16 minute read

From homesteader to conservationist: the evolution of Enos Mills

Editor’s note: Enos Mills is considered the father of Rocky Mountain National Park, which was officially established by the US government as the nation’s third national park on January 26, 1915. We are honored to have his great-granddaughter, who along with her mother, runs the Enos Mills Cabin operating out of Enos Mills' original homestead cabin, write this original piece for us in celebration of Rocky’s 106 birthday this month.

By Eryn V. Mills

Advertisement

As a boy, Enos Abijah Mills, was the ninth child out of eleven of Enos and Ann Mills. Enos Sr. and Ann were of hearty Quaker stock, and moved from Indiana to Pleasanton, Kansas. They “came for the avowed purpose of helping to make Kansas a free state” in 1857, four years before the Civil War began.

A brief time in Breckenridge in 1860 to try mining was formative and adventurous for them, but they returned to Pleasanton, Kansas, to farm wheat and raise their family. Enos was born April 22, 1870. Pleasanton is in the southeast corner of Linn County, Kansas, near the Missouri border. Out of the Mills family brood of eleven, only seven survived past the age of two years. Enos Sr. was easily six feet tall, and Ann was about four foot-ten or so.

Ann became a Quaker preacher at the age of 83, and outlived her husband and all but her two youngest sons, Horace and Joe. More information on the genealogy can be found on our website.

During Enos' childhood and early teens, his family called him Tom. His youngest brother, Enoch, went by the name of Joe. I imagine these nicknames happened early on to avoid confusion. For the purposes of clarity, I'll be referring to Enos Abijah simply as Enos. Joe (Enoch) kept his nickname the rest of his life.

Enos was always a small, sickly child. He was bright, intuitive, hard-working when he could, and studious. There was a school in Pleasanton which he did attend occasionally when his health allowed. His elder sisters tutored him to keep him up on his schoolwork when he was unable to attend. His parents often borrowed books from anywhere they could in order to encourage all their children in their studies. His sisters were particularly sharp.

Enos Mills. Sr. and Ann Lamb Mills, Enos’ parents, were of hearty Quaker stock.

Photo courtesy of Enos Mills Cabin.

One of them married a teacher who was able to eventually tutor Enos through the eighth grade, certificates and all. The copious books in the house also made Enos a voracious reader. He would often help with the household chores, during which Ann would tell him stories of her me in Breckenridge.

These stories fascinated him, and he dreamt of traveling to Colorado. Unfortunately, Enos' health did not improve on the farm. He was thin and weak, and often unable to help with the more strenuous chores. His parents were rightly concerned about him. When he was about thirteen years old, the local doctor tried in vain to diagnose his illness, and in what was most likely a hushed conversation, the doctor said that Enos might not live another six months. Something had to be done.

Let's be clear, Enos' parents loved him. They wanted him to thrive and survive. Enos, with both ears full of stories of Colorado, set out for our fair state with Enos Sr.'s and Ann's blessing, hoping that he would return.

The Big Thompson River as it looked when Enos Mills first laid eyes on Estes Park.

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin.

They hoped the rarified air of Colorado would do much for his health, as they had themselves experienced. Enos, at the tender age of 14, hitch-hiked to Kansas City, which fortunately wasn't far, and got a job at a bakery to earn enough money for a train ticket to Denver.

From Denver he went to Greeley, where his sister, Belle, lived with her husband (the teacher who had certified him through the eighth grade). He then came to Estes Park in 1884, but this was not a random choice. His cousins, the Reverend Elkanah Lamb, his wife Ruth, and their son, Carlyle, had homesteaded in what would become known as Tahosa Valley.

The Lambs had homesteaded in 1871 at what is now known as Wind River Ranch, and then in 1874 they moved to a lower spot in the valley where Longs Peak Inn (and now the Salvation Army) is located.

The Lambs owned the Longs Peak House. It was both a guest house and a jumping-off place for people who wanted to climb the peak or just pass through. Both Elkanah and Carlyle guided guests up the peak, and Carlyle guided Enos on his first trip up Longs in 1885 with some other guests. Enos became smitten with the peak. From then on, he wanted to guide on Longs Peak.

Eventually, Enos would know Longs Peak in every sort of weather, every season, and every time of day. In 1903 he was the first person to descend the East Face in January. Granted, he rather tumbled the last few hundred feet after starting an avalanche, but he survived.

Enos Mills’ (far right, at 15) first climb up Longs Peak, in 1885.

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin.

Across the stream to the east from the Longs Peak House was a plot of land that had yet to be claimed, and Enos thought it would be the perfect place for a homestead. It was 1885, and he was fifteen years old. Building a cabin proved to be a challenge, as it took him two summers to complete.

The first summer, he put up the walls, made of rough-hewn logs, and the second summer he erected the roof, slightly delayed by bluebirds nesting on the top rafter. Sleeping out under the stars did not bother him in the slightest. He was in love with the cool nights and the temperate days, and the abundance of wildlife that surrounded him.

The cabin itself was rather modern. He was able to purchase a set of windows (one pane of which is still intact), a small wood-burning stove, corrugated tin roofing, and eventually thick insulation paper for the interior. He had a desk and chair by the window, fashioned trunks for himself from produce crates, and from nearby sawmills was able to obtain floorboards and roofboards.

The money Enos earned from odd jobs around the Estes Park area, and his job at Elkhorn Lodge, made his homestead a cozy bachelor cabin, with a view of Longs Peak to boot. While he did spend a few winters at his homestead later in life, it was mostly occupied in the summers, and even then, he was often on a hike or traveling.

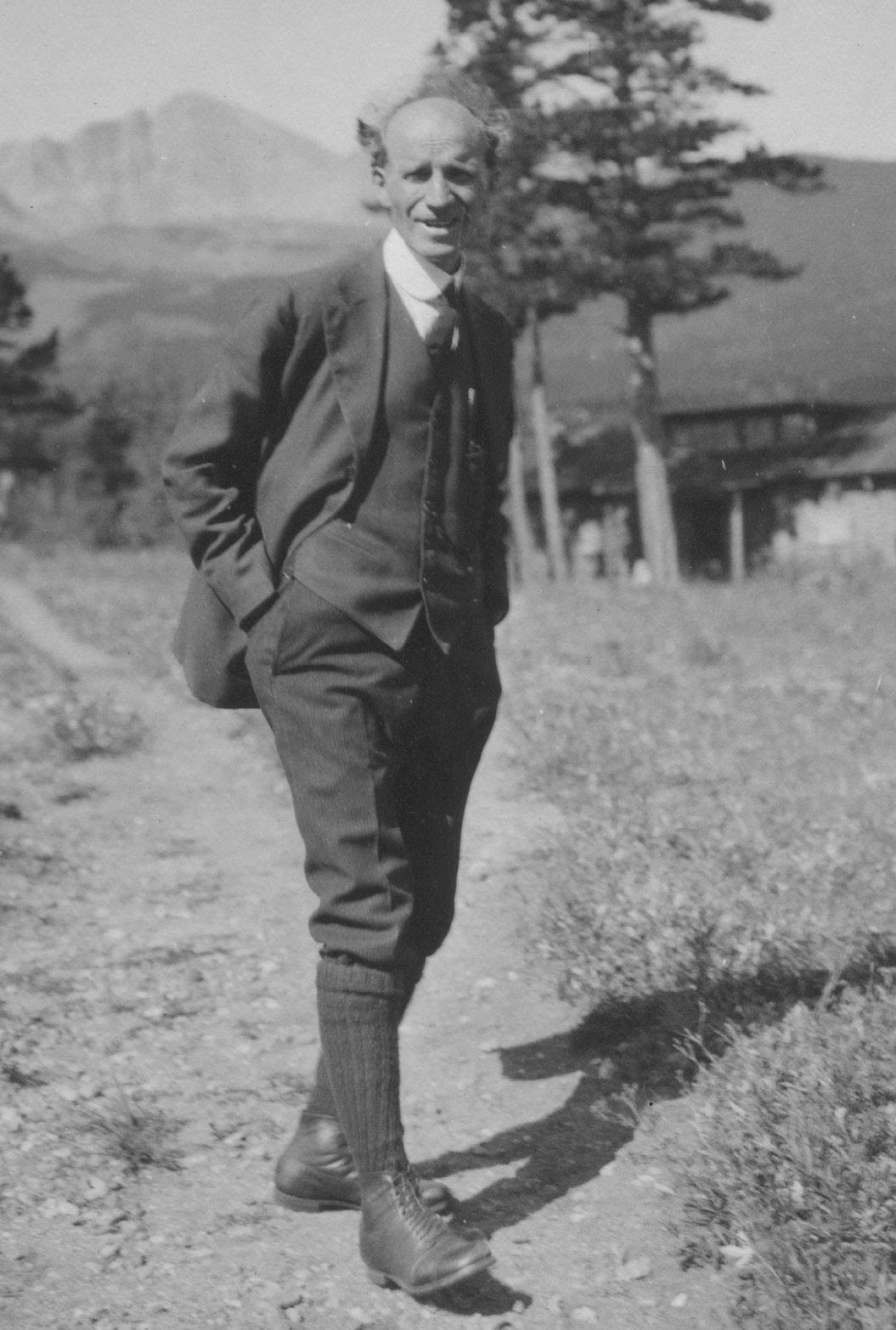

Enos Mills at 16 near his homestead in the Tahosa Valley.

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin.

Even though Estes Park was populated during summer, opportunities dried up during winters, and Enos, who did not hunt, trap, or fish for a living, still needed to make some income.

Between 1887 and 1901, he worked at the Anaconda Copper Mine in Butte, Montana. While in Butte, Enos learned a great deal about mining, though he very rarely wrote about it. Butte, though, was a bustling mining city with every walk of life, and it had an excellent library which he wasted no time in exploring. It was the first place he visited upon his arrival.

It was also here where he learned his mysterious childhood illness was actually an allergy to wheat, as the Butte doctor was fresh from New York and had learned about this new idea called “allergies."

Enos' parents owned a wheat farm and broke bread at the beginning of every meal. But it turned out Enos was allergic to wheat. After ten days of fasting and then watching carefully what he ate, he was a cured young man at the age of seventeen.

At the Anaconda Copper Mine, he began as a “nipper”, or tool-boy. He ran drill bits from one end of the mine to the other, but he was inquisitive and energetic. By the time he left thirteen winters later, he was a certified stationary engineer. To this day I have only the slightest inkling of what that means. Enos' time in Butte is hardly referenced in his writings. He worked through the winter and returned to his homestead in the summer, where the wilderness sustained his fascinations.

Enos' time in Butte gave him a modicum of extra cash, and being a single young man, he traveled. A literary education could only provide him so much, so he explored. By the time he was thirty years old, he claimed he made a campfire in every state and territory in the Union including Alaska, Europe, and parts of Mexico and Canada. One particular trip in his youth stood out.

In 1888, when he was eighteen years old, the Anaconda Copper Mine owners saw fit to send him to business school in San Francisco. Enos tried it, but it didn't take. One day, he wandered along the shorelines of San Francisco Bay.

He picked up a piece of kelp, and knowing little about it, he approached the next person on the beach who looked somewhat local. As they talked, this stranger seemed to match Enos' interests in the natural world. This man turned out to be John Muir. Muir found a kindred spirit in young Enos, and took him under his wing. He encouraged Enos to pursue his ravenous interest in nature, and join the cause of conservation.

Muir also encouraged Enos to use all of his talents to pique interest in those he met of the study of nature. Enos took Muir's advice and ran with it at full sprint.

Over the course of his life, Enos gave countless speeches, wrote articles and books, and sold his photography to railroad companies to help advertise the natural world. It took a number of years for Enos to learn his craft, but he was always on the move, and always learning. Enos and John Muir remained friends until Muir's death in 1914.

Enos Mills as an adult

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin

Enos never knew a fear of the wilderness. He also never carried a gun of any kind. He did occasionally travel with people who did, but he found it a most distracting experience. He was never attacked by a wild animal. He did attack a coyote once, and he scared off a mountain lion. Both of these stories can be found in his books, but I shall let you find these out on your own.

For all his time in the wilderness, the most lethal weapon he carried was a hatchet. He carried raisins, peanuts, and chocolate as snack food, however, the wilderness has food as long as one knows how to find it.

Being a farm kid, he did. (Please be aware: do not pick plants or mushrooms you do not know about.) In Enos' day, one could drink straight from the mountain streams, but we do not recommend that today.

In 1901, Enos bought the Lamb's Ranch from Carlyle Lamb, and in 1904 he changed its name to Longs Peak Inn.

Longs Peak Inn. renamed as such in 1904, at the base of Longs Peak

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin

Sitting at the base of Longs Peak, it was perfectly situated for his guided climbs up Longs Peak, and to house travelers who, if they didn't want to climb, could enjoy the Rocky Mountain area, with or without a guide.

This is where Enos began to train his nature guides. Enos preferred small groups for the trips up Longs Peak, no larger than six, as it allowed him and his guides to make sure that everyone returned to the inn safely. During Enos time guiding on Longs Peak, no one was lost and no one died.

Longs Peak Inn was a unique hotel in that Enos did not allow music, drinking, smoking, or card-playing in the lobby. (What one did it one's own room was their business.) He wasn't particularly against those things - he had a Victrola, as did his staff - but he believed that if a guest had traveled halfway across the country to visit a place as sublime as Longs Peak, why spend it on the patio?

Those with an adventurous spirit flocked to Longs Peak Inn in greater numbers every year.

Longs Peak Inn usually shut down in the autumn and reopened the following June. In the meantime, Enos worked other jobs more suited to his talents.

In 1903, Enos became the first “Colorado Snow Observer," recruited by a friend of his from Telluride, Colorado.

Enos either skied or snowshoed into the heights and measured the snowpack over the winter, reporting back to the USDA of his measurements so the farmers down below knew what to expect come spring. No one else was willing to do this at the time.

In 1906, he was appointed the National Lecturer on Forestry, paid by the United States Government to speak specifically on the interests of forestry. This gave him an in-road for the path he would take later.

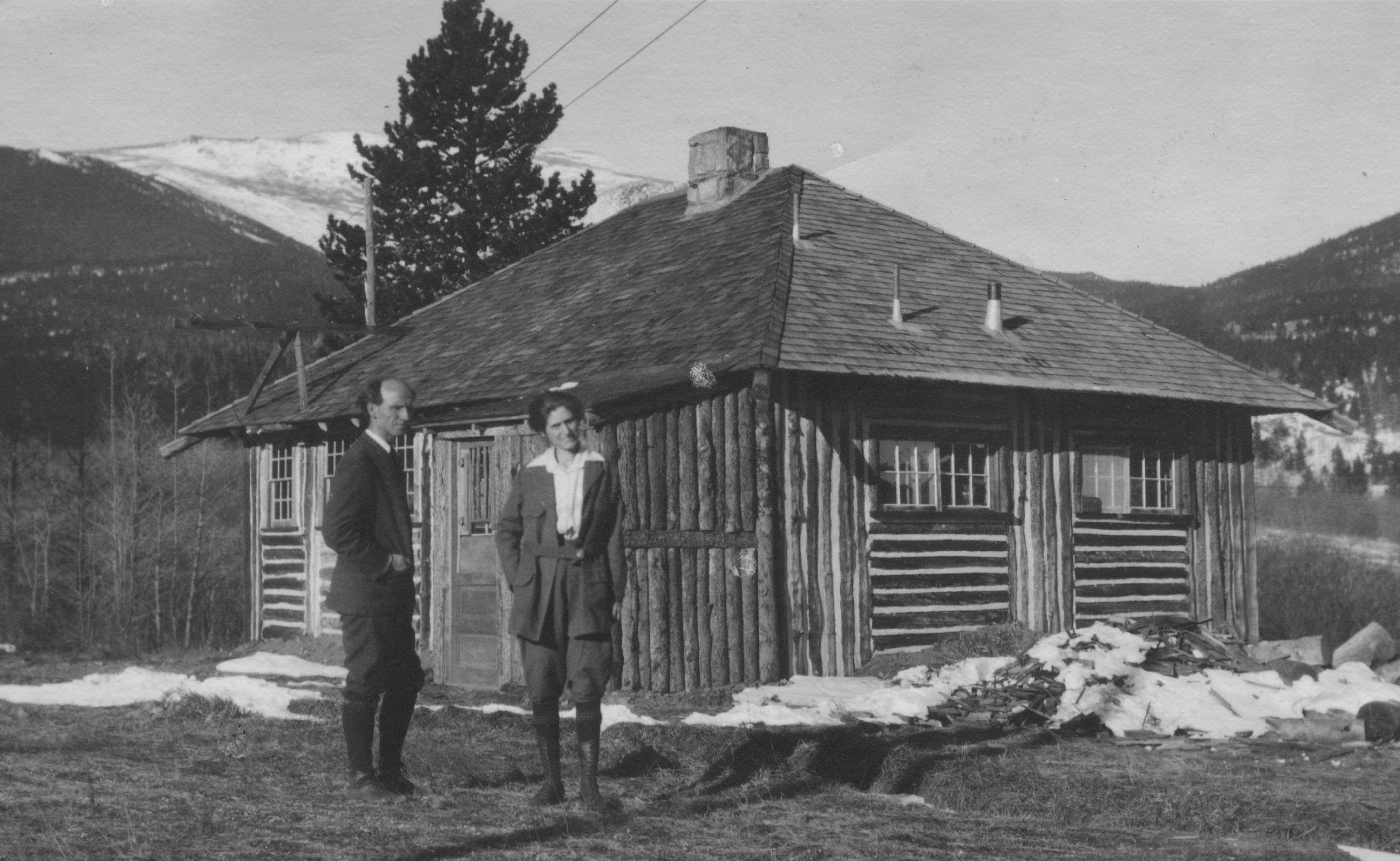

Enos and Esther Mills at his homestead cabin in the Tahosa Valley.

Photo courtesy of Enos Mills Cabin.

Some of his theories and practices on what he called “nature guiding” are still taught today in interpretation classes in colleges around the country.

In June of 1906, the main building of the Longs Peak Inn was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Enos raced back from St. Paul, Minnesota, where he had been giving a speech, and immediately began to rebuild it.

A forest fire in 1900 had left a swath of dead standing trees on the slopes of Longs Peak, and Enos took the opportunity to rebuild his lodge out of those, rather than cutting down perfectly good living trees.

By July 4th of the same year, the kitchen and dining room of the new Longs Peak Inn was ready to serve guests. From that point on every summer there were improvements to be made, with the forest as his architect.

The Longs Peak Inn and its various outbuildings were organic structures. Eventually, Longs Peak Inn had feather beds, steam heat, electric lights, and three telephones on the property.

The kitchen was kept with wood-burning stoves, and the dining room was a "no-tip" house. This was a practice Enos picked up in Europe. He believed in paying staff well enough that they would not need tips. Longs Peak Inn became such a draw by 1915 that it was rated one of the top three places to stay in Colorado along with the Broadmoor in Colorado Springs, and the Brown Palace in Denver.

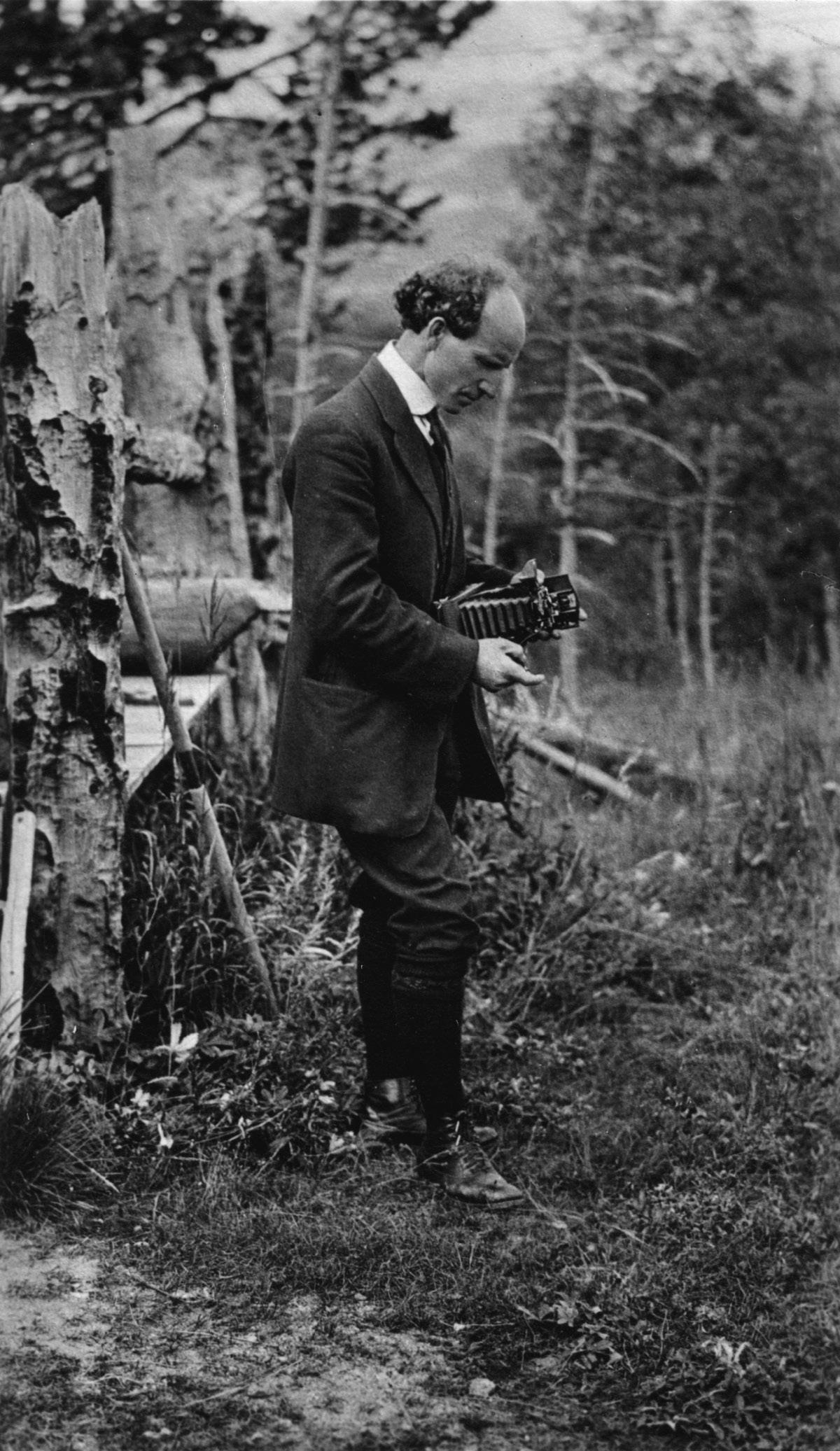

Enos Mills and his Eastman Kodak Pocket Camera.

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin

In 1907, his first book, “Wild Life on the Rockies”, truly launched him into the public eye. From that point on, he managed to produce a book on nature every two years. They usually had a theme, and generally he had several books in various draft stages in his office.

They began as magazine articles, and would be organized to whatever theme he sought fit for them. Enos' books were illustrated with his own photographs, a great many of them taken with an Eastman Kodak Pocket Camera.

In 1909, Enos moved from his homestead cabin to new cabin built at Longs Peak in for his purposes. For a while, he called it his “work room”. This was the year he began to work on the creation of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Enos became a member of the Estes Park Protective and Improvement Association in 1907. Tourists were destructively running rampant over the Estes Valley, and business owners, including Enos, decided it was time to make a change.

Enos made the suggestion of campaigning for a national park near the area and most of the hotel owners thought it was a great idea, including F.O. Stanley. Enos and the others in the club thought it would be best if Enos was the mouthpiece for the effort.

What is not widely known is that F. O. Stanley financially backed Enos. During summers, Enos ran Longs Peak Inn. The moment he could be on the road, he was.

Charles Edwin Hewes, Enos Mills, and FO Stanley were all members of the Estes Park Protective and Improvement Association.

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin

For six years, Enos spoke, wrote, lobbied, sold photographs, and did whatever else he could to further the cause of Rocky Mountain National Park and other city, state and national parks across the country.

Every state had a beauty spot that needed to be persevered, he believed. He traveled so widely and was so prolific in his writings, that he became acquainted with Eugene Debs, Edna Ferber, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., Helen Keller, Lowell Thomas, Ernest Thomson Seton, Charles Evans Hughes, J. Horace McFarland, Mary Belle King Sherman (Colorado Chair of the General Federation of Womens' Clubs Conservation Department), and Presidents William Taft, Woodrow Wilson, and Teddy Roosevelt.

His experience as a miner in his youth, and his years in the wilderness gave his speeches and articles a balanced perspective on conservation and a growing population's need for natural resources. He was able to appeal to businessmen and public organizations all over the nation.

The front page of the Denver Post on January 20, 1915, six days prior to Rocky Mountain National Park being signed into law by Congress.

RMNP photo

Rocky Mountain National Park was created by an Act of Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on January 26, 1915. The Denver Post dubbed Enos A. Mills the “Father of Rocky Mountain National Park." He was the keynote speaker at the Park's official opening in September, 1915.

Enos did eventually marry. Esther Burnell, an interior decorator from Cleveland, came to Estes Park in 1916 for a vacation, but decided to stay and homestead. She homesteaded four miles west of Estes Park.

In the spring of 1917, after a long month of snow, she decided to visit friends in Grand Lake. She put on her snowshoes and made a moonlit hike over the Continental Divide. Esther made it there in one night.

Esther and Enda (my grandmother) Mills having lunch on the trail.

Photo courtesy of Enos Mills Cabin.

Enos was impressed with this feat, and began courting her. She became his personal secretary in the summer of 1917. When her sister, Elizabeth Burnell, who had an equal enthusiasm for the natural world, visited for the summer, they became nature guides at Longs Peak Inn.

Esther was the first licensed Nature Guide with the National Park Service, and Elizabeth was the second. The National Park Service now calls this the Field of Interpretation.

Enos and Enda Mills

Photo courtesy of the Enos Mills Cabin

In August of 1918, Enos and Esther were married in the doorway of his homestead across the road from Longs Peak Inn. They did not reside there, however. Enos had been living at Longs Peak Inn since 1909 and the Inn was well suited for their growing family.

Their daughter, Enda, was born April 27, 1919, and Enos couldn't have been happier.

Enos continued to write, speak, and travel, however, as matters of conservation elsewhere in the nation begged his attention. He spent as much time as he could with his family.

Enos died in September of 1922. A litany of factors led to his death. Ultimately, he died from septicemia, or blood poisoning, from an abscessed tooth.

Esther, widowed after only four years of marriage, had him cremated. She spread his ashes secretly, and kept the secret to her own death. Esther Burnell Mills died in 1964, she never remarried. She sold Longs Peak Inn in 1946, and in June of 1949 the main building of Longs Peak Inn burned down.

Twisted pine with Longs Peak in the background.

Photo courtesy of Enos Mills Cabin.

Fortunately, Enos leaves behind a legacy of books, photographs, a proud profession of interpreters in the National Park Service, and Rocky Mountain National Park itself, which still inspires millions of people each year.

Eryn V. Mills is the great-granddaughter of Enos A. Mills, who is widely regarded as “The Father of Rocky Mountain National Park”. She and her mother, Elizabeth Mills, own the Enos Mills Cabin, a museum dedicated to his memory located on his homestead property. More information can be found at www.enosmills.com