10 minute read

Nu‘u: In the Nineteenth & Twentieth Centuries

By Andrew Walmisley (Part 2)

When Elia Helekūnihi was born on April 12, 1839, at Kuakini, Nuʻu, the ancient district was still a relatively thriving, well-populated community. Though much depleted by western diseases, warfare, and out-migration to the port towns favored by haole traders, missionaries, and the Hawaiian chiefs, it was not yet the “marginal” district it was to become later in the century. There were many reminders of the great days of the early 18th century when Aliʻi Nui Kekaulike made his royal center at Mokulau and Nuʻu and the district boasted as many as 20,000 inhabitants.

Advertisement

The forested upper slopes of Haleakalā received greater rainfall and the landscape was more verdant, with greater surface flows in streams and springs than we see today. The famed ‘uala gardens still flourished even in the drier portions of Nuʻu, pili grass used for thatching houses dominated the grasslands, and dryland kalo was still cultivated in the rainier uplands.

Nuʻu school and Protestant meeting house across the government road from the fishpond was an important community center. Dating from at least 1827, it was founded by the local konohiki under the direction of Queen Ka'ahumanu, and there is a record of Princess Nahienaena (age 13!) examining the school and preaching sternly to the makaʻāinana in 1828. On the wall of petroglyphs not far away, neatly engraved letters can be seen: testimony to the pride Hawaiians had in learning the palapala. Elia attended the school from 18451847 under the guidance of his uncle Solomona Aki. The school had 110 students, suggesting that Nu’u may have had as many as 500 inhabitants at this time! There was also a sister school at Waiū, which remained a thriving community up to the end of the 19th century.

Nu'u Salt Pond

Aldei Kawika Gregoire

Though Nuʻu was largely converted to the Protestant faith through the efforts of local konohiki, such as Elia’s father Paulo Kū, by the 1840’s many people in Kaupō had converted to Catholicism, possibly as an act of resistance to the rising tide of Protestant American influence. A makaʻāinana of Kahikinui, Helio Koaeloa, spread the Catholic faith in East Maui and built small chapels at least four years before the arrival of the first French Catholic missionaries. It is likely that he built the small Catholic chapel, whose ruins can be seen on a rise mauka of the highway a few hundred yards towards Kahikinui. When the French priest, Modest Favens, arrived in 1846, he found hundreds of newly-converted Catholics eager to be baptized, all of whom had come to the faith through Native Hawaiian agency without the assistance of a priest. Several Catholic schools were established, one possibly on this site, as well as two other churches— one upcountry at Maua and the other where St. Joseph’s stands today.

Another threat to the Protestant establishment at Nuʻu was the arrival of the first Mormons in the early months of 1852. Elder James Keeler arrived in the community “after a hard day’s travel” by canoe and over rough lava “very sharp to the feet.” He stayed in the house of “one Manu who is very friendly” and talked with the people of Nuʻu “considerable (sic) on the first principals (sic) of the gospel.” A year later, George Cannon visited the Mormon chapel at Nuʻu and stayed with Manu near the spring at Waiū. Cannon “gave them a history of the restoration of the church to the earth in these last days through the ministry of angels to Bro. Joseph Smith, & c., in which they seem very much interested.” It seems that the population was large enough to sustain two Mormon chapels at both Nuʻu and Waiū. This is not surprising because as late as the 1890’s, Josephine Marciel claimed that 100 people still lived at Waiū!

During the devastating smallpox epidemic of 1853, Canadian economist, John Rae, passed through to vaccinate the people of Nuʻu and kept a diary describing life in the district at the time. He wrote that he stayed with Paulo Kū near the sea at Nuʻu “where dashing lulled me to sleep.” The house was small, but comfortable with “plenty of mats.” Later, he counted a thickness of 12 lauhala mats on the floor of the hale! He describes Nuʻu as “a little hamlet of some dozen houses, some with stone walls." He ate “foul poi” made from ʻuala and in the morning was given ʻopihi to eat. Sadly, he reported that there were “some old women terribly marked with the venereal.”

Rae fell ill and Kū’s wife, Lydia Kalaoa, kindly offered him hospitality and when he offered the family money for their efforts, Kū said that “it would not be right to make a charge as I was helping them.” He continues, “The people are very pleasant and kind, working at something or other all day. Making nets, the men; the women making kapas for the native blanket.” He writes about cultivation in the “very stony soil,” but “when the surface stones are thrown into the form of low rude fences, the intervening spaces cultivated in the native manner yield largely the sweet potato and the onion, with here and there a few heads of tolerable maize.” Rae took a walk “with the youth,” likely Kūʻs son, Elia, for about two miles mauka in Nuʻu and found about 3/5 of the surface of the land planted in ʻuala in “holes from which the stones were gathered by hand.” He also noted that melons and “the native calabash” thrived in Nuʻu mauka. Paulo Kū took him for a walk to the “puna wai” (spring) at Waiū “where they get their best water for drinking. It is a great stream issuing from the bluff to the N.E. and about a mile distant...It never fails and is very pure and cool and is quite a treasure. It is fenced with care by stone walls and a good road is made to it.” The spring at Waiū, according to other contemporary accounts, had considerable flow well into the 1890’s. The roads described by Rae can still be seen: a well-preserved section of the 16th century Piʻilani trail, as well as an excellent stretch of Governor Hoapili’s 1830 “road that sin built” can be seen running across the lava flow from Nuʻu landing to Waiū. The Hoapili road can be seen continuing up the gulch behind the spring to join the main road on the crest of Puʻumaneʻoneʻo and according to one old map, it also branched to run along the cliff to Kou, connecting the two communities.

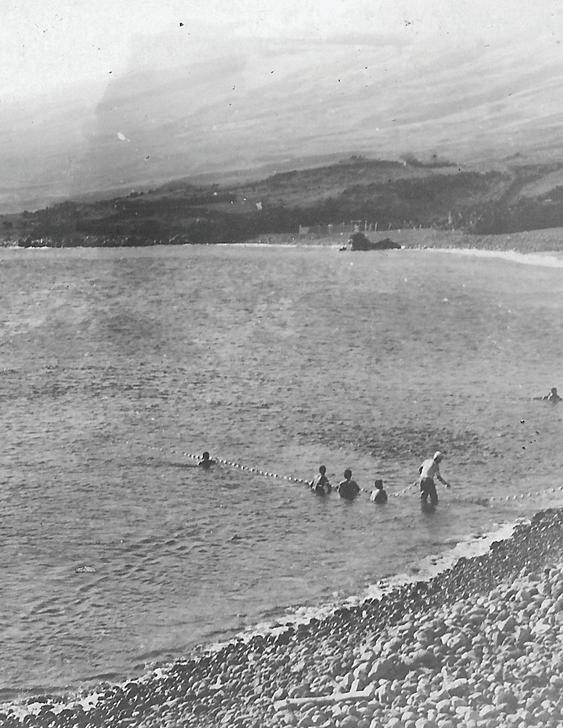

Nu'u Akule Fishing

From the Personal Collection of Mina Atai

Major change arrived in Nu’u with the construction of the landing in the late 1850’s. Petitions from the local people in 1856 complained about the difficulty of getting products to market, and by 1858, the landing was in place and Judge John Richardson celebrated the profitability of shipping goods to market in Lāhainā and Honolulu from Nuʻu. In 1862, Nuʻu had become an important landing for both passengers and products, such as pigs, goatskins and dried fish, and later in the century, when ranching began to dominate the local economy, cattle were swum out to the waiting steamboat by paniolo on horseback from the Kahikinui end of the beach, where the old corral can still be seen. The rapidly declining population of Nuʻu, formerly concentrated mauka from the petroglyphs to Hawelewele Gulch (wisely, to avoid tsunamis!), shifted to the area back of the landing, where a cluster of American style houses, a small general store, and a hale paʻakai (salt house) stood until the early 20th century.

Educated at the boarding school in Hāna and at Lāhaināluna, Elia Helekūni returned to teach at Nu’u in 1859 after the retirement of his uncle. He was alarmed to find that the school population had dropped to 49 children (it was 110 in 1841), demonstrating the rapid demographic decline of the district.

In 1861, he wrote of a contagion at Nuʻu, which he called “an illness with red protuberances or bumps,” possibly a re-infection of the smallpox epidemic of 1853. “It started at the school in the last week of October and intensified in the first week of November,” he wrote, “affecting above all the little children.” Most of the children in his school were “completely exhausted” by this illness, which is “truly devastating.” One little girl from his school, named Kahi, died.

Shortly after he wrote this letter, painful memories of the passing of his own beloved Solomona the year before inspired him to write at Nuʻu in 1861 a beautiful kanikau:

In the evening your passing was like the setting of the sun. Yours is the spirit that departs in the evening, With the billowy clouds of Haleakalā, We two shall be in the cold and chill, In the long night of winter, sleeping...

The grief of the Nuʻu makaʻāinana at the loss of so many dear ones is poignantly demonstrated by the abundance of burials in the area. By 1880 the school had closed and a Board of Health official requested its use as a “holding facility” for lepers waiting to be sent to Kalaupapa.

In the 1870’s Nuʻu passed to King Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani. After the King’s passing, the Queen sold the western portion to James Campbell, who was, incoincidentally, related by marriage to the King and Queen. The great wall that forms the eastern boundary of Nuʻu was constructed by the Queen in 1896 to establish clear boundaries at the time of the transfer to Campbell. A small community, residing mostly close to the fishpond, farmed and fished at Nuʻu well into the early 20th century and was described by Thomas Maunupau in his famous visit in 1922. It is believed that the devastating tsunami of 1946 finally put an end to the life of this “village.”

Nu'u Bay

Dawn Jermaill

The National Park acquired the Campbell portion in recent years, and the eastern half, purchased in 1906 from the Kapiʻolani estate by Antone Marciel of Maua Ranch (later Kaupō Ranch), is now divided between Nuʻu Mauka Ranch and HILT, with the makai lands constituting the HILT reserve.

The doctoral work of Andrew Walmisley explored nineteenth century Maui colonial history through the lens of the life of one Hawaiian man, Elia Helekūnihi (1839-1896), who was born at Nuʻu, Kaupō, into a lesser aliʻi family in the lineage of King Kekaulike. Helekūnihi was a key player in the major events that defined his people as they struggled to find their way through the painful challenges of that century: depopulation, disease, and loss of sovereignty. Andrew Walmisley received his doctorate in Hawaiian History from the University of Birmingham in the U.K. He is currently doing research for a