9 minute read

Putting Diversity into Practice

An Interview with Cardinal IG Plant Manager Mike Arnston

By Meg Luther Lindholm

Advertisement

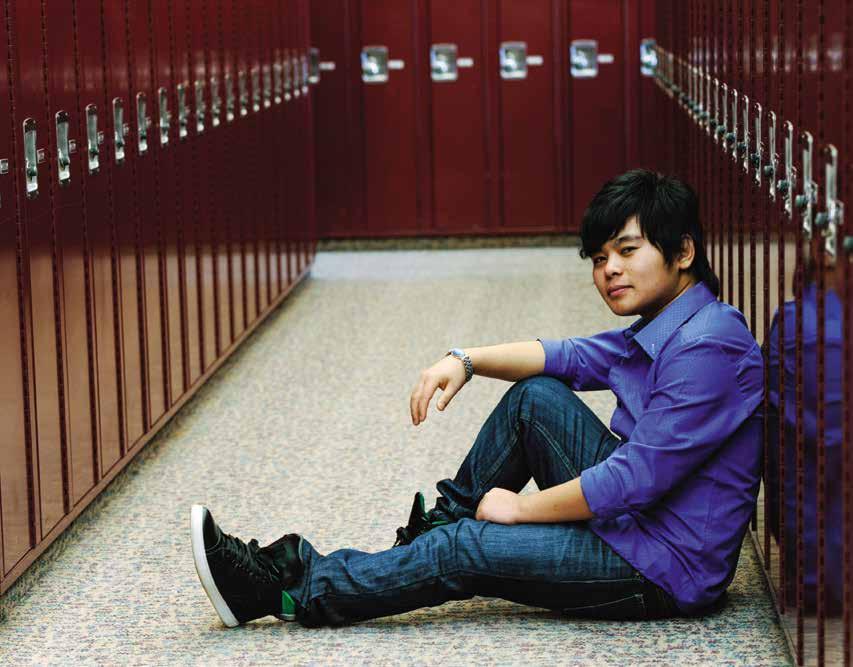

If you want to find cultural diversity in North Dakota, look no further than Cardinal IG (Insulated Glass) in Fargo. The factory, on the western edge of town, manufactures insulated glass for window companies like Marvin Windows. When the factory was built in 1998, many immigrants and refugees found jobs there. Fluency in English has never been a requirement, and the company has a reputation for treating workers fairly. Today there are 285 employees from twenty-three countries working around the clock in eight-hour shifts. The countries include Bhutan, Bosnia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iraq, Liberia, Mexico, Nepal, Romania, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo, Vietnam, and the United States.

Mike Arnston has worked at the plant since the beginning and is now the factory’s top manager. He says it was never anyone’s intention to hire refugees—it just happened, and it worked. Meg Luther Lindholm first visited the plant in 2003 and 2004. She recently returned to photograph and interview current employees and to ask Arnston how he manages such a diverse workforce.

Meg: How did Cardinal IG come to be such a diverse workplace?

Mike: Well, we’ve always hired the best qualified candidates at Cardinal IG, and sometimes that means those people weren’t born in the United States or in some cases don’t even speak English, but they happen to be the best candidates for the job. There was no plan to develop a diverse workforce. It just happened.

It is interesting to see that so many refugees who were here years ago are still working here. Why do you think that is?

I think we have a good culture here, and when people begin working here, they keep working here.

What is the culture?

It is five values: family, safety, teamwork, excellence, and respect, and we live by those values. The employees who work here helped to choose those values. And anyone that seeks employment here is hired based on being able to operate within the realm of our corporate values.

Talk a little more about respect—how that is operationalized, and what that means.

Respect is one of our five values. Folks are raised in different cultures and different religions, and we all have to respect each other as human beings. If we can do that and make accommodations where necessary for religion or cultural differences, then we do that. If an employee comes to me and says, “Hey Mike, I have a church program to go to at the Lutheran church,” then we try to make accommodations. It’s no different if an employee says, “Tomorrow is a Muslim holiday. I need to go to the mosque.” We try to make accommodations for that sort of thing.

What happens when there are disagreements or arguments?

We talk about walking a mile in someone else’s shoes before they disagree with them, and we try our best to live by that rule of thumb. So when two employees aren’t getting along, it’s really no different than two employees that grew up in same neighborhood. When they don’t see eye to eye, it’s your job as a leader to facilitate understanding. I don’t know that we have any more challenges here at Cardinal because of diversity than any place else without diversity. There’s always going to be disagreements, and everyone just needs to respect each other and understand that sometimes we may not agree.

Talk about the company’s zero tolerance rule.

We cannot tolerate things like racism or any type of discrimination based on religion. But guess what? That’s the law. There’s no special sauce there. If other companies are doing things like that, they ought not to be. There’s no wiggle room. That’s not to say there haven’t been situations where people have been discriminated against, but we work through those—and depending on the severity, sometimes we’ve had to say if that’s your belief, then this is not the right place (for you) to work.

Other times we’ve had to teach people about what it means to live in the United States of America. Some cultures don’t value women, or they value women in a different way than we value women or respect women in the US. And even though you didn’t grow up with it in your culture, if you’re going to live and work in the United States, that’s something you have to get used to. We’ve had to educate some folks about what it means to have a supervisor who’s a woman.

What are the criteria for hiring here?

When you apply to work here, we have a couple of different screening tools that we use. There’s a computer test that tests primarily for math skills. If they pass that, then they take a values survey to survey what their personal values are. And we do an emotional intelligence survey. Then based on those tools, employees are ranked within our available-to-hire pool, and then supervisors are contacted to conduct interviews. Then based on those interviews, they’re hired by their production supervisor.

So as far as the actual mechanics of job—math skills are important?

Math skills are pretty important for most of the jobs we do here.

But English is not.

Not necessarily. If you’ll be on a team where the team leader speaks languages other than English, as long as you speak one of those languages, then you’ll assimilate to that team pretty well. If you work next to someone who speaks the same language as you, we can communicate through that other person.

Are you ever concerned about the backgrounds of people who are recent arrivals from other countries?

No. We have pretty thorough screening tools that are used by the immigration services and the (US) State Department, so we basically assume that if someone passes those screening tests, then they’re eligible to work here. We’re not going to come up with a screening method here at Cardinal IG that’s better than our intelligence services. There’s been concern about immigrants coming to work in the United States since the United States became the United States. People have been immigrating here for a few hundred years now, so that shouldn’t be unusual for the United States.

What shouldn’t be unusual?

That we’re going to be a country of immigrants. I mean neither of us are Native Americans, so at some point our relatives immigrated to the United States from somewhere else for opportunities they didn’t have wherever they came from—whether economic, or religious, or whatever. People come here to start a new life. I mean, I can understand where it’s a concern when we have terrorist attacks taking place around the world. But the United States will never shut its borders.

In addition to managing employees at Cardinal IG, Arnston has also had a career in the US Army. In 2005 he was sent to Sinjar in northwestern Iraq as a civil affairs team leader, where he stayed for a year. His job was to advise his unit’s military commander on ways to help civilians in areas with fighting between insurgents and the US/Iraqi military. His team dug water wells and repaired schools, among other projects. In a somewhat ironic twist, he found himself in the place of his Cardinal IG employees—an outsider trying to understand a new culture and language.

How did your experience at Cardinal IG influence your experience in Iraq?

I knew a little bit about the culture, because we had a number of Iraqi and Kurdish associates working here. So just through my job and getting to know them, I got to know something about their culture. I even knew a very little bit about the language, so I was able to say “hello” and “thank you,” which goes a long way, honestly, in a foreign land to show you are trying to connect with them. And knowing that our associates here had fled Iraq right after the First Gulf War, I felt I had some connection. I saw people there (in Iraq) in similar circumstances to the ones that had prompted our employees to leave.

So it gave you an understanding of the journey your employees had gone through.

Yes, except that I sort of saw it backwards.

And you were in a situation where now you were new to the place, new to the culture, new to the language.

Right, and I talk to people about that now—about how it stinks sometimes, for example, that we shut down on Christmas Day here. Well, it kind of stinks for some of our employees who have religious celebrations on days we don’t take off. We try to accommodate as best we can, but we can’t shut the plant down. But I talk about how in Iraq I worked on Christmas Day and I took the Eids off, because when in Rome, you gotta do as the Romans do.

What else did you learn in Iraq that influenced how you run the business now?

Maybe I have a better understanding of what a refugee from another country has gone through—some of the hardships— because I’ve seen it.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Having worked with a diverse workforce almost since the beginning, this is not amazing to me. This is normal. We have something special here—a special culture. But to me these are just Cardinal associates. They’re my Cardinal family. That many of us come from different backgrounds, it’s cool, but it’s not that big of a deal. And that’s the way it should be. The United States is a melting pot; it always has been a melting pot.

Since moving to Fargo in 2002, MEG LUTHER LINDHOLM has worked as a freelance radio producer for Prairie Public Broadcasting and National Public Radio. She also produces photo documentary projects using visuals, text, and sound to explore how social, cultural, and political issues impact individuals.