3 minute read

... And Equal in the Sight of Men?

To the Editor:

Attitudes toward minorities and behavioral norms have evolved in the county since more than a century ago. Remnants lurk while some persistent views are there for all to grasp if they simply admit their eyes and ears are accurately functioning.

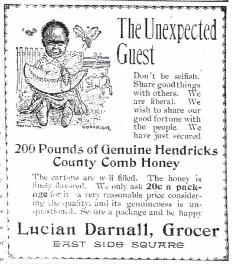

Advertisement

The generally accepted post-Civil War racial divide was obliquely expressed, perhaps due to innocent ignorance. Danville had not yet hosted Klan parades attracting crowds of 10,000.

It was commonplace to use demeaning language in referring to minorities. Perhaps no one white saw anything injurious about it.

Consider black-face minstrel shows, that American national entertainment. Or the term “coloreds,” and mockingly exaggerated dialects in making jokes.

Danville’s “burnt cork fraternity” provided two Masonic Hall “drawing room entertainments” just after Christmas 1870 to “large audiences, composed of our best citizens, who manifested their decided approval by unfeigned applause.”

“Jokes, songs and burlesques” included “delineations of the Fifteenth Amendmenters,” with dances and comedies “strikingly true, and which “exhibited a talent for Negro Minstrelsy.” That amendment, giving black men the right to vote, had been ratified earlier in 1870. Blacks presented minstrel acts, too. “The colored minstrel troupe consisting of local artists,” along with talent from Paris, Illinois, gave a show in January 1890.

Nonwhites were identified by their race. Danville Post Office regularly advertised unclaimed letters, and when one was for a black man in July 1882, “colored” appeared after his name.

The “colored folks’” basket meeting in July 1885 near Pecksburg, where Old Settlers sometimes met, drew around 1,500, but three-fourths were white. Everyone was welcome to those faith gatherings. Rev. Charles Roberts, Plainfield, also black, preached morning and afternoon.

In distant news, the paper reported in June 1885 that Henry O. Flipper, the first black West Point graduate, held a commission in the Mexican army, “and gets along very well with the ‘greasers.’” Little beyond his name was accurately reported.

The American Doves of Protection, “a colored organization,” picnicked at Lum Tout’s woods in August 1885. About 75 from Indianapolis and 50 from Danville and nearby, along with 100 whites gathered. After building a platform, the group enjoyed dancing and singing.

Come nightfall, the party moved to Danville’s skating rink, charging 15 cents for dancing. Whites were invited as spectators.

“However, but few of the better class were present, although a number of men and boys (mostly from the lower element) . . . conducted themselves in such a manner as to mar the pleasure of the colored folks and cause them to lose all interest in the amusement.”

Observing America is “a free country,” The Republican reproved, “if a white lady or gentleman choses to attend a colored dance . . . so long as the manager of the occasion does not object, there is no law to prevent them.”

Whites mixing socially with blacks was “not a crime,” but “a matter of taste,” the paper continued, “yet public opinion censures anyone who does so, and if the young man or woman does not respect the opinion of the public, they should not and can not expect the public to respect them.”

A “colored dance” at the rink three months later turned out well. “The tall and the short, the lean and the fat, the white and the black . . . all enjoyed a good time.”

When John Lee grew the largest turnip seen around town, 22 inches in circumference and weighing 4-3/4 pounds, it also was necessary in October 1885 to clarify that he was “colored.”

Societies, clubs and benefits could send $2 to Philadelphia in 1902 for a manuscript detailing everything needed to put on a successful minstrel show.

The Ladies’ Auxiliary of Danville’s Sons of Veterans entertained with a luncheon and minstrel show in June 1920. Ten ladies in plantation costumes and blackface sang, danced “and worked off jokes until there was danger of some one becoming hysterical when the curtain was considerately rung down.”

The Union’s Plainfield correspondent in October 1883, on Civil Rights, claimed the town’s black citizens “should feel proud that they can stand on equal footing with the white . . . they are free and equal in the eyes of the law.”

Not then. Not now. Paul Miner

Lizton