10 minute read

Unusually low tides.....................................................Pages

Photo by Melissa Renwick The tide is low on Mackenzie Beach, in Tofi no, on July 18. Drastic tidal changes in July have put more stress on sea life that live in the Pacifi c’s intertidal areas.

Unusually low water levels impact intertidal species

Advertisement

A close and full moon increased its gravitational pull on the ocean, resulting in an exaggerated tidal change

By Melissa Renwick Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Tofi no, BC - The west coast experienced some of its lowest tides of the year last week, leaving some intertidal animals vulnerable to the heat. A recent series of events lined up to trigger a “tidal phenomenon” that resulted in an exaggerated tidal range, according to Denny Sinnott, a DFO supervisor for Tides Current and Water Levels. First, the full moon on July 15 caused a gravitational pull on the ocean. Known as a spring tide, it occurs twice a month in conjunction with a new or full moon and contributes to the larger tidal range. The moon was also in perigee, meaning it was the closest to earth in its elliptical rotation around the earth, explained Sinnott. This, he said, added to the moon’s gravitational pull on the ocean. Tides were further impacted by the lunar nodal cycle, Sinnott added. In this 18.6-year cycle, the moon orbits around the earth on a 5-degree wobble. The wobble causes the lunar plane to align more closely to that of the earth’s, resulting in an even greater exaggeration of the tidal range, Sinnott said. Animals that live in intertidal environments are adapted to being dry and are able to withstand some temperature extremes caused by changing tides, explained DFO Biologist Sarah Dudas. But as global and sea water temperatures rise, Dudas said thermal stress is going to increase for these organisms. “If you have a really hot day, some of those animals are going to be on the edge of what they can tolerate,” she said. “It wouldn’t take much of a change to push them over into a temperature they can’t handle.” This was evident during last year’s unprecedented atmospheric heatwave, which broke over a dozen temperature records across the province. The village of Lytton shattered Canada’s all-time heat record, reaching 49.6 C on June 30 – a day before a wildfi re devastated much of the community. The heatwave, which was paired with a low tide, triggered a mass die-off of many diff erent species, according to University of British Columbia Professor Christopher Harley. Billions of animals perished from the heat, he said. “We always talk about climate change in a future tense,” said Harley. “But I think we can start talking about it in the present tense, and even the past tense.” The United Kingdom is currently facing similar temperature extremes, leading to fi res breaking out across London. “We’re in a period of major awakening of climate change eff ects,” Harley said. “The weather is playing by diff erent rules and we don’t understand those rules very well.” To document how extensive the die-off was, Harley visited many diff erent sites along B.C.’s coast last summer and said it was like “walking in on some murder scene and just trying to tally the dead.” “I would get out of the car and could smell the shore,” he said. “I could smell the death before I got down there.” Animals live in diff erent layers within intertidal environments, Harley said. Without tides, he said many species wouldn’t exist because they’d get eaten or become overgrown. “The tides actually generate diversity,” he said. It’s largely the timing of the tides that impact animals living in intertidal zones. In places like Tofi no, Harley said low tide in the summer is generally in the morning. Whereas places like Victoria and Vancouver experience low tide around noon – during the hottest time of the day, he said. “We already have less diversity in places like Victoria than we do in places like Tofi no,” said Harley. “And it’s going to become more stark as we start to lose additional species that can no longer survive in Victoria or Vancouver.” Ucluelet Aquarium Curator Laura Griffi th-Cochrane said the low tides allowed her to access areas that are usually wave-impact zones, which are commonly too dangerous to explore. “It’s really important to know how everything is doing,” she said. “There’s a lot of intertidal species that can be good indicators of the overall ecosystem health.” As ocean water temperatures increase, Griffi th-Cochrane said dissolved oxygen levels decrease – which has placed additional stress on many species. “It’s going to be harder for the species that we’re hoping to build back to [recover] with all of these extra stresses,” she said. Using a catch-and-release model, the Ucluelet Aquarium returns to the same sites every year to collect animals. This allows the aquarium to compare how easy it is to fi nd certain species compared to previous years, while observing which species are prolifi c, versus those that are disappearing altogether. Griffi th-Cochrane said the aquarium decided not to collect any squat lobster, side-stripe shrimp or spot prawns this summer. “We’ve seen temperatures trend towards hotter and hotter every summer and they really like to have more stable, cool temperatures,” she said. “There are some species we might not be able to display for a while.” During last week’s low tide event, Dudas was working on an intertidal biodiversity survey on Gabriola Island, where she noticed a lot of mussels had recently died. Passersby told Dudas the beach didn’t normally smell so bad. “It smells bad because things have recently died,” she said. “They’re decomposing. That bad smell is coming from the mussel bed.” Darker coloured animals, such as mussels, are going to “bear the brunt of a really sunny, super-low tide more so than barnacles that are white,” she said. These changing conditions are generally happening at a faster rate than animals can evolve or adapt to, Dudas said. “We’re going to see more mortality as stress on these organisms increase,” she said. On June 20, the province announced a strategy supported by $513 million to ensure B.C. is prepared for climate impacts in the near future. It includes an expanded role for the BC Wildfi re Service to provide enhanced wildfi re prevention and an extreme heat preparedness plan to help keep communities safe during heat waves. Despite that, Harley said the public needs to continue applying pressure on the government to make the “big changes we need” to move from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. “We haven’t been super successful with that and it’s going to take a while,” he said. In the meantime, Harley said there are shorter-term solutions, such as local conservation, that can help keep species alive. “Taking these changes seriously and beginning to plan around temperature changes and extreme events is really important,” said Griffi th-Cochrane. “We need to look at our industries and our practices and make changes so that we aren’t continuing to damage the environments that support us.”

More than 100 relatives and supporters fi lled Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s House of Unity to hold up Ray Williams

By Eric Plummer Ha-Shilth-Sa Editor

Tsaxana, BC - While Canada struggles to come to terms with its colonial past, the life of Ray Williams serves as a critical reminder of the old world that rapid development took for granted – and what teachings should be preserved for future generations. As the patriarch of the last family to remain in Yuquot, the ancestral home of the Mowachaht tribe on the southern tip of Nootka Island, the Williams family still hunt and eat seal. Ray recalls the trick of using the ocean’s horizon line as a guide while leveling a window frame on his house. When aligned correctly from the certain spots on the ocean, mountain peaks serve as markers for the best fi shing spots in the area, an old trick Ray learned from his forefathers. “The landmark is marked by the top of a mountain,” he said while sitting in his home one rainy morning in May. “My boys know it now…we still use it today.” In the interest of moving the community to an area less isolated from the rest of the province, in the late 1960s the government began relocating members of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation from Yuquot to a reserve on the shore of Muchalaht Inlet, south of Gold River. The Nootka Island community gradually thinned out as families took off ers to move to a more modern environment. But Ray’s family never left, eventually becoming the last to reside in the village where archaeological excavations have uncovered evidence showing 4,300 years of human habitation.

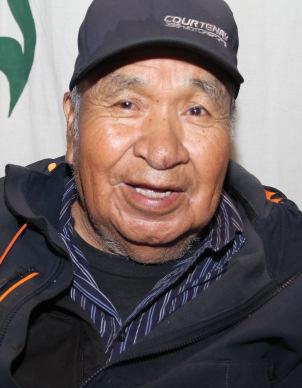

Ray Williams As a small child Ray was taken from Yuquot to attend Christie Indian Residential School. As an adult he wasn’t willing to trust what the Canadian government was proposing, even if the repeated off ers eventually entailed a new house for his family. “Oh, my goodness, they were tempting,” said Ray of the off ers to relocate. “I said no again. ‘No, I want to stay here.’” Now at the age of 80 with failing eyesight, Ray sees more support from people knowing that he will never leave Yuquot, recognizing the importance of his family remaining in the village amid the transformational changes of the last 50 years. “My uncle is the last sibling of all his brothers and sisters,” said Ray’s niece, Marge Amos. “The teachings and the values aren’t gone. It’s up to us to carry them forward.” After more than two years of living under the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, family members believed it was time to celebrate the life Ray has lived. On Saturday, July 16 a gathering was

Photos by Eric Plummer Dancers (above) fi lled the fl oor before a crowd in the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation’s House of Unity in Tsaxana on July 16. More than 100 were fed at the event, which honoured the life of Ray Williams, who is the youngest of 15 siblings.

held in Tsaxana, fi lling the Mowachaht/ Muchalaht First Nation’s House of Unity. “It was a total surprise. Nobody was to leak it out to him,” said Amos, mentioning a story Ray’s son told him related to the upcoming occasion of Pope Francis visiting Canada. “Darrell told him that it has to do with the Pope.” After being brought down Muchalaht Inlet to the First Nation’s community by Gold River, Ray had no idea what was waiting for him. “We had him walk into the hall, and we were all standing there waiting for him. They sang a song as he walked in, and he started crying. He hadn’t seen some of the family for three, four years.” “It’s like a celebration of life, to recognize him as a humble man, because of the things he’s done in his life, now we want to share that through wisdom and through knowledge,” said Ray’s nephew, Paul Lucas, who came from Hot Springs Cove for the event. “We are here today to appreciate who he is, not what he is. A humble man.” The big house vibrated with singing and drumming, as the fl oor fi lled with dancers. Speeches fi lled the afternoon and evening with acknowledgments of family connections. “I want to thank our uncle for taking care of Yuquot,” said Brian Lucas Sr. before the crowd. “He’s important.” With a strong tradition of relying on large gatherings to practice ancestral culture and fortify family ties, the COVID-19 pandemic and it’s related social restrictions were particularly hard on Nuu-chah-nulth communities. Although Ray was never alone, Yuquot was often quiet. During this period Terri Williams passed away in the fall of 2020, Ray’s partner of almost 60 years. “You’re still here because you have a reason to be here,” said Amos, thinking of her uncle. “Everyone you see in this hall tonight were going through lots through the COVID. A lot of them needed that uplifting. One of the things the old people say is, ‘You never fear sickness, you never be scared of it, because if you get scared of it, you’re going to attract it.’ You always know you’re going to be okay.” “Respect yourself so you can respect others,” added Lucas. “So I come here today to show my respect to my uncle.” With his relatives surrounding him, Ray was overcome with emotion. “Oh, what a surprise, I felt like a king,” he said. “It’s a lot better than winning a million dollars.”