24 minute read

ALBERT KOTIN SPACE INTERWOVEN

CHRISTA NOEL ROBBINS

In 1959 the art critic Harold Rosenberg was asked to write a profile of the “artist block” that was located on East Tenth Street between Third and Fourth Avenues in Lower Manhattan.1 Rosenberg, who referred to this small area as an “art colony,” lived on East Tenth himself, alongside a good number of the artists who would come to make up the so-called New York School of painting.2 At the open of Rosenberg’s little geography is a photographic insert featuring several of these artists. The first listed is “Al Kotin” (fig. 1). All the artists, pictured in full-body portraits, stand in or exit from the entryway of their buildings, reinforcing Rosenberg’s claim that this is a community made up of individuals. Joining Kotin in the spread are well-known names: Michael Goldberg, Willem and Elaine de Kooning (pictured separately), Joan Mitchell, and Milton Resnick, among others. Kotin’s name is less familiar today, and this despite being at the center of this burgeoning avantgarde community. Albert Kotin (1907–1980), whose family relocated to New York City from Minsk, Belarus in 1908 when he was just one year old, was an exemplary New York School painter in many ways. A student of the German-born American painter Hans Hofmann, an exhibitor in the generationdefining Ninth Street Show, an early member “the Club”—a social club that brought together artists, critics, and scholars—and, of course, a resident of East Tenth Street, Kotin was in every way a full participant in one of the most influential art movements in the history of the United States. Kotin’s art education started out early with his joining the Art Students League at the age of sixteen and going on to study at several prestigious art schools in Paris. Like many of the artists associated with Abstract Expressionism, which was a slightly more controversial name for the New York School, Kotin was employed for a short time in the early 1930s with the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) under the auspices of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Like Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning, Kotin was in the murals division. While in this program Kotin was offered the chance to execute his own murals at New York University and in post offices in New Jersey and Ohio, all of which were done in the social realist style common to these public works projects. Kotin fondly recalled the “feeling of closeness among artists” during his days as a PWAP muralist, indicating that early on in his career he associated art making with community building.3

Fig. 1. Image of Al Kotin (top left) from Harold Rosenberg’s “Tenth Street: A Geography of Modern Art,” Art News Annual, November 1958

Fig. 2. Untitled, c. 1940s. Charcoal on paper, 25 × 19 in

It was community that he would find through the classes he took at Hofmann’s small art school. Kotin was able to join the school with the help of the GI Bill after being stationed as an engineer in Virginia during the Second World War. It’s hard to overestimate the impact that Hofmann had on the painters and critics associated with the New York School. Artists who attended Hofmann’s courses included Perle Fine, Michael West, Carol

Holty, Michael Goldberg, Robert Goodnough, Lee Krasner, and Helen Frankenthaler. Even the art critic and champion of postwar American abstraction, Clement Greenberg, took Hofmann’s course.4 Many of Kotin’s paintings demonstrate the core lessons that Hofmann imparted to all his students, which were organized around formal exercises geared toward creating strong pictorial “constructions” and “dramatized space.”5 Often starting students out drawing in black and white, Hofmann had them working from still lifes with the objective of creating dynamic compositions, or “complexes,” as he called them, that aimed for ever-more sophisticated spatial relations, as opposed to naturalistic depiction.6 An undated charcoal drawing of Kotin (fig. 2) could very well have been completed during one of Hofmann’s lessons. Kotin has divided a large sheet of drawing paper into four regions, each with a small study. Hofmann encouraged such small studies, so that students could get a composition down quickly and begin to work back into it, erasing areas and darkening others, experimenting with the arrangement of overlapping planes. Drawing from direct observation, students were encouraged to think of what they saw in terms of plains of negative and positive space, a process that naturally lends itself abstraction. Kotin’s untitled drawing is exemplary of what could result from this process. While abstract, each of his four drawings is a figure study, perhaps most recognizably so in the lower right quadrant: the lighter, triangular shape on the upper right reads clearly as a bent arm, with a simplified head, depicted in profile, above it. Each panel is made up of geometrical forms of varying values, the lighter areas clearly resulting from erasing, with other areas worked back into, Kotin adding carefully placed contouring lines at some final stage in the process. Through this variance in mark-making, proportion, and value, Kotin creates multiple plains that move in and out of an illusive depth, a play with depth-of-field that Kotin successfully carried over into his brightly hued paintings. Several of Kotin’s paintings made in 1947 and 1948 demonstrate how the spatial dynamics achieved in black and white could be translated into color. In Hofmann’s classes, students moved

from value studies in drawing to color studies in paint. Students were prompted to get the same spatial nuances they achieved through value using only color. If successful, students could produce an energetic field of high-hued colors, which, in Hofmann’s oft-repeated words, “push and pull” against one another, creating a vacillating depth-of-field with little-to-no variations in value. The sense of spatial depth that Hofmann imparted to his students was always meant to be earned without violating the material flatness of the painting’s surface—one of the key formal lessons that Greenberg took from Hofmann and which we most identify with the critic today. “The essence of my school,” Hofmann said, was in “my insist[ing] all the time on depth. Suggestion of

Fig. 3. Untitled, 1947. Oil on canvas, 24 × 20 in Fig. 4. Hans Hofmann, Delight. 1947. Gesso and oil on canvas, 50 × 40 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Theodore S. Gary, 2.1956

depth. . . No perspective but plastic depth.”7 By “plastic depth,” Hofmann meant the kind of recession and projection of illusive space that comes not from the various perspectival devices used to translate three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional surface, but a depth that comes from the play of medium-specific elements off one another—color, proportion, shape, overlay. Kotin’s paintings from the late 1940s demonstrate this play in plastic form. An untitled painting from around 1947 (fig. 3), for example, is made up of deeply saturated colors, with little value added in terms of shading or contour. Through these limited means Kotin achieves “plastic depth” in his working with interpenetrating patterns of concentrated color. The large green field that sweeps through the composition is layered on top of other shapes, which sometimes carry through and over the field, ensuring that no single shape can be seen to retreat into perspectival depth and yet creating a push-and-pull effect, as various shapes project out toward and recede from the eye—spatial relations that shift depending on where your eye lands in the painting. These early paintings resemble Hofmann’s own compositions from the same period (fig. 4) and show a strong commonality in that both painters apply large areas of a single color to their compositions, hugging and covering over more intricate and graphic patterns (pl. 5). This technique of painting over in order to both knit together and complicate compositions is one that Kotin returned to throughout his career. It’s possible that it was through his time in Hofmann’s class that Kotin came to know the abstract artists associated with the downtown scene. The central place where Kotin would have familiarized himself with this group, however, was the Eighth Street Club (simply referred to as “the Club”), founded in 1948 by the expressionist sculptor Philip Pavia (its primary organizer), along with the painters Willem de Kooning, Jack Tworkov, Milton Resnick, Franz Kline, and Ad Reinhardt, among others.8 The Club was an official extension of the late-night, caffeine-fueled debates that began during World War II at the Waldorf Cafeteria, a dive of a café at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Eighth Street. Pavia lists Kotin as among its voting members in his history of the Club and includes the following note: “abstract painter, regular at the Waldorf and the Club from the beginning.”9 In Pavia’s recounting of those early years at the Waldorf and the Club, the hours sipping cheap coffee were spent quarrelling with one another over the stakes of abstraction and the American artist’s relation to the European modernists of the past. Despite the venue’s notorious infighting, most of its core participants, including Kotin, recalled the little community affectionately, expressing a deep fondness for the comradery at its heart.10

Fig. 5. Spanish Dancers, 1951. Oil and enamel on canvas, 36 × 48 in

In light of these quarrels, Pavia’s characterization of Kotin as an “abstract painter” is interesting. Among the most debated subjects at the Club in the 1950s was the definition and validity of the term “expressionism,” especially as it related to abstraction. Pavia described the core members of the Club as divided between abstractionists and expressionists, the former indicating entirely non-representational, often geometrical, painters and the latter, painters who incorporated referential content painted in a loose and energetic mode. Given Kotin’s alignment with the formal commitments he learned at Hofmann’s school, Pavia’s placing him in the abstraction camp makes sense. There is a clear emphasis on form over content in Kotin’s paintings from the early fifties, which began to incorporate graphic, Pollock-esque pours into the planar forms of his earlier works (pls. 13 and 14). While this may appear, from our currently point of view, to add an expressive element to the paintings, it’s important to remember the historically specific understanding of expressionism at this point. More than emotional content, “expressionism” indicated external reference and an extended material process. The simplicity of Kotin’s earlier paintings, along with their centering a focus on form, would seem to qualify Kotin as an abstractionist rather than an expressionist. The fact that Kotin never included overt representations of subject matter and was abstract “from the beginning,” confirms that qualification. According to Pavia’s notes, Kotin participated in one of the Club’s many invite-only panel discussions, which typically involved both artists and art critics. Kotin’s panel took place in December of 1951 and was titled “The Nature of Form.” The emphasis on form here, as opposed to content, is further evidence that Kotin was aligned with the abstract as opposed to the expressionist faction in the early days of the Club.11 In 1951 Thomas Hess, then editor of Art News, argued that despite this perceived divide a new generation of American painters, beginning with Arshile Gorky, had initiated a fusion of the two factions Pavia understood to be represented at the Club. Hess named this new style “abstract Expressionism.”12 While not the first time this phrase had been used to characterize

Fig. 6. Aaron Siskind,9th Street Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture, New York, May 21–June 10, 1951. Kotin’s Predators is pictured second from the left at the top

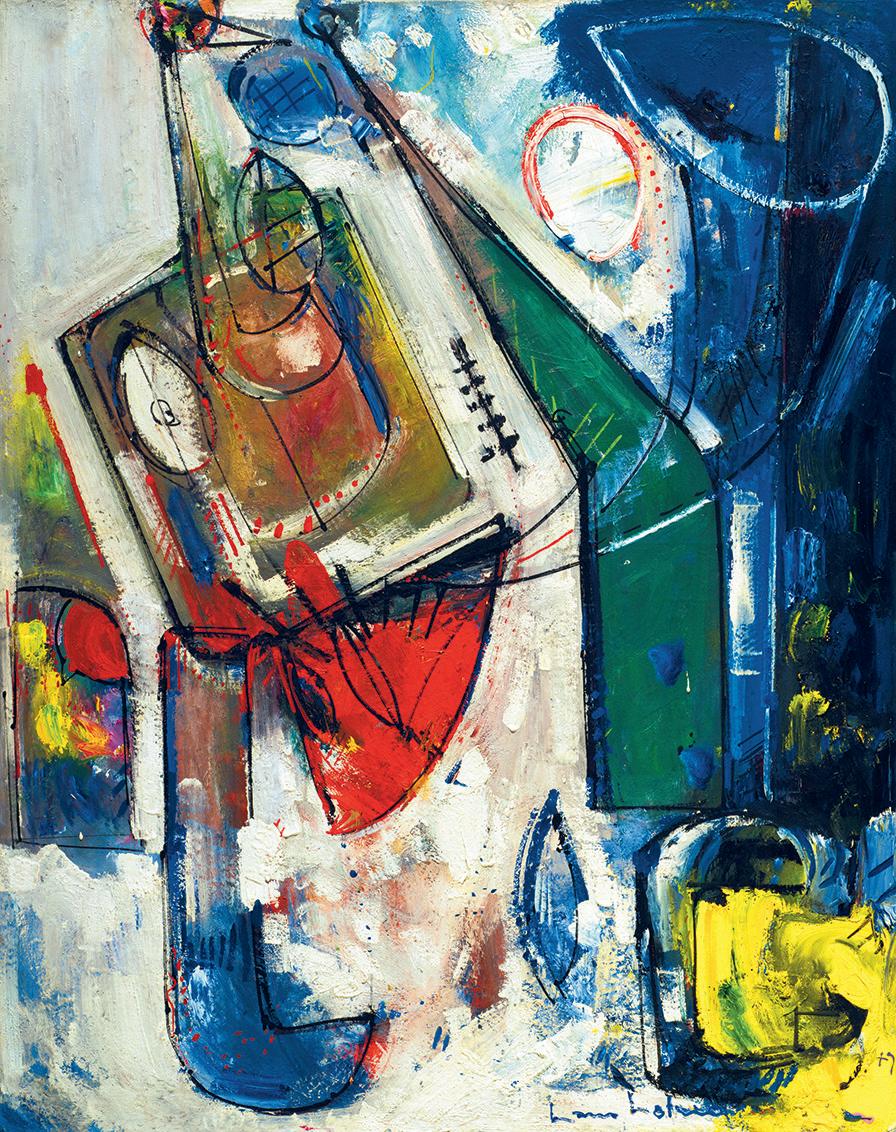

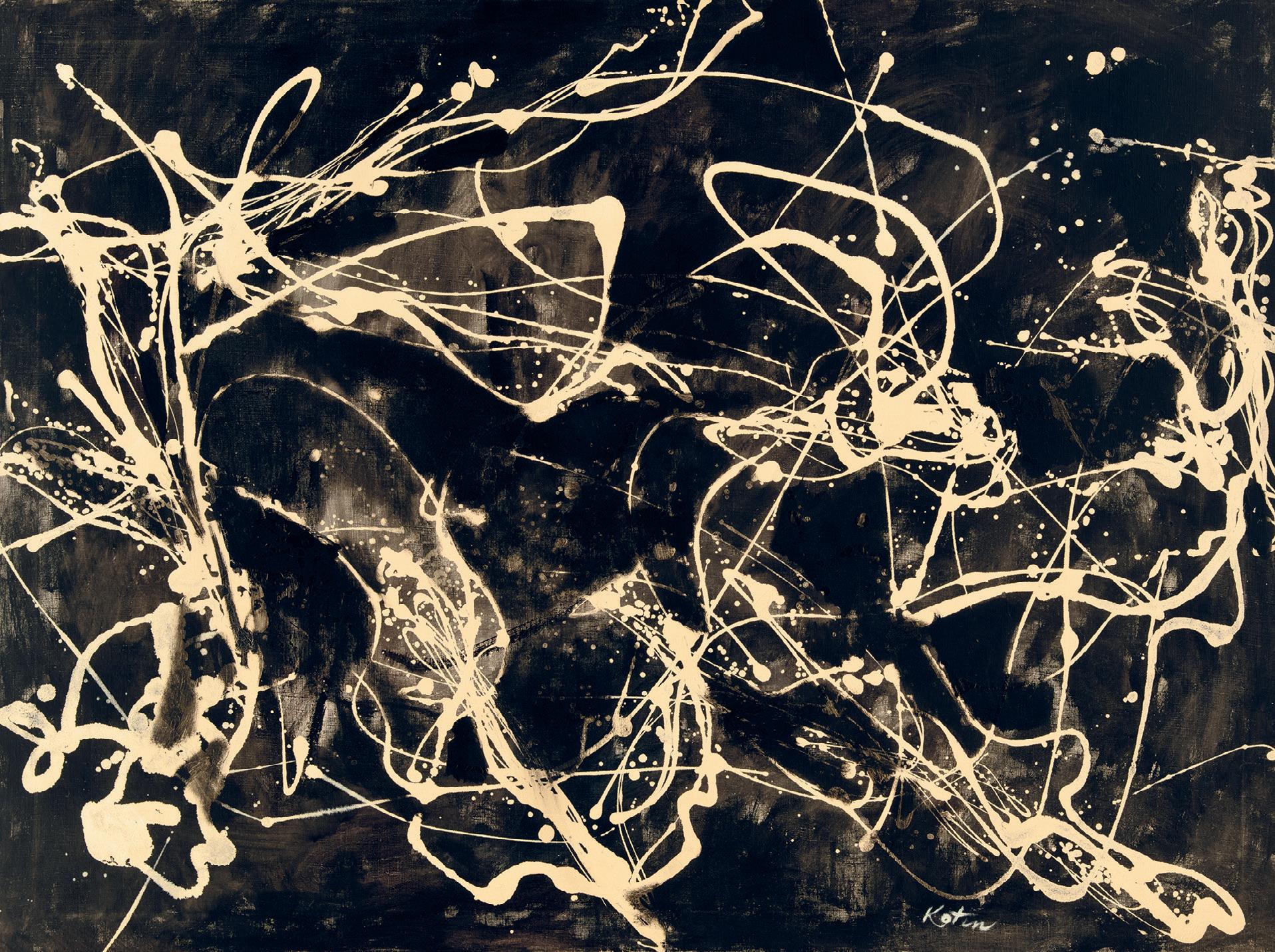

this group—Robert Coates first used it in a review of a Hans Hofmann show in 1946—it caused a great deal of controversy among the Club’s participants.13 In response, Pavia called for a public forum to assess what he described as the “Hess problem.”14 What emerged was a self-conscious relation to both expressionism and abstraction among many of the artists associated with the Club—a self-consciousness that is exemplified in the paintings Kotin began to make in the mid-1950s. In the early 1950s Kotin was making paintings that incorporated a Pollock-like pouring technique, which introduced a graphic and gestural element, as seen in works such as Spanish Dancers and Predators (fig. 5 and pl. 18), both from 1951. Predators, which combines web-like pours with the plains of color that he played with in earlier works, was included in the groundbreaking Ninth Street Show of 1951, an exhibition of sixty-one artists organized by members of the Club and hung by the gallerist Leo Castelli (fig. 6). The show was put together in the hopes of garnering some attention to the wider field of New York School artists, given the limited interest in the group at that moment by both commercial galleries and the press. The result was hugely successful, with crowds gathering in lines down the block the night of the opening. Given this initial success, the tradition was continued for five years at the Stable Gallery in Uptown Manhattan—yearly exhibitions that came to be called the Stable Annuals. All the exhibitions were organized by a panel of artists that chose the works to be included, a process of selection that earned the Annuals a great deal of respect. Kotin was one of the few artists to be invited to participate in every Annual, an honor for any artist, given the prestige the exhibitions garnered.15

Fig. 7. Grace Hartigan, Aristodimos Kaldis, George Spaventa, Al Kotin in booth, at Cedar Tavern. 1959, printed 2017. Gelatin silver print. Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund (2017-36)

A few months following the Ninth Street Show, Kotin had his first solo exhibition at the Hacker

gallery, which also featured his more gestural paintings. This solo-show, along with the five Stable Annuals that followed the Ninth Street Show, would be the only exhibitions Kotin had until 1958, when he had his second solo exhibition, this time at the Grand Central Modern Gallery. In those intervening years Kotin began to produce paintings that seem to have been made with an acute awareness of the newly forged intersection between abstraction and expressionism: medium-to-large-scale paintings with churning swaths of thickly applied paint evenly distributed across the picture plain. Kotin’s 1953 Calliope I (fig. 8) and 1954 Downbeat (pl. 20) are exemplary of this moment in his career. In these paintings Kotin moved away from thin washes of color, as well as from poured paint. Instead, a thickly impastoed paint covers the entire canvas, edge-toedge, creating an all-over, tactile surface. The artist’s hand is clearly visible as a heavily loaded brush is used to make scoring-like marks which add a directionality to the painting, not unlike a windblown landscape. A reviewer of the Grand Central Modern show offered a compelling description of these more elemental and robustly painted works: “A conflagration, a tidal wave, a typhoon— these are some of the drastic upheavals suggested by Kotin’s turbulent rivers of paint as they clash or melt with each other.”16

Landscape and weather systems are more than appropriate metaphors for Kotin’s paintings. A prolific writer of poems and descriptive prose, nature is a reference Kotin returns to in his writing with some frequency. The centrality of natural forces to his creative process is made clear in a statement Kotin published in the 1959 issue of It Is: A Magazine for Abstract Art (Pavia’s journal, which mainly published writings by artists and critics associated with the Club, including the occasional transcript of discussions and debates). Kotin writes:

Space, interwoven within itself, a curtailed infinity moving with a force that creates an element of time and emotion, slapping against its enclosing surface with the sound of waves breaking out but returning with a rush to embroil itself once more within the canvas, losing itself in a confining density of green, and groping its way from this jungle into an even denser wilderness of white, or red, or yellow, exposing the elemental forces of a world with its surface removed like a concrete orange peeled with clawing fingers, seeking for release yet never daring complete freedom, for that would be the end.17

Fig. 8. Calliope I, 1953. Oil on canvas, 36 × 30 in

Reproduced in black and white, along with this statement, is a painting that follows the same principles as Calliope I and Downbeat. Even in black and white, it’s clear this is a thickly painted work, which achieves the same kind of directionality through scoring and paint application as the two earlier works. Kotin’s description in his statement of space and movement is clearly taken up in such paintings. One thinks of roiling water or high grasses bending with the wind. Through texture alone, Kotin was able to capture the force of natural processes in a manner that is redolent of J. M. W. Turner’s tumultuous nineteenth-century seascapes. Despite the extraordinary materiality of Kotin’s paintings in this period, there remains the traces of the planar pushing and pulling that he mastered following Hans Hofmann. An unresolved tension arises between the extension and lightness of color and the weight of the material and haptic surface—a tension that Kotin captures in his 1959 statement with phrases such as “curtailed infinity” and “concrete orange.” In Calliope I that tension is evident in its clockwise movement, which creates a pull toward the center and begins to intimate a depth of field. The swirling robes that Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry, is often depicted as wearing come to mind, as the heavy paint sweeps upward with a light and lyrical motion. An untitled work from 1954 (pl. 26) shows how color enunciates this tension. Here heavily applied, densely hued areas of paint are combined with thin washes of color that glide over that more turbulent, “concrete” surface (which can be seen in the lighter, sky-blue areas of this painting). The elemental coming together of such disparate formal attributes is evident in Kotin’s paintings well into the 1960s and is reinforced in his titles of the time, such as Tidal, Submerged, and Westerly. Toward the end of the 1950s, Kotin began to expand his visual vocabulary in two directions. First was a return to his interest in the planar play between color and form that was present in his paintings from the late 1940s and early 1950s. In an untitled painting from c. 1958 (pl. 30), as well as paintings such as Imperturbable (pl. 41) and Azimuth (pl. 42), both from 1961, the heavily textured surface calms down and is replaced by a softer touch and a more calming energy. As the name Azimuth (a term that can be used

to designate the position of a celestial body in relation to an observer) begins to indicate, these paintings seem to move away from the earth-bound turmoil of the earlier works, and

to look instead toward the celestial canopy. Both of the 1961 paintings are made up of long strokes of the brush, covering the surface with gestural marks, but leaving behind the impasto of the earlier works. There’s an impressionistic element to these works, with the 1958 untitled piece and Imperturbable recalling Claude Monet’s waterlilies. The abiding concern in each seems to be color and how color relates to the picture plain—a key formal element that art historians identify with Monet’s later works, which depict the water’s surface. Again Kotin makes clear his

Fig. 9. Night Ride, c. 1960. Oil on canvas, 24 × 40 in

ability to indicate a kind of depth of field without using perspectival devices. This comes from the overlapping of color, as seen in lower right-hand corner of Azimuth, where crosshatched areas of yellow and orange overlap with a similar shape painted in black. Kotin often used a brightly hued under painting during this period, which you can see in the occasional orange areas in Imperturbable, which intimate a brighter plane beyond the darker surface of this blue and green all-over field. A similar play with color and form can be found in Night Ride (fig. 9), painted in early 1960, which moves even more assuredly away from texture and materiality and toward optical play. Here the surface is even smoother and the colored forms more clearly delineated from the back ground, the floating blue forms on the left and the orange, rectangular form of the right demonstrating the push-pull effect that one can achieve through formal variant. Night Ride is also an example of the second direction Kotin moved toward beginning in the early 1960s: an exploration into the size and placement of the material canvas. Night Ride, along with several other works from this period (pls. 39 and 43), is a diptych. Two separate canvases, painted independently of each other, are mounted together into a single picture. The differences between the two panels is emphasized. In Night Ride, for example, the right side of the left canvas comes to an end with a light, blue-hued shape running over the edge of the canvas. This cropped form is met with a large, dark rectangle on the right canvas, which contrasts with the left in value, shape, and placement. The difference between the two canvases is further emphasized in an untitled painting from the same year (pl. 43), the right panel, painted mainly in greens is joined to a panel painted in warm hues, the separateness of the contrasting palettes emphasized in their coming together. Kotin’s extension of formal experimentation to the material substrate of the canvas is also seen in his play with scale. Sometime in the late 1950s, Kotin began to make miniature paintings, at their smallest, three-by-five inches, and increasing to around six-by-twelve inches (pls. 47 and 48). These little paintings are quick and expressionistic. For all their quickened energy, however,

Fig. 10. Untitled #13, c. 1964. Oil on canvas mounted on board, 4 7/8 × 5 3/4 in

they still demand a serious response from the viewer in Kotin’s careful craftmanship—the same play with form, color, and texture is very much on display, as is his interest in the diptych format (fig. 10). The little expressionistic paintings seem to comment on Abstract Expressionism’s increasing institutionalization. By the late fifties, Abstract Expressionism, the “unwanted title,” as Pavia called it, had won out as the official name of a generation of American artists. A narrow mode of expressionism, dominated by dramatic gesture on a large scale, had become ubiquitous, dominating the galleries in both Downtown and Uptown Manhattan. Thomas Hess, who once celebrated expressionism’s material innovations, bemoaned the nearly uniform adoption of this large-scale, “gestural” style by the late 1950s. Reviewing three large, highly regarded exhibitions in the winter of 1959, Hess was disturbed not only by the ubiquity of Abstract Expressionism, which was abundantly illustrated in Hess’s article by image after image of “expressionistic” paintings from nearly every continent. He was also troubled by the seemingly insincere reduction of expressionism to the drama of the gesture, which he described as appearing in these paintings as a “slash of a gesture that must have jerked a painter around like an acrobat moves through these neo-stratospheres like toy spark.”18 By 1960 Abstract Expressionism had also come to be associated with a kind of American heroism, as demonstrated by the Museum of Modern Art’s 1958 exhibition The New American Painting, which was involved in a sprawling web of Cold War commitments.19 The exhibition traveled to eight European countries and helped to establish Abstract Expressionism as an emblem of the “triumph of American painting,” as Irving Sandler put it in 1970.20 Kotin’s diminutive paintings might be read as a reaction against this overblown nationalistic rhetoric. A long-time pacifist and one of the very few Abstract Expressionists to have served in the Second World War, Kotin was increasingly opposed to the politics that dominated the latter half of the twentieth century, marked by a recursive call to arms.21 This and later shifts in style demonstrate Kotin’s abiding commitment to experimentation in both form and content and his on-going responsiveness to the cultural and political climate of the day. While many painters of his generation continued to make paintings that repeated the

expressionistic style that they had first landed upon in the late 1940s for the rest of their careers, Kotin’s style continued to develop and shift with the world around him. From the diptychs and miniaturized paintings, to his later inclusion of text in his paintings—demonstrating his interest in the intermedial experimentations of the late 1960s—and his pictures of tortured faces in close up (pl. 65), which culminated in his 1974 installation Testigos (Witnesses) in Mexico City—a large number of smallish paintings of distraught faces that were installed on the floor in a constellation meant to confront a mobile viewer—Kotin never settled into any one style. For all that, his story remains central to the history of American Abstract Expressionist painting. As a reporter writing for the New York Herald Tribune in 1964 wrote, “Albert Kotin comes out of the magic circle that produced Gorky, Pollock, de Kooning, and Kline, when the work of those more celebrated painters made their strongest impact.”22 His paintings continued to bear the mark of that circle throughout his career, for Kotin never left behind the commitments of the little “artist colony” that first took seed on East Tenth Street in Lower Manhattan. His multiple experiments in material and style, sustained for the duration of his career, make clear his central place in the history of the New York School of painting.

Christa Noel Robbins is an associate professor of art history at the University of Virginia. Her recently published book, Artist as Author: Action and Intent in Late-Modernist American Painting (University of Chicago Press), provides the first extended study of authorship in midtwentieth century abstract painting in the United States. Her essays and reviews have been published in a variety of outlets, including Art in America, Oxford Art Journal, Art History, and Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts, and she was the advisory editor of North American modernism for the Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism.

Notes

1. Harold Rosenberg, “Tenth Street: A Geography of

Modern Art,” Art News Annual XXVIII 57, no. 7 (November 1959): 184.

2. Rosenberg, “Tenth Street,” 137. 3. Quoted in Gerald E. Markowitz’s essay for Albert

Kotin: 1907–1980, Memorial Exhibition, n.p.

See also “Albert Kotin: American Abstract

Expressionist Artist of the 9th Street Show,” narrated by Phyllis Braff, 2009.

4. See William C. Seitz, Hans Hofmann: With Selected

Writings by the Artist (New York: Museum of

Modern Art, 1963).

5. The quotes are from Nell Blaine and Al Held, respectively, both of whom were students of

Hofmann’s. See “The Reminiscences of Nell Blaine:

Oral History, 1979,” Oral History Archives at the

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia

University (28) and Al Held, “Oral history interview with Al Held,” November 19, 1975–January 8, 1976.

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

6. Irving Sandler, “Hans Hofmann: The Pedagogical

Master,” Art in America (May 1973). 7. Hans Hofmann, quoted in Sandler, “Hans

Hofmann,” and Frederick S. Wight, Hans Hofmann (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

Press, 1957), 24.

8. Philip Pavia, Club without Walls: Selections from the Journals of Philip Pavia, edited by Natalie Edgar (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2007), 3–67.

9. Pavia, Club without Walls, 3–67. Pavia had multiple levels of membership, with charter and then voting members being the highest. 10. See Markowitz, n.p. 11. The Club records kept by Philip Pavia, 1948–1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian

Institution. 12. See Thomas Hess, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase (New York: Viking Press, 1951). 13. Among the first descriptions of New York School painters as “abstract Expressionist” came from a review of a Hans Hofmann show by Robert

Coates: “Art Galleries: Abroad and at Home,”

New Yorker (March 30, 1946): 83–84.

14. For an account of the debates, see Philip Pavia,

“The Unwanted Title: Abstract Expressionism in Two Parts. Part I The ‘Hess-Problem’ and

Its Seven Panels at the Club, 1952,” in It Is:

A Magazine for Abstract Art 4 (1960). 15. See Marika Herskovic, ed., New York School,

Abstract Expressionists: Artists Choice by Artists (New Jersey: New York School Press, 2000). 16. “Albert Kotin,” Arts Magazine 32 (May 1958): 57.

17. Albert Kotin, “Statement,” It Is: A Magazine for