33 minute read

Covid adds to SAT anxiety

Testing Colleges’ LIMITS

BY DAMALI RAMIREZ

Advertisement

Elmont High School junior Noor Shahin believes taking the SAT will increase her chances of getting into any Ivy League school like Columbia. Photo provided by Alexandra Martinez. Hearts are beating, legs shaking, sweat dripping. It seems impossible to concentrate. In 180 minutes, students must demonstrate their college readiness by completing the math, evidence-based reading and writing sections of the Scholastic Aptitude Test. Before Covid-19, students’ eyes would wander around the room trying to outscore their peers in the hope of getting into their dream colleges. Now, students sit in socially distant classrooms, wondering if someone around them has Covid-19. the limited testing opportunities, and about 1,700 schools did not require SAT or ACT scores for this year’s applicants. Yet, many Long Island high school juniors and seniors are opting to take the exam, despite the obstacles they face, like testing sites closing, filling up or being too far. The College Board website advises students to be vigilant the night before and morning of exam dates about test centers closing or making short-notice changes. “I think it’s definitely become normalized, and I feel that [students] just want to show that they do know some of the material,” said Nina Rashid, a Syosset High School junior. Last summer, Nina couldn’t take the SAT because testing sites were closed or too far. Although there is still uncertainty about testing sites closing, she registered for the May and June test dates at her school. She, like other students, said she believes universities prefer high SAT scores over high grade point averages. Elmont High School junior Noor Shahin decided to take the exam in the hope of getting into an Ivy League school like Columbia.

From a young age, she said, she was told she had to take a college entrance exam and thought it was a test she couldn’t skip, even though Columbia announced it would not require next year’s applicants to submit their scores. To her, she still believes colleges consider SAT scores important. Last year, Shahin emigrated from Egypt to the United States and felt clueless about the SAT process. She hopped on the College Board’s website to download practice exams, used Khan Academy and signed up for a SAT prep course that her school offered juniors this year.

Unlike Noor and Pelumi, Abena doesn’t take hybrid classes and worries about returning the school building for her exam. Photo provided by Alexandra Martinez.

Despite all her preparations and hybrid-learning, she does not feel confident and is struggling to pay attention in her online classes, saying she has lost her motivation to study. “I can’t even concentrate in class. The days I’m online, I don’t care about class. I’ll open it and then watch Netflix, and every student does that,” she said.

In December, she tried to register for the exam, but the list was too long, and the closest test site was 30 minutes away in upstate New York.

“I can’t drive 30 minutes away to a school I don’t know to take an exam,” Shahin said. She tried to register again in March, but her test date was canceled because of the virus. Her guidance counselor then informed her that the school was offering a test date in April. Despite the obstacles, she knows she can retake the test and only has to worry about testing sites closing. “I’m still a junior,” Shahin said, “and I feel sorry for the seniors whose exam got canceled, couldn’t take it, and now they have to do it this year while preparing their college applications.” Like Shahin, Pelumi Ukinamemen, an Elmont junior, was also taking the exam on April 13. She heavily relied on Khan Academy to study for the SAT and focus on areas that she needs more practice in. The schools that she is applying to in Texas require SAT scores, but she is also taking the test as a precaution. Even if the scores are made optional, Ukinamemen plans to submit her scores to demonstrate all the hard work that she has completed. “We have the SAT, some of us have [Advanced Placement] exams and the Regents coming up. All of that together is in two months, and we’re all racing to study all of this stuff. It’s really stressful,” she said. Unlike Shahin and Ukinamemen, Elmont junior Abena Opoku-Mensah takes all her classes online and worries about returning to the school building. “Last year, we had to take the [Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test] in October, and I remember that the day after we went in, they closed the school because there was a positive case,” she said. “It felt so weird because I stayed home for so long, and the day I go back is the day there’s a positive case in the same building at the same time as me.” Opoku-Mensah said she tries to study an hour every day and is in a study group that meets from 7 to 9 p.m. She also juggles AP and Regents exams and plans to apply to Ivy League schools. “I don’t care about my score, since a lot of schools are saying that it doesn’t matter, but it’s still also really important to me, so I’m kind of conflicted about it,” she said.

Forty students from Elmont Memorial Junior-Senior High School, Valley Stream South High School, Westbury High School, Syosset High School, East Meadow High School, West Hempstead High School and Farmingdale High School recently took part in a survey conducted by Pulse involving their experiences with the SAT.

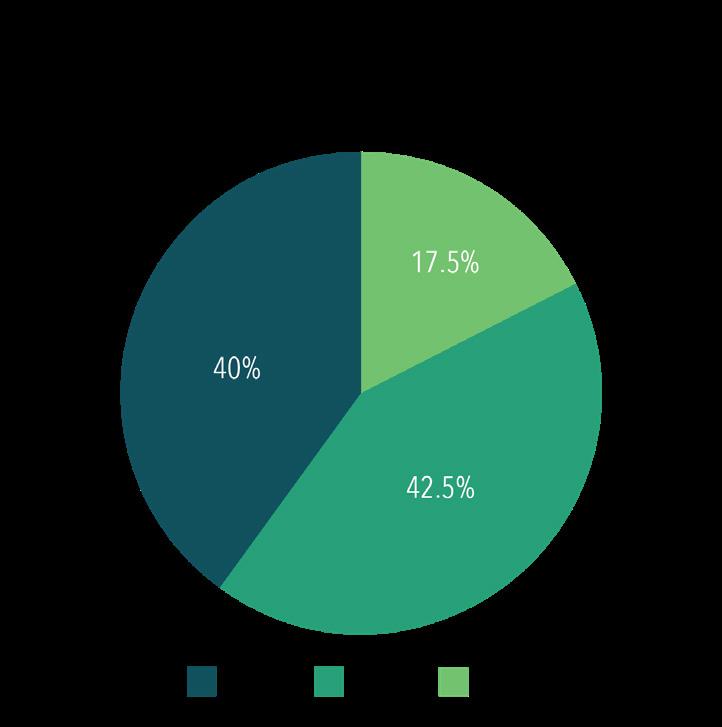

In the survey, 60 percent of students said they had already taken the SAT, 17.5 percent said they were scheduled to take the exam, and 22.5 percent said they did not plan to take it. Overall, 42.5 percent of participants said they experienced difficulties scheduling test dates.

A PANDEMIC OF HEALTH INEQUITY

BY REBECCA CANFIELD

Since the first confirmed coronavirus case was reported in Nassau County in March 2020, Long Island has been a hotspot of Covid-19 infection, with case numbers erupting last spring not only in Nassau but also Suffolk County, before stabilizing last summer and then soaring again over the winter.

Systemic healthcare inequities have put people of color at a higher risk of contracting Covid-19, being exposed to the virus and dying from it, according to government officials. A number of policymakers, like Nassau County Executive Laura Curran, have worked to combat the long-standing inequities that have led to disparate health outcomes in communities of color.

“Health equity has been a cornerstone of our response strategy …. We were one of the first counties hit, so the trends that we’re all seeing nationwide, we saw them first,” said Jordan Carmon, a senior adviser to Curran.

Covid-19, in many ways, exposed the nation’s healthcare inequities, which the

World Health Organization defines as “avoidable, unfair or remediable” differences in the quality of treatment.

COVID-19 HEALTH DISPARITIES

In New York State, the Covid-19 death rate among white people is 66.6 in 100,000, while it is 169.8 and 147 in 100,000 for Black and Hispanic New Yorkers, respectively. In Nassau, the mortality rate for Black people — at 228 in 100,000 — is roughly 25 percent higher than the rest of the state, and the rate among Hispanic people, at 154.4 per 100,000, is slightly above the statewide average. In Suffolk, the rate for Black people — at 237.8 per 100,000 — is 29 percent higher than the statewide average, and for Hispanic people, it’s slightly under the statewide average, at 144.1 per 100,000 people. Health disparities can be found not only within Covid-19 trends, but also for almost any health condition.“You can slice and dice data based on really any demographic — race, ethnicity, age, gender identity, zip code — and find inequities,”said Dr. Anthony Santella, an associate professor of health professions at Hofstra University. Even before Covid-19 hit, many Long Islanders faced basic unmet needs, which were only made worse by the pandemic. “Healthcare access is necessary, but not sufficient in explaining the differences or these inequities in the health outcomes,” said Dr. Martine Hackett, associate professor of health professions at Hofstra. “What we saw with Covid-19 was that the environmental conditions contribute to the differences in cases. Stressors take a toll on our body as well.” Factors that contribute to the increased risk that communities of color face include a lack of healthcare access, poverty, housing or homelessness, occupation and discrimination. “Health equity is about ensuring that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to achieve their full health potential, and you don’t have to be a scientist or a doctor or a health professional to know that doesn’t exist in the United States,” Santella said.

“Minority groups are more likely to have some of the burdens that put people at higher risk for Covid,” Santella said. People in communities of color, he noted, are likely to be essential workers, use public transportation, live in densely populated homes and live in poverty, he said.

POLICIES IN PLACE

The pandemic has also changed the way that communities and policymakers connect and support one another, with healthcare policy becoming interlaced with public policy. Nassau and Suffolk counties have made a number of changes in order to provide quality healthcare to those in need. Hackett, drawing on her former work as deputy director at the New York City Department of Health, identified the risk factors for communities of color. “The first step,” she said, “is acknowledging and understanding there is a problem in order to pull out those key underlying factors, like racism.” In November 2019, Nassau County introduced its first director of health equity, Andrea Ault-Brutus. She was brought in to examine the general health disparities that exist in both Nassau and Suffolk counties. According to Carmon, Ault-Brutus has made enormous changes in the county, beginning with the approach to public information. She has initiated awareness campaigns that encourage people to seek medical care and know the signs. Long Island needs “a holistic approach, not just for Covid,” Ault-Brutus said, and health-equity campaigns should go through “trusted community partners, like houses of worship, community groups, and nonprofits that have regular contact with the people in these affected areas.” This trusted messenger strategy, in particular, helps county officials to promote the safety and efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccines to a suspecting public. Beyond Ault-Brutus’ position, Carmon pointed out the county’s financial commitment. “Money is continuing to go towards health centers within these hotspot communities to allow for free testing and resources to those who don’t have insurance, access to affordable care or are undocumented,” he said. The county “has and will continue to help reduce those disparities we see geographically.”

As part of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s mandate to ensure equity in the vaccination distribution process, the New York State Department of Health and Northwell Health recently worked with churches in underserved communities to deliver Covid-19 vaccines to locals. Photo courtesy of Northwell Health.

THE PROBLEM?

VACCINE INEQUALITY

Photo provided by Mat Napo - Unsplash

BY DAMALI RAMIREZ

Scrolling through Walgreens’ Covid-19 vaccination home page recently, 71-yearold Rase Denny, a retired nurse who worked for more than 30 years at Winthrop-Univeristy Hospital in Mineola, had no luck finding an appointment near his Uniondale home. After weeks of having his name down on the waitlist and searching at different locations, Denny received a phone call about an available appointment. “Walgreens didn’t have anything, and then I got a call that somebody didn’t show up, and at that point, I was able to automatically book my second appointment 30 days after,” he said.

Denny was among the 43,800 Black residents on Long Island—out of a total population of more than 250,000—who had, at press time, received at least one dose of the vaccine, and then he faced challenges securing an appointment for his sister. Across the nation, the vaccination rate among communities of color has been significantly lower than in white communities, despite the higher Covid-19 infection rates in such areas.

On Long Island, of the nearly 811,000 people who have recieved at least one dose of the vaccine to date, 84.6 percent have been white, including Hispanic people; 8.6, Asian; 5.9 percent, Black; and .9, other according to New York State Department of Health data by race. The Census Bureau definition of white includes anyone of European, North African or Middle Eastern descent.

The state further parses out data by ethnicity. According to this data set, 9.6 percent of Hispanic or Latinx people on Long Island have received at least one dose of the vaccine.

White people—not Hispanic or Latinx— comprise about 63 percent of Long Island’s total population, but to date, they had received 75 percent of Covid-19 vaccine doses. Meanwhile, the percentage of Black people recieving one dose was roughly 5 points lower than their percentage of the population, and for Hispanic people, it was more than 7 points lower. That is, non-Hispanic white people were overrepresented among those receiving their first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine, and Black and Hispanic people were underrepresented, while Asians were slightly overrepresented. Dr. Jeffrey Reynolds, chief executive officer of the Garden City-based Family and Children’s Association, said he was not surprised when the data showed lower vaccination rates among Black and Hispanic communities, noting past health care disparities between white communities and communities of color.

“I think what Covid initially did was it exposed all the fault lines that have been around since the beginning of time and made them clearer,” he said. “There’s a number of reasons particular to Covid. The disparities were there, but some of them relate to the prevalence of pre-existing conditions, and some of them relate to essential workers and the jobs they’re doing.” According to the Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research institute, Long Island has about 311,000 essential workers; 11 percent of them support their families on low-incomes, with a family of four earning less than $53,000 a year. Women, immigrants and Blacks are overrepresented as essential workers. Roughly 61 percent of women, 28 percent of immigrants and 17 percent of Black people are considered essential workers.

Reynolds explained that Black and Hispanic people are more likely to live in tightly cramped homes and use public transportation, which leads to higher infection rates of communicable diseases, including coronavirus.

VACCINE HESITANCY

Experts like Reynolds believe low vaccination rates can be partly explained because of vaccination hesitation. “There’s a high degree of distrust in minority communities of the healthcare system, vaccines, government,” he said, “and there’s a lot of history in place that reinforces some of that distrust.”

Although he believes the 1932 to 1872 Tuskegee syphilis experiment — in which Black men, without their knowledge, were given a placebo rather than a promised treatment to see what would happen if the veneral disease went unchecked — explains the distrust that many Black people feel toward the healthcare system, Reynolds does not think it’s the only explanation. Healthcare disparities, coupled with a general lack of cultural competence among many healthcare workers, also are factors.

When Black and Hispanic residents go in for routine healthcare procedures, they often do not see workers who resemble them, and many times they need translators. If there are no available translators, non-English speaking Black and Hispanic residents are put on a phone line. Reynolds said he believes these disparities reinforce the notion in their communities that healthcare has no place for them. “I’ve spoken to a lot of folks who have a fundamental distrust of vaccines and the medical establishment, and I want to be careful because we don’t want to be in a position of calling anyone who has questions about Covid vaccine as an anti-vaxxer,” he said. Reynolds said he believes health ad government experts should have an open dialogue with people of color and answer fundamental questions about the vaccine. He also said vaccine pop-up sites should be located in accessible places that the community knows and trusts, and community leaders who can promote vaccines should be enlisted to help. “I think it’s very easy to say, well, the community doesn’t trust it, they don’t want it. Actually, there’s a lot of people who do. You’ve got to make sure that that access is there,” he said.

State Sen. Kevin Thomas, a Democract from Levittown, represents the 6th District, whose constituents are a little over a third Black and Hispanic. His office, he said, has increased efforts to make the vaccine more accessible to people of color, hosting more vaccine pop-up sites, sending out mailings, and attending church and PTA meetings to spread the word about the vaccines and vaccination sites.

“In the very beginning, there was a lot of misinformation out there about the vaccine. We had to get over that hurdle,” he said. “We had to go into [Black and Hispanic] communities, talk about facts, and as more people got vaccinated that look like them, they start changing their mind.” Scott Brinton contributed to this story.

KEEPING THE OCEAN OUT OF YOUR YARD

Jones Beach is a wide stretch of sand, which should help insulate it against future sea-level rise, but not forever, according to scientists. Above, a view of the state park’s famed boardwalk.

BY MARJORIE ROGERS

Climate change could spell imminent disaster for many beaches, as rising sea levels threaten to gobble up sandy shores and force coastal communities inland, scientists warn.

Jones Beach isn’t a typical beach in that regard. Thanks to the natural current that sweeps sand from east to west and jetties that help it accumulate on the shore, Jones Beach is a very broad beach, with plenty of room for humans to sunbathe and build sandcastles — and will be in the near future, even as the ocean eats at the shoreline. Other parts of the park, however, may be more susceptible to climate change’s effects, and the results could spell more immediate trouble for Long Islanders. One of the lesser known and more vulnerable parts of Jones Beach State Park is its marshes. These coastal wetlands play a critical role in drainage and flood prevention for Long Island’s South Shore. After severe storms, marshland absorbs rainwater and helps keep the Island’s mainland from flooding. The marshes are also home to several different species, including wading birds, terrapin turtles and many species of plankton. Annie McIntyre, Long Island regional environmental manager for the New York State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, is one of the humans who takes care of Jones Beach and other state parks around the Island. She also works to educate students and park visitors about the biology of the parks. Her immediate concerns lie mostly with the marshes. “Sea-level rise is more going to impact our marshes before it impacts our beaches,” McIntyre said. According to her, marshes have the ability to adapt to gradual, natural rising sea levels. If the climate were changing at a slower rate, the marshes would have time to adapt, moving slowly inland. Human-created climate change, however, is causing the sea levels to rise rapidly, at a rate the marshes cannot keep up with. Long Islanders have also built on the land immediately surrounding the marshes, further inhibiting their ability to escape rising sea levels. This means that the marshes, which have been home to wildlife and prevented flooding for centuries, are at risk of disappearing. “We have built on pretty much every marsh,” McIntyre said. “Because [sea level] is rising quickly and [the marshes] really can’t move because we’ve built structures alongside the marshes, they’re just going to shrink. Those animals will have nowhere to go.” Further down the road, as human-produced climate change causes sea levels to rise, Jones

Beach could eventually become Long Island’s Atlantis: an underwater destination lost to time. According to a graph from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, if sea levels were to rise by five feet within the next 30 years, most of Jones Beach would be underwater

With Jones Beach’s marshes and shorelines gone, Long Islanders would experience flooding more often and more severely. Wildlife within the park would have nowhere to go, and their absence would disrupt fishing and other recreational activities.

Annalisa Peña, president of Leaders for Environmental Action and Fellowship at Hofstra University, said Long Islanders need to start preparing for the effects of climate change. “We’re coming to a point where it’s past being preventative,” Peña said. “Now we have to be reactive to what is happening . . . We have to focus on infrastructure to protect us from inevitable things.” Peña has watched climate change affect Long Island, noting that although she is only 20 years old, she has noticed the shore move inland considerably. Revisiting beaches she used to frequent as a child, she sees how the shoreline has changed and shrunk. Jase Bernhardt, a professor of geology, environment and sustainability at Hofstra University, said beach erosion and change to shorelines is normal. He spoke of the time the record-breaking New England Hurricane of 1938 tore through Long Island; not only did the storm reshape the barrier islands, but the hurricane caused such severe flooding that it cut off parts of eastern Long Island from the mainland. “There’s always going to be those sort of events,” Bernhardt said, noting that the occasional drastic storm is inevitable. He added, however, that these events under climate change could become more tumultuous and wreak even greater havoc on coastal areas such as Jones Beach. Like Peña, he recommended infrastructure reinforcements to help maintain the beach as the climate changes. “With the sea-level rise in the background, there’s going to be more impactful surge events,” Bernhardt said. “Overall, there’s going to be the need for more and more investment in this. I think that’s what a changing climate is telling us.” McIntyre said she believes the effects of climate change are already happening on Long Island. The much more frequent and violent storms that the Island has experienced in recent years are not merely coincidental in her book. Storms with a 1 in 100 probability of occurring within a given year have been happening more frequently in recent years, which is a symptom of a changing climate. “We had a 100-year storm, and then 10 years later, we had a 50-year storm,” McIntyre said. “I don’t think that’s how it’s supposed to work.” McIntyre said little steps to be more fuel efficient could help combat climate change. Idly running one’s car engine when parked in a lot or drive-thru, for example, burns fossil fuels unnecessarily, and the carbon emissions from small wastes such as this can add up quickly. She does not believe people need to make drastic changes to their lives to make a difference, but rather be more aware and take small steps each day to use less energy and reduce waste. “I don’t think that the sledgehammer is the way to go,” McIntyre said regarding making lifestyle changes for the sake of saving the Earth. “Do small things, like turn the light off when you leave the room [or] use less electricity. Small things like that are pretty easy.”

The marshlands to the north of Jones Beach are in danger of sinking below water because of sea-level rise, scientists said they fear. These wetlands are home to numerous bird and marine species, and serve as breeding grounds for both.

THE ABOMINABLE

Southern Pine Beetle

How one little pest is setting Long Island up for disaster. These pesky beetles can destroy entire pitch pine forests, as they did in one part of the Pine Barrens.

BY MARJORIE ROGERS

In Eastern Long Island near the Hamptons lies a dense forest known as the Long Island Pine Barrens. In addition to the beautiful scenery they create, the pitch pine trees of this massive forest play a little-known and critical role in protecting Long Island’s water supply. The aquifers responsible for supplying most of Long Island’s water supply sit underneath the forest, protected and purified by the pine trees on the surface.

However, these pine trees are in trouble, because they are also the choice snack and nesting location for an invasive insect species known as the southern pine beetle. Olivia Calandra is a conservation technician with the Nassau County Soil and Water Conservation District. She works to combat the spread of the southern pine beetle and has witnessed firsthand how these bugs tear apart pitch pines. “They burrow under the outer bark of the tree, and then they lay their larvae there,” Calandra explained. “As the larvae are growing, they create s-shaped galleries, basically eating under the bark in these galleries… That makes it so that nutrients and water are unable to get from the bottom to the top of the trees.” Beetle infestation has led to deforestation in the Long Island Pine Barrens. Calandra expressed concerns about the declining pitch pine population. “It’s really important to protect the Pine Barrens,” she said. “When the water comes down in the rain, the trees filter the water through their roots and it creates groundwater. Having all these trees there is actually cleaning our water, so it’s really important that we protect this area.” Without the pitch pines acting as a buffer between the land and sky, the aquifers that supply Long Island with drinking water could become more susceptible to nitrogen pollution from landfills and farms. Water with high levels of nitrates has been known to cause many illnesses, including blue baby syndrome, which can cause permanent brain damage in infants. But how did the southern pine beetle, a native to the Southeast and Mexico, become year-round New York residents? According to Calandra, the bugs are now able to survive Long Island winters, which have become milder over the years because of climate change. “We’re having a lot more pests come up here because they’re able to survive now,” she said. “They’re not dying anymore [in] harsh winters. They’re able to survive all winter.”

With climate change enabling the southern pine beetle to survive on Long Island, conservationists like Calandra have an increasingly critical job protecting pitch pines — and ultimately, Long Island’s water supply — from destruction.

Southern pine beetles steadily destroy forests like this one on Long Island. An intact pine forest in Eastern Long Island. Photos courtesy of Long Island Pine Barren Society

EDUCATING TO SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT

BY CLAIRE BLAHA

Many organizations across Long Island aim to get everyone involved in protecting the natural world and learning to live alongside it. “In order to properly protect our environment, it’s important for us to understand it and our relationship to it,” said Jimena Perez-Viscasillas, the New York outreach coordinator for the Long Island Sound Study’s National Estuary Program. “Education is a good first step.” The Long Island Sound Study provides information and programs for people to learn about the environment around them and their effect on it. “Nitrogen pollution is affected by fertilizer use on people’s lawns,” Perez-Viscasillas said. “What we try to communicate to the general public is the best way to take care of your lawn in an environmentally friendly way.” Other organizations also focus on providing information and resources, specifically in a classroom setting, in order to give children an environmentally conscious education. Ron Geraldi, an environmental educator with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, tries to simplify a complex issue like sustainability for students with programs like “Where Is Away?” “The title of the program comes from the idea that we all produce garbage, and we throw it away, but there’s still a place that it goes,” Geraldi said. “And so we take them through the entire process of the waste stream, and we talk about other things we can do to interrupt the volume of waste each of us individually produces.” This is just one example of a program that Geraldi conducts to teach students practi-

High school students work to save the natural world with Students for Climate Action. Photo provided by Melissa Parrott.

cal sustainability measures. “It’s not a Greta Thunberg crusade across the world, which hopefully will bear fruit, but that’s kind of difficult to do for the individual,” he said. A BioBlitz, taking pictures of flora and fauna found in an area in order to learn more about it, also presents a pragmatic way to engage with the environment. These photographs can then be uploaded into an app called iNaturalist. “Basically it’s like a network of naturalists, so other people will see what you posted, and they can help you identify it,” Perez-Viscasillas said. This app helps the Long Island Invasive Species Management Area identify invasive species and locate them on Long Island. Anyone has the ability to educate him or herself and get involved with protecting and conserving the natural world, whether it’s through program participation, volunteering or even direct interaction with legislation that promotes change. Melissa Parrott is the founder and executive director of Students for Climate Action, a non-partisan organization with high school chapters across Long Island and in Texas and Massachusetts. Students work directly with their elected officials and urge them to transition to renewable energy and environmentally friendly practices. “We meet with town, county, state and federal officials, and we educate them on the climate issue and the solutions,” Parrott said. These high school students try to encourage officials to implement legislative change that can positively affect the environment.

“Education and outreach is so important to help others be a part of the bigger picture solution, but when you change policy, you’re creating action and law,” Parrott said. Whether it’s through hands-on programming or taking legislative action, everyone should learn and understand the natural world and their effect on it. And environmental change can only happen if it’s approached from every angle and by the youth who will be directly impacted by the change. “We give them the option of understanding what’s around them,” she said, “so when they grow up and they become parents, voters and landowners, they have a holistic approach to how to manage the natural world around them, whether it’s how they treat their lawn or their neighbors.”

BY AUGOSTINA MALLOUS

Long Island’s beaches are visited by millions of people every year, and Long Islanders take pride in the beautiful scenery and serene atmosphere that we call home. Unfortunately, scientists say that our beaches, saltwater marshes and infrastructure will be threatened by storm surges and sea-level rise in the near future. You may be wondering how you can help prevent that from happening, so we have gathered 12 nonprofit organizations that strive to restore and preserve Long Island’s environment so you can become a part of the change.

KEEP IT CLEAN AND GO GREEN

THE SAFINA CENTER

The Safina Center advances the case for life on Earth by fusing scientific understanding, emotional connection and a moral call to action. The center blends science, art and literature in the form of books and articles, scientific research, photography, film, sound-art and spoken word.

FRIENDS OF CALEB SMITH PRESERVE

The Friends of Caleb Smith Preserve runs several events to benefit the 543-acre Caleb Smith State Park Preserve in Smithtown. The park operates a nature museum with interactive displays, environmental education and recreational programs, cross-country skiing and snowshoeing trails, fly fishing, and guided nature walks.

MORICHES BAY PROJECT

The Moriches Bay Project is an aquatic restoration program created with a mission to improve the water quality in Moriches Bay and increase its environmental productivity. By working to re-establish populations of shellfish and eelgrass, the project strives to stem the tide of pollutants that have flooded the bay and filter out the excessive nutrients that are feeding harmful brown algae blooms.

THE GARDEN CONSERVANCY

The Garden Conservancy is a national organization dedicated to preserving America’s gardens for the education and enjoyment of the public. They seek to develop and deepen public appreciation of gardens as integral elements of our national artistic and cultural heritage. The Open Days program serves as the primary educational outreach for the conservancy and is a major component of the mission.

OPERATION SPLASH

Operation SPLASH is dedicated to bringing back the bays through the cleanup of local waterways, activism and education. Volunteers have rescued more than 2 million pounds of trash, marine debris and other hazards from Long Island’s beaches, bays and waterways.

COASTAL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION SOCIETY OF L.I.

This organization’s mission is to promote and foster understanding of coastal ecosystems through research and education. If you are interested in animal watching and research, this organization allows you to do just that by traveling to the outer islands of eastern Long Island, Cupsogue Beach, Montauk and other areas to observe seals, whales, dolphins, porpoises and more.

HUNTINGTON-OYSTER BAY AUDUBON SOCIETY

Huntington-Oyster Bay Audubon is an all-volunteer chapter of the National Audubon Society and serves more than 1,000 members in Huntington and Oyster Bay townships. It works to protect wildlife and preserve habitat through conservation action, education and ethical nature exploration. HOBAS offers regular beach cleanups, habitat restoration projects, naturalist trips, hiking adventures and prestigious speakers to address conservation issues at monthly meetings.

SUSTAINABLE LONG ISLAND

Sustainable Long Island is a non-profit organization advancing economic development, environmental health and social equity. Sustainable Long Island works as a catalyst and facilitator of community planning for the betterment of all Long Islanders.

LEADERS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION AND FELLOWSHIP AT HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY

This is a student-run organization that promotes the preservation of the environment while taking action to reverse the damage caused by humans on Earth. Hofstra students can practice deliberative dialogue and educate themselves about the current climate crisis.

PARKS & TRAILS NEW YORK

Parks & Trails New York is dedicated to improving our health, economy and quality of life through the use and enjoyment of green space. PTNY has worked with hundreds of community organizations and municipalities to envision, create, promote and protect a growing network of parks and more than 1,500 miles of greenways, bike paths and trails throughout New York State.

CITIZENS CAMPAIGN FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

CCE was formed by a small group of citizens concerned with the need for public involvement in developing environmental policies. The group engages in extensive education, research, lobbying and public outreach. One of its primary goals is to help people increase their influence and participation in important environmental campaigns.

SOUTH SHORE AUDUBON SOCIETY

The mission of South Shore Audubon Society is to promote environmental education; conduct research pertaining to local bird populations, habitat and wildlife; and to restore the environment. The group does this through responsible activism for the benefit of both wildlife and people.

Trips to Hofstra’s greenhouse, social media challenges, guest speakers and open discussions are only some of the activities you’ll get to be a part of in LEAF. Photo by Bill Belford.

The Target parking lot in Westbury. Photo by Athena Dawson

PPE POLLUTION IS NEVER PRETTY

BY ATHENA DAWSON

Long Island legislators and sustainability experts are concerned about pollution unique to the pandemic. Discarded gloves and masks are everywhere, from parking lots to parks. This is the reality of the new environmental issue caused by Covid-19 — personal protection equipment pollution. Since the start of the pandemic, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Protection has advised people to wear face masks, many of which are not reusable.

Annetta Vitale, a Hofstra University sustainability professor, said discarded masks and gloves enter Long Island waterways through storm drains, and antibacterial sprays and hand sanitizers may increase the prevalence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the environment.

Vitale is a member of a committee for the Blue Way, a South Shore aquatic kayaking trail. “At the meeting, people from the various stakeholder organizations expressed a concern about the increase in this PPE that they’re finding in the environment,” she said.

Similarly, some Long Island Legislators have realized how this issue is affecting the environment. Nassau County Legislator Joshua Lafazan drafted a bill last May to prohibit PPE littering in Nassau.

“My own bill passed in Suffolk County and still hasn’t passed in Nassau County…” he said. “My bill will serve as a deterrent to make sure that people think twice before littering PPE.” In addition to a fine, those found littering would face a community service requirement.

Hempstead Supervisor Don Clavin said the town is pushing on social media to remind people to throw away PPE properly.

#PLANT WISE

BY ROBERT TRAVERSO

Emvironmentally friendly eateries sprout up on Long Island.

Questions about the environmental cost of raising animals for food raced through the mind of Pamela Kambanis, co-founder of the Dix Hills-based vegan eatery Plant Wise, while watching a documentary nine years ago. “When I watched these documentaries, it was like the blinders had been taken off... I said to myself, ‘I don’t feel comfortable eating this way,” Kambanis said, referring to eating meat and dairy products. Kambanis’ experience is common: Documentaries that focus on the environmental consequences of animal agriculture inspire many to go plant-based, adopting a diet that is growing popular in the U.S. Pamela and her partner Alex, who co-founded Plant Wise with her, decided to go vegan for health reasons. Only later did they discover the benefits for the environment brought about by plant-based eating. “That’s what made it a lasting change,” Pamela said.

She stressed that her journey to veganism is part of a larger change in consciousness. “People are starting to understand how their choices — how they eat, how they live their lives — how that affects so many other things in the world,” Kambanis said. Pamela and Alex opened Plant Wise to make it easier for Long Islanders to eat healthy food daily and make going vegan less overwhelming. Plant-based eating was less common on Long Island when Plant Wise opened, but the eatery’s popularity has grown over the years. In fact, Plant Wise’s success was at an all-time high before Covid-19, Kambanis said.

Because of the rising popularity of plantbased eating, Plant Wise is planning the creation of a franchise program, expanding on the Island and beyond, to continue helping others adjust to adopting a plant-based diet. Kambanis acknowledged that this change is challenging for many people, but said it drives Plant Wise’s mission: to encourage people to eat one plant-based meal per day. “It can be overwhelming to try to change a whole lifestyle, and it can be difficult for people based on where you live and things that like that to change everything you eat overnight,” Kambanis said. “But focusing on something simple as one plant-based meal… it can have a positive effect on so many different aspects of your life and the world as a whole — especially the climate.” “The major thing you can do for the planet and for the environment is to change to a plant-based diet,” Kambanis said. “And we’re hoping Plant Wise can help in that way.”

Pamela Kambanis and her partner Alex co-founded Plant Wise to make going vegan less overwhleming for Long Islanders.

“The major thing you can do for the environment is to change to a plantbased diet.” - Pamela Kambanis