12 minute read

A Case of North Dakota Nature Preserves

By Jennifer Strange

It’s a right bison jam—massive brown beasts in every direction. The first ones are down in the waterhole to the left of the car. A small pool with frozen edges, it resembles a silvery-gray theater in the round, spindly black treetops forming a roof overhead. Three huge, brawny mounds shoulder each other. Their heads are bowed, muscular black tongues working the pond’s surface just now thawing after October’s early freeze. We drink in the moment.

Advertisement

My husband Terry and I have brought our visiting friend Liz on a day-trip to the Theodore Roosevelt National Park North Unit, a 24,000-acre reserve that stretches through the Little Missouri Badlands in the southwestern quadrant of North Dakota. Liz has traveled to the High Plains from her home in Washington, D.C., to see our new apartment and to witness for herself the booming Bakken oil field region. The two of us grew up six hundred miles southeast of here, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and have been best friends for exactly three decades. For the last two of those decades, we’ve lived a continent apart, she on the East Coast, I on the West. Terry and I shaved about 1,400 miles off of that distance last year when we relocated from southern Oregon to the cowboy town of Killdeer, North Dakota, a century-old outpost, population 800, that sits along Highway 22 in the foothills of the historically battle-worn Killdeer Mountains, right on the eastern border of the Bakken shale formation.

Because most Dakotans—especially those of us who have left the area— keep tabs on our similarly named sister state (as if somehow we’re all related), Liz and I had been closely monitoring North Dakota’s oil boom for years. At first we were shocked by how much media attention our neighbors were getting; after all, this was the vast and sparse Great Plains, the “Great Flyover,” the place we left because there was nothing going on. Gradually, though, our taunting gave way to genuine curiosity and we brought our husbands into the conversation: Could a person (perhaps Terry) earn back the retirement savings he’d lost in the Great Recession by working in the oil patch for five to ten years? Could he do it without risking health and safety? Could a freelance writer (perhaps me) survive and even thrive on the prairie?

In early 2013, Terry and I decided to take the chance. He landed a job with a fourth-generation, locally owned transportation company, bravely moved himself and a carload of stuff across the country and has been happily driving a water tanker ever since. Seven months passed before I got all the loose ends tied up in Oregon, secured us an apartment, and joined him in this grand adventure. These days, while my husband’s at work, I am tapping away at my latest project, accompanied by the strangely beautiful view from our third-floor windows: tornado-shorn treetops, a dulling metal grain elevator, and, in the distance, the long, low butte that frames each day’s flaming frontier sunrise.

Liz called soon after we’d settled in. She’d booked a flight. One Monday morning in mid-November, I drove the forty miles to Dickinson’s busting-at-the-seams Theodore Roosevelt Regional Airport to pick her up. We immediately set about touring the area’s newly human-crafted horizon, me explaining as best I could what she was seeing for the first time. Those towering scaffolds? They support enormous hydraulic fracturing drills, whose packers plunge the planet like gigantic hypodermic needles. Those constantly seesawing pump-jacks? They keep oil flowing from shale to tank. Those alarmingly random torches, lighting the landscape day and night? Those are what you’ve been hearing so much about: Methane gas flares. And, of course (although this hardly needed explanation): The bumper-to-bumper industrial traffic, its chain of headlights now famously visible from space.

Two solid days of sightseeing and verbal analysis left us mentally and emotionally parched. Even two-for-one glasses of wine at the Buckskin Saloon couldn’t help shake the shock of how deeply the boom has rocked the Bakken. We’d ventured into the bar to escape the din of development. What we found were road-ruddied, beer-gulping guys with oil company emblems on their overalls.

It’s Wednesday now and Liz and I have figured out that we are thirsting for a nourishing taste of nature, something to help wash down all the man-made hustle and bustle. Terry’s got the day off and is behind the wheel of my silver Subaru Forester. Liz and I sit in the back. We’ve been touring the national park for about four hours and are nearing the end of the 14-mile scenic loop that’s carved along the ridge line above the serpentine Little Missouri River. Soon we will be heading back to Killdeer. The sun has started to retreat toward the western horizon; it’s a month before winter solstice and, by 4 p.m. this far north, things begin to darken. We are quiet and meditative. I can’t help but reflect on the contrast between the park’s serenity and what lies ahead on the highway. That’s when the bison at the watering hole come into view.

Photo by Jesse Veeder Scofield.

The largest one turns toward the car—his massive, anvil-shaped head darker brown with much longer fur than the rest of his body—and looks me in the eyes. His are rheumy, cloudy, not bright and clear like the dozens of white-tailed mule deer that have been flanking our movements all day. His shoulders are so hunched, surely it must be painful. But that’s his nature, I’m reminded, a nature that allows him to sprint at 30 miles-per-hour; at least that’s what the sign at the campground said, and if the size of the bison droppings all around were any indication, these fellows are not to be messed with. Good thing this big bull bison isn’t sprinting now, I think: He’d floor us in a flash!

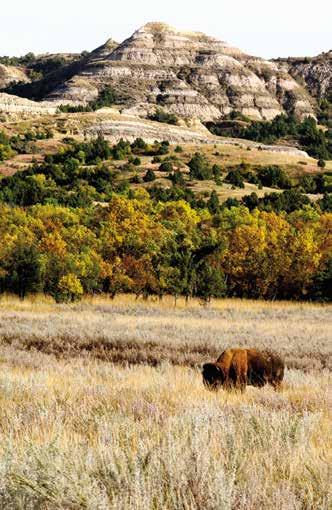

We are at arm’s reach, just a few feet from the watering herd. We didn’t mean to sneak up on them, it’s just the timing of the thing. Dusk has completely descended by now and ours is the only car on the weaving, single-lane road. We’d seen a solitary bison earlier in our drive, soon after having started out. That burly bull was silhouetted against the blinding, pouring, leaning midday sun. I’d snapped a shot because he looked like something out of a coffee table book: The hulking, humpback profile perfectly iconic, from Native American times, from even before that, one has to assume. It was the bison outline that every school kid remembers from history lessons about the Wild West.

But this show of mammalian muscle at the watering hole is different. Perhaps it’s because we are so blissed out from our wildlife overload. Perhaps it’s the unsettling comparison between these bison slurping up earthly fluids while we humans are drilling for different—but just as vital, at least economically—earthly fluids outside the park’s borders. In any case, I’m starting to wonder: Is every day in the North Unit like this? Is there so much wildlife in this relatively small area because development is encroaching on the animals’ natural habitat? Or could it be that these beasts are putting on a sunset show just for us, communicating something that maybe we haven’t yet grasped? After all, that first, picture-perfect solitary bison and those dark-eyed mule deer from earlier were impressive. If we’d witnessed no other animals or birds during our drive through the park, surely our thirst would have been sated. Yet those initial sightings proved to be just a little spoonful, a wee sip of the Nature Preserves we were to be served.

Two hours earlier we’d parked the car at the loop’s midway point. Oxbow Overlook sits high above wide stretches of ancient badlands. Coats zipped against the autumn air, we stepped lightly toward the canyon’s gravelly edge. Layers of colored sandstone and clay, whitewashed by the elements, made it hard to tell at first whether the formations below were flat or rounded, long or square. Our eyes adjusted to the shadows. Outcroppings of shrubbery and rocks came into relief. Gullies and spires, smooth buttes and jagged lines texturized the horizontal still life. The Little Missouri River stitched a winding valley seam down its middle. Above us, a pair of golden eagles rode the thermals, cutting slow figure eights on the cloudscape.

“Shhhh! Look at that!” I whispered. A quartet of bighorn sheep had appeared on the ridge to our left. They postured deliberately, doing their bighorn sheep dance, the dominant male with the largest horns leading a few steps ahead before the smaller three would lift their grazing heads to follow, always on the inside of Mr. Alpha, hugging the craggy drop-off in case a prompt escape was called for.

The three of us froze. Watched. Waited. Minutes passed before the sheep, one by one, began to leisurely disappear from view, picking their way down into the valley.

Photo by Jesse Veeder Scofield.

“Our spirits are on the wing,” Terry said softly, his eyes moving from the sheep to the still-circling eagles. I could feel him next to me, tall, warm, calm, completely sacrificing himself to the moment. I’ve always admired his ability to untether from life’s weighty anchors and float in the unseen realms where the universe performs magic on our souls, waving over us the wand that fills us with sparkling energy, hope and optimism. I’d seen photos of my husband taken in the early 1970s: A long-haired, back-to-the-land hippie, studiously constructing a geodesic dome somewhere in Oregon’s dense Cascade Mountains. (His first child would be born in that dome a few years later.) Even then, Terry possessed an ease in nature’s awesome arena, a palpable and mutual respect between him and the world around him. I squeezed his hand. I felt overcome by good fortune.

On my other side stood Liz, aglow, the sun turning her long golden hair the exact color of autumnal prairie grass, lifting in the breeze. Right then, I envisioned her—coiffed tresses undone by the wind, pouring wildly down the back of her camelhair coat; knee-high black suede boots hugging shapely calves; dark designer sunglasses shading moist hazel eyes—as a strong palomino mare in harness, straining to gallop away yet holding herself in place. Despite her refined urban glamour, it’s apparent that Liz is from this land. There’s no denying it. The wilderness speaks to her, holds her in thrall, a cradling force.

“This is like seeing God,” she whispers, leather-gloved fingers touching her lips. She watches the ram’s curling crown of horns descend into the valley. I sense her forging the scene into a mental talisman that will protect and inspire her for months to come.

For my part, I can’t stop the tears, they just keep falling down my face. No sobs, no sniffles, no coughs. Just tears. A torrent. I imagine myself a giant Jennifer, bigger than anything! I imagine myself stepping off the cliff onto the riverbed below, crouching down, my enormous palm resting on the ground, lowering my large and voluptuous self into repose. First on my side, ear resting on bent elbow, sightline even with the cliff tops, the sheep watching me instead of the other way around. I can almost feel myself laying my cheek in the river, the early winter water so cool, running along my skin. In my reverie, I wet my tongue; the river tastes pure and good.

At that moment the three of us exhale a long sigh, a sigh that melds with the air and forever binds us even more closely together. I am in the middle, still crying, holding the hands of my husband and best friend.

Ten full minutes pass before we gingerly resume our places in the car. Terry turns us around and we begin the sevenmile drive back to the park’s entrance. There is no need to speak. Before long, a dozen longhorn steers amble across the field to our right. I look at them and I realize I am nothing more—and nothing less—than just another magnificent beast in the wild, trekking over the land, feast or famine. I, too, am conditioned to be exquisitely aware of the many obstacles placed in my path by humans and Mother Nature alike. I, too, am skirting oil wells and avoiding power lines in order to make it home alive and well. I, too, drink from this earth.

A putty-colored desert cottontail scurries across the road and vanishes between some sandstone pillars.

Now we are at the watering hole full of bison. Terry brings the car to a slow stop. Our windows are wide open. We share this last golden ray of dusk with the beasts. For a split second, all seems perfectly silent and still. Then the cacophony is revealed: Great grunting and lapping, heavy wheezing and coughing. Surface ice bursts and crackles under the bisons’ hooves and against their legs. They slosh around, kicking up shallow, muddy water. Long ropes of wet brown fur whip back and forth from their soaking chins. I see steam coming out of the bull’s nostrils as his body’s hot air meets the winter-chilled pond. I remember the collective sigh that Terry, Liz, and I had all let out half an hour earlier and I visualize these beasts breathing in some of the air that was once inside of us. I’m swimming again in this profoundly simple reality—the oneness of nature—when I turn away from the drinking bison. There’s movement ahead, big and dark.

On the side of the road about thirty feet in front of us lumbers another bison, up from the ditch beyond. She’s heading our way. (For some reason, I assume it’s a cow, she’s practically petite next to the bulls we’ve seen.) Then a second bison appears, then a third, then a fourth, then two more before the granddaddy of them all hauls himself up over the edge onto the road and slowly, wholly unperturbed, pushes this bison parade forward. We have clearly parked smack in the middle of watering time and the entire herd is meeting for Happy Hour.

“It’s a traffic jam of bison,” says Liz, finally breaking our human quietude.

“It’s a bison jam!” I say. “And we’re invited.” Everyone’s thirst is quenched.

Jennifer Strange is a newspaper and magazine journalist whose articles and photographs have won numerous Alaska Press Club, Inland Press Association and Suburban Newspapers of America awards. She holds degrees in journalism and English from the University of Kansas and is currently earning a Master of Fine Arts in nonfiction writing through Pacific