10 minute read

Eating with Eyes on the Community

Photos by Sarah Smith Warren, www.sarahsmithwarren.com

by Dean Hulse

Advertisement

I recently came across a note I’d dashed off some time ago that concerned an advertisement (circa 1922), which I’d seen in my hometown newspaper. If memory serves, I’d been looking through newspaper archives while doing research on a topic unrelated to the ad’s subject, but its copy nonetheless caught my attention. The ad read, “Butter and Eggs, same as Cash.”

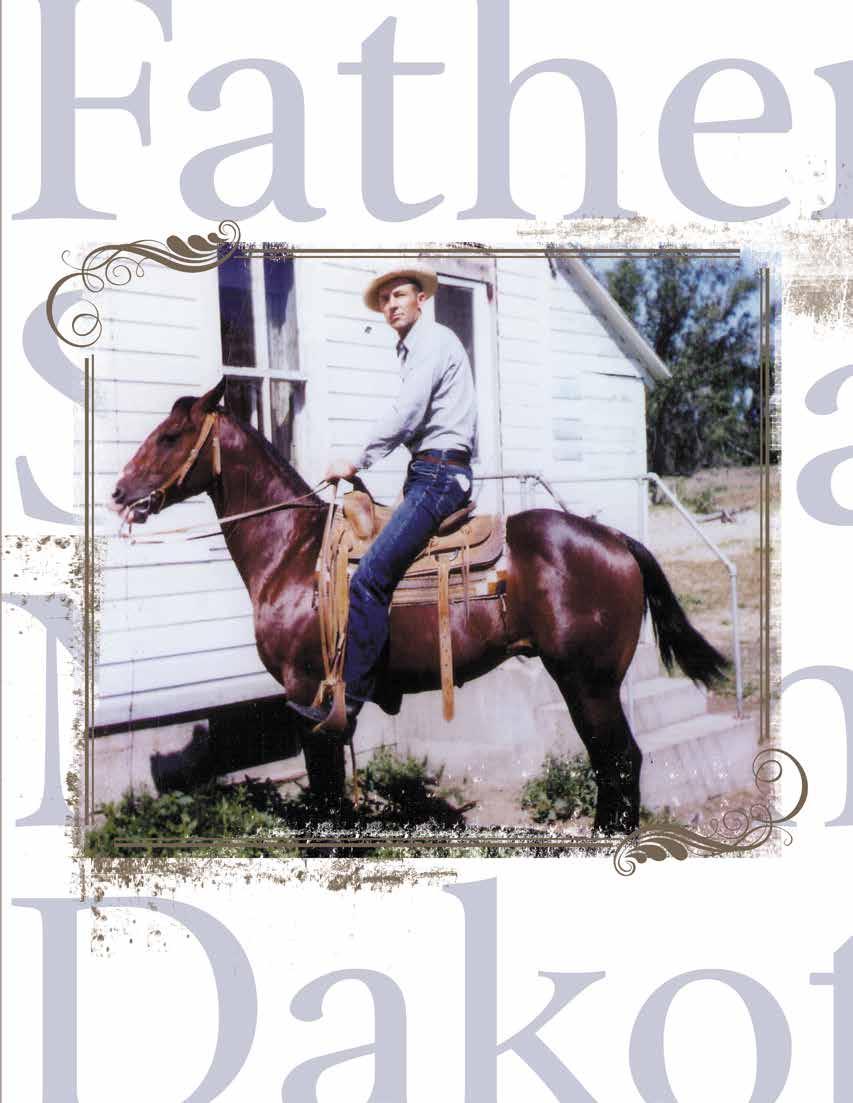

My maternal great-grandmother and my grandmother both bartered butter and eggs (and cream) for staples, probably with the same grocer who ran that ad in my hometown newspaper. According to family legend, my maternal great-great-grandmother was a “fancy cook” in England before she and my great-great-grandfather emigrated first to Canada and then to Richburg Township in North Dakota’s Bottineau County.

Mom was an exceptional cook, too, so perhaps it’s genetic. Even as a child I experimented in the kitchen, and Mom and Dad were generous with what they allowed me to make. Like many farm families of that era, our “fruit room” resembled a grocery store—with shelves full of jams, jellies, tomato sauce, green beans, relishes, and pickles (beet, cucumber, corn, cauliflower). Also, canned stew meat and meatballs, with congealed morsels glistening like jewels inside the jars. Without asking, I could go down to the basement and retrieve a package of frozen hamburger, wrapped in white freezer paper carrying the “Not for Sale” label our local butcher had affixed. The beef came from our own steers. My first food triumph was sizzling as Dad arrived for dinner: hamburgers, releasing the aroma of nearly every dried herb and spice Mom had in her cabinet. A predominance of chili pepper, onion salt, and garlic powder gave these burgers a piquancy that perfectly complemented a melting slab of Colby cheese.

Of course, I had a few failures. A sodden tuna pizza comes to mind. A meal fit for our dog Stub, who required some persuasion.

“You eat that,” I barked.

I’ll end the tales of my adolescent cooking escapades here.

Beside my note containing the “Butter and Eggs” ad copy, I’d scribbled my reaction: “Oh really? Try making a cake out of cash.” I know about cake. Dad’s avocation was baking angel food cakes, each requiring fourteen egg whites, and many of which he gave as gifts.

Butter and eggs, same as cash? I know bartering is a form of commerce, but during my life, I’ve witnessed this butter-and-eggs sentiment assume a more literal character. I don’t think it’s a stretch to claim that many who frequent supermarkets today behave as though their cash is the same as cabbage, one indistinguishable commodity exchanged for another. For many years, I was one of those shoppers.

When my wife, Nicki, and I first moved to Fargo, I relished the fact that I could shop at grocery stores overflowing with exotic produce at 3 a.m. if I so chose. Like many Americans, I ate daily, and well, without knowing or caring a lick about the food on my plate—except how it looked and tasted, and perhaps how much it cost.

For me, the convenience of that marvelous arrangement helped blunt some repulsive memories of growing up on a farm. Picking eggs as a child was a chore, especially when I’d encounter an unexpected visitor in the henhouse. I once discovered a large rat, sitting on its haunches, exposing an oozing ulcer on its underside. After retracing my steps, lickety-split and empty-handed, back to our house, Dad returned with me to the clucking chickens. That rat departed this world squirming on the end of Dad’s five-pronged pitchfork, creating a silhouette against the early morning sun.

And so, I was OK buying anonymous eggs produced who knows where. But in my late twenties, my outlook began to change. I don’t think genetics was responsible. More likely, it was modeled behavior—that is, my having grown up with gardening parents and my having experienced truly fresh food. What manifested my latent craving for vine-ripened tomatoes? I can’t say. What satisfied it? Thick tomato slices still conveying the sun’s warmth, made even more perfect by salt, pepper, mayonnaise, and two slices of bread, substantial enough to absorb the free-flowing tomato juices without becoming soggy. A summertime sandwich to savor for only a few weeks, but to anticipate the rest of the time.

At first, we rented garden plots from the Fargo Park District, and we drove to our garden with open buckets of water sloshing in our car’s trunk. Later, I bought a small trailer and adapted it so it could haul two fifty-five-gallon water barrels. One year, someone stole our entire crop of spaghetti squash. I pacified my anger by writing a letter to the editor of our local newspaper, in which I offered a recipe so that our thief could fully enjoy his booty (his—large footprints among our picked-clean squash vines). A day after the letter appeared, I got a call from a woman living in Casselton. She offered to share some of her spaghetti squash with me. Another woman from Moorhead did the same. We ended up with more spaghetti squash than we had growing in our garden.

That series of incidents planted a seed that would sprout once we bought a home and had a garden of our own. Now, we didn’t start our backyard gardening with the altruistic notion of supplying our neighbors with produce. But on most years, there are only so many zucchini squash two people can eat. To our credit, we are diligent in checking our zucchini plants. We aim to pick the fruit when it’s six to eight inches long, and that’s what we share with neighbors. Those zucchini lurking at the very bottom of our plants, the ones stealthily growing to the size of small children’s legs, we toss into our compost pile.

We also share tomatoes, eggplant, onions, spinach, chard—whatever we have in overabundance. Our neighbors have been joyfully generous with their in-kind reciprocations. One of our neighbors, an elderly Japanese widow, treats us to several meals reflecting her culture’s cuisine each year. Painstakingly garnished and with precisely cut vegetables, her dishes don’t disappoint in presentation, taste, or texture. I often daydream about her sticky rice. And the source of her homemade herb wine, which packs a punch more like a liqueur, grows right outside her garage service door. This year she’s going to show us how to grow the herb and make the wine.

Another neighbor is the patriarch of a family-owned package store and popular college bar. He repays with wine or beer, some of which comes to us with a “born-on” date that is either current or only a day or two old. A Montana native, he’s also shared cherries that grow near Flathead Lake.

Our neighbor to the south loves our rhubarb. And we love her rhubarb pie, made distinctive by the fresh orange zest she adds. I’ve been known to eat three pieces of this pie at one sitting. The neighbor whose backyard is full of fruit trees lets us pick his cherries, apricots, and apples until our hearts and our appetites are content. While it takes many hours of picking and pitting, with me picking and Nicki pitting (the really hard job), our collaboration has resulted in a cherry jam that I have thought about in the middle of the night. We’ve dehydrated the apricots for a tart addition to our oatmeal. And while I can count on one hand the number of pies I’ve baked, I did a pretty good job of creating a three-inch-high apple pie for one of Nicki’s birthdays.

Butter and eggs, same as cash? Sharing our garden’s bounty has taught us much about bargains, by which I mean the unspoken agreements that we’ve forged in our neighborhood. For the most part, these bargains have been organic, in that all of our contributions fit together harmoniously, as necessary parts of the whole. We feed each other, but we also nourish each other with meaningfulness that sustains our friendship. We’ve formed a network that pulls us tighter than could our geographic proximity alone. Our exchanges of fruits, veggies, and other goodies have created social capital, and I’d be hard-pressed to estimate its cash equivalent.

While we’ve developed our gardening abilities, we’ve also assumed responsibility for carrying on family traditions, both mine and Nicki’s. One of mine is plum pudding, a Christmas custom dating back to my maternal great-great-grandmother, the “fancy” cook. Plum pudding is steamed and among

its ingredients are breadcrumbs, chopped walnuts, dried cherries, diced apple, and suet—beef fat. We’re able to get our suet from the same person who supplies us with our organically certified grass-fed beef. He doesn’t sell the suet, but the last time I asked, he saved some and gave it to us. No charge, which is mighty neighborly.

Representing Nicki’s side of the family, we’re now the makers of lefse, horseradish (which we grow), and sauerkraut. Because we don’t want to take up the garden space required to grow enough cabbage for our kraut, I needed to find a supply, so I visited a local farmers’ market. Each August, I buy one hundred pounds of cabbage from the same farm marketer. This year, I’ll have bought cabbage from him for twenty-five years, a silver anniversary of sorts.

There are now nearly forty farmers’ markets operating across the state with support from the North Dakota Farmers Market and Growers Association. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports a 16 percent nationwide increase in the number of farmers’ markets just between 2009 and 2010.

Meanwhile, the concept of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) is catching on, too. Typically, CSA members pay in advance for a share of a farmer’s produce, which he or she will deliver by the boxful each week during the growing season. The advance payment covers the producer’s anticipated costs and salary and thereby allows members to share in the risks and rewards of growing local food.

Many people I’ve talked with say they frequent farmers’ markets or join CSAs because they want to buy food grown closer to their homes. The food is fresher, with all the extra flavor and nutrients this freshness implies. They also get exposed to new fruits and vegetables and new ways of cooking, they learn how food grows, and they can meet the people who grew their food. Many visit their CSA farm once a year or more.

All of those reasons make sense to me. While our industrialized food system may be efficient in some respects, it is nonetheless dependent on fossil fuels throughout every phase—growing, processing, and distributing. We’re saving energy by eating whole foods raised locally. Also, our globally intertwined food system means food-borne illnesses can spread across the country in a matter of days, as outbreaks of E. coli and salmonella poisonings prove.

There are unexpected pleasures that come from buying locally, too. Once when I was standing in line to buy cabbage from my farm marketer, an elderly woman ahead of me in line struck up a conversation. Without any prompting and without any apparent cue, she began telling me about the watermelon of her childhood. She told me that her dad would bury ripe watermelon in the wheat stored in their granaries. The wheat was warm enough to keep the watermelon from freezing. She said they’d be eating watermelon well into November during most years. I can only imagine what a treat it was.

After reflecting on our own local food experiences the past quarter century, I’ve concluded that the grocer who placed the “Butter and Eggs” ad in my hometown newspaper nearly a century ago was right to exchange his merchandise, like cash, for eggs and butter coming from someone he knew, from someone whose farm he could visit. I’ve also decided that while we still can’t make a cake out of cash, we can build a community out of fresh food.

Dean Hulse is a writer living in Fargo. He and his wife, Nicki, still own his family’s farm in Bottineau County, which is a source for much of Dean’s activism and inspiration concerning land use, renewable energy, and sustainable agriculture. In 2009, the University of Minnesota Press published Hulse’s memoir, Westhope: Life as a Former Farm Boy.