13 minute read

"Hard Work and Much Fun”: A North Dakota State of Happiness

by Debora Dragseth and Stacy A. Cordery

North Dakota has a problem: a serious brain, brawn, and creativity drain. North Dakota suffers the highest net outmigration of 18-to- 25-year-olds than any other state in the nation. The statistics are sobering. In both 2009 and 2010, North Dakota ranked second on Forbes “Worst States for Keeping College Graduates” list. According to the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, for each one hundred graduates with bachelor’s degrees produced annually in North Dakota, 71 of them will leave the state. Only 37 bachelor’s degree holders (ages 22-64) will enter, resulting in a net loss of 34. The loss of so many vibrant citizens carries incalculable costs, and the reasons for their departure may be rooted in the very traits North Dakotans hold most dear. State historian Elwyn Robinson described them in his seminal book, History of North Dakota, as “courage, optimism, warmhearted neighborliness, energy, individualism and self-reliance.” Theodore Roosevelt would have agreed. The people he met here were suffused with those qualities—they are what caused him to fall in love with North Dakota, and today they play a role in driving young people away.

Advertisement

A young Theodore Roosevelt.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S JOURNEY

Like so many Dakotans over a century ago, Roosevelt was first an “in-migrator.” He was born to a very wealthy New York family in 1858. Even before he matriculated at Harvard College in 1876, he was a recognized as an expert ornithologist. An avid reader, he was a hunter, a taxidermist, a naturalist, and extremely fond of the outdoors. But he was also puny, undersized, sunken-chested, asthmatic, and nearsighted.

At Harvard, he fell in love with a beautiful Bostonian named Alice Hathaway Lee. They were married on his twenty-second birthday in 1880 and, a year later, he entered the New York State Assembly. In the autumn of 1883, he came out to the Dakotas.

In so doing Theodore Roosevelt joined a larger American phenomenon. The federal Homestead Act of 1862 opened up the West by granting settlers 160 acres, provided they lived on and cultivated part of the land for a set time.

As TR matriculated at Harvard, the Northern Pacific Railroad aggressively began to recruit settlers by mailing pamphlets in English, German, and other languages touting the great possibilities in the Dakotas. Advertisements packed the pages of American, Canadian, Scandinavian, and German newspapers. Thus enticed, people came eagerly and the Great Dakota Boom of 1878 to 1890 began.

The Dakota boom caused the northern territorial population to increase from 16,000 to 190,000. In 1890, when the frontier was declared officially closed, 43 percent of the state’s inhabitants were foreign born. Western North Dakota was still the Wild West of Indians, cowpunchers, buffalo hunters, saloon rats, and outlaws. The land played, as it still does, a central part in the story of western North Dakota: blazing hot summers, blinding blizzards, miles of grassland punctuated by abrupt bluffs and buttes, magical sunrises and sunsets, long winding rivers and endless open spaces.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Maltese Ranch Cabin.

Theodore Roosevelt arrived at the start of that boom. He came to kill a bison. He took the Northern Pacific nearly all the way to the settlement of Little Missouri.

There was little to see when TR arrived and Medora, the “town” across the river, had only been founded five months earlier, in April 1883. There wasn’t much there, either. Like the hero in many Western tales, TR was totally out of place in his new surroundings. But Roosevelt wasn’t after civilization. He was gunning for a buffalo.

It took him ten long days of nearly constant cold, driving rain, Badlands mud, and missed shots. He was freezing. He was wet. He was riding tough miles and sleeping on hard ground. He was thrilled. This was living! It was nothing like his “effete” Eastern existence where he was protected by money and coddled by his relatives, where he had every comfort his inheritance could buy. This was the sort of adventure only real men could endure and appreciate. He was so enthused, happy, and imbued with the spirit of the place that he embraced its potential and bought $14,000 worth of cattle and the Maltese Cross Ranch. He began to consider seriously a career as a Dakota ranchman.

After 18 days, he had to return to his pregnant wife. Five months later, she and his mother both died on Valentine’s Day in 1884. In shock, TR wrapped up business in the legislature, gave his newborn daughter to the care of his sister, and returned to the Dakotas to mourn.

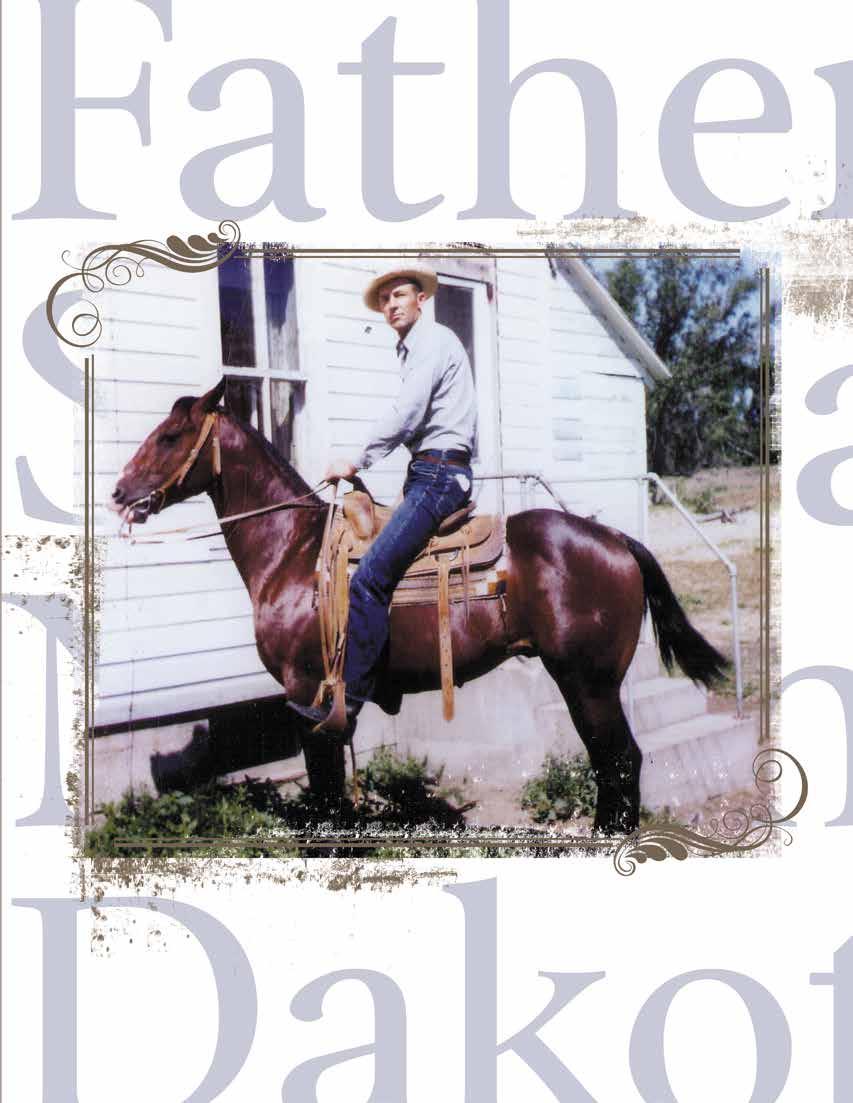

Theodore Roosevelt with his horse.

He arrived back here in June of 1884. Needing more quiet than the Maltese Cross could offer, he bought the Elkhorn Ranch, 35 miles north of Medora. He hunted. He avoided a duel. He punched out a drunk in a bar. He brought thieves to justice. He participated in cattle drives. He survived a midnight stampede during a thunderstorm. He injured himself. He wrote.

In his terrible grief, it’s as though he had to throw himself against a force as strong as death. Everything Roosevelt did in North Dakota, he did to an extreme… and the countryside, the weather, and the experiences of Westerners matched his desperate and stricken state.

“I do not believe there ever was any life more attractive to a vigorous young fellow,” Roosevelt recalled, “than life on a cattle ranch in those days. It was a fine, healthy life, too; it taught a man self-reliance, hardihood, and the value of instant decision—in short, the virtues that ought to come from life in the open country. I enjoyed the life to the full.” He loved the doggedness of the people, the critical nature of the work, the majestic scenery, the opportunities. “We knew toil and hardship and hunger and thirst…but we felt the beat of hardy life in our veins, and ours,” he proclaimed, “was the glory of work and the joy of living.”

What Theodore Roosevelt appreciated in North Dakotans was their courage, their physical lifestyle, their persistence, their ability to shrug off danger, their calm and nondramatic fashion of taking life in stride, their facility with horses, cattle, guns, and knives, their independence—but also their ability to come together in community when the need arose. His experiences here became the basis for his strenuous life. He would say his political success rested on what he learned in the Dakotas.

North Dakota shaped Theodore Roosevelt. Here he cultivated an inner strength he suspected he possessed but had not been adequately tested. If the cold winter of 1886-87 had not killed off the majority of his herd, there might have been a different ending to the story of TR in the Badlands.

But his time here provides a mirror for North Dakotans. We can peer into the past to see an extraordinary man who lived and loved this western life. He preached the importance of the strenuous life and criticized the choice to live without toil or danger. North Dakotans today take pride in the same qualities of perseverance, self-reliance, and pride in hard work.

But are these traits, dating back to the settlement of this territory, still valued today? Is hard work still considered exciting and fun? What do generational changes have to do with the prevailing perception of young people that a better life is to be found outside the borders of this state that Roosevelt loved? Do North Dakotans today believe that happiness lies somewhere else?

A STATE OF HAPPINESS

For the last three years, the Gallup organization has called 352,000 randomly selected American adults between January 1 and December 31 (1,000 people a day) and asked them about their quality of life. Responses are then converted to Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index, a part of Gallup.com’s massive project “State of the States,” the most comprehensive study of its kind, revealing state-by-state differences on political, economic, and well-being measures. One of the questions in the poll is, “Did you experience feelings of happiness during a lot of the day yesterday?” Ninety-three percent of North Dakotans said “yes,” ranking the state third on the well-being or happiness scale and trailing only Hawaii and Wyoming. We rank an impressive number two in emotional health, barely edged out by the number one state, Hawaii. As the folks at Gallup acknowledged, “Sun and waves might be good for the soul—but the sunshine doesn’t necessarily elbow out Northern Lights and snow.”

Happiness is an enduring sense of positive well-being, an ongoing perception that life is fulfilling, meaningful, and pleasant. Science tells us this about happiness: Marriage makes people happy, but children don’t. Youth and old age are the happiest times in our lives. Globally, teenagers are the happiest people. And, of course, money doesn’t buy happiness.

Yet, these are simply generalities; happiness is not one-size-fits-all. Some of us are happier after our marriages end, or the happiest times in our lives might be in our 30s or 40s. With the utmost certainty, however, all of the research tells us one thing: happiness is a choice.

Neuropsychologist Dr. Rick Hanson believes, “We can actually use the mind to change the brain. The simple truth is that how we intentionally direct our attention, embrace positive experiences instead of negative ones, it will alter the brain’s structure.” Much of what changes us is our experiences. Theodore Roosevelt certainly had never read the research, but he intuitively knew that he needed to be among North Dakotans and in the singularly beautiful Badlands in order to rediscover his happiness. As Hanson emphasizes, “What flows through the mind actually changes and sculptures the brain.”

If any of us could live our life over again, what might we do differently? In studies of people older than 95, three answers surfaced time and again. They would 1) reflect more, 2) risk more, 3) do more things that would live on after they were dead. Although he only lived to his early 60s, Theodore Roosevelt surely hadn’t any of these regrets.

So, given that North Dakota consistently ranks as one of the two or three happiest states, why do so many of its young people “escape” at their first opportunity? Demographers who study outmigration note that high school graduation and college graduation are the two key exit points. Researchers David Schkade and Daniel Kahneman surveyed 1,993 college students in the Midwest and southern California, asking them to rate their overall satisfaction with life. The researchers found that the two groups were nearly identical in their self-reported life satisfaction. However, when they were asked whether Californians were happier than Midwesterners, both groups consistently reported that Californians were happier. The researchers posited that “it is not unlikely that some people may actually move to California in the mistaken belief that this would make them happier.”

North Dakota hit its peak population in 1930 at 680,845. But that’s not at all what observers thought would happen. Early twentieth-century forecasters expected North Dakota’s population to expand to two million people, of whom 200,000 would be farmers. At an average family size of five, there would be one million total people on the farm with another one million living in cities and towns. The 2010 census counted 672,591 North Dakotans. Today, the state’s overall population is not declining; however, the population is consolidating and aging. Data gathered by the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation predicts that by 2012, the number of people age 65 and older will surpass the school-age population in North Dakota. And by 2020, nearly half of the counties in North Dakota are expected to have fewer than 4,000 residents.

College seniors tend to believe that life in North Dakota is harder than elsewhere and that by leaving, they will be happier. A full 33 percent of them—all native North Dakotans—insist they will definitely leave the state after graduating, one-third indicate that they will definitely not leave, and one-third are unsure. Those who intend to out-migrate believe their choice will make them not just happier, but wealthier and more fulfilled. Phrases like, “I am anxious to leave and experience bigger and better things,” and “I am leaving to start a career with more opportunities” pepper the comments of seniors who intend to leave the state.

Yet, North Dakota boasts five main positive characteristics, even for those readying to depart. The seniors treasured the comfort and safety of North Dakota, the fact that there is less competition here, the friendliness of the people, the proximity of family, and the shorter commutes to jobs. But there were five negatives that weighed more heavily. In North Dakota, they believed they faced a lack of opportunities for advancement, low pay, a relative absence of technology, brutal weather, and a signal lack of social activities such as concerts, sporting events, and varied venues for nightlife.

SHOULD NORTH DAKOTA CHANGE?

Does North Dakota need to change? Or, do we simply need to readjust the internal as well as external perception of North Dakota as a difficult place to live where people couldn’t possibly be happy? Ron Wirtz, editor of the Minneapolis Fed’s newspaper, recently wrote that “Unemployment is 3.7%, and according to a Gallop Survey last month, North Dakota has the best job market in the country. Its economy sticks out like a diamond in a bowl of cherry pits.” Yet, for every piece of good news, there seems to be a counterbalance in the national press. Richard Rubin wrote disparagingly in the New York Times that North Dakota is “as you might imagine it: Vast. Open. Stark. Mostly flat. All but treeless, Above all, profoundly underpopulated, so much so that you might at times suspect it is actually unpopulated. It is not. But it is heading there.”

Whether we alter perception or reality, change is difficult. As famed North Dakota pundit and former lieutenant governor Lloyd Omdahl stated in his Bismarck Tribune column, “Unless we are under great economic stress…North Dakota plods along in the wagon tracks of our predecessors.”

Yet, if we can’t retain our young leaders today, when will we ever have a better chance? Let’s look to our mirror. What might TR have to say to young North Dakotans today? Perhaps he would repeat the words he offered in 1898 to a group of schoolchildren in Oyster Bay, New York: “There are two things that I want you to make up your minds to: first, that you are going to have a good time as long as you live—I have no use for the sour-faced man— and next, that you are going to do something worthwhile, that you are going to work hard and do the things you set out to do.”

Nature and remoteness are not seen as the twin enemies for those who find their happiness in western North Dakota. Perhaps, as TR found, closeness to nature and the land, doing something useful and leaving a legacy are the things that are necessary for peace within. The pursuit of happiness beckons us all, but it shouldn’t beckon our youth away from North Dakota.

Debora Dragseth is a professor of business at Dickinson State University. She is an active speaker on the topics of leadership, outmigration and Generation Y. Dragseth develops leadership curriculum for Fortune 100 companies and has been a recent contributor to New Geography, India Times, CNN.com and MSN.com. Her work on outmigration has been cited in both Forbes and Newsweek magazines.

Stacy A. Cordery, a professor of history at Monmouth College in Illinois, is the author of the recent biography and New York Times Notable Book, Alice: Alice Roosevelt Longworth, from White House Princess to Washington Power Broker. Her newest book, Juliette Gordon Low: The Remarkable Founder of the Girl Scouts, was published in February 2012. In the spring of 2011, Cordery served as the first Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University.