10 minute read

Bill Macfarlane Smith

Up In The Clouds: FP Recalls Conquering the Climb to Everest Base Camp

Dr. Bill Macfarlane Smith left the High School of Dundee in 1960. A graduate of the Universities of Aberdeen and Reading, he maintained his links with the School over many years, having a major involvement with the Old Boys’ Club, the Patrons, the Trust Fund Appeal and the Parents’ Association. He was also a member of The School’s Board of Directors for many years, standing down as Vice-Chairman in 2009 to free up time for his position as District Governor of Rotary District 1010, which covers a large area of Scotland. In this article, Bill recalls his adventure of a lifetime – hiking the perilous paths to Everest Base Camp.

Almost exactly twenty-five years ago, I sat one evening with the warm early summer sun streaming through the open door, concentrating on my equipment requirements for a trip to a far corner of the world later that year.

However, this story has a much earlier beginning, back in 1950. For once, I had completed all the classwork required to the necessary standard. My reward was to be allowed to go to the school library to choose a book which I could read. I was fortunate that one of the first books I picked up, though dusty and clearly little read, contained an account of the early 1920s British expeditions to explore and hopefully scale Mount Everest, already recognised as the highest mountain in the world. One of very few photographs showed a huge mountain, its summit almost totally obscured by cloud and wind-driven plumes of snow. I was fascinated and totally hooked. I could hardly wait to finish the book and move onto the very few other existing books on the same subject. My fascination jumped up several additional notches on the news in 1953, that a British expedition led by John Hunt had put the climbers Ed Hillary and Tensing Norgay on the top.

In the years which followed, I read every book I could find on the different ways in which Everest could be climbed. Some were less successful as others and throughout the death toll was appallingly high. There the matter might have rested but for my attendance many years later at the Dundee Mountain Film Festival. The principle speaker was the world-renowned mountaineer, Sir Chris Bonnington. His talk that evening was about the various expeditions which he had led to Everest and always given up his own personal opportunity to get to the summit to be certain that at least one member of his team would do so. He had finally achieved his own ambition by joining an Austrian expedition. Always a very gregarious person, he spent a lot of time chatting to the audience after his talk. In my own conversation with him, I talked about my own interest in Everest but thought that I was too old to ever go there. He looked me up and down very searchingly, then said, ‘You still look very fit. If you really want to go there, what is stopping you?’ So, after some months of physical training and proving that I was fit enough to go, I found myself in the departure lounge at Edinburgh Airport, en route for Kathmandu via Gatwick, Frankfurt and Dubai. Kathmandu was a different world – the airport was a heady mix of sheer bedlam, noise and, already, evidence of extreme poverty, as individuals vied, often quite violently with

each other, for the privilege of carrying your bags. As some of this contained equipment essential to our trip, we had more than a measure of apprehension. It was a relief to be safely in our hotel for a few days to recover from our journey and the time zone shift, and to see some of the famous sights of the city, such as the Monkey Temple.

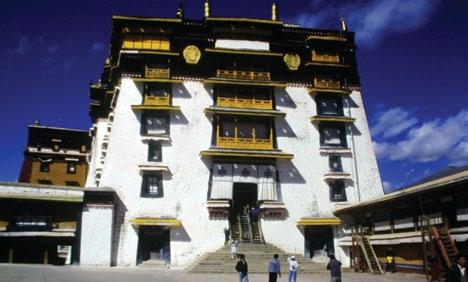

The plan then was to travel in a rather dilapidated bus along the Friendship Highway, linking Kathmandu to Lhassa in Tibet, via another Nepalese city, Bhaktapur, noted for its Buddhist temples. Some of these were in a very bad state of repair, often leant precariously and must have almost certainly succumbed to the various earthquakes since then which have wreaked havoc in an already impoverished country. The following day we would disembark at the town of Balephi to start the process of acclimatisation in the relatively low Jugal Himal mountains in Nepal, which was essential to cope with the much higher altitudes later on, then travel to Tibet and eventually up the Rongbuk Valley to Everest itself.

When the instruction came to ’Get your rucksacks on and start walking’, it was like entering a different world. The initial roads were just dirt tracks and the subsequent paths barely visible through the vegetation. The whole of this steeply sloping countryside was terraced for cropping, and quite often our route was simply along the edge of one of these terraces. We gained height steadily over a number of days, and where it was possible to get a view through the vegetation, it was impressive to see how much height we had gained from our starting point, by now far off down the valley. In the very first days we came to grips with something no one had warned about – leeches. They are sophisticated enough to land so lightly that you are not aware of them and inject a chemical where they have bitten you to stop your blood from coagulating. We just had to accept them, as there was no repellent which could stop their attacks. We were then into real monsoon conditions, and the volume and intensity of rainfall meant a regular soaking, irrespective of any waterproof clothing. In any event, it was so hot and humid that to put on waterproofs only added to discomfort. We soon preferred, like the native Nepalese who were our porters for the heavy equipment, just to get wet.

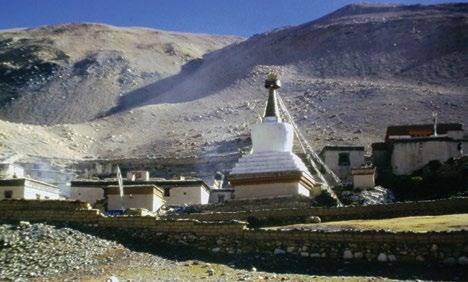

After several days, it became obvious that the temperatures were falling and the rain easing, though sometimes replaced by snow. By the time we got to our acclimatisation camp at the holy lake of Bhairev Kund at just over 13,000 feet, we were pitching our tents on lying snow. The holy lake is a point of pilgrimage for Buddhists, which they go to often at the worst time of the year weatherwise, when there are no crops to tend at home. They mark their visit by leaving in the water of the lake, small decorated tridents.

Our stay there was cut short by even heavier snow and after the ascent of one peak at just over 14,000 feet, we made our way by some very steep descents, often over green, slimy rocks due to the high rainfall, back to the Friendship Highway. Part of this involved a traverse along the Precipice Path, only the width of one foot, a 300 foot drop down a 70 degree plus slope to rocks and the river, and with no rope for security. The fact that I survived this was down to the famous Dundee High School ‘stickability’, in dealing with adverse situations, and the fact that the porters

had already gone ahead with all our food and equipment! To turn around was next to impossible and even then, would have involved a three-day detour to rejoin the group.

After a 7,500-foot descent, we reached Tatopani, the border crossing point between Nepal and Tibet, at a height of 5,000 feet. There were regular halts where we had to by-pass, on foot, major rockfalls which had destroyed the road, but eventually we finished up at Tingri/Shegar, one of the staging points for the 1920s British expeditions, at just under 14,000 feet. By now we were on an upland desert, so different to the tropical forests only a short distance to the south.

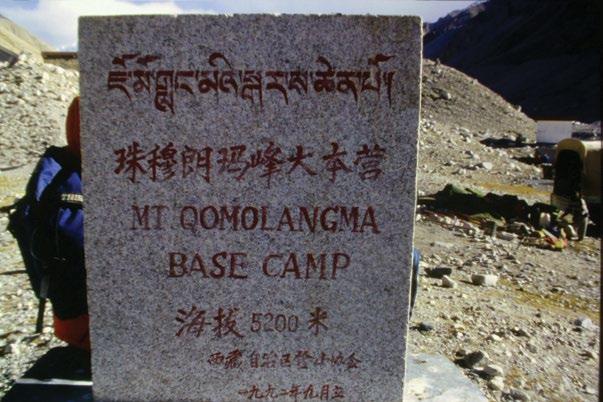

Two days more and regular stops at Chinese army inspection posts, a crossing of the Pang La at 16,400 feet, and we arrived at Everest Base Camp North at 17,700 feet. For the last part of our journey, we were shut away in the back of a truck with no outward view. Absolutely nothing can prepare you when you get your first view to the south and see the enormous height and bulk of Everest. Even my familiarity with the high mountains of the Alps was no preparation for this. Life at Base Camp was incredibly lazy, both to recover from our journey and to acclimatise further. Another highlight of our trip was to try our fitness by heading further up the mountain, though only two of us were adequately acclimatised to be able to do so. The track started off downhill, squeezed between the east side of the glacier and the east wall of the valley, and was clearly subject to quite regular rockfalls from the hillside above. It then started to slope uphill again. The going was not difficult, but it seemed to take a long time to get anywhere in the thin air. Before long we had reached the point where it was possible to diverge from the main valley into the East Rongbuk valley and glacier.

I reached this point with very mixed feelings. It was the limit of the permit granted to us by the Chinese to proceed up Everest. Although tired and blowing quite hard to get this far, I was in no doubt that with further training and acclimatisation, I would have been capable of going quite a few thousand feet higher, even though at this relatively low stage I did not have the benefit, or need, of the bottled oxygen which climbers use routinely when they get to the final 2,400 feet of the climb. Against that, there was an understanding of the sheer unpredictability of the weather higher up, and the very narrow margin between survival and success, and the one mistake in judgement which would almost certainly be fatal.

Back at Base Camp, my one remaining commitment was to walk to the monument to Mallory and Irvine who may well have reached the summit in 1924 but perished in the attempt. It was a privilege to acknowledge the courage and commitment of these two men and their colleagues. With equipment little more protective than what we wear today in a Scottish winter, what they achieved was astonishing. I still treasure a copy of a picture of Edward Norton taken at over 28,000 feet on Everest, where his concession to the weather was puttees to keep the snow out of his boots, a thick woollen jersey, a sports jacket with the collar turned up, a scarf and a felt hat, plus the obligatory leather gloves. Magnificent! Our journey thereafter seemed to fly by, and it was not long before I boarded my flight back to Kathmandu where I had one last spectacular view from the plane of Everest, once again wreathed in clouds with its traditional snow plume blowing out from the summit. The journey back to London, then Edinburgh, was an anticlimax and seemed interminable. The impact of my expedition was only brought home to me when my wife and youngest son failed to recognise me when I came into the terminal building at Edinburgh. This was due in part to the beard I had grown, and a loss of some 35 pounds due to the combination of exertion, inadequate nutrition and the acquisition of hookworm, one of the endemic diseases in Nepal.

Would I go back again to try to get higher? Probably not nowadays, but it was the trip of a lifetime and I have always been grateful for the words, and the challenge, laid down by Sir Chris Bonnington.

Bill Macfarlane Smith, Class of 1960