47 minute read

Prostitutes, Plays and Public Policy: Representations of Enslaved Sex Workers and Their Impact on Regulations in Ancient Rome

from Hirundo XIX

MAIYA WERBA

While evaluating the interplay between media representation, public discourse, and public policy is a common feature of cultural discussion in the present day, little work has been done to assess this relationship in ancient Rome, especially in the context of enslaved sex workers. The lack of scholarly attention presents an unfortunate gap in current knowledge insofar as a deeper understanding of how these respective institutions influenced each other would provide a deeper understanding of each individual element therein. Sex work was a widespread institution in ancient Rome, and it is likely that most sex workers were enslaved.1 Indeed, beginning during the reign of Caligula (37-41 CE), sex work was taxed by the state; therefore, it was integrated into society in a fundamentally different way than in modern times.2 The purpose of this paper, then, is to gauge the kind of relationship which existed among public discourse, media representation, and the regulation of enslaved sex workers. Ultimately, a high degree of correlation existed between these institutions, both in cases where the notion of a scapegoat was propagated in order to avoid the incrimination of elites as well as in cases characterized by a general anxiety surrounding free women being subjected to the same treatment as enslaved sex workers. In terms of source material, this paper focuses on representations of enslaved sex workers in Roman media, public discourse, and legislation. In regard to representations in the media, due to the small and highly trope-like nature of enslaved sex workers in plays, as well as the constraints of this paper, I will be focusing primarily on the works of Plautus, though other examples will be brought up as necessary. In regard to public discourse, I will mainly make use of recorded speeches from public events relating to enslaved sex workers. As the nature of such sources necessarily limits the perspective of public discourse to that of elite Roman men, I will also draw on archaeological remains in order to ascertain divergent aspects of public discourse. In terms of legislation, I will make use of legislation that refers to sex work and enslaved sex workers that affected their regulation, social status, or sale. Thus, legislation referring to sex workers in general will be considered. Similarly, while there were varied kinds of sex workers, this paper, as it focuses on those enslaved, will not consider high class courtesans or free women engaged in temporary sex work, even if they were also regulated by these laws.3 Since it is likely that the majority of sex workers were enslaved, regulations on sex workers as a whole should be considered and evaluated as part of regulations against enslaved sex workers unless, as will be discussed later, the legislation itself specifies otherwise. Additionally, this investigation will be limited to the 1st century CE. The connections between these diverse issues of representation, discourse, and policy will be evaluated in a series of case studies relating to brothel depictions, pimps, romantic relationships with enslaved sex workers, and violence against them. In turn, for each of these subtopics, I will delineate their media representations, public discourse, and legislation to examine where commonalities emerge. Before delving into our discussion, it is imperative to establish specifically who enslaved sex workers were and where they came from. The majority of enslaved sex workers were drawn from those captured in war and conquest, from those who were already enslaved, and from those “kidnapped by robbers and pirates.”4 Within the already enslaved population, one source of sex workers was vernae, house-born slaves.5 Likewise,

Advertisement

1 Thomas McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution in the Roman World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004), 73. Most sex workers were slaves or slaves of more legal interest (likely both) (McGinn, Economy of Prostitution, 59), especially because unlikely free women could have been compelled into sex work (McGinn, Economy of Prostitution, 60). 2 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 73-6 3 Ria Berg, “Unveiling Roman courtesans” in The Roman Courtesan, Archaeological Reflections of a Literary Topos, eds. Ria Berg and Richard Neudecker, Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae, Vol. 46 (Roma: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae, 2018), 50. 4 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 55. 5 McGinn, 57-8.

many sex workers, especially those in brothels, were slaves, as it is unlikely that free women could have been compelled into sex work as slave owners and pimps were the ones who forced sex workers “to work a great deal for little reward.”6 However, not all sex workers worked explicitly in brothels — those in brothels were “only a fraction of the number of sex workers working in the city.”7 Therefore, there were numerous enslaved sex workers of different backgrounds and occupying different spaces in ancient Rome. In turn, it is important to note that this paper cannot speak to all of their experiences, but only those perceived to be most common in Rome those most prevalent in legislation, media, and discourse. The widespread nature of sex work can be attributed to the many varying forms that sex work operations took. There were a wide range of establishments which offered sexual services: tabernae, meritoria, cauponae, stabula, deversoria, synoecia, thermoplia, ganeum, ganea, and gurgustium, though the latter three are “low dive” and most explicitly associated with sex work.8 It is difficult to distinguish other lower-class institutions, such as tabernae or thermopolia, from brothels based on either archaeological or literary sources.9 The pervasiveness of sex work in these spaces created an association between this work and lower-class spaces and housing, which were already disliked by Roman elites out of class prejudice.10 Nevertheless, there was still no “moral zoning” and, for the most part, brothels or similar establishments were able to operate anywhere.11 This reality highlights a disconnect between public discourse and legislation: although the public complained about the existence of these spaces, they were both legal and prevalent in Roman society. In fact, many upperclass Romans owned the land on which brothels operated and derived profit from their rent.12 These spaces were regulated by aediles, who allowed them to operate and whose main responsibility was to “preserve public order.”13 The aediles ran a registry of sex workers, which was discredited after a scandal in 19 CE, and ensured status distinctions by “enforcing the use of appropriate clothing,” likely due to Augustan adultery legislation14 Such oversight suggests that enslaved sex workers were, to a degree, visibly different from others, but not to the extent that the government needed to take additional measures to identify them. In turn, brothels and brothel-adjacent spaces were diverse and dispersed throughout the city with evidently little regulation as long as they did not actively disrupt public order. The brothel itself played a significant role in the public image and narrative of sex work. Brothels were seen as dirty in the public eye and while this might have been true, it is unlikely that they were all as vile as some accounts present them to be, as public accounts were affected by classist rhetoric.15 In terms of what the brothels looked like: a “sex worker worked in a booth or small room (cella) within the brothel with her price outside her door.”16 This was a space for short, evidently transactional, visits. Brothels also provide a mediated insight into the perspective of sex workers through graffiti remains in which sex workers talk about their clients. However, it is important to “acknowledge the polysemous nature of graffiti: not only can they lie, create fictive personas, and play tricks on readers… they could have different meanings to various individuals.”17 One particular commonality among brothel graffiti is the prevalence of names and the mention of the sexual capabilities of clients; however, many prostitutes “may have been expected to write graffiti supporting their clients’ claims to masculine sexuality.”18 This dynamic created a public narrative in which enslaved sex workers were sexualised and praised the sexual skills of their clients. Thus, it would be faulty to assume that enslaved sex workers were able to honestly express themselves through graffiti. In any case, such graffiti would have played a significant role in the public understanding of enslaved sex workers.

6 McGinn, 59-60, 73. 7 McGinn, 222. 8 McGinn, 16. 9 McGinn, 16. 10 McGinn, 17-20. 11 McGinn, 79. 12 McGinn, 31-2. 13 McGinn, 149. 14 McGinn, 152. 15 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 84. 16 McGinn, 39. 17 Sarah Levin-Richardson, The Brothel of Pompeii: Sex, Class, and Gender at the Margins of Roman Society (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 56. 18 Levin-Richardson, The Brothel of Pompeii, 115.

One common trope among representations of enslaved sex workers is that of their evil and abusive pimps, who usually feature as the villains of plays. The common narrative in plays, especially in comedy, deals with a “dishonourable pimp,” as is the case of Ballio in Pseudolus. 19 In particular, Ballio’s turpitude is “a matter of his status,” thus an equivalency is drawn between his vocation as pimp and his immorality.20 For example, when asked why he sold Calidorus’ girlfriend, he replies, “I felt like it and she belonged to me.” He proceeds to laughingly accept all the insults that Calidorus and Pseudolus direct at him, even accusations of murdering his parents.21 Likewise, in Pseudolus, Calidorus specifically laments the lack of regulation of pimps and their consequent malicious behaviour.22 This passage in particular speaks to an attempt to create a causal relationship between cultural rhetoric and policy: it implicitly agitates for changes in public policy through literature. Thus, it speaks to an engagement between public discourse and literature, in this case on the issue of pimps. Similarly, the threat of being owned by a pimp is also present in these plays: Synecrastus, for example, sees being owned by a pimp as the absolute worst fate.23 In this way, responsibility for the misfortunes of enslaved sex workers was either attributed to or blamed on their pimps, rather than their clients or the broader system of sex work in Rome. The portrayal of pimps as evil and to be feared characterizes other characters as more moral in comparison. Therefore, this narrative propagated in plays representing enslaved sex workers serves to absolve the public of any responsibility, instead providing a clear villain who can be held responsible. Pimps were regulated both in terms of their behaviour and status by the Roman government. The Lex Iulia of 23 CE prevented the senatorial elite from marrying below their class, and freeborn persons from marrying people like sex workers and pimps.24 As well, pimps were not allowed to hold public office; however, they were still able to exert control over their slaves and keep their earnings.25 To avoid legal restrictions and incrimination, elites would use intermediaries and pimps. This could create a scenario where “slave sex workers might form part of the peculium of a slave pimp, who himself might be the vicarius of another slave or the property of a freed or freeborn manager,” or another variation of a “middle man” to absolve the elite owner of involvement.26 Such a dynamic ties directly into the narratives we have seen surrounding pimps in public discourse and media representation, where they are portrayed as fundamentally wrong and beyond redemption. Therefore, there was little new regulation past punishing pimps; furthermore, this enabled elites to avoid the consequences of association with enslaved sex workers as their middle man pimps suffered instead.

Nevertheless, although enslaved sex workers without a respectable heritage are rarely rescued in plays, they are occasionally given the space to criticize their masters. For example, in Plaut’s Persa, Sophoclidisca, an enslaved sex worker owned by a pimp, criticizes her master while asserting her intelligence by mocking him for not being able to “figure out my brainpower, you dumb baby. Can you shut up? Could you stop nagging?”27 First of all, Sophoclidisca’s pronouncement of her intellectual superiority over her master’s speaks to a common trope in Roman plays in which slaves mock their masters. Sophoclidisca’s speech, however, is particularly significant given the fact that she says it directly to her master, rather than as an aside or in conversation with another character. Second, the comedy of this moment is seen in the assertion of an enslaved sex worker knowing better than her owner. Third, it is rare for enslaved sex workers to speak, let alone to their masters. The fact that Sophoclidisca explicitly tells her master to stop talking would have stood

19 Roberta Stewart, “Who’s Tricked: Models of Slave Behavior in Plautus’ Pseudolus,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 7 (2008): 69. 20 Stewart, “Who’s Tricked,” 77. 21 Plautus, Pseudolus, ed. and trans. Wolfgang de Melo, Loeb Classical Library 260, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), lines 345-50. 22 Plaut. Pseudolus, lines 201-4. 23 Amy Richlin, Slave Theater in the Roman Republic: Plautus and Popular Comedy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 229. 24 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 72; Gaius, Institutes of Roman Law by Gaius, trans. Edward Poste, 4th edition, ed. E.A. Whittuck, M.A. B.C.L, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904), Justinian’s Codification 66-8 (outlines various types of marriages with a clear indication that certain pairings would never happen). 25 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 37, 52. 26 McGinn, 36. 27 Persa (translated in Richlin, Slave Theater, 227).

out from other works.28 In turn, this rarity suggests that, while a cultural narrative of the sex worker who speaks out against their master existed, there was a common understanding that the sex worker with the intelligence to do so was rare. In this way, their representation did not align with narratives that demonstrated the agency of enslaved sex workers. In particular, the relationship between legislation and media representations of enslaved sex workers demonstrates a general desire to prevent the existence of any genuine connection between enslaved sex workers and elites. Significantly, when enslaved sex workers who are perceived to deserve their enslavement are freed, there is always an existential threat that enables their freedom. For example, in Pseudolus, Calidorus’ scheme to free his enslaved paramour, Phoenicium, occurs only because she is being sold to a Macedonian soldier; the fact that he will no longer have to access her motivates him to change her situation.29 In fact, their alleged love is undermined when Pseudolus reading her letter and “interprets [her name] literally and concretely in order to conjure up the image of her as sprawling in the writing tablet” in order to undermine the image of Calidorus as a “romantic lover” and his romantic idea of Phoenicium.30 Thus, a pattern emerges where enslaved sex workers are freed not out of genuine connection, but out of lust. Of particular significance here are the Ne Serva laws, which prevented men of a certain standing from marrying sex workers and put similar restrictions upon connections with pimps.31 This is especially noteworthy considering laws on manumission specified marriage as an acceptable reason for the freeing of a female slave.32 Therefore, enslaved sex workers would have been disproportionally harmed by this legislation as it reduced their likelihood of freedom. Likewise, women who had engaged in sex work are understood to be disgraced and lacking the same “virtue” of a Matrona.33 In particular, the cultural discourse surrounding this issue, mainly provided by the jurist Ulpian (c. 170-228), represents a sentiment against proper Romans uniting with infamous women.34 Therefore, a uniform narrative emerges across public discourse, media representation, and law in which romantic connections between elites and sex workers are either limited or entirely discredited. A further common trope surrounding the representation of enslaved sex workers in plays is that of the sex worker who secretly never deserved to be enslaved and is eventually rescued. For example, in Plautus’ Epidicus, the central characters are Telestis, a newly enslaved woman bought by a soldier who desires her, and Acropolistis, a slave freed by a man who believes her to be his daughter. Naturally, the end of the play reveals Telestis to be the true daughter and to have been wrongly enslaved the entire time.35 Throughout the piece, the enslaved Telestis is still described as worthy of being free.36 This suggests an underlying belief that being free was something people could perceive, even when one was wrongly enslaved. Moreover, this highlights “the ambiguous status of sex slave” and how their appeal “stems partly from the titillating fact that they might be respectable women,” look like respectable women, and “recently were respectable women before” they were enslaved.37 This element speaks not only to a hyper-sexualization of enslaved women, but also to the understanding that, in the context of plays, enslaved women were easy to exploit sexually. Likewise, since the enslaved women in such contexts will always be eventually rescued, their exploitation, while moving, is known to be temporary and, therefore, endurable. Those who are enslaved unjustly — respectable women — are given the opportunity to speak out against their oppression and abuse, such as in the case of Virgo, whose “words told the audience what it feels like to be threatened with a beating, and what it feels like to be sold, far from home one way or the other.”38 However, it is important to note that it is mostly respectable women, the unjustly enslaved, who are given the opportunity to express themselves. Enslaved sex workers who stay

28 See all of Plautus’ other plays, where women rarely talk, especially enslaved ones. 29 Plaut. Pseudolus, lines 40-5. 30 Stewart, “Who’s Tricked,” 73-4. 31 McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 289. 32 Gaius, Institutes, II 19. 33 Marcellus, “Digest, Book XXVI,” in Medieval Sourcebook: Corpus Iuris Civilis: The Digest and Codex: Marriage Laws (Fordham University). 34 Rebecca Flemming, “Quae Corpore Quaestum Facit: The Sexual Economy of Female Prostitution in the Roman Empire,” The Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999): 51-2. 35 Richlin, Slave Theatre, 257 36 Epidicus 43-4, trans. Richlin, Slave Theatre, 257. 37 Richlin, Slave Theatre, 257. 38 Richlin, 264.

enslaved, on the other hand, are rarely used as examples of pathos; rather, they primarily exist as examples of comedy, as in the case of Sophiclidisca. Therefore, the common trope of the respectable women being enslaved and rescued does not provide a genuine space for the pain of enslaved sex workers; rather, it highlights a fear for the safety of respectable women and a desire for enslaved sex workers. Such concerns surrounding female modesty and the need to protect Roman women from immorality were generally the dominant narratives in public discourse and legislation. Indeed, the fear of abduction and slave dealing networks around pirates, pimps, and trades were “linked in the popular imagination.”39 Suetonius notes that Mark Antony had his friends “pimp for him” and “accordingly obliged both matrons and ripe virgins to strip, for a complete examination of their persons,” like a slave dealer.40 This anecdote speaks to a similarly derogatory language, as seen earlier, in regard to pimps and the sale of slaves. It also speaks to a dislike, seen in plays, of the corruption of potentially respectable women by bringing them down to the condition of enslaved sex workers. In particular, the key issue was that female slaves were exploitable as sex workers, so any respectable women brought to that status would also face such exploitation. These narratives all speak to various ideas in public discourse which would provoke harsh judgment of sex workers insofar as they were considered a part of the licentiousness that was advocated against. Outside of fears of abduction, there was also a general concern about public spaces being too risqué, leading to a ban on women occupying certain seats at games or arriving too early.41 This emphasizes the desire to protect the modesty of respectable women by removing any potential exposure to sexual or corrupting people. Consequently, sex workers faced similar limitations such as bans from certain religious practices reserved for respectful women, although they did have their own holiday, the Nonae Capratinae.42 Such regulation provided a degree of status only for respectable women in contrast to, enslaved sex workers. The other major legislative changes in the 1st century were the aforementioned Ne Serva laws, which made it illegal for husbands to pimp out their wives – this regulation, however, had “no connection with (actual as opposed to prospective) sex work” and concern for slaves “provides only a partial explanation.”43 Significantly, this legislation does not explicitly demonstrate any sympathy for enslaved sex workers in public discourse; rather, it is specifically a compassion for women, who would otherwise be respectable, being subjected to an unfortunate and undeserved position. Conversely, respectable women who transgressed these moral boundaries were punished in public discourse. Cicero’s Pro Caelio (56 BC) reveals that the notion of being an enslaved sex worker could be used for character assassination and as a weapon against respectable women in general. For example, when Cicero discusses the potential innocence of Caelius, he references Clodia’s morality and behaviour as the standard by which either “[it] will supply us with the defence, that nothing has been done by Marcus Caelius with any undue wantonness; or else your impudence will give both him and everyone else very great facilities for defending themselves.”44 Here, Cicero associates Clodia “with a group [meterixes] technically forbidden to give evidence in court,” even though the designated Clodia is an elite Matrona.45 In turn, Cicero’s motivation in speaking to Clodia in this way is evidently to degrade her through this (erroneous) association. He continues, asserting that the charges in this case concern “one woman—both imputing enormous wickedness; one respecting the gold [received from Clodia]... [and] the other respecting the poison” used to try to kill Clodia.46 That Clodia is the victim in this crime and yet Cicero feels justified in attacking her character via claims of sex work suggests a serious and visceral response against sex workers in Roman discourse; otherwise, it would not be as effective to blame Clodia, the victim, to the extent that Cicero does in this speech. The conception that a woman who acts in an illicit manner permanently degrates her status exists consistently in Roman public discourse, such as in Seneca’s Controversia, where once again the association with sex work serves to alter a woman’s worth.47 Insofar as Cicero uses the perception of Clodia’s misconduct

39 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 56. 40 Suetonius, De vita Caesarum, trans, Alexander Thompson (London: George Bell and Sons, 1890), LXIX. 41 Suet. De vita Caesarum, XLIV 42 McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law, 25. 43 McGinn, 289. 44 Cicero, Pro Caelio, trans. C. D. Yonge (London: George Bell & Sons,, 1891), 50. 45 Matthew Leigh, “The Pro Caelio and Comedy,” Classical Philology 99, no. 4 (October 2004): 304. 46 Cicero, Pro Caelio, 51. 47 Flemming, “Quae Corpore Quaestum Facit,” 43-4.

in order to discredit her, this speaks to a fine line in Roman public discourse between respectable women who need to be rescued, as discussed above, and those who deserve to fall in social status. Such a belief also helps explain the obsession with protecting the virtue of respectable women: once gone, it could never be retrieved. In this way, we can see that a simple association with sex work was powerful enough to merit a fall in social status; this highlights the prevalence of a distaste for sex workers in public discourse and society. Consequently, a strong connection exists among the media, public discourse narratives, and the legislation that emerged in order to preserve the morality of free Roman women. The Ne Serva law criminalizing husbands who pimp out wives was driven more by anxiety than reality and was shaped “by literary convention or motivated by personal hostility.”48 This anxiety is clearly demonstrated in the tropes of plays, described earlier, where audiences are meant to sympathize only with women who do not deserve enslavement; it is also echoed in public discourse promoting modesty and regulations against women in certain spaces. Similarly, the “animus directed at pimps in general” suggests a contrast in Roman public consciousness regarding a moral understanding of the exploitation of sex workers as opposed to other dependencies. In essence, a belief emerged claiming that wives, instead of enslaved sex workers, had to be protected from villainous pimps.49 In turn, legislation sought to protect wives via laws such as those preventing husbands from being able to pimp them out or allowed them to sell their sexual labour.50 Evidently, this legislation follows the concerns of public discourse and media tropes, which in turn speaks to a strong correlation between the concerns of such discourse and tropes in the creation of legislation on this issue. Consequently, a dominant concern for respectable Roman woman was more important to legislation than other aspects of sex work which held stronger footing in reality. Furthermore, violence and exploitation are both common elements of plays relating to enslaved sex workers. This violence took on many forms, such as via pimps and owners, as discussed above, but these are not the only perpetrators. In fact, violence against enslaved sex workers is even perpetuated by their fellow slaves, such as in the case of Plautus’ Asinaria, where Libanus and Leonida “force the young owner Argyrippus and his sex worker amica to promise them freedom, beg them for money… the amica is made to call each of them sweet names and is asked to kiss and embrace them.”51 This event speaks to a common trope of casual violence against enslaved sex workers, and specifically that this violence was deeply intertwined with the sexualization of enslaved sex workers – the amica is not simply being attacked, but also sexually assaulted. Moreover, it is important to note that, when enslaved sex workers instrumentalize their sexuality to their own advantage, they are usually punished for it, as “women’s sexual power is both exploited and resented onstage.”52 This also highlights a difference between exploited male and female slaves: “female slaves, as you might expect, [do not] complain about the sexual use made of them by their owners, although male slaves commonly complain.”53 While female slaves were commonly and violently sexually exploited in plays, sex workers were, on the other hand, kept out of the home with their exploitation occurring in other spaces.54 This also speaks to a difference in the representation in plays between enslaved sex workers, slaves, and respectable women: this type of abuse only occurs in spaces occupied by enslaved sex workers and is, therefore, fundamentally different from the abuse occuring in domestic spaces.55 In turn, the kinds of violence experienced by enslaved sex workers in media representations are unique insofar as they are contextualized by both the pervasiveness of their exploitation and the spaces they occupy. The reality of enslaved sex workers regarding such violence closely follows their literary representation as they were subject to attacks from clients, pimps, and owners. Even though aediles were charged with maintaining order, violence was still fairly common in brothels, especially gendered violence.56

48 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution. 57. 49 McGinn, 73-5. 50 “Book XLVIII. Title V. Concerning the Julian Law for the Punishment of Adultery,” in Medieval Sourcebook: Corpus Iuris Civilis: The Digest and Codex: Marriage Laws, 2-4. 51 Richlin, Slave Theater, 216. 52 Richlin, 268. 53 Richlin, 268. 54 Richlin, Slave Theater, 276. 55 Richlin, 277. 56 McGinn, The Economy of Prostitution, 88-9.

In particular, “forced entry, or its attempt, into a brothel is a theme with a long history in Roman literature and” life.57 For instance, Ulpian believed a man was not liable if he broke down a sex worker’s doors due to lust and thieves enter independently and take her property; moreover, he portrays this as relatively common.58 This kind of violent visit to a brothel was a common feature of the comissatio. 59 In this way, we see violence against enslaved sex workers and their spaces as devalued in public discourse, as it did not acknowledge their pain. In turn, this can explain the lack of additional legislation against these attacks, as there was no sympathy to prompt a push for change. Overall, we see that an apathetic relationship existed among those with the power to prevent this violence – likely because they were the ones perpetrating it. In conclusion, the connection among public discourse, media representation, and legislation reveals a preference to focus on issues that do not require elites, who explicitly profited from this industry, to change, but, rather propogated the notion of cultural scapegoats in the form of pimps and a societal fear for free women who, in reality, never faced the danger that enslaved sex workers did. In particular, the consistency between cultural discourse and legislation speaks to a high correlation between these narratives. Similarly, while media representation displays greater variety than public discourse and legislation, the cohesion between this representation, legislation, and public discourse on particular issues suggests close ties between these various institutions. Ultimately, the interplay among these various cultural and societal aspects merits further investigation that could serve to provide a greater understanding of how cultural institutions, power dynamics and the law operated in ancient Rome in the context of enslaved sex workers and beyond.

57 McGinn, 89-91. 58 McGinn, 89-91. 59 McGinn, 91.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Berg, Ria. “Unveiling Roman Courtesans.” In The Roman Courtesan: Archaeological Reflections of a Literary Topos, edited by Ria Berg and Richard Neudecker, 41-65 Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae, Vol. 46. Roma: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae, 2018. “Concerning the Julian Law for the Punishment of Adultery.” In Medieval Sourcebook: Corpus Iuris Civilis: The Digest and Codex: Marriage Laws. Fordham University. Cicero. Pro Caelio. 56 BC. Translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A. London: George Bell & Sons,1891. Flemming, Rebecca. “Quae Corpore Quaestum Facit: The Sexual Economy of Female Prostitution in the Roman Empire.” The Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999): 38-61. Gaius. Institutes of Roman Law by Gaius. Translation and commentary by Edward Poste, M.A. Fourth edition, edited by E.A. Whittuck, M.A. B.C.L. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904. Leigh, Matthew. “The Pro Caelio and Comedy.” Classical Philology99, no. 4 (October 2004): 300-335. Levin-Richardson, Sarah. The Brothel of Pompeii: Sex, Class, and Gender at the Margins of Roman Society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019. Marcellus. “Digest, Book XXVI.” In Medieval Sourcebook: Corpus Iuris Civilis: The Digest and Codex: Marriage Laws. Fordham University. McGinn, Thomas. The Economy of Prostitution in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004. McGinn, Thomas. Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. Plautus. The Little Carthaginian. Pseudolus. The Rope. Edited and translated by Wolfgang de Melo. Loeb Classical Library 260. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. Richlin, A. Slave Theater in the Roman Republic: Plautus and Popular Comedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2017. Stewart, Roberta. “Who's Tricked: Models of Slave Behavior in Plautus's "Pseudolus".” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 7 (2008): 69-96. Suetonius. De vita Caesarum. Translated by Alexander Thompson. London: George Bell and Sons, 1890.

In Dialogue with the “Cold Pastoral”: Two Bucolic Ekphraseis of Theocritus and Keats

TARYN POWER

Bucolic is a genre obsessed with dialogue. Not only are interlocution and verbal competition defining motifs of the genre, but the genre itself is created through a process which Mathilde Skoie calls “eclectic reception.”1 Kathryn Gutzwiller defines the pastoral as “poetry about herdsmen, usually in dialogue, often involving erotic love, and commonly incorporating songs, such as singing contests between herdsmen, love serenades, or laments for the dead.”2 She further notes that it was only with the continuation of the Theocritean brand of rustic poetry in Virgil that the genre was cemented.3 Rosenmeyer further notes that the Bucolic entered the modern tradition through “tradition, imitation, continuity of artistic purpose.”4 Bucolic poetry, then, requires reception — the continual rereading and rewriting of its themes and conventions by generations of poets — for its very existence. It is, as Skoie writes, “a matter of piping on pastoral instruments of your forerunners.”5 Theocritus’ first idyll is often read as the introduction to the pastoral genre as a whole, incorporating most of Gutzwiller’s criteria. Rather than two songs in competition, however, the unnamed goatherd offers an extended description of a kissubion, or ivywood cup, which he means to give in exchange for Thyrsis, a herdsman singer’s song. The trope of extended description of an object — or ekphrasis — finds its origin in epic, not bucolic, poetry; however, as essentially “figured reception,”6 it finds an important place in this genre obsessed with its own creation. By the time John Keats writes “Ode On a Grecian Urn” nearly two thousand years later, the ekphrasis is thoroughly integrated into the Bucolic canon. In this paper, I will place these two ekphraseis in conversation, examining their shared and differing themes, as well as the dynamics of viewing and narration built. In both, ekphrasis is used as an allegory of the active creation of the Bucolic genre in which both poets are working. The goatherd’s cup in Theocritus’ first idyll, which he offers in exchange for Thyrsis’ song, is essentially a physical embodiment of the genre’s main themes. The cup itself is κεκλυσμένον ἁδει κηρῶι (“sealed with sweet wax”)7 (27), and ivy, helichryse, and acanthus flowers wind all around it. Its surface holds as much sweetness and simple, natural beauty as does the locus amoenus in which the two interlocutors are sitting that Thyrsis describes for the reader at the outset of the poem. The goatherd also describes three scenes which emerge from between the winding tendrils of the plants: a woman with two competing lovers, an aged fisherman throwing out a net from a craggy rock, and a young boy, whose distracted weaving of a cricket trap leaves the vineyard he is tasked to guard and his lunch open for two mischievous foxes to raid. Rosenmeyer interprets these scenes as “echoes of the world beyond the pleasance” of the pastoral due to their depictions of turmoil and toil which are “frozen” on the cup so as to not overflow into the rest of the poem.8 This description, however, ignores the fact that the toil represented in these scenes is transformed into something altogether Bucolic in the eyes of the goatherd. The theme of frustrated erotic love in the scene of the two young men, for instance, finds its echo both in the story of Daphnis in Thyris’ song and in countless other pastoral idylls, notably the story of Polyphemus and Galatea as told in idylls 6 and 11. The woman laughs (γέλαισα 36) at the men’s labouring in vain, much as Aphrodite laughs (γελάοισα 95) when she witnesses

1 Mathilde Skoie, “Passing on the Panpipes: Genre and Reception.” In Classics and the Uses Reception, ed. Charles Martindale and Richard F. Thomas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 94. 2 Kathryn J. Gutzwiller, A Guide to Hellenistic Literature (Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, 2008), 84. 3 Gutzwiller, A Guide to Hellenistic Literature, 84. 4 Thomas G. Rosenmeyer, The Green Cabinet: Theocritus and the European Pastoral Lyric (Los Angeles and Berkely: University of California Press, 1969), 4. 5 Skoie, “Passing on the Panpipes,” 92. 6 Andrew Bennett, Keats, Narrative and Audience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 135. 7 Unless otherwise stated, all translations are my own. My readings are all greatly informed by the commentary of Richard Hunter in Theocritus: A Selection (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). 8 Rosenmeyer, The Green Cabinet, 91.

Daphnis’ suffering. Further, the men are said to νεικεíουσ' ἐπέεσσι (“strive or quarrel with words”) one after another, which, as Hunter points out, “suggests the Bucolic agon, and ἔπη hints at the performance of hexameters.”9 In other words, the word choice is suggestive of poetic exchange and competition allowing for an interpretation of these men as herdsman singers not unlike Thyrsis. The boy happily weaving an ἀκριδοθήραν — a locust-trap — from asphodel stalks and rush likewise offers an easy analogy to the Bucolic singer, especially when accompanied with the description of the καλὸν [...] ἀλωά (“beautiful vineyard”) weighed down with ripe grapes (46 - 54). Plenty, pleasance, and the joy of creation — or “poetic πóνος,” a reinvention of the traditionally Hesiodic term for labour10 — are the primary focus in this story, despite the imminent threat of losing his lunch, which remains only a minor inconvenience. The aged fisherman is the least obviously Bucolic of the cup’s figures, due to his age and his labouring; however, the focus is in his strength which is ἄξιον ἅβας — worthy of youth (44). He is also, perhaps, proof of the Hesiodic influence on Theocritus’ pastoral: as Rosenmeyer terms it, there is “an echo [...] of πóνoς” in pastoral poetry, though never more.11 Toil can exist in the locus amoenus, but it must only be a flicker of it, or made itself to be pleasant, as the problems of the cup’s figures are. Mostly, it exists outside the frozen, perfect noon-hour in which the poems take place, adding tension and improving the pleasure of the scenes by contrast. The cup captures this perfectly, its figures frozen in states of near-ponos, but so well-made and surrounded by lovely decoration that the goatherd can make pleasant — and thus, pastoralize — their troubles. The thematic programme of Keats’ urn, when placed in comparison to the ivy cup, shares many of its themes, and even some nearly identical images. The poet speaks of a “leaf-fringed legend” which “haunts around [its] shape” (5-6), recalling the ivy and flowers encircling the narratival pictures on the cup. His “Bold Lover,” like the two young men in the cup’s first scene, “never, never canst [...] kiss” (17) and will be “for ever panting” with a “heart high sorrowful and cloyed, / A burning forehead and a parching tongue” (29-30). He, too, is labouring in vain for love. The woman “cannot fade” and will be forever “fair” (19 - 20), which echoes the beautiful woman who is carved on the cup and appears as a τι θεῶν δαíδαλμα — something skillfully made of or by the gods (31). Both women are made near to the immortals by being frozen in art. Keats’ “fair youth” (15) is not weaving but piping, yet his age and placement amongst the perpetual plenty of springtime (“nor ever can those trees be bare” 16) echo the boy in Theocritus, though his affinity with the Bucolic singer is much more explicit. No old man appears on this urn; in fact old age is singled out as inherently separate from the scenes on the urn: in the narrator’s final address to the urn, he says, “When old age doth this generation waste, / Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe / Than ours” (47 - 48). The reminder of aging is still the most direct reference to the suffering of reality outside of the object, as in Theocritus. Similarly to idyll 1, this aging is stopped, the figures frozen into immortality. Thus, the overarching theme and narrative force in both ekphraseis is stillness: the pastoral in both is and must be “cold” in order to achieve “eternity” (45). One scene on Keats’ urn which does not appear to have any parallel in the kissubion is the rather enigmatic passage about the sacrifice; on further examination, this inconsistency further proves the importance of reception to the Bucolic genre. The poet asks the urn: “Who are these coming to the sacrifice? / To what green altar, O mysterious priest, / Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies?” (31-33). While Rosenmeyer argues that “the gods and religion have no standing in the Theocritean bower,”12 he notes that in Virgil’s third Eclogue, Damoetus says that he will make a sacrifice of a heifer for the harvest: faciam vitula pro frugibus.13 Wilson sees the heifer as an echo of the procession scene on the Parthenon frieze (fig. 1), the subject of Keats’ quasi-ekphrastic “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.”14 Therefore, we can interpret this as proof of the eclectic reception that Skoie speaks of.15 From his letters, it is clear that Keats has read Theocritus and

9 Richard Hunter, ed., Theocritus: A Selection (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 80. 10 Niels Koopman, Ancient Greek Ekphrasis: Between Description and Narration (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018), 176. 11 Rosenmeyer, The Green Cabinet, 23. 12 Rosenmeyer, 125. 13 Qtd. in Rosenmeyer, The Green Cabinet, 126. 14 Douglas B. Wilson, “Reading the Urn: Death in Keats’s Arcadia,” Studies in English Literature, 1500 - 1900 25, no. 4 (Autumn 1985): 836. 15 Skoie, “Passing on the Panpipes,” 94.

connects him most strongly to the pastoral tradition, despite not being able to read Greek, as Beatty notes.16 In 1818, the poet writes to his brother that when inspiration strikes him, he is “according to [his] state of mind, [...] with Achilles shouting in the Trenches, or with Theocritus in the Vales of Sicily.”17 This letter proves what his poem already implies: his pastoral style comes from a variety of sources. Even the inclusion of Achilles, the epic hero, does not seem out of place in his list of possible inspirations. The motif of ekphrasis, as I mentioned above, stems famously from the Shield of Achilles in Homer; an element of epic is the key motif of both Keats’ poem and the ivy-cup of Theocritus’ goatherd. In Theocritus, not only is the ekphrastic mode Homeric, the kissubion itself also finds poetic precedent in Homer — both the herdsman Eumaeus and Polyphemus — himself a sort of shepherd — drink out of a similar ivy-cup.18 The implication, then, is that this is a cup for rustic people, but the actual allusion is to epic poetry. Further, Theocritus’ lovers do not simply quarrel but νεικείουσ' ἐπέεσσι (strive with words), which Hunter notes “rewrites the ‘legal’ νεῖκος of the Homeric shield.”19 The old fisherman, like Keats’ cow, might also have a source in real art: Hunter claims that “‘realistic’ depiction of veins, muscles, and sinews is a familiar feature of Hellenistic statuary,”20 such as, most famously, the Louvre Fisherman (fig. 2). Thus, Theocritus’ preoccupation with the fisherman’s rough physicality can be read as his appeal to the visual arts as a source for poetry. All these glimpses of other sources, unexplained by the dialogue between our two poems, open up the possibility to trace countless other conversations that the poets are engaging with other poetic traditions and even other media in order to create their embodiment of the pastoral. Though some aspects — nature, song, pleasance — seem necessary for any poem to be read as Bucolic, the actual content and sources seem less important than the way in which they are told. It is thus the narrative structure of both these ekphraseis which I will attend to next. In both Keats’ and Theocritus’ descriptions of their objects, a narrator describes and interprets them for the reader, but there are key differences in the framing of this narrative which allow us to explore how these ekphraseis mirror our poets’ act of genre creation or innovation through reception. In idyll 1, the description has a role in the poem’s larger narrative, as the goatherd is describing it for Thyrsis, to whom he means to give the cup in return for a song. Thus, Halperin notes that “according to rustic notions of value, the song is equivalent to the cup in value.”21 This idea is also echoed through the goatherd’s conditional offer αἰ δέ κ ' αεíσῃς [...] αἶγά τέ τοι δωσῶ [...] βαθὺ κισσύβιον (“And if you should sing, [...] I will give to you both a goat and a deep ivy-cup”) (23 - 27), the use of the indicative future form of δωσῶ proving the direct correlation: provided Thyris sings, the goatherd will hand over the cup. The “performance of the cup” through ekphrastic description can thus be read as one half of a competitive song exchange.22 The term performance seems appropriate in this situation: as Payne points out, the cup is never actually produced, nor is Thyrsis invited to look at it until after his song is finished.23 The description is therefore an act of poetic creation, wherein the goatherd is conjuring the image up in both Thyris’ and the reader’s minds. Further, he describes more than could possibly be visible on the cup. The narrator seems able to easily read and interpret the minds of the characters. He claims to know that the men are suffering from love as the woman’s νοός — her mind and, by extension, attention — is being tossed carelessly between them; that the foxes intend to go after the boy’s food and vines while the boy himself is happily devoting all his attention to his weaving. In addition, the figures appear to be in motion, the scenes all too dynamic to be truly carved into a wooden cup. The unnamed goatherd is also able to predict what the viewer’s reactions will be: of the fisherman, he claims φαίης κεν γυίων νιν ὅσον σθένος ἐλλοπιεύειν (“You would say that he is fishing with all the strength of his limbs”) (42); at the end of his description, he says the cup is τέρας κε τυ θυμὸν ἀτύξαι (“A wonder; it would amaze your heart”) (56). The second person ‘τυ,’ literally directed to Thyrsis but also in

16 Frederika Beatty, “Theocritus in Hampstead,” The Classical Journal 43, no 6 (March 1948): 328 17 Qtd. in Beatty, “Theocritus in Hampstead,” 327. 18 David M. Halperin, “Three Scenes on an Ivy-Cup,” in Before Pastoral: Theocritus and the Ancient Tradition of Bucolic Poetry (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983), 168. 19 Hunter, ed., Theocritus: A Selection, 80. 20 Hunter, ed., 82. 21 Halperin, “Three Scenes on an Ivy-Cup,” 163. 22 Vassiliki Frangeskou, “Theocritus’ ‘Idyll’ 1: an unusual Bucolic Agon.” Hermathena 161 (Winter 1996): 25 23 Mark Payne, “Ecphrasis and song in Theocritus’ Idyll 1,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 42, (2001): 265.

and object is necessary to the creation of the artwork itself; further, by preempting the viewer’s own reception of the work, it mirrors the ongoing reading and rereading of the work, thus actively engaging in the creation of its own genre. The conclusion of each ekphrasis, as the moment when the narrator’s guidance ends and the poem is passed over to the memory of the reader, are key to understanding the allegory of genre creation. The final couplet of Ode on a Grecian Urn is accepted as the poem’s ultimate thesis. Precious little else about these two lines has any degree of scholarly consensus. The punctuation, it seems, is the sticking point, sparking strikingly similar debates to those over the corrupt lines of Theocritus. O’Rourke notes that the lines appear in the latest manuscript from Keats’ lifetime as follows:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” — that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.28

With this punctuation, the urn breaks its long-held silence to speak just five words, and the rest is the response of the poet. The silent urn is made to speak, as “a friend to man, to whom [it] says” the above, even after “old age shall this generation waste” (46-48). Eternal, it speaks to all men, through all time. The meaning, at first, supports a reading of a Romantic assertion of what the pastoral means: a celebration of simple beauty, along the lines of Schiller’s treatise on “Naive and Sentimental Poetry”29 — the urn is perhaps asserting the value of the natural, simple lives which play out on its surface. The preoccupation with artistic creation and the complexities of its dynamics of viewing, however, negate this simplified vision of the pastoral. The urn only exists through Keats’ artistic creation, rather than nature. The final couplet is thus an assertion of the pastoral genre’s power to create something which does not exist. Further, his art has the ability to speak to the world at large. This speech is the extension of the Bucolic genre out of the locus amoenus and into the minds of every single one of the poem’s readers. Keats’ poem, then, ends with the claim of the Bucolic genre’s continuation through the reception of its continued reader. In contrast, Theocritus’ poem has no such declaration, merely a hand off of the cup from the goatherd to Thyrsis. The goatherd invites the singer to examine the cup for himself, saying, ἠνíδε τοι τò δέπας· θᾶσαι, φíλος, ὡς καλòν ὄσδει (“Here is the cup for you; admire, friend, how sweet it smells”) (149). The cup is now made manifest, just as Keats’ urn is made real enough to speak by the end of his poem. The goatherd also adds that Ὡρᾶν πεπλύσθαι νιν ἐπὶ κράναισι δοκησεῖς (“You would think it to be washed in the streams of the Hours”) (150), once again directing the reader’s impression of the cup, as well as adding to the cup’s narrative. The “Hours” are, as Hunter points out, associated with the Graces; the cup’s connection to these goddesses of beauty and creativity confers poetic power on it and the genre it represents.30 Further, the introduction of the water motif immediately after the story of Daphnis — which ends with its hero dissolving into a stream — also shows the process through which the genre will continue: this is the first moment of reception, as Thyrsis’ song adds to and changes the character of the cup. This scene aligns with Skoie’s idea of the Bucolic existing in this sort of passing down or at the meeting of two poets.31 Leaving the kissubion in Thyrsis’ hands, Theocritus foreshadows the continued handing down of the cup through countless other poets, and thus, the continuation of the creation of Bucolic poetry. Thus, the presentation of pastoral themes through the poet’s narrative manipulation in the ivy-cup and the Grecian urn allegorizes the Bucolic genre in which the poets are participating. The dialogue between poet and object, as well as between the poems themselves, are necessary to the formation of the genre. Both the urn and the goatherd’s cup appear in their poems as simultaneously and paradoxically concrete and entirely abstract. When reading these two poems, the reader must simultaneously believe in their existence in space in order to follow Keats and Theocritus’ careful tracing of ivy and flowers, maidens and men across their surface, but also accept that they could never exist in the way that they are described. They can exist only through imagination. Bucolic poetry itself is much the same. The heavy heat and slow time of the noon-hour,

28 Qtd in. O’Rourke, “Persona and Voice,” 27. 29 Friedrich Schiller, Naive and Sentimental Poetry and On the Sublime, translated by Julius A. Elias (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company, 1966). 30 Hunter, ed., Theocritus: A Selection, 106. 31 Skoie, “Passing on the Panpipes,” 92.

practice referring to the reader, combined with the the potential particles κεν and κε, contributes to the sense that the goatherd is creating the cup in your mind, but that the cup is not truly a physical object accessible to either you the reader or the you in the poem, ie. Thyrsis. It is the goatherd’s — and thus, the poet’s — ability to craft a poetic description of the ivy-cup that is truly striking the reader as a wonder. Meanwhile, in Keats’ poem, the narrator’s interlocutor is the urn itself. This one-sided dialogue encompasses the entire poem, without a narrative frame. The first stanza illustrates perfectly this style of narration. Before launching into any description of the urn itself, Keats addresses it directly:

Thou still unravished bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? (1-7)

He follows this description by six more unanswered questions in rapid succession, creating a sense of a frantic interrogation, before repeating again the power of silence:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endeared, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone. (11-14)

These passages quite obviously entrench the poem within a distinctly Bucolic tradition from the outset and once again point to the variety of sources for this genre — recalling both Tempe and Arcady alone nods to Theocritus and Virgil in the space of one line. What is most important, though, is the duality of silence and sound. The quietness of the urn is said to make its story “sweeter,” which is reiterated again in the following stanza’s claim for “unheard” melodies. This, at first glance, seems to engage in a paragone of art and poetry, popular in literary and artistic circles at least since the Renaissance, and which is traditionally associated with ekphrastic poetry, according to Hagstrum.24 In this tradition, some version of Horace’s maxim ut pictura poesis — as in painting, so in poetry — or Simonides’ characterization of poetry as a speaking picture is used to elevate either poetry or painting to the level of the other, depending on the current relative cultural value of the two media.25 O’Rourke finds this explanation wanting, as the power of such a “historical theme [...] over a particular literary text” is impossible to judge.26 While the assertion of poetry’s power is one aspect, Bennett’s characterization of ekphrasis in this ode as “figured reception,” reveals that it goes beyond that: the poem is a “production (partly by mimesis) of our response to the text as a work of art.”27 Rather than speaking authoritatively to a viewer in the second person as in idyll 1, in Keat’s poem, the narrator’s reactions to the urn serve to reflect what the viewer’s should be to the poem, which is the true artwork. The urn, like the kissubion, only exists in its description. Further, the scenes it depicts seem to move and change: their figures too dynamic and too life-like, the descriptions of sounds and feelings altogether too sensual for the “unravished bride of quietness” it is said to be. The poet’s insistent repetitions regarding the urn’s quiet stillness seem only to emphasize that, in the hands of the poet, as in the mouth of Theocritus’ goatherd, the object is neither quiet nor still. Both narrators’ accomplishment is to make apparent what is not visible and make alive what is carved in wood or painted on marble; in short, to create what can never exist. Both poems use pictorial description in order to model their own reception. The dialogue between narrator

24 Jean Hagstrum, The Sister Arts, The Tradition of Literary Pictorialism and English Poetry from Dryden to Gray (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1958), 24 - 28. 25 Hagstrum, The Sister Arts, 24 - 28. 26 James O’Rourke, “Persona and Voice in the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn,’” Studies in Romanticism 26, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 31. 27 Bennett, Keats, Narrative and Audience, 135.

APPENDIX

Fig. 1: Marble Relief from the South frieze of the Parthenon, 438-432 BCE, marble, British Museum.

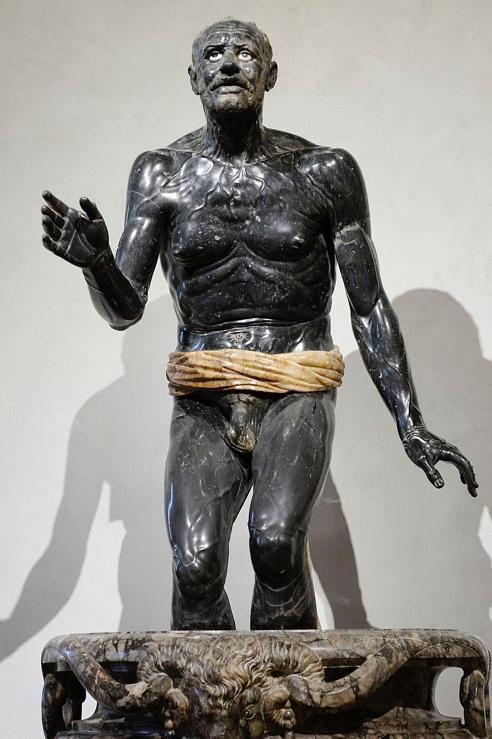

Fig. 2: The Old Fisherman Vatican-Louvre, 2nd century BCE Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, black marble and alabaster, 1.8m, Musée du Louvre.

the whispering of the trees and brooks, the piping and singing of the rustic but somehow educated singers — all of these jump from the page into the readers’ mind’s eye, fanciful but vibrant and vital. The power of the Pastoral, then, is nearly a shared vision — or pleasant delusion — which passes from poet to poet and reader to reader through millenia. It is this power which transforms the urn, the cup, and the ink on the page — the “Cold Pastoral” — to the eternal, elusive beauty which the poetry evokes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Bennett, Andrew. Keats, Narrative and Audience: The Posthumous Life of Writing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994. Beatty, Frederika. “Theocritus in Hampstead.” The Classical Journal 43, no. 6 (March 1948): 327 - 332. Frangeskou, Vassiliki. “Theocritus’ ‘Idyll’ 1: an unusual Bucolic Agon.” Hermathena 161 (Winter 1996): 23 - 42. Gutzwiller, Kathryn J. A Guide to Hellenistic Literature. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, 2008. Hagstrum, Jean H. The Sister Arts, The Tradition of Literary Pictorialism and English Poetry from Dryden to Gray. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1958. Halperin, David M. “Three Scenes on an Ivy-Cup.” In Before Pastoral: Theocritus and the Ancient Tradition of Bucolic Poetry, 161 - 190. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983. Keats, John. “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” In Selected Poems, edited by John Barnard, 191-92. London: Penguin Classics, 2007. Koopman, Niels. Ancient Greek Ekphrasis: Between Description and Narration. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1163/9789004375130_006. O’Rourke, James. “Persona and Voice in the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn.’” Studies in Romanticism 26, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 27- 48. Payne, Mark. “Ecphrasis and song in Theocritus’ Idyll 1.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 42 (2001): 263 - 87. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. The Green Cabinet: Theocritus and the European Pastoral Lyric. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969. Schiller, Friedrich. Naive and Sentimental Poetry and On the Sublime. Translated by Julius A. Elias. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company, 1966. Skoie, Mathilde. “Passing on the Panpipes: Genre and Reception.” In Classics and the Uses Reception, edited by Charles Martindale and Richard F. Thomas, 92-103. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006. Theocritus. A Selection: Idylls, edited by Richard Hunter. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Wilson, Douglas B. “Reading the Urn: Death in Keats’s Arcadia.” Studies in English Literature, 1500 - 1900 25, no. 4 (Autumn 1985): 823 - 844.