5 minute read

WORLD: MYANMAR AND ME

Student Experience: “Hear me when I am asking for help because I’m breaking the law by speaking out”

Growing up, Lilly Oo never felt safe in her own country. Although she grew up in Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon, and was able to attend an international school, her mother repeatedly warned her to keep her head low, avoid confrontation with military personnel and stay away from conflict.

Advertisement

“When I was young, my mother always told me, ‘Don’t get on the bad side of the military guys, even when they’re wrong, you need to talk to them nicely,’” said Lilly during a Microsoft Teams meeting on 10th February.

Following the coup on 1st February, protests continue to rage across Myanmar’s most notable cities, and Burmese nationals have taken to social media to speak up against the actions of the military. Images of the violence that has spread in Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw, and elsewhere are gaining an audience alongside the hashtag #WhatsHappeninginMyanmar and #HearTheVoiceofMyanmar.

“Gen Z especially have been coming up with creative ways to protest. We know that we don’t have any weapons. They are the ones who can harm us, so we have been coming up with creative ways to push civil resistance,” said Lilly.

Myanmar has a tumultuous history, and this is not the first notable protest that has occurred against the military junta. In fact, nearly every decade during the 50 years of military rule between 1962 and 2010 saw its share of antiregime protests in urban areas across the country, some of the most notable being the 1988 Uprising, and the Saffron Revolution in 2007.

The world watches as Myanmar protestors fight back against ongoing disruption to their democracy.

Lilly’s mother participated in some of these protests, calling for an end to the military regime and a pro-democracy state. “During the 1988 Uprising, my mom saw people killed in front of her eyes; some of her friends died,” said Lilly. She continued: “In 2007, during the Saffron Revolution, I saw tanks coming in and saw monks taken away. That’s why we were all panicking when we saw the tank on 3rd February in Yangon. It felt like history was repeating itself. I don’t want to see my loved ones die.”

Lilly is an international student studying fashion art direction at Manchester Metropolitan University. She has been keeping in touch with her family and friends as best she can, but the military, after initial widespread internet disruption, has continued to limit internet services in several places across the country and block popular social media sites.

“I’m really worried right now. The internet is unstable, and people don’t feel safe. We don’t know when we will lose contact entirely,” said Lilly. Many protesters are still using VPN services to continue to speak out on social media, but there are concerns that these too will be targeted and blocked.

The military seized control with claims of voter fraud following the November 2020 elections, which saw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party win by a landslide general vote. According to the Myanmar election commission, this claim is not substantiated. Ms Suu Kyi has been placed under house arrest, along with a number of NLD officials. Power has

#HearTheVoiceofMyanmar

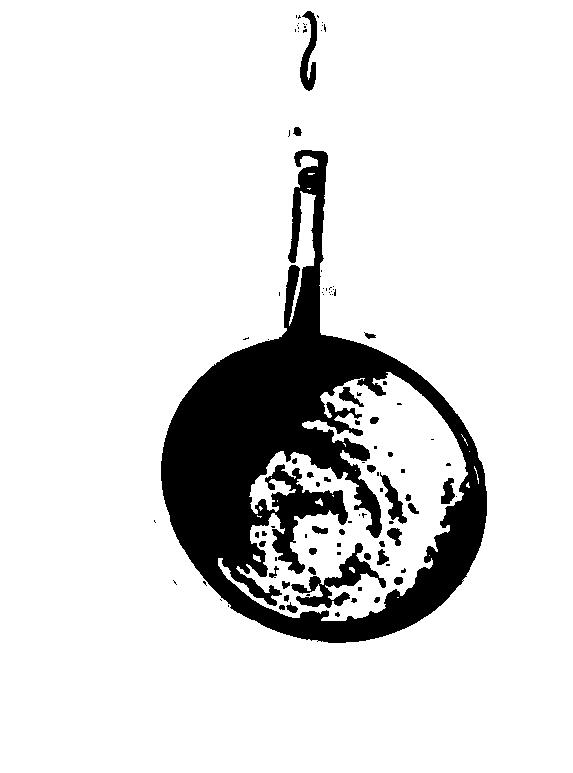

been handed over to military commander-in-chief, Min Aung Hlaing. Large scale protests, which began 6th February, called for the release of Ms Suu Kyi and other officials. Initially, these protests remained peaceful. Burmese citizens took to holding three fingers in the air as a symbol of resistance against authoritarianism. Demonstrators have also begun banging pots and pans every evening at 8pm. “It goes back to our culture. We evict evil spirits by banging pots and pans. It fits the context because we see [the military] as evil,” Lilly explained.

Protests took a violent turn three days later when police attempted to disperse the crowds with water cannons, rubber bullets, and tear gas, and in the instance of 19-year-old Mya Thwe Thwe Khaing, live ammunition. According to Reuters reports, a bullet penetrated Ms Khaing’s motorcycle helmet, and doctors stated that the wound looked consistent with live ammunition.

Ms Khaing died from her injury at Nay Pyi Taw Hospital ten days later on February 19th.

“I think it’s going to continue to escalate. Right now, the military hasn’t backed down at all, and it’s gotten worse and worse. They haven’t taken a step back and we’re trying to spread awareness through social media, but the military has shut down media and television channels. They are only allowing the military broadcast to be seen by people. It’s scary,” said Lilly.

Ola Almgren, the UN Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator in Myanmar, said: “The use of disproportionate force against demonstrators is unacceptable,” in an official statement released on 9th February, the same day Khiang was taken to hospital for her injuries. US President Joe Biden has issued an executive order to impose sanctions on leaders of the Myanmar coup. In a statement released on 12th February, he said: “The people of Burma are making their voices heard and the world is watching.”

#WhatsHappeninginMyanmar

Lilly says the most important thing people can do right now is spread awareness. She said: “There are many countries around the world who are still suffering like we are. Human rights are being threatened every day. We want the international community to help us. We want them to know that things like this exist all over the world.

“Raise social awareness. Don’t let the news die down. They must know that even if we are shut off from the rest of the world, it doesn’t mean the problem has stopped. It’s ongoing. I want people to keep that in mind.”