19 minute read

The Old Girls’ Club

The Old Girls’ Club continue to actively engage in all aspects of the school community.

Our thriving Thrift Shop is settling into its new premises located beneath the pillars. This central location has provided increased space, visibility and easy access. Most recently the shop has started to record its carbon offset by weighing the items sold. The school community has seen the benefit of providing a sustainable approach and reducing items that are sent to landfill.

The items sold, along with other fundraising activities, help raise valuable funds that go back to the school. This year we are supporting a wide range of initiatives including:

• the purchase of equipment to encourage entrepreneurial activity across the community

• supporting co-curricular clubs

• currently looking at funding break out areas for pupils to encourage time to reflect, relax and reset

The committee members love nothing more than getting to see the pupils excel and this summer many of us enjoyed the opportunity to sell refreshments and strawberries at the summer extravaganza, We Will Rock You. The nights passed so quickly with the fabulous entertainment and family atmosphere. We can’t wait to get involved in the next whole community event, watch this space!

The committee of volunteers is actively seeking new members to take the club into the next phase. We are in discussions with the school to help support, physically and financially, a range of events in the forthcoming year. We would love to hear from Old Girls who could volunteer at these events and/or join the committee. We meet four times per year at Mayfield. If you are full of great ideas, like to support pupils in achieving success and have a creative team spirit we would love to hear from you.

Ashley Petrie (President – High School of Dundee Old Girls’ Club)

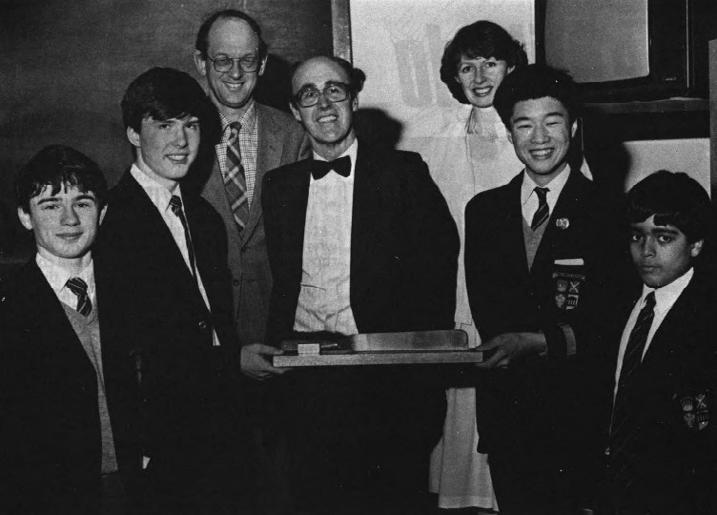

Sending Spartans to Hong Kong

The Agoge was a special school dedicated to turning Spartan boys into fearsome fighters. At age 12 and given nothing but a spear and blanket they were sent into the wilderness for a month to fend for themselves. Most did not make it, returning cold, hungry and broken after a week. Those who survived were welcomed back as men.

Today the human tendency to test and challenge remains undimmed and many desire to test their children, to push them to their limits, to see what happens. Often referred to as ‘tough love.’

Yusuf Okhai is compelling company. A tsunami of selfdeprecating humour and infectious laughter that puts others at ease but does not hide a ferocious ‘always on’ intellect. For most short magazine pieces an interview of 60 mins is enough, longer creates unnecessary editing issues and leaves most of the copy on the cutting room floor. But occasionally you forget where you are and just enjoy listening, with Yusuf two and a half hours passed in a flash.

I never had a plan. I had a job at Ernst and Young and then there was an offer from dad to go into the family business and start up a new factory. He said ‘run a factory’ he meant ‘come and build a factory’ which wasn’t the same thing at all. So, I went to the office and they didn’t even tell me what was going on. I asked him [dad] what I was meant to be doing and he kicked me out of the office and said ‘nothing’. So, I helped in the general office and after a few weeks he said ‘come I’ll show you where the factory is going to be’. It was an empty warehouse with holes in it. I was given a bunch of Brillo pads and pointed in the direction of the ‘new’ scrap, an ice pole machine, once cleaned it was going in the factory. That first factory was horrible but probably a good grounding, tough love – teaching people through fire.

I was there for six years, working as a grease monkey. [A selfdeprecating laugh at the memory]. It changed from an ice pole factory to a bottle factory but a fire meant our customers found other suppliers, so we had to fill the bottles we had with juice, except we were nearly bankrupt. I was given a bunch of ‘unrepairable’ machines from a scrap yard and told to fix them. But I am not any type of engineer, so I am given a couple of aircraft engineers! Factory engineers are rare, aircraft ones less so. It was horrible, aircraft engineering is very, very regulated, everything needs a tick box. I didn’t know about days off for greasing and what not – I just switch it on and smashed out the goods. The guys didn’t understand the machines either, so I became an engineer for 20 hours a day until it finally had to be shut down because it was not making any money.

After that I got an offer to work in our packing plant – ‘No I don’t think so, I’m going to become a software developer.’ I had written some software for the production lines in the factory and

I thought I was a fully qualified software developer! I wrote a programme that let you press one button and send your contacts to a Word doc or a fax machine application. And then I added a quotation system for packing contracts, initially for dad’s firm and then I sold it to four American firms. But before I went on a sales trip to the USA I was told ‘we can’t let you sell this, it has too much of a competitive advantage’ because it used to take up to six weeks to work out a quote and this programme could do it in 20 seconds. I took all the good factory stuff out and sold the contact manager element, putting it on the cover disks of computer magazines. But I decided it was not selling well enough and after three months I shut it down, leaving me with a pile of blank CD’s.

Now I had to sell the disks. I went to see a potential buyer, George in the Forum Centre, but I was so nervous. When I was speaking to him I was playing with my hand under the desk. He bought a thousand, not a lot of profit but I just needed to be rid of them. On the way back to my car I felt a burning in my hand, I had dug through the skin on the palm of my hand, that’s how nervous I was!

I forgot all about it until two weeks later, George calls and asks if I had any more? Sure! But I didn’t! I called Virgin Media who then tell me that they are not making anymore. I ask about the cost of having them made for me under license, £1m! And you didn’t even get to meet Richard Branson! My dad calls and asks about the deal, I tell him about Virgin, he tells me he saw it coming and has bought me tickets to go to Hong Kong to sort something out, I got my sister to come with me to help and off we went.

Ticket to Hong Kong = spear and wilderness.

After eventually getting through immigration, stopped because I did not look British and then further challenged because I did not look Indian either, we call dad from the airport.

‘You were smart enough to book a hotel, right?’ ‘Yeah’, ‘Call me from the hotel, don’t call me from the airport.’

So, we get to the hotel. ‘Right what are we supposed to do dad?’, ‘That’s your problem.’ And he hangs up.

My sister says, ‘He is joking, call him back.’ So, I called him back ‘I told you once, that’s your problem’ and hangs up again!

We didn’t know what to do. I’ve never done anything like this, I’ve always been looked after. So, we went to see the sights of Hong Kong and were planning to do the same thing each day until we came home, to punish him for not telling us what to do. The next day I was coming out of breakfast, this story sounds so naïve now, and I saw the magic words hanging on the wall – Business Centre – wow. I didn't realise these things existed everywhere. We want to do business, let's go to the business centre! [More laughter]. They had two computers, a tired old lady and an enormous 100 volume copy of the Hong Kong Yellow Pages. Back in my room I phone for appointments and find a supplier in Hong Kong, but dad said no, then onto Taiwan where we got an arrangement he said yes to. I think he had decided before we left who he was going to buy from but was just putting us through the motions. We started the CD business, which was the beginning of my trading on my own.

Everybody wanted to be a distributor, all the retailers, so I had multiple brands. The problem happened when Philips sued the whole market for not paying the licence fee. It was a thirty-cent licence back when the price of a disk was $17, they'd never adjusted it and the disks had come down to $0.30. When they started chasing everyone we went unbranded, but there's no money in it because everyone says unbranded is ‘B-grade crap’ and I didn't want to sell any crap. So I bought the best stuff and sold it to the people who were buying the junk, which I realise is not smart business, I just didn't want to sell trash. But the business was effectively dead in terms of revenues.

So we switched to inks, which went very well and in three years we were the biggest in Europe. Then Epson sued us, said we were breaking their patents. We ended up settling for £0 five years later, but I had no business left. In the end I was only selling the ink so I could pay the lawyers!

I am very good at blowing them up

There was a Chinese company who used to supply me CDs, and a parcel appears on my desk just when I am desperate. It’s a tiny perfume atomiser, ‘can you help us to sell it?’ But it’s light and horrible, and they want to sell for £10, I didn’t understand it at all. Also, I didn’t have any money but then I thought, they used to give me credit when I bought CD’s, they trust me. Its light and can be airfreighted so I don’t need any cash to keep stock. Then one of the guys comes in from the warehouse ‘are you going to sell these, can I buy the sample?’ he told me it was for nights out, before a slow dance ‘a little spray.’ I figured I wanted to get into it but the best place would be for air travel. In the next three years we sold 11million in a partnership.

And then the partners tried to tell me what to do…and I don’t like being told what to do.

I offered to buy them out, they said no. I asked them to buy my portion, they said no. I took my share certificate out of my satchel, which I carried as proof that I was involved in a business based in China and I burned it. I made a list of the best swear words and used half (thought I’d preserve half for later) and along with my financial director walked out and never went back.

I come back to the UK. I have a huge warehouse which does all the distribution of this product, 45 people. I told them what was going on, I told them that they needed to find jobs. The last one to find a job took a full year and I kept them on until they found jobs.

Just like Tarzan

Everything up to then had been like Tarzan, just grab whatever comes along and I’ll swing until there's no rope left. This was actually the first time I'd had a blank sheet of paper, ink cartridges had fallen into my hands, CDs were a necessity of the software and now I had no clue what I wanted to do. But I understood a little bit about products and moving them around, and it felt safe to go and do that. So, I went to the Canton Fair, it is ginormous, and I am looking at everything from Christmas trees to tractors and I end up with 30 different samples which I give out to the family ‘if you don’t like something, just put it back on the sample table’. After a month none of the water bottles came back. When I ask for them back, they won’t give them back, and the guys at work are using them as well.

What follows is a Ted Talk tour through the processes of distribution, marketing and design. But at no point does it feel like a lecture, it is insightful and interesting, leaving me inspired to find a factory with holes in it and a bunch of scrap outside to turn into gold. Common sense is an overused phrase, Yusuf’s thoughts are not common at all, but they do trigger an ‘ah of course’ reaction. Choose bottle colours because they work in the house? No, choose bottle colours that match next year’s high street fashions. Are bottles the end game? No, they are a gateway product as almost every high street store sells water bottles so I have an ‘in’.

So, what is next?

Products wise, I have no interest. I want to let my own kids cut their teeth, maybe they can find a place that's comfortable for them. I don't want anything. I quite like Dundee, my car is already fine, my house is already fine. I can't think of what else I'd want to buy. My plan, if I get to my target sales price [for the business], would be to set up a non-profit venture capital fund with 80% of the money. The 80% would be more than enough to set up something to allow us to invest in smaller Scottish enterprises.

What makes you happy?

I don't believe in happy, happy is a choice.

A man has never had a TV before. One day someone comes along and delivers a 15-inch black and white cathode ray television. How does he feel? Another man has got an eightyinch plasma screen, take that away and give him a 15 inch black and white TV. How does he feel? Happy is a choice.

I don’t want to get lots of money, I’m not going to chase it. If you win something that doesn’t benefit you, you still lose and I think chasing money is one of those games where even if you win, you lose. I’m not talking chasing survival or chasing comfort or wellbeing. I don’t want to be chasing gluttony, more and more for no purpose.

Yusuf survived his wilderness. Not just Hong Kong, but myriad ‘tough love’ experiences involving aeroplane engineers, brillo pads, pre-pitch nerves and software writing. He is an infectious ball of energy, hilariously blunt and down to earth.

Restless and driven high achievers often appear to struggle with goal setting, there is always another mountain to summit and so happiness (indeed it is often a choice) is postponed until tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow. But regardless of Yusuf’s definition of happy, he sure looks happy.

The Man Who Rediscovered an Original Van Gogh

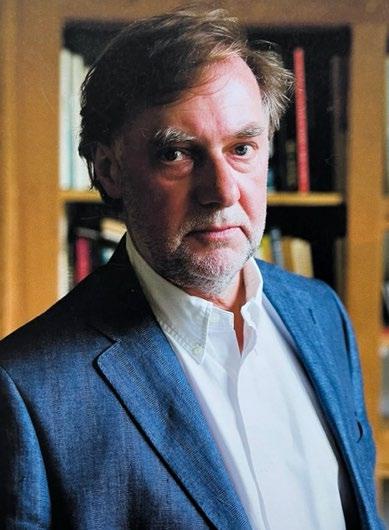

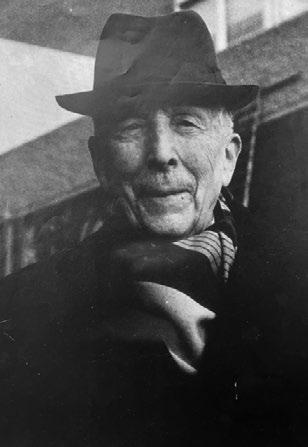

Before I met Ken Wilkie (class of 1960) in December we had exchanged emails. Enough so I could do a little background, gather some basics and start to think about where it would be interesting to take the interview, standard interview prep. We meet on a video call and after pleasantries Ken asks what I would like to focus on and we agree that I will ask questions to frame the conversation. We start with school days, is he still in touch, memories of teachers and what happened after he left?

I knew some of the answers already, it is no longer amazing what you can find out about a person before you meet them. But it is amazing how the mind processes new information, a pattern recognition machine with a bias towards order it treats information like a jigsaw, linking the pieces to form a coherent narrative. So it was oddly discombobulating, for a second time, when Ken reminded me that he was class of 1960. Nothing in his presentation, his recall or even his hairline fitted. But it is more than appearance, it is energy, vibrancy and passion. None of us aging at the normal rate should feel at all slighted by this description, Ken looks well for a man who is 80, indeed I have friends who are 50 and he looks well compared to them! For the avoidance of doubt I am reluctant to look into a mirror for several days after we chat.

The first discombobulation had been when he sent a photo of himself, his son and daughter on top of a Munro. The sky is blue and all three are beaming, the joy of the day shining brightly. I was going to write it off as taken some 20 years ago, but he had dated it as May 2022.

Ken enjoyed his time at The High, forming lifelong friendships he describes his time as ‘form setting, when I think back on it.’ He then talks about his time in L1b, aged 6, remembering his teacher Ruby Faulkner complementing him about a poem he had written and a story about a holiday in St. Andrews:

I remember the feeling of encouragement that it gave me as a wee boy and it went on like that, all the teachers were characters, Harry Potter couldn’t compete. Some were mildly eccentric but all of them were very strong academics.

It was the spark that lit the fuse, Ken went on to become an award-winning journalist and novelist, though his first steps took him further than over the road.

I didn't go to D.C. Thomson’s. I applied for a new course in media studies at Saint Martin’s College of Art, run jointly with London University and the London College for the Distributive Trades. It was an all-in-one education programme and I got a grant from the local Dundee education authority to participate. We studied copyrighting, photography, English, design, psychology, early television, all kinds of media subjects and at the end of the two-year course I had to decide what to do. I was very interested in photography, or do I go into advertising, copywriting or literature? Because I like writing stories and psychology, I decided to go for journalism and went to the School of Journalism in London. After a two-year course I went to work for a local newspaper, the Enfield Weekly Herald, and then I joined The Glasgow Herald. Between jobs, I cycled with my girlfriend through France to Italy.

I started at the Glasgow Herald as a sub-editor and then as a feature writer. They sent me to Africa and then to the Netherlands – ‘it has a reputation of being one of the most tolerant countries in Europe, get into that a bit.’ I arrived at a time when there were a lot of social revolutions going on. So, I talked to extreme Calvinists, I talked to liberal students, I talked to mayors, and I also gave my own impressions of travelling around the country.

The life of Rembrandt came into it and my impressions of the landscape the dominant sky, the Ruisdael Sky, as a traveller you see things with different eyes.

I liked the country and while I was there, I looked up an English language magazine called the Holland Herald, which was the in-flight magazine of KLM. I went to visit the office there, had a drink and they ended up doing a wee story about me doing a story about Holland. A year later, I got a call from the editor of the Holland Herald, ‘I read your story about Kenya, it was fantastic, would you be interested to come over and work for the Holland Herald as the lead feature writer?’ So, I decided, yeah, go for it, I didn't have many possessions – little enough to fit into my Renault 4 – and off I went on the ferry. That was the summer of 1969, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were making larger steps.

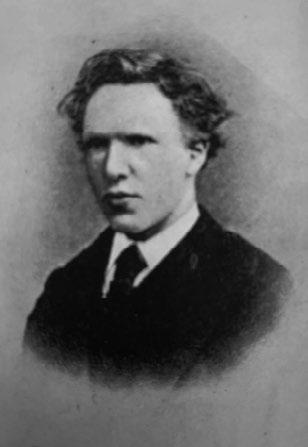

My first assignment was a cover story on the tercentenary of Rembrandt’s death and then I was sent off to Brazil, Suriname, Philippines, Japan and Australia. At the same time, I was doing profiles of Dutch artists like Rembrandt and M.C. Escher. In 1973 the opening of the Van Gogh Museum was coming up and I was asked to do a story about Van Gogh. I said, I’ll do it my way –give me three weeks and I’ll visit all the 18 different places in Europe that he lived to try to find out new things about him.

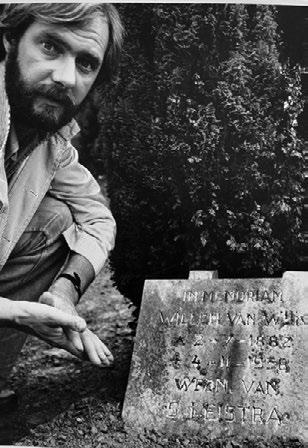

So, I started in Amsterdam where I met his still living nephew, who was 87. He introduced himself. “Van Gogh,” I replied “Wilkie” and with that handshake I realised that this was a man held in Vincent van Gogh’s arms, a living link in the story. From there I met a 96-year-old man living in a watermill who as a ten-year-old boy collected bird's nests for Van Gogh to draw, he described how he drew them and what kind of person he was.

Then to London, a lot of people didn't realise that he spent his early years, when he was 19 to 20, in London, working in an art gallery in Covent Garden, during which time he wrote to his mother saying that he'd fallen in love with his landlady's daughter. But she rejected him, he resigned from the gallery and within a very short period got deeply involved in religion, becoming an assistant minister in a church in Isleworth.

I wanted to know more about this relationship. I found a postman in London, who was also an amateur painter and had used his time during the postal strikes of the 1970’s to do research and found an address in Brixton that Van Gogh had been registered to. So, we went to the house together and the owner was kind enough to let us in. There’s now a blue plaque at the address. But I didn’t want to stop there…

The landlady’s daughter had rejected Van Gogh and married another man, Samuel Plowman. I found Samuel Plowman. They had a son, Frank, and I found his death certificate which was signed by his daughter, Kathleen Maynard and I looked up all the Maynard’s in the area: found all-in wrestlers and lots of crazy Maynard’s, before one person said, ‘I have a cousin, she’s who you are looking for, she lives in Devon.’

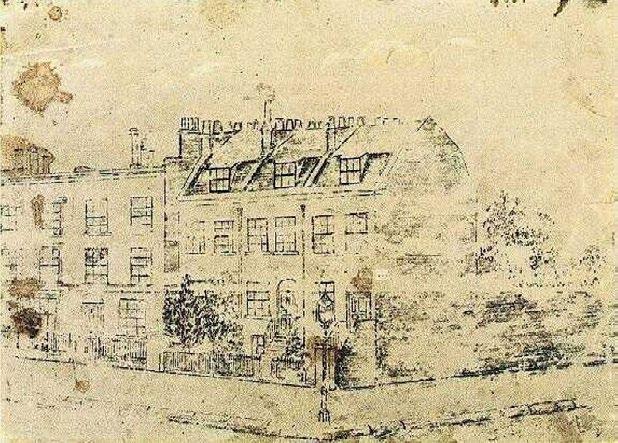

So I drove down, cup of tea, cucumber sandwiches, charming couple and then out comes a box, amazing because this is a wooden box with old glass negatives separated by greaseproof paper. I held one up to the light and there was Eugenie, the landlady's daughter, Kathleen's grandmother, standing at a table holding a letter. There are other photos; with children, in the garden, with an old tent on the beach and all from the 18701890's. We looked at the photos, nothing particularly interesting or relevant. Then as Mrs Maynard said, ‘I'll just put the box back up into the attic’, I noticed that in the bottom of the box there was a wee drawing, some tea/coffee stains on it, of a row of houses.

And then it happens. I see the name on the gate is ‘Loyer’.

‘that's your grandmother's house, I photographed it a few days ago. That's 87 Hackford Road, when Vincent was in London, he hadn't started painting, but he was doing drawings that he sent home to his sister and mother. I'm not an expert, but I wouldn't be surprised if Vincent van Gogh made this drawing. I've seen some of them at that stage and I can recognise a certain amount. I wouldn't be surprised if he'd made that drawing for your grandmother who he fell in love with.’

And she said, ‘ooh, better have another cup of tea!’

‘Mrs. Maynard, I'm at the beginning of a journey. I'm going to the mental hospital at Saint-Rémy, I'm going to Brussels, I'm going to Paris, I'm going to Belgium’s coal mining area. But I'm very willing to take that drawing back to Amsterdam and see what the experts of the Van Gogh Museum say.

She agreed and so it was taken, ultimately, to the professor of art history in Amsterdam University, Dr Hans Jaffe and after two weeks he authenticated it. Immediately I called Kathleen – I’ve got great news for you…

She was invited over to the opening of the Van Gogh Museum in March 1973, put up in a hotel and shown around Holland and Amsterdam. She asked, ‘Ken what I am going to do with it?’ I told her:

To be blunt, if you're really short of money, you can sell it, take it to Christies, Sotheby's or whatever. It’s maybe not of great aesthetic value, but there’s a great story attached to it, so it does have certain value. If you're not desperate for money, which I don't think you are, you can keep it in the family, put it in a safe, in the bank, whatever. Or you could lend it to the Van Gogh Museum. That way it's still your property and you review the loan every one/two years with an option to take it back to the family. But it could be on loan, kept in a museum and occasionally exhibited with other drawings at an appropriate time.

So, it was given to the Van Gogh Museum on loan. It was exhibited in different places, the Barbican in London, together with other drawings but the rest of the time it was just in a vault somewhere in Amsterdam. But Mrs. Maynard passed away and her daughter decided to take it back into the family in Devon. And they're just keeping it that way. Kathleen was in her late seventies back in 1972 and now her daughter is too, so that drawing will be passed on to the children eventually.

The discoveries led to Ken’s first book The Van Gogh Assignment, followed later by The Van Gogh File. I admit to Ken that I have a troubled relationship with art, but this story has me, Starry Night is a personal favourite piece, alongside the sculptures of Bernini, Antonio Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona and the contemporary work of Steven Brown (the Highland Coo guy). But I struggle with the idea of having something so fragile that it needs to be kept in a dark vault (or the rarefied and purified atmosphere of an art gallery) and so owning it means nothing more than knowing that it is yours, a stored cheque of uncertain value.

Back in the 1980s, I was spending the day with the founder of Abstract Expressionism in New York, Willem de Kooning. At the end of the day, he gave the photographer and me a drawing. One of his drawings. It was very expensive and like an idiot I put it in the frame and hung up in my house in Hilversum. It was a big house and it was broken into. But the de Kooning, nobody touched it. It was just a black and white drawing and whoever broke into the house was only interested in granny’s silver and left it hanging there. If you inherit anything don't put it on the wall, because people can find your address these days through the Internet.

As the call starts to wrap up he mentions that his great grandmother was the sister of golfer Tom Morris, that he once had the pleasure of interviewing Buzz Aldrin. There is also a story or two to tell about his time at the school. Conversations I hope to have with him in the months and years to come.

Ken is fascinating, as those with lives rich in experience often are. Production of a TV mini-series charting some of his adventures is in the early stages of development. Casting will be tricky, requiring a leading man of undistinguishable age! But I can’t wait to see it.