8 minute read

Doctor, Pioneer and Public Servant

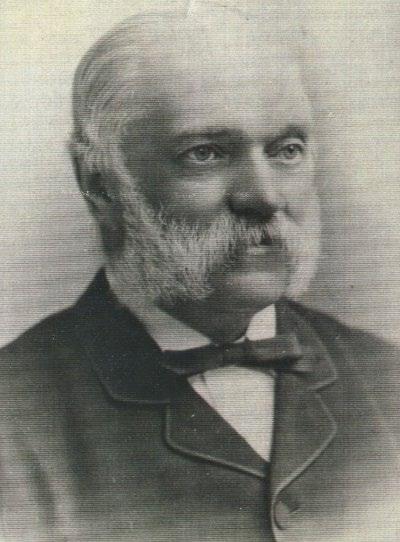

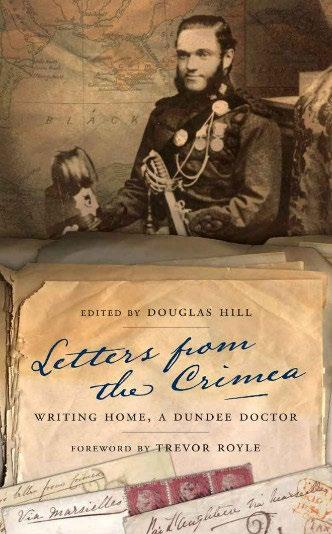

At The High School of Dundee we have a rich history, with many notable alumni. In this edition the youngest was born on the cusp of the new century in 1999 and the oldest is Dr David Greig, born in 1832. We are indebted and grateful to Roger Burns, class of 1964, who discovered Dr Greig’s connection to the school and laboured to put together this outstanding account of his life. A published volume of Dr Greig’s letters home also provided invaluable insight into his time serving during the Crimean War.

Dr Greig’s father had qualified as a surgeon and was a distinguished chemist, having his own pharmacy at 17 High Street. His mother sadly died at age 40 when David was nine years old. He attended school at the Tay Square Seminaries, then the Public Seminaries, the previous name of Dundee High School. He was inspired by his father, helping him to prepare medicines and at the age of 17 David assisted at the Dundee Royal Infirmary during the 1849 cholera epidemic. It is unclear exactly when he left school but in late 1849, he entered Edinburgh University to study medicine.

During his summer holidays, David with several other students “spent their mornings at Dundee Royal Infirmary and acted as dressers and clinical clerks. Of this experience he said – ‘the physicians and surgeons took an interest in us, showed us a great deal, and allowed us to do a great deal, so that afterwards when we went to any of the large medical schools, we found ourselves decidedly ahead in clinical work, and often astonished our teachers by our skill in bandaging, putting up a fracture, or by the assistance we could give at post-mortem examination.”

In 1850 at Edinburgh University David gained honours in his Anatomy class and the following year was awarded the Gold Medal in Senior Anatomy along with first prizes for both Practical Anatomy and Best Essay. On the 8 August 1853, David Greig graduated M.D. with honours and shortly after became Demonstrator of Anatomy and a lecturer at the University. But with casualties rising in the Crimean War, Dr Greig was selected to go to Crimea by his University Professors Simpson and Syme, funded by a donation from Lord Blantyre he departed for Constantinople in October 1854.

Within a week of arrival, he was looking after 180 patients in two wards (and half a corridor), with days typically including two amputations. In a letter home to his sister Anne, he writes:

“My great object in joining the army was, in the first place to get surgical practice, to see the world, to get the éclat of being at the war, and to get a year or two’s recreation before settling in practice”. He notes that the “Russian bullet is a good deal larger than the English one” and striking a femur does considerable damage, often requiring amputation.

In a subsequent letters he wrote:

“You ask about Miss Nightingale – when on board the Vectis I did not know who or what she was, but since then we all know her very well. She is a very kind lady and what is more has £8,000 a year, which we all joke about here. The nurses are all under her charge, sometimes we get a visit from her in the wards and if a nurse is required for a patient, she sends one. At some parts of the hospital, they attend every day and dress the patients, but to do that at all the hospitals, would require 50 times the number. She keeps strict watch over them and they work very well, but I think just the same could be done by the orderlies which we have always in our wards (soldiers who act as nurses)”.

“I had a farce with Miss Nightingale today, she was visiting some of my patients who were very bad and was asking one poor fellow who had got his leg shot off and was complaining of thirst, if he would like rice water or barley water to drink? He thought for a little and then said, he would prefer brandy and water if it was all the same to her!”

“I suppose you have heard of the celebrated Major Alexander Ungelisopilo who was found stabbing the English lying after [the battle of] Inkerman. He had received a wound through the shoulder joint and died under my charge three days ago. I took his shoulder as a souvenir – a memento of the brute”.

“People always say ‘do let us publish some extracts [of the letters] and we will be careful what we publish’, now what could have been worse than publishing that the Russian Major had been cut up and his shoulder kept as a memento, it might have offended some of our Government as being a thing to irritate Russia. The best joke about the Russian Major is that I have not got his shoulder after all, for when I put it into a jar to macerate the rats took it out and devoured it”.

In January 1885, Dr Greig was relocated and now had some 77 Russian prisoners and about 500 English to tend. He mentions that many of the cases are frostbite and there are few operations. Dr Greig recounts: “A man of the 30th Regiment was brought down from the Crimea with his feet frostbit and was put under charge of one of the doctors here. I had nothing to do with him but one day the surgeon who has charge here took me to him and asked what should be done. I told him that he ought to amputate one of the feet at the ankle joint after Syme’s method. He said he would rather amputate below the knee as he was not acquainted with the operation, having been all his days at the Cape of Good Hope. I took him to the dead house and showed him how to do, he said, ‘My fine fellow, it is a beautiful operation but I can’t do it, you must do it’. We had a consultation of all the staff and everyone spoke against it, but as I insisted on it I am glad to say I have saved a nice young fellow’s leg, besides getting a great deal of credit from all my companions, and the result is that all the bad cases are sent to me, which is very good”.

September 1885 – Dr Greig was asked if the “hospital was in tip top trim and how many empty beds we had for wounded men as we had a good chance of getting them filled tomorrow”. In his next letter home, Dr Grieg states that “Sebastopol is taken at last”, he relates how the retreating Russians set fire to the town and to their ammunition dumps. “After the Russians had left the Kedan there was a tremendous lot of wounded brought to us, both English and Russian, and within about two or three hours I think I saw 2,000 patients”.

By mid-May 1886, the 17th Regiment had departed for Canada but Dr Greig was required to remain, performing his pathological duties. In a letter to his father in June, speculating that he will be departing soon: “It appears that it is about time I was beginning to think seriously what I intend to do. I do not consider that the last two years have been altogether lost to me. I would not have missed seeing what I have seen for any sum of money and only regret that I was not with the Army from the very first. Oh, how splendid it would have been to have shared in the victories at Alma and Inkerman, but it could not be helped.”

Dr Greig was awarded the Crimea Medal and the Turkish Medal for his wartime service. He is listed as being in the 90th Regiment, with regimental number 3970.

After his service ended he returned to Dundee and a newspaper insert stated that “Dr David Greig, Surgeon, begs to intimate that he has commenced the PRACTICE of his PROFESSION at Burnhead House, Top of Seagate. Surgery – 17 High Street. Dundee, 13th November 1856”.

There was a public petition to shut the Howff, a well-known burial ground near the High School of Dundee, as it was considered injurious to public health and offensive to public decency and many witnesses were called to the Sheriff’s Inquiry. Dr Greig was called for his opinion, based on his experiences of graves at the Crimea and personal visits to the Howff, stating that in his opinion there were no ill effects on gravediggers performing their work.

Dr Greig was in 1858 appointed Physician to the Baldovan Asylum for Imbecile Children and remained involved for many years.

The Aberdeen Press and Journal of 22 February 1860, published the following report, as did several other publications:

“Acupressure” for Arresting Haemorrhage. —Professor Simpson, of Edinburgh, writes a letter to the Medical Times on the subject of acupressure, which is a new mode of stopping bleeding after amputation by the use of metallic pins or needles for closing up the arteries instead of binding their ends by means of ligatures.

Professor Simpson refers to the innocuousness of bullets, pins, needles, &c., which may lodge in the body for a long time, and quotes from letters his friend, Dr Greig, of Dundee (a rapidly rising man in his profession), showing the ease and simplicity of the mode invented by Professor Simpson, recently tried by Dr Greig with great success, in each case the patient benefiting by the change of process. Dr Greig, who has been the first to test the Professor’s suggestion, says “nothing can be easier, and if a surgeon uses it once, I am sure he will do so again.”

He features on several occasions in the media expressing his expert opinion on a variety of incidents, one example being how struck he was by the high incidence of severe accidents among female mill workers arising from loose sleeves which were then fashionable, and Dr Greig recommended that workers have bare arms. He is noted as being the certifying surgeon under the Factory Acts.

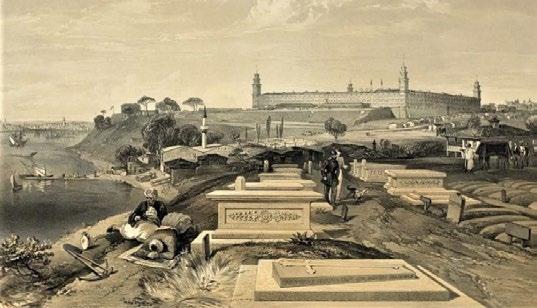

In February 1980 he again ventured east. First visiting Constantinople, finding that the local customs have much changed, with cigarettes instead of Chibouk pipes, and ladies’ face coverings less common. He then visits Scutari, finding the cemetery beautifully transformed. He recalls he felt ill, and subsequently realised that it was the beginning of a fever.

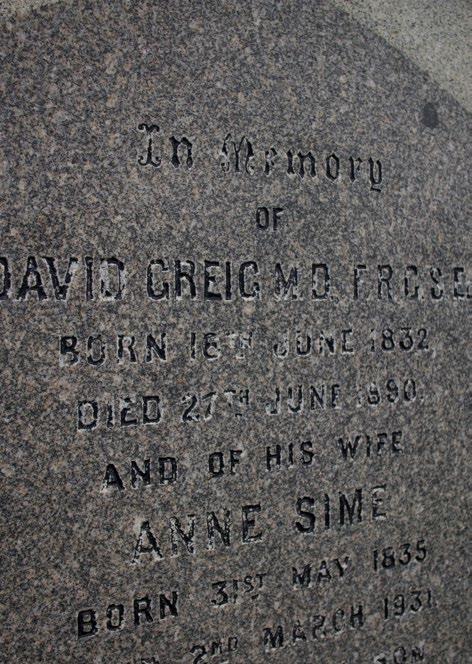

The first news of Dr Greig’s ill health was given in the Dundee Courier 12 June 1890 when the Rev. Colin Campbell expressed dismay that Dr Greig, “one of the honoured elders of the Church of Scotland” and who had been the first to attend to his own recent illness, was himself seriously ill with typhoid fever. A short improvement in his condition was noted but serious relapse followed, and he died on the 27th June. A succession of newspapers including those of Edinburgh and Aberdeen lamented his passing, as did the Dundee Advertiser of 28 June 1890:

As a citizen he was jealous of the honour and credit of his native town, deeply interested in every movement affecting is welfare, and full of information on the changes in its structure and the vicissitudes of families. As a man he was distinguished by his simplicity, guilelessness, and sincerity. Any affectation, hypocrisy, untruthfulness, or unreality he could not away with. His estimates of men and things were based on facts, and though it may be that other facts, if known and admitted, might have modified his estimate of a character, still he was always just and seldom ungenerous. With a punctuality and method of which he was reasonably proud, with a diligence that never flagged, and a self-forgetfulness so entire that it was almost unconscious, he has gone his rounds of duty day by day for more than thirty years, and now, to use a favourite phrase of his own, “he has fallen asleep and entered into his rest”.

The elder of his two sons, Dr David Middleton Greig, followed his father into the medical profession and had a distinguished career that included service in the Boer War.

Dr David Greig has been added to the roll of notable alumni and a plaque celebrating his life is on display in the school.