4 minute read

People Lived Here: Documenting the Lives of Those Treated at the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum

By KATHARINE ALLEN, Director of Outreach and Engagement

Advertisement

Harriet J. Gray, a 35-year-old woman, was a mother and wife of the builder of the original asylum building.

Angelina and Louisa Burrel two women in their 30s, were sisters who immigrated from France.

Anthony, a 50-year-old man, was enslaved by Franklin J. Moses, Senior.

Samuel G. Able, a 10-year-old boy, was the son of a farmer who fought for the Confederacy.

John A. Newton, a 25-year-old man, became a sign painter like his father, and decades later, Sarah A. Newton, his mother, was a 72-year-old widow and homemaker.

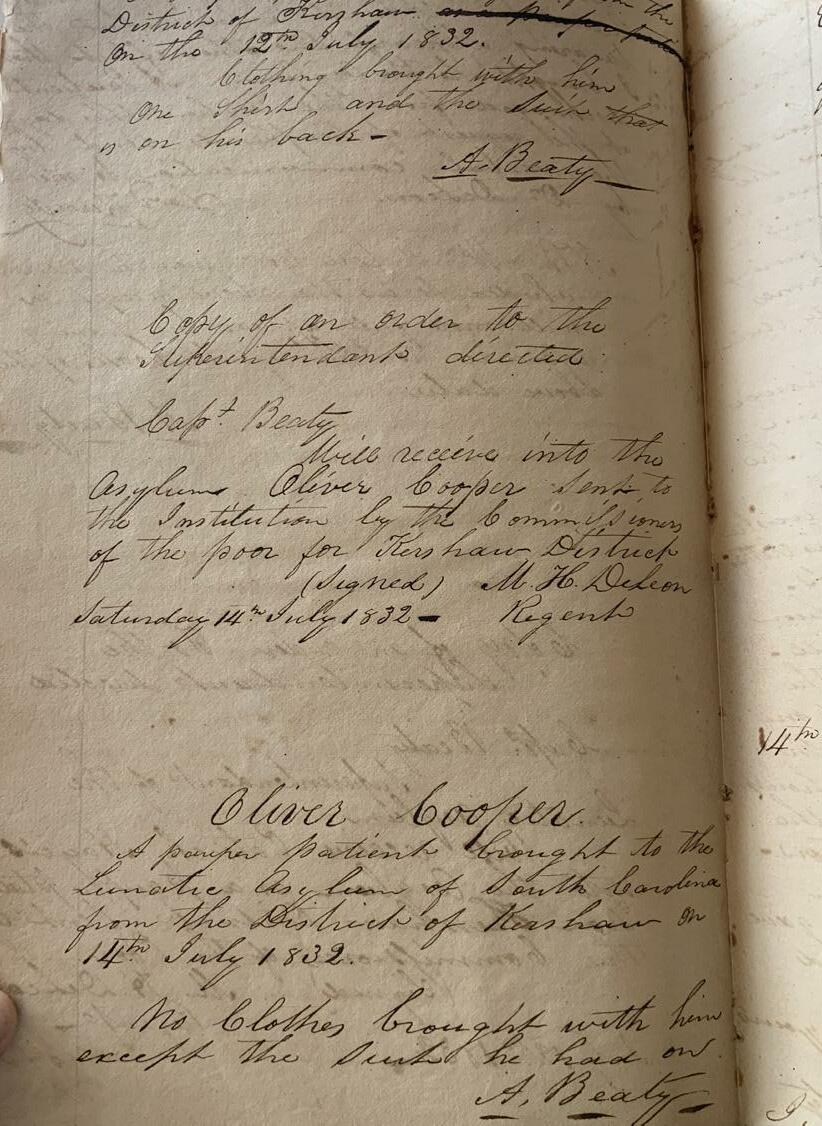

These are just a few of the people committed by family, enslavers, doctors, and government officials to the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum during the 19th century. Although doctors and attendants treated them vastly different based on their race, gender, social class, and reason for commitment, each person eventually found themselves living in confinement and at the mercy of others who would decide whether they could, or should, ever return to society.

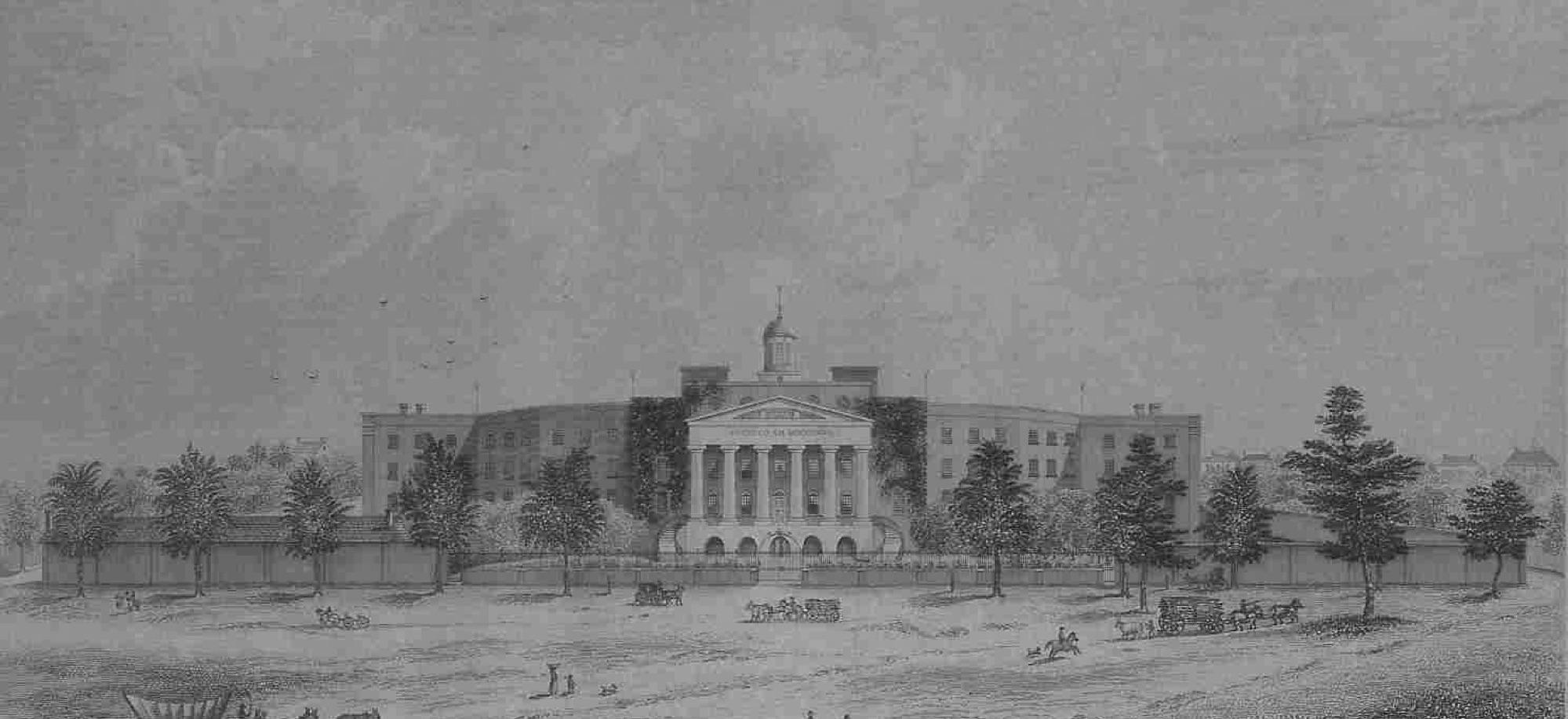

Some, including Harriet and the Burrel sisters, lived and died in the Mills Building at a time when the asylum comprised a single square block. Others, including John and Samuel, were among the first patients treated in the oldest sections of today’s Babcock Building, years before that sprawling facility was completed or renamed. And some, including Anthony, were allowed to live in neither place, instead finding themselves confined in makeshift, wooden structures, segregated and isolated from others on account of their race, status, or symptoms. Each of these people, and thousands more, had a life before being sent to Bull Street. Why then, do we not know more about who they were?

PEOPLE, NOT JUST PLACES

In past projects, Historic Columbia focused on documenting, preserving, and sharing the history of the buildings that once comprised the asylum, and later, those of the much-expanded state hospital. The Babcock and Mills buildings in particular stand as physical embodiments of one of the nation’s first state asylums, and their architecture reflects how the treatment of physical and mental disabilities changed over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, this lens can and often has dehumanized and reduced the people treated here to statistics. For instance, between November 1850 and November 1851, the asylum received 55 new patients, for a total of 176 treated that year. Of these, 40 were deemed cured and nine died. Of the 127 remaining, 68 men lived in male wards that were at capacity, while 59 women occupied female wards that were almost full. This overcrowding would soon justify the construction of the new asylum building, known today as The Babcock. These dates and numbers provide some context but no connection to the people who defined the asylum—its patients.

BEHIND-THE-SCENES TOUR AT THE BABCOCK

February 25, 2023 historiccolumbia.org/the-babcock t

Explore the past, present, and future of the former South Carolina Lunatic Asylum at Historic Columbia’s Behindthe-Scenes Tour of The Babcock. Participants will learn how historic uses have informed its current preservation and restoration. Thanks to our partner, Clachan Properties, participants will have an exclusive opportunity to walk through several sections of the rehabilitated building and learn about life at the site over the last 140 years. The tour will conclude with comments from Hughes Development Corporation about the future of the BullStreet District followed by beverages, courtesy of Peak Drift Brewing Co., and snacks.

For example, among those 59 women was widow Mary P. Allston, born in 1784 and committed by her grandson, Theodore S. Gourdin, in 1848. As Gourdin debated taking this step, Mary’s cousin and future governor R.F.W. Allston wrote to him that “she would be surrounded by as much care and attention to her well being and considerate kindness....as in any place of the kind.” Gourdin must have agreed, and Mary found herself living in the Mills Building just 30 days later.

Almost three years later, family friend and future governor, Benjamin F. Perry mentioned Mary in a letter to his wife:

Friday morning I visited with fifteen or twenty Senators & members of the Legislature the Lunatic Asylum & passed through all the buildings, saw all of the inmates & walked over the grounds & garden & green house, all of which are interesting. I saw old Mrs. Alston. [sic] She looked comfortable & happy. In one room a sitting room or parlor I saw fifteen or twenty women, all neatly dressed & well behaved. No one would have supposed that they were crazy.

The scene painted by Perry, one of moral treatment, beautiful surrounds, and progress towards sanity, aligns with the asylum’s institutional reporting. Treatment records confirm that she had a private apartment, private nurse, and could request whatever food she wanted. While her standard of care, objectively, was much higher than most patients, Mary herself felt differently about her circumstances. In late 1848, she wrote to her three grandsons that, “My poor weak shattered Nerves are truly harrassed [sic] and tortured by being in a Madhouse or perfect Bedlam! [I] would now rather suffer the most excruciating death than be confined here.”

PEOPLE, NOT PATIENTS

Mary’s experience at Bull Street is unique in that she could and did record her own thoughts on her confinement, and that this account has survived into the present. Thousands of other patients did not have this ability, and today all that remains are patient numbers, names, and sparse treatment notes. Now, in partnership with Able South Carolina, Historic Columbia has begun the task of finding out who these people were before and during their confinement, and ultimately what happened to them. With support from South Carolina Humanities, we are collectively creating a series of biographies of people who would eventually become patients, including those mentioned at the beginning of this article. Our goal is to recenter individuals in the stories we share about Bull Street, and in doing so destigmatize disabilities of all kinds. The website will launch later this spring, so be sure to subscribe to Historic Columbia’s monthly newsletter for updates.