10 minute read

Reading and Rereading Eric Sevareid

By Mark Strand

I have never quite grasped the worry about the power of the press. After all, it speaks with a thousand voices, in constant dissonance. -Eric Sevareid

Advertisement

While veterans of the last war were unpacking their footlockers in 1946, Eric Sevareid’s Not So Wild a Dream suddenly appeared in their living rooms, making its way as a bestseller. Like the kid on the block who succeeds at door-to-door sales, Sevareid’s “first born” left the house without so much as an introductory note from its parent to warn readers what the book was up to.

To people in the book trade, Sevareid must have seemed myopic about marketing. The following were also absent from the book: a preface by a famous person, or one of the author’s pals, to confer status and boost sales; chapter headings with names instead of numbers (the author was taking the reader on a tour around the world; signposts might help). There were no photos, and the author’s biographical sketch was missing. Not So Wild a Dream would only state its name up front and say that the CBS writer Norman Corwin had thought of it first. Then with a swoosh of italic type, To L.F.S., the book was off and running.

Eric Sevareid was used to jumping into a story, and he was hell-bent on getting to page one, scene one with this first sentence: “The small brown river curved around the edge of our town.” Readers were then swept away by a narrator who brings scenes to life, as vivid as film, and lays his thoughts over the images. Simultaneously, the reader is inside the action and the mind of the author. A river of film runs through Sevareid’s book: his childhood in North Dakota, his 2,000-mile canoe trip with his friend Walter Port, riding cross-country in boxcars, working a newspaper beat, attending the University of Minnesota, and starting a family during a war while circling the globe as a CBS correspondent.

Here is Sevareid’s “short film” about France on the brink of war:

“They were coming from the slums and tenements, and they still had on their soft, powdery denim, their working clothes. From the elbows hung the oval helmets they had kept in the back closet since 1918. They did not look like soldiers beginning a war; they looked like soldiers at the end of a war, when soldiers resemble any other tired men. Their wives had come with them to the station, hanging to their arms, shuffling rapidly in their felt slippers to keep up with their men. Their hair was pinned carelessly in place, and their eyes had the dry glaze and coloring that signified all-night weeping. They waited for the trains, standing facing one another, oblivious of anyone else, the husband staring over his wife’s head at the floor, the wife staring at his chest, and neither speaking. A tall, handsome young officer with shiny dark straps was grinning at his fashionable wife, pretending to sock her in the jaw, kidding her. Form. A behavior pattern. Noblesse oblige. The poor, who struggle for daily bread, have time only for reality.”

Inside his river of film, Sevareid sometimes pauses to make powerful word pictures. While Germany invaded France, and Lois Sevareid lay in a French hospital about to give birth to twin boys, Eric stopped in the middle of the French retreat, looked back, and painted his famous visual metaphor of Paris as a woman lying in a coma slowly bleeding to death.

Then the action continues with rapid transitions in and out of scenes woven together with Sevareid’s thoughts about people and nations. He is just as interested in a tribe of Naga headhunters in the Burma jungle as he is European societies. A conscientious guide, Sevareid is so anxious to take the reader inside scenes that we sometimes lose sight of him. As one of his reviewers wrote, Sevareid “uses autobiography not as a memorial to self but to enrich the common experience.” Similarly, encounters with his family are veiled and nearly off camera. The reader may stop several pages later and ask, “Was that Eric’s brother he just met on the street in Paris?” or “I wonder how Lois and the twins are?”

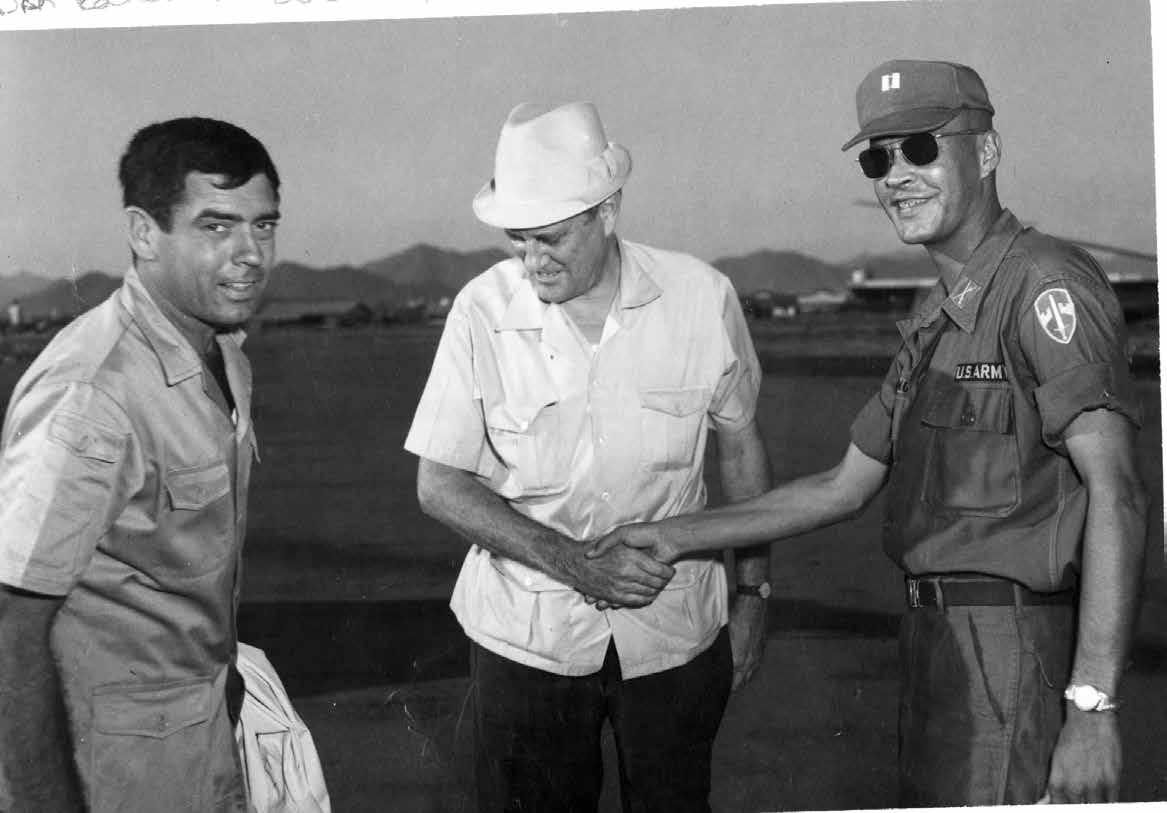

Eric in the Burma jungle, early 1940’s.

Mark Strand is a professor and chair of mass communications at Minnesota State University Moorhead. He grew up in a family-owned photography business in Rugby, North Dakota, and graduated from Concordia College where the president of the college told his parents, “He’s a little liberal, but he’ll be all right.” Strand did his graduate work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. war had ended? Memoirs this complicated take years to research and write, and some gifted writers never get the job done. How did he have the courage to write so openly about his thoughts and beliefs? The cold war was coming on. How would CBS and its sponsors respond to his candid thinking? What about the House Un-American Activities Committee or J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI? His only expressed concern was his fear that the public would count him among those who “lost China” due to his frank reporting about Chiang Kai-shek’s weak, corrupt regime.

THE NEW EDITION Thirty years after its birth, Not So Wild a Dream was a grown-up. The book had ranked high on the bestseller lists and survived eleven printings without changes, including no word from the author in the form of an introduction. Then in 1976, a year before his retirement, Sevareid stepped from the shadows like a proud father to explain the mysterious birth of his book with a proper introduction to a new edition. He would also talk about his approach to writing and reveal more about himself. The content inside remained unchanged because, “self-protection of that kind would appear dishonest.” The new dust jacket wore the subtitle: “A Personal Story of Youth and War and the American Faith.”

About the birth of the book, Sevareid said that the 250,000 words were written at “one sitting,” in an approximate eight-month window, a happy time for his family between the war and his return to CBS. He had been twice the age of many young soldiers. Now he was young by authors’ standards, his energy equivalent to an “overcharged storage battery.” The book was written from memory with few notes or diaries and sent out without an introduction because “books should be self-explanatory and require no preparation of the reader.” There was little time to reflect on what he had done before getting back to earning a living.

He was proud that the book had become an “original source” for the events to which he was an eyewitness. He was pleased that another generation found it relevant and amused by the readers who wrote to him with “genteel excitement” after discovering his book in antique shops. Speaking of “errors of commission,” Sevareid sounds as proud as a parent whose kid has nearly perfect teeth when he admits to one misspelled word and a misnamed river in Russia. His only technical regret: using “which” when “that” would “fall more gently on the ear.”

Concerning the craft of writing, Sevareid describes the “blessing—or the curse” of his “double vision,” and the process of combining thoughts with actions. The double vision technique calls for 1.) describe the scene (early morning: tired men in work clothes, their wives in slippers, hanging on the men’s arms, making their way to rail station), 2.) locate a person (an officer in dress uniform standing with his stylish wife), 3.) present an idea (contrast the romance of noblesse oblige with the reality of the poor).

Sevareid had discovered that he wrote for the eye, not the ear. There was “not much conversation in the book,” and he didn’t think he was cut out for writing novels. There had been talk of movies. Hollywood wanted to re-tell Eric’s story about his encounter with the Naga headhunters after a plane wreck in the Burma jungle, but India’s Nehru

was busy putting down the rebellious Nagas, and nothing came of it. Thirty years later Sevareid was still angry about Nehru’s treatment of the Nagas—and the abrupt ending to his film.

Filmmaking and writing are not as easy as one, two, three. Behind the scenes are emotions. For Sevareid, emotions were mostly kept in check. He admits to an “impersonality in his personal narrative” and says he was “too young to handle intimacies in public view.” His authorial attitude was “One did not impose his deepest emotions upon others and certainly not upon strangers.”

This attitude about privacy was acceptable in the age of Jefferson but not in 1976. Some of Sevareid’s friends, and many of his readers, wanted to know why he had said so little about his first wife Lois in the book. He acknowledged Lois’s importance and went on with a painful explanation of why their marriage of nearly thirty years had ended. Then he offered this confession:

“The fantasy grew in me that her last chance for health lay in my departure as well as my own last chance to feel again, to see again with the poet’s eye and perhaps, one day, to write something that would be more whole than the writer. I never did, in spite of the departure, of course, and of course she never found health. She endured her own far greater tragedy for a quarter century in all and then died with merciful speed.”

After a lifetime of condensing what he had seen and thought into words, first in print, then five-minute radio essays, and finally two-minute television commentaries, Sevareid was working inside fifteen pages to write something “more whole than the writer.”

In the rest of the introduction, he discusses how America and the world have changed since 1945. The man a friend called a “hundred proof American” expresses faith in his country: “We are a turbulent society but a stable republic;” his profession: “No other great power has the confidence and stability to expose and face its own blunders;” and his countrymen to whom he wished his best: “Freedom is the condition of feeling like one’s self.”

READING ERIC SEVAREID One of the charms and benefits of midwestern libraries is the number of first edition books still on their shelves. I was fortunate to find the original 1946 edition of Not So Wild a Dream in mine and was so entranced by the book that I put down a series of murder mysteries by a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist to read Sevareid’s autobiography.

I wanted to know more. I had only known Sevareid as the man who propped up the CBS Evening News for two minutes each night with nothing but a rock-solid shot on one camera and thoughtful words. Raymond Schroth’s The American Journey of Eric Sevareid, so beautifully written and researched, was just the ticket. Later I purchased my own used copy of the new (1976) edition of Not So Wild a Dream and was surprised to find the “missing introduction.” Now I had something to offer the other member of my two-man Eric Sevareid Book Club, the North Dakota State University photographer, Dan Koeck. As a patron of another library specializing in first editions, Dan valued the new information, but we both agreed that it we were better for being for being deprived of the latest edition, that we had experienced Not So Wild a Dream the way the author had intended.

My interest continued as I pursued other Sevareid books no longer in print. This Is Eric Sevareid, a book comprised of his longer pieces that appeared in various printed publications, includes his essay for Collier’s, “You Can Go Home Again,” helps answer the question, “What did Sevareid see in Velva?” The fascinating interviews Sevareid conducted with notable Americans, ranging from the elite journalist Walter Lippmann to the longshoreman and philosopher Eric Hoffer, have been collected in a book titled Conversations with Eric Sevareid. Reading those conversations sheds light on Sevareid’s remarkable ability to see several sides to a question.

To my surprise, I found Small Sounds in the Night (1956), a collection of Sevareid’s CBS radio essays, on-line. Once the property of the Kansas City Public Library, the book was hiding out on the Internet in both the pdf and e-pub formats. Sevareid liked to grouse about changing technologies, but he might be pleased by how well his printed radio essays translate to new media. It is not so wild a dream to assume that someday we may read his essays on an e-reader with the option to listen to them in Sevareid’s distinctive voice, and no doubt, the package will include the optional video.