainable, transformation and instill common values of citizenship, communitymindedness, leadership, and social justice, than to encourage these ideals in the malleable minds of young children?

They began at the top level, focused on governmental reform, but they quickly realized systemic overhaul might be more digestible in bite-sized pieces.

A general idea arose. If citizens take over a sector, and design and build alternative modes of governance through a participatory approach anchored in values of good governance, shared citizenship, and social justice, then they can address some of their most pressing challenges without the need for traditional government intervention and thus build a self-sustaining system.

It was not until they connected with current Nafda team member, Fahd Jamaleddine, that the education sector came into view. Fahd was already familiar with the sector through his own work on sustainable education reform, and he organized an introductory call with the emerging Nafda team and six principals from public, private, and semi-private schools across Lebanon.

“To me,” Nadim recalls, “the real ‘aha’ moment came on that Zoom call. I realized that there is a possibility here, because there are people on the ground who haven’t given up, who are not only being resourceful and creative in how they are trying to salvage this sector, but are also doing really cool and innovative things

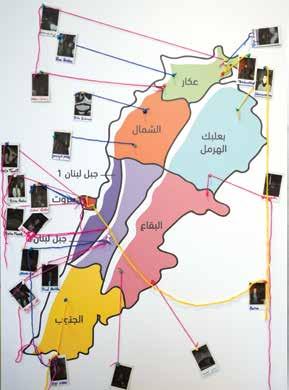

Nafda’s network

They decided right then and there to build their movement around these agents of change. The bet was that these six principals were not just a one in a million example, but were part of a larger collective of educators and administrators who were interested, committed, and believed in the idea, and necessity, of creating a better education system.

Thus, Nafda was born. The ‘Jedis,’ as Maria jokingly refers to her fellow advisory board members, mostly of her generation, recruited a team of passionate, and highly qualified individuals who have extensive experience in education and development to help actualize and lead the project.

Ghia Osseiran ’00 is one of these bright, young, experts. A graduate of AUB and Columbia, Ghia worked for the UNDP and ILO before pursuing her PhD in Education at Oxford University. Though her research is focused on graduate labor market outcomes, her extensive knowledge of the economics of education and experience in development at both the international and grassroots level, means she is keenly aware of the importance of education and participatory approaches to sectoral reform.

“At first I thought the project was overambitious,” Ghia admits. “But, also, really exciting. I really liked that it was a citizen-led initiative. I could not not be involved, because it’s such an important sector and I want to help in any way I can.”

Despite being a country that strongly values high quality education, World Bank statistics reveal that Lebanon’s education systems are performing very poorly compared to global standards. It’s estimated that for every 10 years a student attends school, they will only reach the learning outcomes of 6.2 years

of school – four fewer years of actual learning on average. That’s a number from before COVID and the economic crisis, meaning there is at least an additional 1-3 years of learning lost, Ghia estimates.

“The education sector cannot be left behind.” Ghia adamantly states. “It’s your human capital, your future. The ramifications if it is forgotten are huge. And it’s already happening.”

Furthermore, education is the place to start because change stems from within the classroom. “Democracy starts within the classroom. Empowerment starts within the classroom. Modeling good citizenship starts within the classroom,” Ghia says. “Ways of teaching and learning and the culture of the school, in terms of how inclusive decision making is, can have a huge impact.”

To support the sector’s immediate needs and promote systemic change, Nafda provides technical and financial support to schools. Nafda has selected a first ‘cohort’ of 20, distributing up to 30% of funds to address immediate needs, before embarking on long term reform initiatives.

On the first Zoom “information session,” 200 schools from across Lebanon were present. Ultimately 33 schools submitted applications, which the team meticulously reviewed, including site visits to each of the candidates, before selecting the official 20 participants.

These site visits and related conversations with school leaders were particularly insightful, humbling, and inspiring.

“It was personally very eye-opening,” Ghia reflects. “There were certain public schools that really surprised me in terms of how participatory and innovative they were despite limited budgets. It totally changed my perceptions about the public school system.” of the crisis, but public schools in particular are buckling under the weight of fuel prices, transportation challenges, and supporting teachers. They have had to be incredibly resourceful, especially without government support.

Ghia recalls one principal in Mount Lebanon who raised funds within her community to make sure all her teachers were paid their salaries in full last year. Though the government covers permanent teachers’ salaries, most teachers are on fixed-term contracts and have not been paid at all. This principal made sure they were.

Maria was similarly in awe of the schools she visited and educators she met. She went to a public school on the border of Syria where she met an incredible principal who was changing her entire community through her work on early marriages. “Many girls there marry around 14 and 15, so she was making funny videos and skits about early marriage and the importance of prioritizing education. She also made a huge effort to re-enroll girls after they had gotten married, to continue their education.”

The innovation, effort, and dedication from school actors all across the country is there. What would the education system look like, then, if all of these schools started working together? This is what Nafda aims to tap into.

Ghia Osseiran

Since selecting the first cohort in January, they have surged full steam ahead. During the first weekend of February, they held a two-day conference,where schools got to know each other, and the program’s ground rules were established.

They also began preparing for the ‘Community Visioning Process,’ where members of the wider school community - from teachers, parents, students, administrators and townspeople - come together to establish what the school’s priorities and goals are, which will ultimately inform the School Transformation Projects.

These projects can be anything, as long as they have been determined by this participatory process. The Nafda team, however, strongly encourages schools to think about how to incorporate the core principles of good governance, citizenship, and social justice into their projects.

Once the schools decide on the transformation projects, Nafda divides participating schools into “labs,” where they will work together based on stated project plans. Let’s say, for example, that three schools want to work on increasing inclusion. These three schools will be placed into one “lab,” where they will be connected with solution providers, or NGOs who have already developed a framework for inclusivity.

This is Ghia’s main responsibility - building a coalition of NGOs and service providers. The idea is to tap into Lebanon’s rich civil society and existing efforts. There is no need to start from scratch when you can connect existing programs. Ghia is researching what programs and initiatives are already out there, connecting with the NGOs, and bringing them into Nafda’s sphere. At the time of writing, they had partnered with over 20 organizations.

The “labs,” with the support of the Nafda team and related NGOs, will then work together to determine what goals they want to set and how

they want to approach the final step - the 100 days project.

The point of the 100 day project is to set overly ambitious goals to see what institutions can accomplish within a limited time frame. Stimulating this “shock” to the system gets people to think through very different, creative ways of approaching issues and organizing themselves, in terms of more equitable leadership and selfgovernance. It is a strategy employed by Mr. Matta’s RRI, which has garnered huge success globally.

This first cohort will likely be working on their project through June. The hope is that, not only will these pioneering schools achieve their goals, but that their projects will stimulate similar transformation projects in other schools around the country. The ultimate goal is to reach 1,000 schools in 3 years.

“It’s overambitious, but that’s the point,” Ghia asserts. “We need to try things differently. If we are able to successfully use the participatory approach and it spreads to other schools and sectors, I think that’s really groundbreaking and a different way of doing this in this country. That has a lot of power.

In the meantime, 50% of the grant funds for immediate needs have been dispersed. But it’s not the money, necessarily, that has really excited the first cohort. Rather, it’s the human capital. For many school actors, this is the first time they are connecting with other directors from very different areas and backgrounds over shared experiences, struggles, and most importantly, solutions. As Ghia affirms, “Change is not going to happen unless it’s like this - when you have all these different schools coming together. Collaboration and exchange is very enriching.”

Directors are very eager to support each other. During their meetings, if one school mentions they have a problem with something, another director will likely jump in and say, “Give me a call after. I have figured this out.”

The Nafda team has realized they don’t have to sell the notion of good governance and social justice. “Directors keep coming back to it in our discussions. I think it’s because it was on their minds. It’s not like we came in with something new. We just gave them a platform,” Nadim relays. Success is far from guaranteed. As all three admit, it’s a hugely ambitious project. But they strongly believe in it, and understand the potential for return is huge. To Nadim, “success is that our organization is no longer needed in 3 years.” It means a selfsustaining movement, with directors and educators pushing themselves, and each other, towards principles of good governance, engaged citizenship, and social justice, and better integrating the school and community writ large.

Back in Maria’s studio, discussing Nafda’s potential brings a smile to her face. Despite her measured outlook, her self-proclaimed “endless well of optimism” can’t help but shine

It is important to emphasize that this project is not just focused on underfunded schools. In fact, it’s essential that elite institutions participate as well. At present, even if a school is already teaching principles of citizenship and social justice, only those graduates will benefit. As Maria states, “It’s like putting salt in the sea.” IC is participating in this first cohort, which the team is very excited about. IC does have the knowledge and resources to help build up other communities around them. To this end, IC has been in conversation with the Nafda team to discuss how best to through. “I believe in the magic of Lebanon, in its human capital, and in this group of people,” she asserts.

What makes Bokja so attractive is how unique, bold, and fresh its textiles are - a mix of the repurposed old and the new, to construct something rooted in tradition yet also entirely modern. Unique, bold, and fresh are perhaps exactly what Lebanon needs. And with a team of passionate experts scavenging and stitching the scattered pieces of Lebanon’s education sector together, this new tapestry is starting to tell a very exciting story.