9 minute read

Forty Minutes

by Bradley Paul Edin

Tom Sherwin resists the temptation that after twenty years still beguiles him, to press the button which would allow him another nine minutes of sleep. Instead he stops the alarm. He turns back the bedcovers gently and as gently removes himself from bed. He means to be considerate both of his sleeping wife and of his unpredictable back. Diane does not awaken. She would appreciate his care, but twenty years have trained her to sleep through his nocturnal ramblings, and she is oblivious to it. Tom fumbles more than usual as he pulls on his jeans and buttons them. He and the ewes are midway into the second week of lambing, and his broken nights are beginning to tell on him. He thinks for the hundredth time that his fumbling is the foolish price he pays for still wearing Levis with a button fly. As he pulls on a sweatshirt, conveniently button free, he acknowledges that in the daylight he will again judge the price commensurate with the pleasure. His jeans still make him feel young, and dealing with the fly still imparts a fragrance of desire and potential consummation. The perfume is weak now, but it lingers. He goes to the back hall, where the chore clothes hang. Tom puts on his scarf, coveralls, boots, cap, and gloves, and goes into the night. The dog joins him. He trusts the dog will detect a mountain lion before he does and warn him somehow. Everyone knows that by the time you realize a lion is stalking you, it is too late to do anything. This seems a useful bit of information to take to heart, although he wonders how one could possibly verify it.

Advertisement

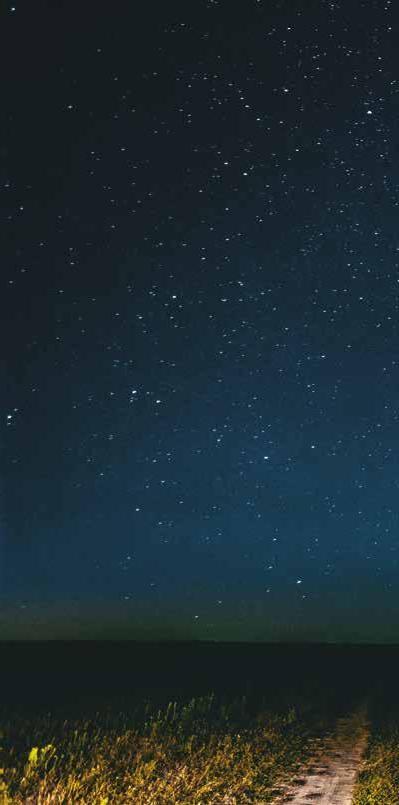

The moon is just past full, and the encrusted snow, flecked with black, returns its already reflected light. The night glows. It would be a good night to ski. He and Diane used to ski on moonlit nights, before the children came. Each became a devotee of cross-country skiing in college, and mastered the then necessary techniques of pine-tarring and waxing and scraping, applying klister when appropriate or—as Diane did—refusing to use the sticky uncooperative compound regardless of the temperature. Waxless skis, pragmatic but somehow heartless, replaced their old Bonnas when the children were old enough to join them on the trails Tom would cut in their woods, and now the old skis, their lignin edges chipped through long use, are carefully stored in the attic of the shop. Diane has suggested using them decoratively, over the fireplace or on the front porch. He puts her off, and secretly yearns for the smell of a propane torch and bubbling pine tar.

Tom thinks of Easter. “First Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox”: this is a fact his fourth-grade teacher once communicated to him and his classmates. He supposes this datum is no longer imparted by the Miss Nogoseks of the world, that it has gone the way of penmanship—and Swix colors. The equinox has not come yet; the world will have to wait for another full moon to experience again the thrill of resurrection.

Tom excludes the dog when he lets himself into the barn. He tells her to look for mountain lions, knowing she will instead find deer to bark at in the hay yard. He is wide awake now; the lambing barn is just far enough from the house to make a man wide awake. It occurs to him that he should thank God to be wide awake so often. So many of his neighbors are always slumbering.

---

Tom Sherwin never expected to be a farmer. He was never sure what he had expected. He had grown up solidly middle class and thoughtlessly urban. He had many aptitudes, but few passions, and neither medicine nor law nor ministry nor business nor academia nor engineering attracted him. In his family these were the legitimate aspirations, but they were not his. Indeed, he had never even expected to marry. Only one thing was he passionate about: simple living.

College in the seventies had been full of simple living for those who had ears to hear and eyes to see. In the cafeteria with fellow heretics (he was majoring in economics, which, by the time he graduated, he decided truly was a dismal science) he excoriated the priests of Keynesian orthodoxy who were their professors, and extolled Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful and Heilbroner’s Inquiry into the Human Prospect. These men gave language to what Tom thought he had always known and feared and been set apart by. Like Tom, they did not believe the only limit in life is death.

Halfway through his college years, Tom’s father’s business suffered several reversals. Lloyd Sherwin survived his financial troubles, as people generally do; in his case he and his self-respect were saved by the timely death of a maiden aunt. But the eighteen months of broken but, to the son, strangely not disillusioned spirit led Tom’s father to admit to himself that he hated what he did for a living. He began to retire some years before his retirement became official. Tom, who judged his father a victim, was the real sufferer. The events, private and public, of those years undermined Tom’s hopes for justice, fair play, loyalty. Playing by the rules, as he supposed his father had done (many years later he would realize his father’s situation, like everything else, was not so simple), ran headlong into the limits he saw everywhere. Tom got his B.A., but the only thing he really carried with him from his undergraduate days was his devotion to simple living. He fell into newspaper work, which still remained a vocational option for the unambitious.

Diane and he met in church. They were both attending the annual conference of the Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa, and had separately escaped the endless numbing talk of genetic conservation and the evils of factory agriculture by finding an early church service. The congregation was one of those that leave visitors who choose to stay for coffee to their own devices, and Tom and Diane found themselves thrown together by default after worship. They were both thirty-five years old. In spite of Tom’s lack of ambition, his reportage was in demand and he contributed often to various progressive magazines. Diane wanted children. One year after they met they moved to her home place in southwestern Minnesota, and married a couple of years later.

Throughout their twenty years together they had been devoted to each other, and for at least a few years believed they were in love. Maybe they still were, though when Tom thought about it he knew he could not say. He remained unambitious, a man of inertia or, as a eulogist might say, content. About one thing did he remain passionate, simple living, though of course the simple living had become complicated living in their efforts to keep it simple. The free-ranging chickens, the produce in the root cellar, the homemade bread from home-milled flour, the mason jars filled with summer’s bounty all only happened because of careful time management and endless work. Tom appreciated this, and appreciated his wife’s willingness not simply to humor his passion, but to help him indulge it.

But Diane did not share Tom’s enthusiasm. The only thing she was passionate about was the farm, this farm where she had grown up and was now raising her family. Long before he proposed to Diane, Tom knew she was more devoted to the farm than to him. Her parents were good about them, and pretended to accept their not being married, though when their daughter and her partner regularized their relationship in the sanctuary of Ringsaker Lutheran Church, Paul and Caroline’s relief was plain. Tom’s father-in-law had been a good mentor, teaching him about pigs and sheep and gracious about allowing experiments and tolerating mistakes begotten of inexperience. The older man was taken aback at first by Tom’s fascination with the old ways, his not being in love with Big Iron, his interest in organic farming and direct marketing and biodynamics. But their partnership worked. The place had always been a stock farm, Tom took to husbandry, and Diane loved promoting and selling their lambs and hogs to people in the Cities who could afford to pay premium prices for their food. All went well, and when the children came, what could go wrong? Little had.

Diane’s parents were dead now, resting in the Ringsaker cemetery. The last of their children would, within a few years, be gone. Tom doubted any would come back; simple living had required so much effort.

---

Tom turns the barn lights on. All but two ewes are resting in the straw, sleeping, dozing, chewing their cuds. Some lambs sleep on their mamas’ backs. The oldest lambs are already acting like adolescents, hanging out together, keeping one another warm, only seeking their mothers when they are hungry. Tom is filled with joy as he looks at his eighty ewes and considers that the only people who see such sights are those who get up at three in the morning. He checks the two ewes that are standing. One, who has lambed, is cleaning her baby off and murmuring, occasionally pawing it with a foreleg to assure herself it is alive. The other ewe is having trouble; Tom sees one leg projecting from the birth canal and sees exhaustion in the ewe’s eyes. He debates washing up, but decides he is clean enough and that neither the ewe nor her lamb can wait. He pushes up the right sleeve of his coverall and reaches his left arm around the ewe’s neck. She does not protest; she has done all she can and failed, and she collapses. Tom pushes the exposed leg back into the ewe, with his right hand embraces a head, finds a second leg bent backward, pushes the head back, pulls both legs forward, eases the head through, and pulls the lamb out. He wipes its mouth and nose clean and places it in front of its mother. He reaches in again; there is a second lamb. Soon it is out too. The activity has revived the tired ewe, and she is on her feet, licking, murmuring, pawing. A few minutes more, and ewes and lambs are penned in their jugs. The lambs’ navels have been iodined and colostrum is in their bellies. Tom has given little thought to any of it, except the general wonder of new life, which for him remains remarkable.

At the barn door his dog waits, and together they walk to the house. When, Tom wonders, did it become so easy? Not routine; routine it has never become. But easy, certainly.

He washes his hands and arms, and puts on his pajamas. Forty minutes have passed since he went out to check sheep. He sets the alarm for six a.m. and gets back into bed.

BRADLEY PAUL EDIN is a Lutheran pastor who has served parishes in North Dakota for the past thirty-five years. A native of Jamestown, he lives on the family farm south of Valley City. Currently he is pastor of four congregations in southeastern Barnes County.