19 minute read

Anthroposophical Views Dora Wagner

The Heilpflanzengarten of the Anthroposophical Community Hospital in Herdecke Dora Wagner

2020 marks the centenary of Anthroposophical Medicine. Over Easter 1920, in a series of lectures to young doctors, Rudolf Steiner presented his ideas for a new, modern, integrative medicine for the first time. Later, Steiner worked with the Dutch physician Ita Wegman and the Austrian pharmacist Oskar Schmiedel to develop these impulses into an overarching medical-therapeutic concept based on a holistic view of the human being.

Advertisement

Ita Wegman (1876-1943) was a very special woman, far ahead of her time; she was one of the first women to study medicine, becoming a courageous and cosmopolitan doctor. In 1921 she founded the first anthroposophical clinic, in Arlesheim in Switzerland, in order to implement these new approaches to holistic medicine.

Oskar Schmiedel had begun developing the first anthroposophical medicines as early as 1912. In the following years, new formulations and manufacturing processes for holistically-oriented remedies were developed. By 1921 the results of these early endeavours had found their way into pharmaceutical practice, and the first commercial anthroposophical medicines were produced. At that time, 46 preparations were already comprising an ‘official’ list to be produced in an experimental laboratory in Arlesheim. From 1928 this laboratory was named WELEDA, and it remains the world's leading manufacturer of holistic and anthroposophical medicines to this day.

In 1935 another company was founded to produce anthroposophical medicines, this time in Germany. WALA was established by Rudolf Hauschka, and took its name from the initials of its manufacturing processes; Warmth—Ashes, and Light—Ashes. The company still produces around 900 medicines that address the human being holistically, and both WELEDA and WALA maintain huge medicinal plant gardens to cultivate the herbs that are harvested and processed into remedies.

1969 saw the inauguration of the first anthroposophically oriented hospital in Germany: the Herdecke Community Hospital (GKH). The founding members considered it important that medicinal plants be studied on-site and that medicines be produced from home-grown herbs, and so a medicinal plant garden was also created. During and outwith her working hours, the hospital pharmacist was also engaged in gardening, and was responsible for the production of anthroposophical medicines from the herbs.

Nowadays, much has changed. Financial restrictions, new laws, and the dearth of time, mean that only tinctures and ointments from selfgrown Calendula officinalis (Marigold) and Echinacea purpurea (Purple Coneflower) are produced in the hospital’s pharmacy today. Needless to add, the pharmacist hardly finds time to take care of the plants; the garden fell into disuse some five years ago. So, since March of this year, I have become responsible for this herb garden at the Herdecke Community Hospital. I teach Medicinal Herbalism at the University of Witten/Herdecke, where courses in the Faculty of Medicine also include plant excursions, gardening and the production of anthroposophical medicines. With the help of some of the medical students, I am trying to rebuild and re-establish this hospital garden. The garden is open to the public. Doctors and nursing staff spend their breaks here, patients meet their relatives or simply enjoy being in nature and not in their hospital rooms, sometimes sick people are even wheeled around the garden in their beds, or doctors hold consultations with their patients in the open air. Since all visitors are very interested in medicinal plants, they take pleasure in talking to each other about healing herbs— not about diseases —and in planning to make the garden more beautiful and more pleasant. For this reason, I have begun holding a fixed ‘consultation hour’ so that visitors can talk to the gardener.

With the next issue of Herbology News, I will begin to report regularly on my encounters in the medicinal herb garden at Herdecke, and on anthroposophical approaches to the plants that grow there.

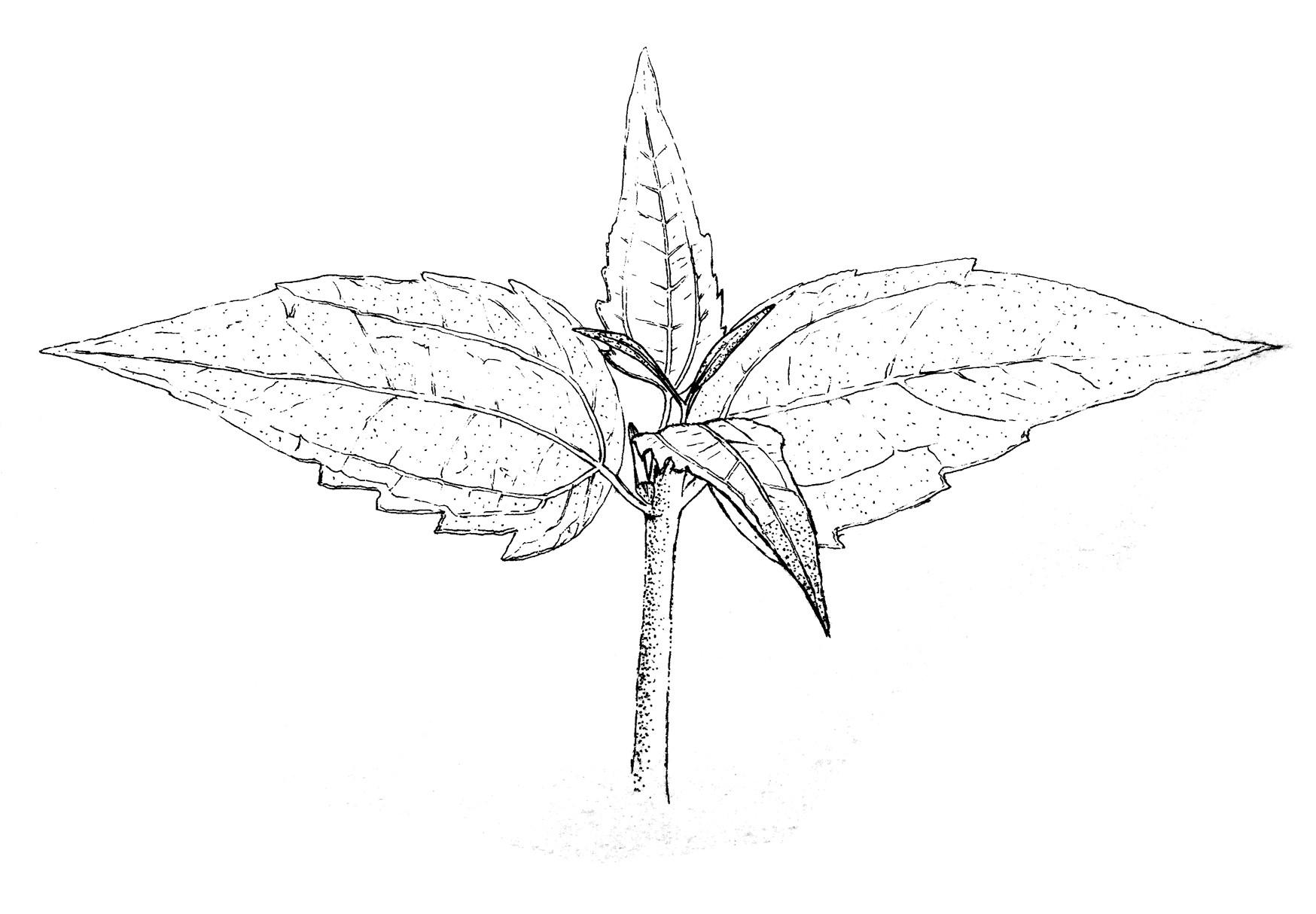

Nya Falang Ramsey Affifi

My first encounter with this startling plant was during my years in rural Laos. Wong’s youngest, Kongngeun, was halfway up a ladder poised against a Mango tree. With machete in hand, her tiny bare feet toddled on its rickety bamboo rungs. I lifted her down and put away the ladder. Scarcely understanding the consequences of what was to transpire, she bumbled towards me, her bright eyes sparkling and her great blade swinging. To this day I wonder what she was feeling. Her twoyear old face seemed full of innocence, without a speck of anger. And yet, the machete arced fatefully towards my protesting hand. Moments stretched out— in vain —as its metal edge approached and then lodged itself into the top of my thumb. Her face melted into fear. Wasting no time to scold, Wong sprinted to a nearby Pineapple field and emerged seconds later with a clump of bright green leaves. I recognized the plant immediately as Nya Falang; that sticky, pungent plant I had spent months weeding in a nearby Mulberry orchard. He chewed it into paste and slathered it onto my gushing wound. The bleeding stopped immediately. Thumb bandaged, I later reflected on what had happened.

Speeding up platelet aggregation (the mechanism I supposed in play), slows down bleeding. Two opposing rates of change held together a single process. In scientific articles, I later learned Chromolaena odorata accomplished this haemostatic feat by changing the rate of activity of some genes in my thumb’s fibroblasts (Pandith et al, 2013). Different temporal shifts coordinated across different biological scales. The protagonists in this timeshifting wizardry are stigmasterol, scutellarein tetramethyl ether, flavonoids, and chromomoric acid, which seem to serve antiherbivory and antibacterial roles in the plant’s defense (Vijayaraghavan et al, 2017). Incidentally, these chemicals are likely toxic to the plant itself, and so are normally stowed away in the plant cells’ vacuoles. Wong’s teeth had to cut the cells open so the plant could heal my own cut open cells.

C. odorata’s regional names hint at its sharp and then haemorrhagic arrival into various people’s natural history. Known as ‘French Weed’ (ຫຍາຝະຣງ, Nya Falang) in Laos, but as ‘Herbe de Laos’ in France, C. odorata is actually native to Central America, the Caribbean, and the Northern part of South America. Since the mid 20th century, it has spread rapidly, with now pan-continental distribution in tropical and subtropical climates (though apparently with minimal presence in Australia). When I google ‘world’s worst tropical weeds,’ C. odorata comes up ahead of other notorious troublemakers of the global South, including Imperata cylindrica, Cyperus rotundus, Commelina benghalensis, and Eichhornia crassipes. Its prolific habits damage cropland, lay waste to pasture, and ruin plantation productivity. The same chemicals that saved me a long and bumpy journey to a local health centre and perhaps a serious infection, undoubtedly contribute to its ecological success and its reputation as a scourge.

Emerson’s (1880) notion that ‘a weed is a plant whose virtues have never been discovered’ will seem naive and dangerous to most farmers. I have seen enough family crops cramped and cluttered into oblivion to sympathize with those who despise C. odorata. Nevertheless, I have benefited from

the virtues of this pungent coagulator. Not only did it heal my hand, it thrust into consciousness the surprise of discovering hidden powers in commonplace things. The humdrum prevalence and perhaps even the menace of highly successful plants sets them up to shatter our preconceptions all the more forcefully. We should be grateful for these ruptures and, indeed, seek them out.

I do not mean to suggest there is no place for controlling this or any other weed. Agriculture, in any foreseeable future, depends on it. But I wonder if it is possible to appreciate even the vigorous plants we commit to weaken or kill, that their life be taken through acts that pierce hatred with gratitude, to speckle their tedious annihilation with flecks of wonder.

Illustration: Ramsey Affifi References Emerson, R.W. (1880) Fortune of the Republic, in Prose Works. Boston, MA: Houghton, Osgood & Co. Pandith, H.; Zhang, X.; Liggett, J.; Min, K-W, Gritsanapan, W. & Baek, S.J. (2013) ‘Hemostatic and Wound Healing Properties of Chromolaena odorata Leaf Extract’, ISRN Dermatology Article ID168269, pp. 1-8. Vijayaraghavan, K.; Rajkumar, J.; Bukhari, S.N.D.; Al-Sayed, B. & Seyed, M.A. (2017). ‘Chromolaena odorata: A neglected weed with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities’, in Molecular Medicine Reports, vol.15:3, pp. 1007-1016.

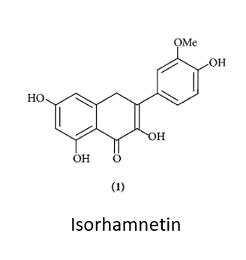

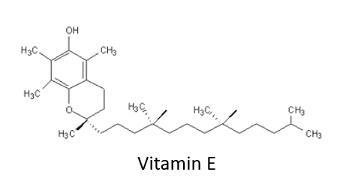

Sea Buckthorn: The Wonder Berry Dr. Michelle Armstrong

Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) is a small, spiny, deciduous shrub found widely in Northern Europe and Asia (Sayegh et al., 2014). The orange berries are used in the treatment of a variety of ailments including gastrointestinal disorders, menstrual disorders, skin diseases, and asthma (Larmo et al., 2014), and in reducing the risks of cardiovascular disorders such as high blood cholesterol, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis (Eccleston et al., 2002). We are all aware of the positive link between heart health and the consumption of fruit and vegetables; this is due to their high antioxidant level (Esfahani et al., 2011). Sea Buckthorn contains a huge amount of antioxidants including Vitamin E, Vitamin C, Carotenoids, and Flavonoids. In fact, this small berry is reported to have the highest concentration of Vitamin C when compared to other berries (Sayegh et al., 2014). But what is the importance of these antioxidants in the human body?

Antioxidants are naturally-occurring chemicals that are found in some enzymes produced by our bodies, as well as in some foods, such as fruits and vegetables. They work by blocking potentially harmful oxidation reactions. Oxidation reactions are chemical reactions that involve a transfer of electrons from one molecule to another. This transfer process can result in the formation of free radicals. Electrons like to be in pairs, but free radicals are molecules that end up with an uneven number of electrons. This makes them unstable, easily reacting with other molecules in order to steal their electrons and gain electron stability.

Oxidation is a necessary process, occurring in the human body through normal physiological functions like digestion and breathing; however, a balance between the number of free radicals and antioxidants is required to ensure these bodily functions are healthy (Lobo et al., 2010). If the number of free radicals cannot be regulated by the body, a condition known as oxidative stress can occur. It is this oxidative stress that can adversely alter human cells, resulting in diseases such as atherosclerosis (clogged arteries). The high antioxidant concentration in Sea Buckthorn offers electrons to stabilise the free radicals, thus counteracting the catastrophic chain of chemical reactions that can lead to cardiovascular disease. It’ s no surprise Sea Buckthorn is known as ‘The Wonder Berry’ within the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries. Now you know it’s good for you, so the only decision you have to make is whether you want to try it as an ice cream, or in a whisky cocktail…

References Eccleston, C.; Baoru, Y.; Tahvonen, R.; Kallio, H.; Rimbach, G. H. & Minihane, A. M. (2002) 'Effects of an antioxidant-rich juice (Sea Buckthorn) on risk factors for coronary heart disease in humans’, in The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 13: 34635 Esfahani, A.; Wong, J. M. W.; Truan, J.; Villa, C. R.; Mirrahimi, A.; Srichaikul, K. & Kendall, C. W. C. (2011) ‘Health Effects of Mixed Fruit and Vegetable Concentrates: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Interventions’, in Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 30: 285-294 Larmo, P. S.; Järvinen, R. L.; Yang, B. & Kallio, H. P. (2014) ’Sea Buckthorn, Dry Eye, and Vision’. Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A. & Chandra, N. (2010) ‘Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health’, in Pharmacognosy Reviews, 4: 118-126 Sayegh, M.; Miglio, C. & Ray, S. (2014) ‘Potential cardiovascular implications of Sea Buckthorn berry consumption in humans’, in International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 65: 521-528 See also: Suryakumar, G. & Gupta, A. (2011) ‘Medicinal and therapeutic potential of Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.)’, in Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 138: 268-278

Garlic & Leaf Fall Ruth Crighton-Ward

At this time of year, we are starting to prepare the garden for the oncoming winter. The clocks go back, and the nights get longer and darker. In Central Scotland the frosts usually start around the latter part of November. Unfortunately, due to climate change, the more recent winters have become warmer and wetter than previous years and tend to bring heavy winds and rain. Much of the work done in the garden towards the end of the year is about preparation for the following year. There is still some weeding to be done, but on the whole growth has started to slow down.

In November, then, our tasks include protecting plants which could be at risk from the more extremes of weather. Horticultural fleece can be placed around plants which are susceptible to frost damage; it helps to keep the soil at a slightly warmer temperature as well as providing some shelter from the wind. For some more vulnerable plants, cloches can be placed over them to provide protection from the elements. It is also important to stake plants which are taller and could be damaged by the wind. This is also the time when ornamental spring flowering bulbs should be planted. Plants such as Tulips (Tulipa spp.) and Daffodils (Narcissus spp.) provide some welcome colour during March and April. For even earlier flowering, also plant Snowdrop bulbs (Galanthus nivalis).

Planting Garlic (Allium sativum) is a job to be done now, so your Garlic will be ready for harvest around June next year. As a medicinal herb, Garlic has been revered for thousands of years. It was prized by the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians for its ability to fight off illness. Some of its benefits include boosting the immune system and reducing blood pressure. It’s a powerful antibiotic and good for detoxifying the body. Garlic can be planted anytime between October and February, but I prefer to plant it in October or November, as the cloves require a spell of colder weather to develop into bulbs. It is best to get it in the ground so it can stay there throughout the winter. Garlic can either be soft necked or hard necked. There are currently over 600 named varieties, so it’s worthwhile researching which varieties may be best for your needs, soil type etc. prior to purchase. One of my personal favourites is a type of soft neck garlic called “Solent Wight”. It’s extremely hardy and produces large cloves which can be stored for a long time.

Split the bulbs into individual cloves, but only do this immediately prior to planting— if left for a while, individual cloves can dry out. On average, each bulb will provide 8-10 cloves. This year, I planted 8 bulbs which gave me 67 individual cloves. Each of those cloves will form a new bulb. Choose a sunny spot. Garlic can be grown in the ground or in pots, if you are short of space. One of the advantages of growing in pots is they can be moved if the first position isn’t sunny or sheltered enough. Plant each clove below the surface of the soil, around 10cm deep. If Garlic cloves haven’t been planted deeply enough, they can be pushed to the surface as the soil freezes and expands. The flat part of the clove should be at the bottom, with the pointy part facing up. If planting in rows, allow 10-15cm between each clove and 30cm between rows. A small tip here is not to cover the cloves until all have been planted. That way, you can check the spacing of the cloves and adjust as required. Cover with soil, and that is basically it. They will not require watering unless there is a particularly dry spell, which is unlikely at this time of year.

Elsewhere in the garden, leaf clearance will have started in earnest. Although fallen leaves can provide shelter for insects, they can also harbour pests and diseases. On grass, they can lie in damp clumps depriving the plants underneath of sunlight. If you have a pond or water feature, it’s a good idea to place netting over it to prevent leaves falling in. The leaves will decompose in the water and release nutrients and gases which can be harmful to aquatic plants and wildlife. A good way of using those fallen leaves is to create leaf mould. Rake the leaves up from lawns or driveways and place in sacks or binbags. Add some water to keep the leaves moist, then tie the bag loosely to allow you to open them on occasion. Pierce a few holes in the bag for ventilation. Place the bags somewhere out of the way, such as behind a shed, and leave them. Don’t expect them to be ready after a couple of weeks; gardening is a great way to teach us patience. This is a slow process; it can take up to two years for the leaves to break down. When broken down, the leaf mould should resemble tea leaves and can be used in a variety of ways. On its own it is not as nutritional as compost. However, it does make an excellent soil conditioner. For instance, if your soil is heavy and clay-like, then adding leaf mould can make it more manageable. It can also be spread round the base of plants as a mulch. When combined with compost, it can make a great potting mix. If blended with sand, it can be used as a seed compost. Seed compost is typically finer than other composts and contains fewer nutrients, to allow the seedlings to grow more easily.

Next month, we ’ll look at digging and preparing beds ready for planting in the spring. In the meantime, happy gardening!

Blackberry Time! Elizabeth Oliver

There is a special, single track lane near our house. It nestles under the ridge of the hill and is often the beginning, or the end, of a lovely dog walk or bike ride. To one side of the lane, fields drop away to a winding waterway that eventually runs through the village. On the higher side, the bank rises steeply and seems to tuck right under the escarpment. After the heart-pounding climb to the top of the lane, there is an informal crossroads; turn left and you can freewheel down another steep hill, turn right and the muddy farm-track might once more swallow your wellies. Straight ahead is an ancient green lane, with banks either side, which continues for a mile or more to an old coaching inn and the original post route.

During summer months the verges are filled with Wild Honeysuckle and Dog Roses, and tangled brambles. Today, the verges were full of glistening blackberries, signalling my favourite autumn job— picking the berries, and making bramble jelly.

I can’t quite remember when our family tradition started. It was certainly more than ten years ago that the children and I first scrambled up the bank to pick ripe berries in plastic ice-cream tubs. We would take them home to use some in blackberry and apple crumble, but most of the haul was cooked with a little water and hung in a muslin cloth to drip into the preserving pan overnight. Everybody knew not to disturb the precarious arrangement of muslin bag propped over pan— one false move and the whole lot would collapse, splashing the walls a vibrant shade of purple!

The children aren’t at home all the time now, so toast and jam for tea doesn’t happen quite as often. Still, I can’t resist the gentle rhythm of picking and preserving the blackberries to make sparkling jars of delicious bramble jelly. Bramble Jelly

Pick blackberries.

Put blackberries in a large saucepan or preserving pan, and add enough water to just about cover them.

Heat gently until all the fruit collapses.

Spoon the cooked blackberries into a muslin cloth or clean cotton tea towel, and secure into a bundle.

Hang the blackberry bundle above the clean saucepan/preserving pan, to collect the dripping juice. Leave overnight.

Measure the collected juice.

Add one pound of sugar for every pint of liquid. Also add the juice of one lemon.

Heat gently until the sugar is dissolved, then bring the liquid to a rolling boil.

The jelly is ready when wrinkles form on a small spoonful dropped onto a plate.

Ladle the hot jelly into clean, sterilized jars.

When the jars are cool, put them away in your cupboard, ready to conjure the last of summer on a cold winter’ s day.

Land and Language LearnGaelic

The highly informative LearnGaelic.Scot website tells us that Gaelic uses only 18 of the 26 letters found in English orthography. Moreover, in testimony to the close relationships Gaelic-speaking communities have held with the land, and the importance of trees and forests in Scotland— particularly in the Highlands and some of the Islands: Traditionally, each letter in Gaelic is named after a tree. These aren’t [now] used in everyday Gaelic [either] for names of trees or letters…

Nonetheless, herbologists, linguists and herbal folklorists may be interested to learn the traditional names of the Gaelic letters. To demonstrate the difference between these traditional names and modern Gaelic, some of the contemporary names for trees are also given below.

Letter Ailm Beith Coll Dair Eadha Feàrn Gort Uath Iogh Luis Muin Nuin Oir/Onn Peith bhog Ruis Suil Teine Ur Tree Elm/Fir Birch Hazel Oak Aspen Fern Gorse Hawthorn Yew Rowan Vine Ash Gorse Downy Birch Elder Willow Whin Heather Modern Gaelic

beithe/ craobh-bheithe calltainn/ craobh-challtainn darach/ craobh-dharaich

iubhar/ craobh-iubhair caorann/ craobh-chaorann

uinnseann/craobh-uinnsinn

In modern Gaelic, the names of the letters are sounded much as they are in English, unless the letter is carrying an accent (a stràc). To learn more about this beautiful language and its traditions, take a look at www.learngaelic.scot.