28 minute read

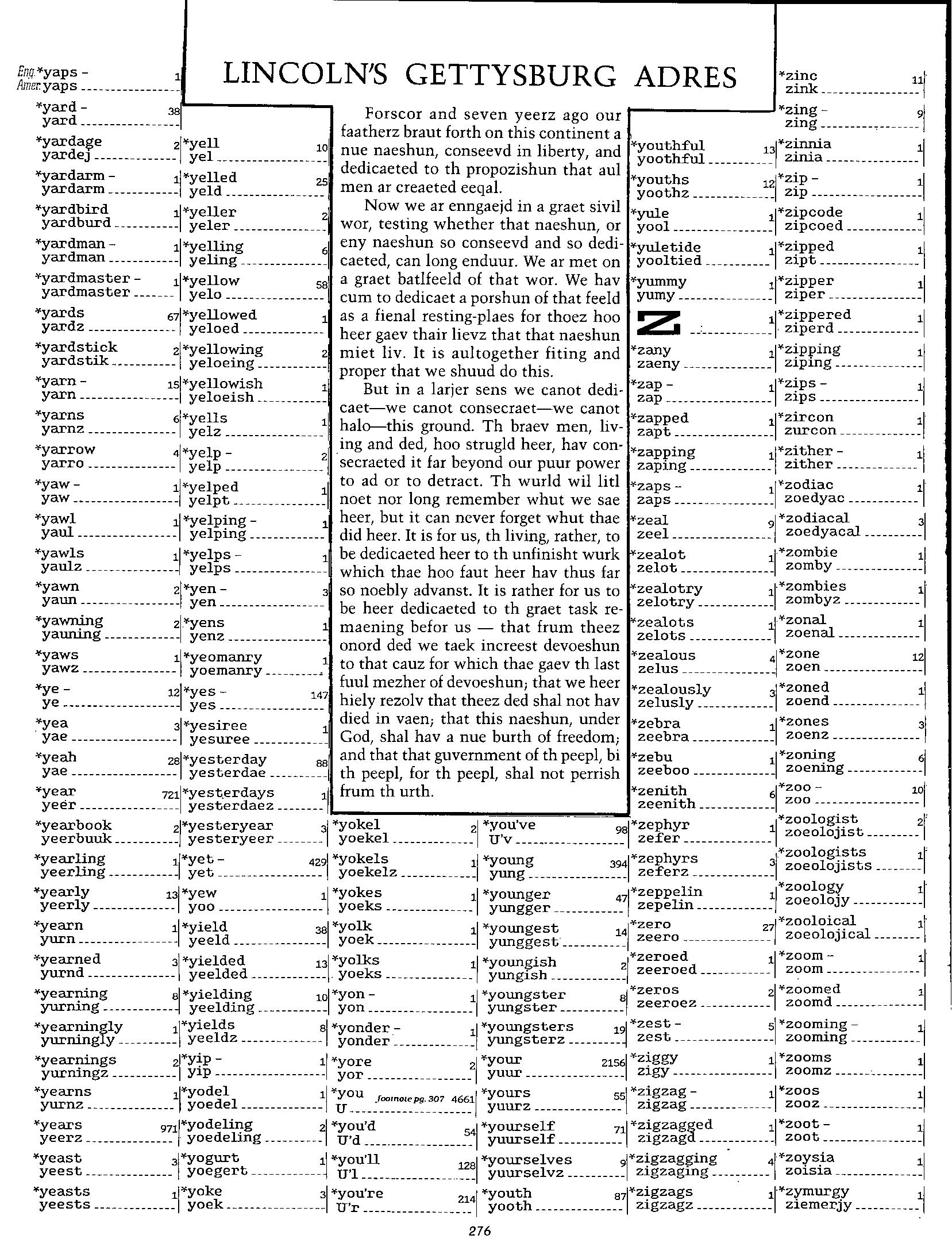

LINCOLN'S GETTYSBURG ADRES

*yard Forscor and seven yeerz ago our yardage faatherz braut forth on this continent a -2J"Ye10 nuenaeshun, conseevd in liberty, and -i32frda1 "yardarm yelled 25 dedicaeted to th propozishun that aul *youths 2"zip -yardarm ------------ - yeld ------------------men ar creaeted eeqal. yoothz ---------------zip 1 ir "yardbd 1 "yeller 2 Now we at enngaejd in a grater sivil "yule "zipoode yardburd ------------yeler -----------------wor, testing whether that naeshun, or yool -----------------1 zipcoed 1 "yardman - 1 "yelling 6 eny naeshun so conseevd and so dedi- "yuletide 1"zippedyardman -------------yeling -----------------caeted, can long enduur. Wear met on yooltied ------------zipt 1 "yardmaster - i"yellow 58 a graet batifeeld of that wor. We hay "yummy 1"zipper 1yardmaster --------yelo ------------------cum to dedicaet a porshun of that feeld yimy -----------------ziper ................ "yards 67 "yellowed 1 as a fienal resting-plaes for thoez boo yardz --------------- - yeloed -------------- beergaev thair lievz that that naeshun 1 "pped ziperd 1 "yardstick a"yellowingyardstik ------------yeloeing 2 miet liv. It is aultogether fiting and *zany 1"zippingzaeny ----------------zipingproper that we shuud do this. 1 " 1 But in a larjer sens we canot dedi- caet—we canot consecraet—we canotyarns c"yells 1 "zapped 1"zircon yarnz ---------------yelz ------------------halo—this ground. Th braev men, liv- zapt ----------------- - zurcon "yarrow 4"yelp 2 ing and ded, hoo strugld beer, ha y con- "zapping 1 -

"zither yarro ---------------yelp -------------------secraeted it far beyond our poor power zaping -------------- zither 1 "yaw- i"yelpedYaw -------------------yelpt --------------1 to ad or to detract. Th world wil litl "zaps 1"zodiac - --noet nor long remember whut we sae zaps -----------------zoedyac "yawl i "yelping 1 heer, but it can never forget whut iliac "zeal "zodiacal yaul ----------------- - yelping --------------did beer. It is for us, th living, rather, to zeel ----------------- - zoedyacal 3 "yawls i "yelps — i be dedicaeted heer to th unfinisht work "zealot 1"zombie yaulz ---------------- - yelps -----------------which thae hoo lam -heer hay thus far zelot ----------------zomby "yawn 2- "yen —yaun -----------------yen "a so noebly advanst. It is rather for us to "zealotry be beer dedicaeted to th graet task re- zelotrv i maening befor us — that frum theez z1ts 1"zombies zombyz -al I S i"yeoinanry onord ded we tack increest devoeshun to that cauz for which thae gaev th last i2 "ye — 12 "yesYe ---------------------yes ----------------' foul mezher of devoeshun; that we beer "zealously 3 "zoned hiely rezolv that theez ded shal not hay zelusly --------------zoend 1 "yea 3 "yesiree died in vaen; that this naeshun, under "zebra 1 "zones yae ------------------ - yesuree ------------ God, shal hay a nue burth of freedom; zeebra ---------------zoenz 3 "yeah 28 "yesterday and that that government of th peepl, bi "zebu "zoning 6 yae -------------------yesterdae ------------th peepl, for th peepi, shal not perrish zeeboo ---------------zoemng "year 721"yesZerdays yeer -----------------yesterdaez i from th urth. "zerdth zeenth ----------------10 -----------------"yearbook 2"yesteryear 31 "yokel 2 "you've "zephyryeerbuuk -----------yesteryeer --- ----- - yoekel --------------us' --------------------zefer --------------- 2F "yearling i "yet — 429 1 ''yokels i-- "young 394 "zephyrs yeerling ------------ - yet ------------------yoekelz ------------yung ----------------- - zeferz --------------3g-r:55 ii "yearly 13- "yew i "yokes i "younger 47"zeppeiin yeerly --------------yoo -------------------yoeks --------------- - yungger -------------zepelin -------------------jy -----------"yearn 1 "yield 38 "yolk 1 "youngest 14 zero 27 zool1i9l ii yurn -----------------yeeld -----------------yoek ----------------- - yunggest ---------- -

Advertisement

-zeero --------------- -zoeo OJ1Cal "yearned a "yielded 13 "yolks 1 "youngish yurnd --------------- - yeelded ---------------yoeks --------------- - yungish -----------2 "zeroed 1 "zoOm - - zeeroed ------------ - zoom 1 "yearning ekyielding io "yon 1 "youngster "zeros 2 'zoomed yurning ------------ yeelding -------------yon ------------------ - yungster ----------- - zeeroez -------------zoomd i "yearningly "yields a *Yonder-"youngsters 191"zest s "zooming — yurningly ---------- - yeeldz ---------------yonder -------- ----- -yungsterz --------- - zest -----------------zoonung 1 "yearnings 2"yip — 1 "yore 2 -- "your 2156 ziggy i "zooms yurningz ----------- - yip -------------------yor -----------------yuur ------------------zigy ----------------- - zoomz 1 "yearns 1"yodel 1 you footnote pg 307 4661 yours 'zigzag --"zoos yurnz ----------------yoedel ---------------u ----------------------yuurz ----------------zigzag -------------zooz 1 "years 971"yodeliig 2 "you'd "yourself 71 "zigzagged "zoot — yeerz -----------------yoedeling ---------- -u'd --------------------yuurself ----------- - zigzagct --------------zoot "yeast 3"yogurt yeest ----------------yoegert ------------ij "you'll 128- yourseli'es 9"zigzagging 4"zoysia -1 ml ---------------------yuurselvz ----------zigzaging ---------- - zoisia 1 "yeasts 1"yoke 3 "you're yeests -------------- - yoek ------------------U'r ------------- 2i4 "youth 87"zigzags 1"zymurgy ------yooth ----------------zigzagz ------------- - ziemerjy 276

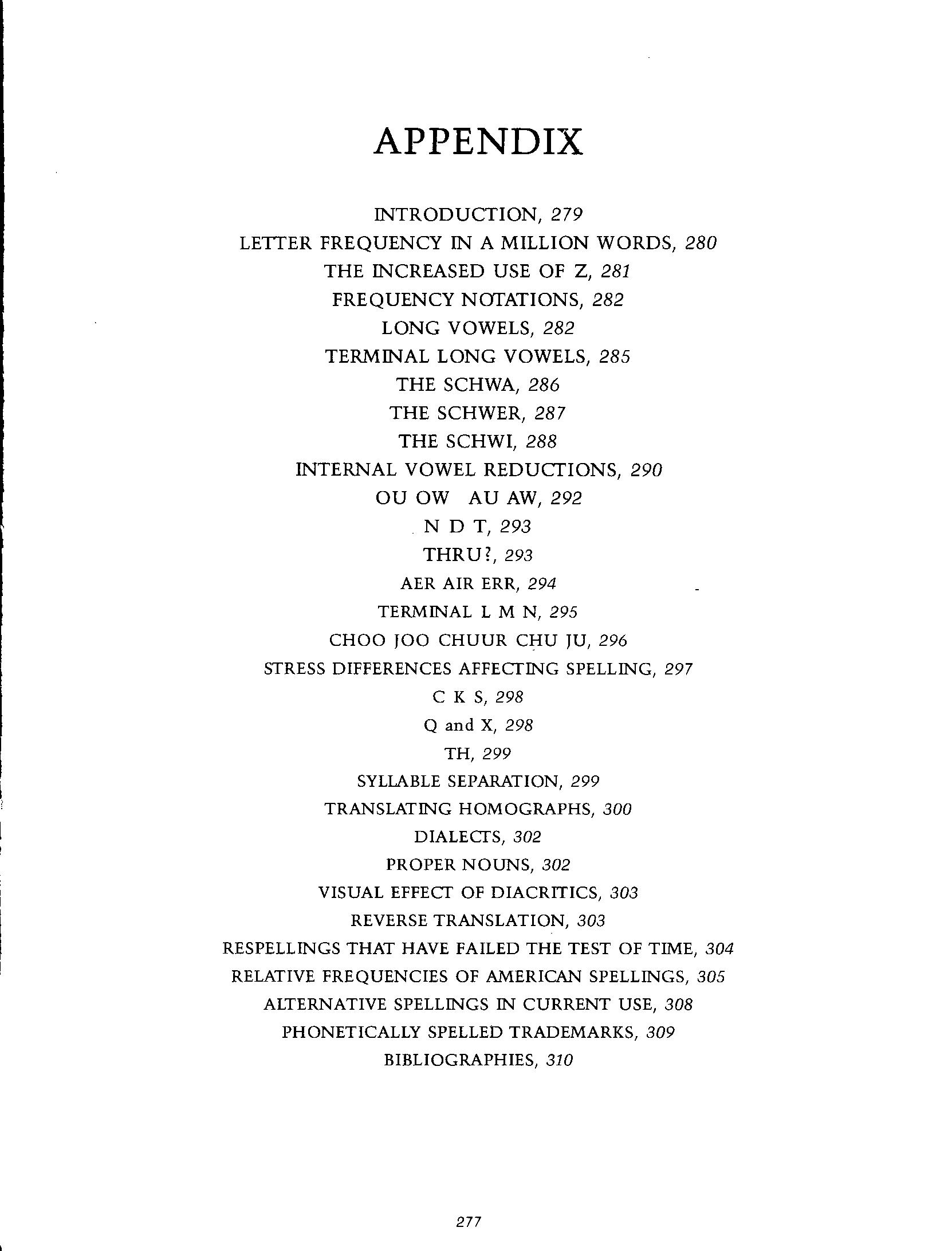

APPENDIX

INTRODUCTION, 279 LETTER FREQUENCY IN A MILLION WORDS, 280 THE INCREASED USE OF Z, 281 FREQUENCY NOTATIONS, 282 LONG VOWELS, 282 TERMINAL LONG VOWELS, 285 THE SCHWA, 286 THE SCHWER, 287 THE SCHWI, 288 INTERNAL VOWEL REDUCTIONS, 290 OU OW AU AW, 292 NDT,293 THRU?, 293

AER AIR ERR, 294 TERMINAL L M N, 295 CHOO JOO CHUUR CHU JU, 296 STRESS DIFFERENCES AFFECTING SPELLING, 297 C K 5, 298 Q and X, 298 TH, 299 SYLLABLE SEPARATION, 299 TRANSLATING HOMOGRAPHS, 300 DIALECTS, 302 PROPER NOUNS, 302 VISUAL EFFECT OF DIACRITICS, 303 REVERSE TRANSLATION, 303 RESPELLINGS THAT HAVE FAILED THE TEST OF TIME, 304 RELATIVE FREQUENCIES OF AMERICAN SPELLINGS, 305 ALTERNATIVE SPELLINGS IN CURRENT USE, 308 PHONETICALLY SPELLED TRADEMARKS, 309 BIBLIOGRAPHIES, 310

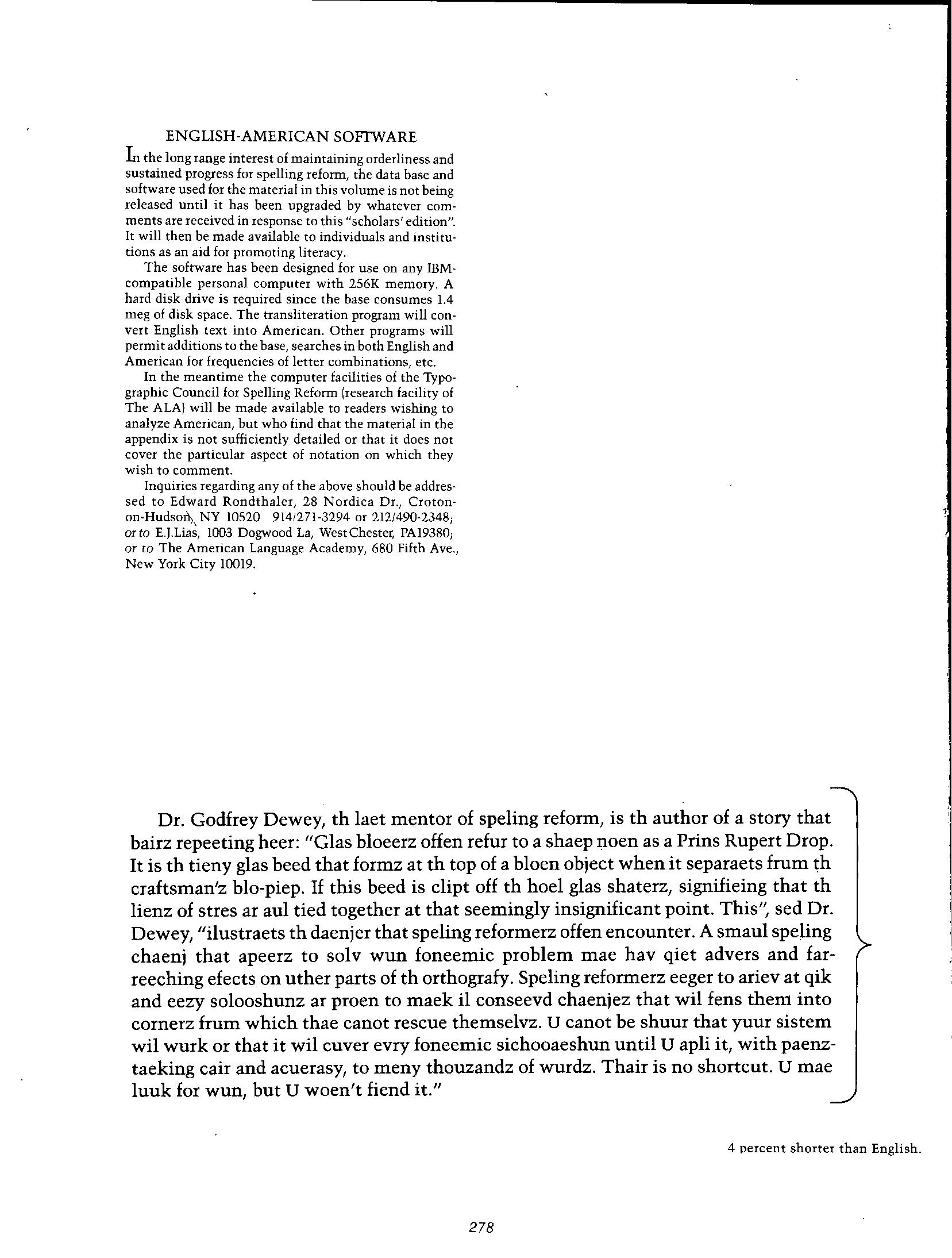

ENGLISH-AMERICAN SOFrWARE L the long range interest of maintaining orderliness and sustained progress for spelling reform, the data base and software used for the material in this volume is not being released until it has been upgraded by whatever comments are received in response to this "scholars' edition". It will then be made available to individuals and institutions as an aid for promoting literacy.

The software has been designed for use on any IBMcompatible personal computer with 256K memory. A hard disk drive is required since the base consumes 1.4 meg of disk space. The transliteration program will convert English text into American. Other programs will permit additions to the base, searches in both English and American for frequencies of letter combinations, etc.

In the meantime the computer facilities of the Typographic Council for Spelling Reform research facility of The ALA) will be made available to readers wishing to analyze American, but who find that the material in the appendix is not sufficiently detailed or that it does not cover the particular aspect of notation on which they wish to comment.

Inquiries regarding any of the above should be addressed to Edward Rondthaler, 28 Nordica Dr., Crotonon-Hudsoñ) NY 10520 914)271-3294 or 212/490-2348; orto E.J.Lias, 1003 Dogwood La, WestChester, PA19380; or to The American Language Academy, 680 Fifth Ave., New York City 10019.

Dr. Godfrey Dewey, th laet mentor of speling reform, is th author of a story that bairz repeeting beer: "Glas bloeerz offen refur to a shaep noen as a Prins Rupert Drop. It is th tieny glas heed that formz at th top of a bloen object when it separaets frum th craftsman'z blo-piep. If this beed is clipt off th hoel glas shaterz, signifieing that th lienz of stres ar aul tied together at that seemingly insignificant point. This"ç sed Dr. Dewey, "ilustraets th daenjer that speling reformerz offen encounter. A smaul speling chaenj that apeerz to solv wun foneemic problem mae hay qiet advers and farreeching efects on uther parts of th orthografy. Speling ref ormerz eeger to ariev at qik and eezy solooshunz ar proen to maek il conseevd chaenjez that wil fens them into cornerz fnim which thae canot rescue themselvz. U canot be shuur that yuur sistem wil wurk or that it wil cuver evry foneemic sichooaeshun until U apli it, with paenztaeking cair and acuerasy, to meny thouzandz of wurdz. Thair is no shortcut. U mae luuk for wun, but U woen't fiend it."

4 percent shorter than English.

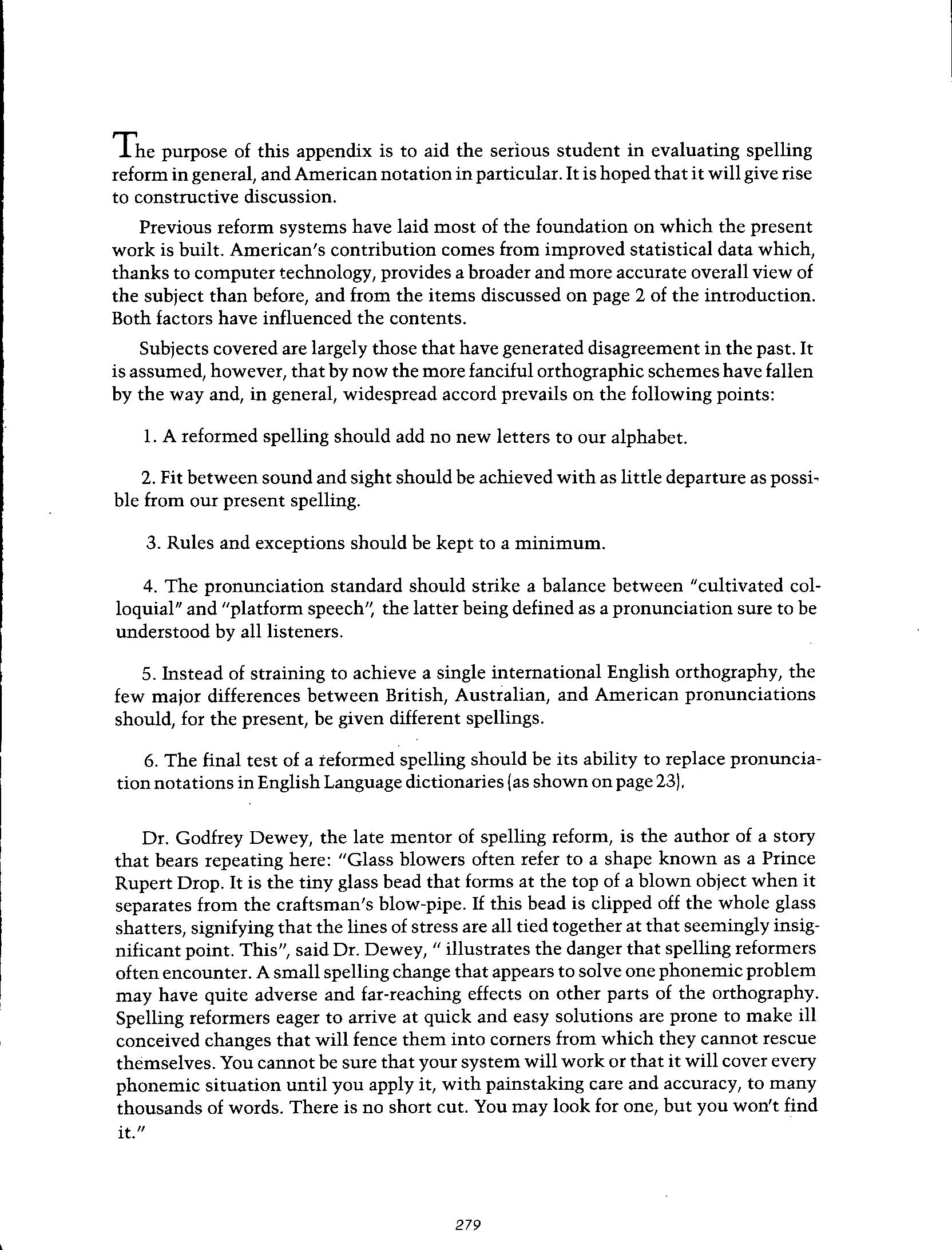

The purpose of this appendix is to aid the serious student in evaluating spelling reform in general, and American notation in particular. It is hoped that it will give rise to constructive discussion.

Previous reform systems have laid most of the foundation on which the present work is built. American's contribution comes from improved statistical data which, thanks to computer technology, provides a broader and more accurate overall view of the subject than before, and from the items discussed on page 2 of the introduction. Both factors have influenced the contents.

Subjects covered are largely those that have generated disagreement in the past. It is assumed, however, that by now the more fanciful orthographic schemes have fallen by the way and, in general, widespread accord prevails on the following points:

1. A reformed spelling should add no new letters to our alphabet.

2. Fit between sound and sight should be achieved with as little departure as possible from our present spelling.

3. Rules and exceptions should be kept to a minimum.

4. The pronunciation standard should strike a balance between "cultivated colloquial" and "platform speech", the latter being defined as a pronunciation sure to be understood by all listeners.

5. Instead of straining to achieve a single international English orthography, the few major differences between British, Australian, and American pronunciations should, for the present, be given different spellings.

6. The final test of a reformed spelling should be its ability to replace pronunciation notations in English Language dictionaries (as shown on page 23).

Dr. Godfrey Dewey, the late mentor of spelling reform, is the author of a story that bears repeating here: "Glass blowers often refer to a shape known as a Prince Rupert Drop. It is the tiny glass bead that forms at the top of a blown object when it separates from the craftsman's blow-pipe. If this bead is clipped off the whole glass shatters, signifying that the lines of stress are all tied together at that seemingly insignificant point. This", said Dr. Dewey, "illustrates the danger that spelling reformers often encounter. A small spelling change that appears to solve one phonemic problem may have quite adverse and far-reaching effects on other parts of the orthography. Spelling reformers eager to arrive at quick and easy solutions are prone to make ill conceived changes that will fence them into corners from which they cannot rescue themselves. You cannot be sure that your system will work or that it will cover every phonemic situation until you apply it, with painstaking care and accuracy, to many thousands of words. There is no short cut. You may look for one, but you won't find it."

FREQUENCY OF EACH LETTER IN A MILLION WORDS

600,000 letters per 600,000

A B C D E F G H I JKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

ENGLISH AMERICAN

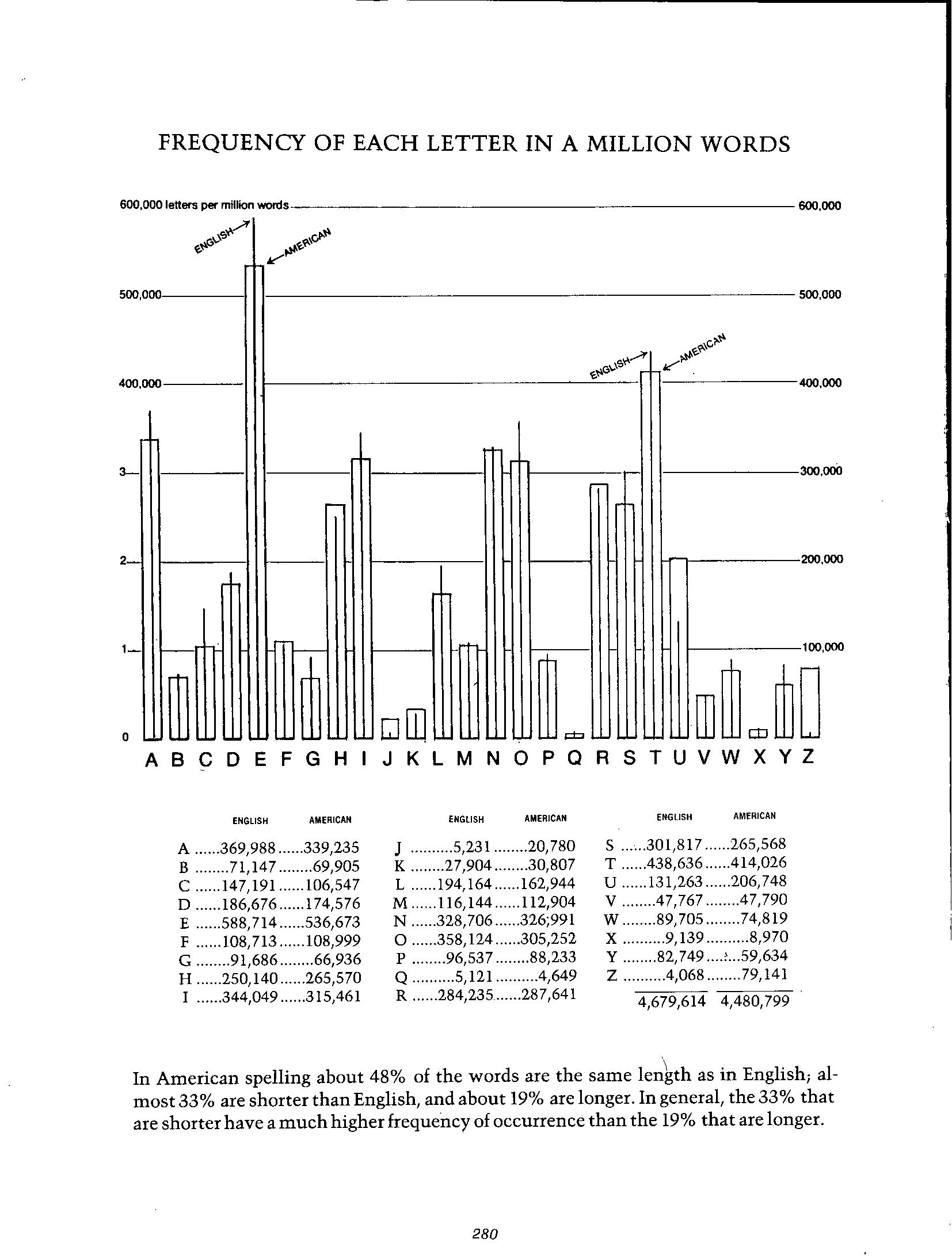

A ..... .369,988 ..... .339,235 B ....... . 71,147 ....... . 69,905 C ..... . 147,191 ..... . 106,547 D ..... . 186,676 ..... . 174,576 E ..... . 588,714 ..... .536,673 F ..... . 108,713 ..... . 108,999 C ....... . 91,686 ....... . 66,936 H ..... .250,140 ..... . 265,570 I ..... .344,049 ..... . 315,461

ENGLISH AMERICAN

J ......... . 5,231 ....... K ....... .27,904 ....... . . 20,780 30,807 L ..... . 194,164 ..... . 162,944 M ..... . 116,144 ..... . 112,904 N ..... .328,706 ..... .326;991 0 ..... .358,124 ..... .305,252 P ....... .96,537 ....... . 88,233 Q ......... . 5,121 ......... .4,649 R ..... . 284,235 ..... . 287,641

ENGLISH AMERICAN

S ..... . 301,817 ..... .265,568 T ..... .438,636 ..... . 414,026 U ..... . 131,263 ..... . 206,748 V ....... .47,767 ....... . 47,790 W ....... . 89,705 ....... . 74,819 X ......... . 9,139 ......... .8,970 Y ....... . 82,749 Z ......... . 4,068 ....... . 79,141 4,679,614 4,480,799

In American spelling about 48% of the words are the same length as in English; almost 33% are shorter than English, and about 19% are longer. In general, the 33% that are shorter have a much higher frequency of occurrence than the 19% that are longer.

Length of average word in English......... . 4.68 letters Length of averej wurd in American.... . 4.48 leterz American saves an average of 2 letters in 10 words. American saevz an averej of 2 leterz in 10 wurdz.

When all frequencies are added together American spelling is 4 1/4 percent shorter than English spelling. This saving, however, does not take into account the spaces between words. When the keystrokes for spaces are added the net saving is about 3 1/2 percent, or several pages in an average book.

American spelling substantially decreases the frequency of 12 letters; has little or no effect on 11; and significantly increases j, u, and z. In English the j-sound is usually represented —misrepresented -by g (general vs jeneral; geography vs jeografy). The z-sound - common in our spoken language - is almost always represented by s (possessions vs. pozeshunz). The greater frequency of u comes in part from the introduction of the new digraph uu to relieve oo of its double-duty role in traditional English spelling as illustrated by the word 'footstool' (respelled 'fuutstool' in American).

Replacing the illogical uses of g, s, and oo with letters accurately representing the spoken sounds will have a noticeable effect on the printed page. J and uu will appear once in every five or six lines of ordinary text, and every ten or twelve lines of a newspaper. Z, the rarest of all letters in English spelling but far from rare in our speech, will appear once in every line or two - slightly less than y now appears in English spelling.

THE INCREASED USE OF Z

We use the s-sound in speech for somewhat less than half of our plurals and third person singulars (hits, keeps, tonics, surfs, tasks). These will continue to be written with s in American. The remainder are spoken with a z-sound (armz, jabz, yardz, kegz, cowz, jawz) and would be written accordingly. It is often assumed that we presently spell our plurals in only one way. That is not the case. We spell them in four different ways: s, ies, es, ses (boy boy[sJ, country countrJe4 church church[esj, bus busjes]). The proposed use of s and z reduces these four tothree (s, z, ez). It also eliminates irregularities. The suggestion has been made that plurals and third person singulars continue to be written with s or es regardless of sound. This overlooks the role of z in providing clear distinction between such words as 'loos looz, flees fleez, cors corz, hous houz, does cloez, purs purz, pees peez, peers peerz, scairs scairz, fauls faulz, hens henz, etc. Context might be relied on to overcome confusion, but it is hardly good practice to depend on context when a clearer means is available.

Perhaps the best way to effect substantial reduction in z-frequency is to retain the traditional spelling of five very high frequency words: is, was, as, his, has (rather than respelling them iz, wuz, az, hiz, haz). These have a combined frequency of 38,960 per million words. By continuing the use of s in these five spellings the letter z will appear on the page only 65 percent as often as we hear it in speech. This concession to tradition is observed in American, and all frequency tabulations take it into account.

FREQUENCY NOTATIONS

Frequencies can be very helpful in selecting the best of several possible spellings. When we know how often a particular grapheme - a letter or a digraph - will appear on the printed page, we are in a good position to judge its overall visual impact. For this purpose numerical notations such as 649:9270 will be found in the text. They serve to put the item under consideration into correct perspective. The meaning of a notation like 649:9270 is: "The grapheme illustrated in the preceding word or words occurs in 649 different words having a combined frequency of 9270 occurrences per million words of running text." (The fact that the same grapheme may appear more than once in the same word has, of course, been taken into account.)

Sometimes the frequencies are given in terms of occurrences per page. Such estimates are based on the assumption that a single-spaced typewritten page and most book pages contain between 400 and 500 words. It is helpful to remember that frequencies under 10,000 will appear fewer than 4 or 5 times on an average page. This is a very good rule-of-thumb to keep in mind when considering the general impact of a particular spelling.

LONG VOWELS

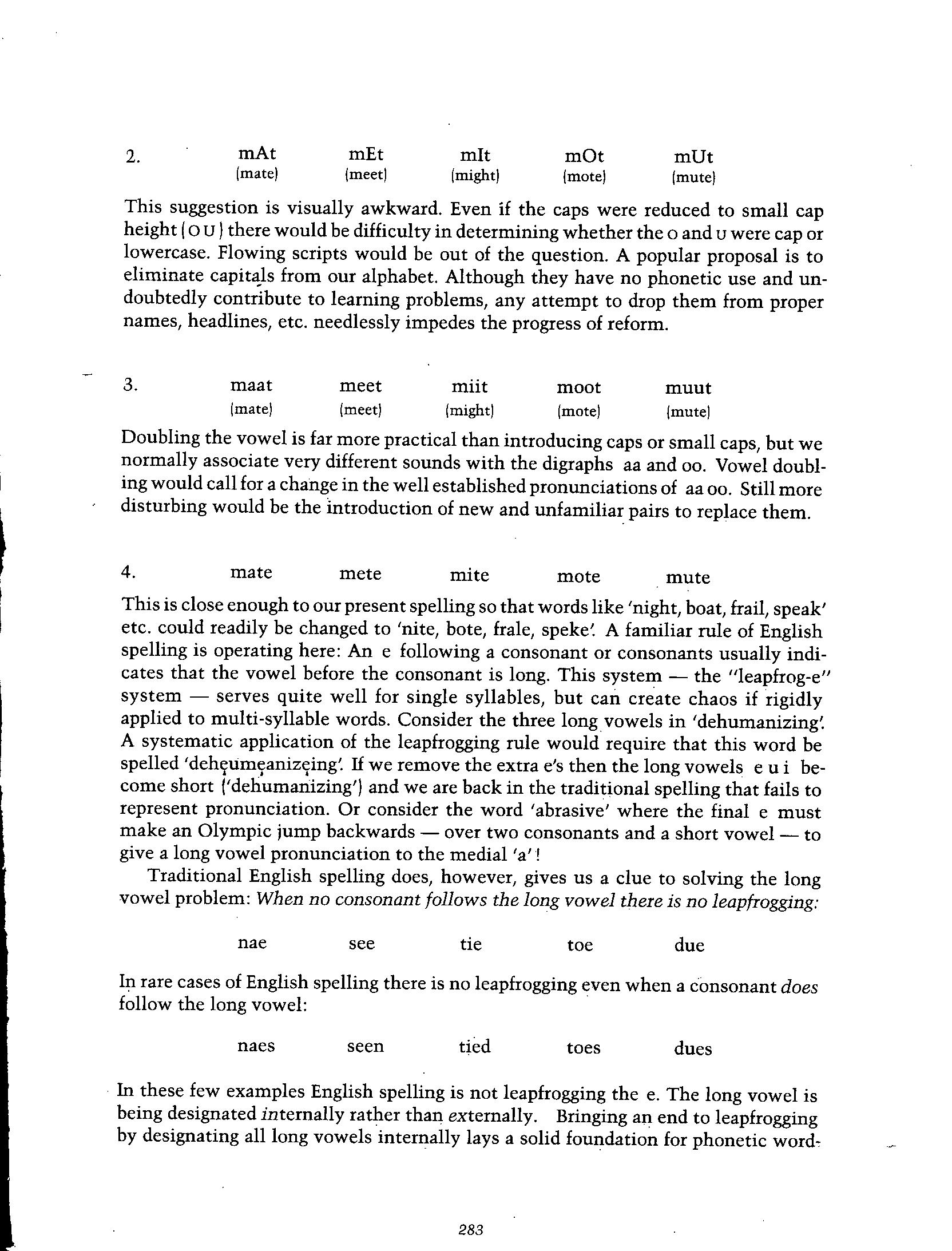

In English spelling we use the short vowels and their diluted schwas far more often than the long vowels. The ratio is about 4 to 1. It is appropriate, then, that the single letters a e i o u should represent the short vowels and their schwa dilutions. The ever-present problem facing all reformers is the knotty one of finding the best way to modify a e i o u so that these five letters may also represent the five long vowels. Here are some suggestions that have been proposed

mat met mit möt mt

(mate) (meet) (might) (mote) (mute)

ha he hi ho

(hay) (he) (high) (hoe) (hue)

A macron above (or below) the long vowel has much to commend it. It is clear and simple. It would reduce the number of letters in a million American words from about 4,480,000 to about 4,340,000— a reduction ratio of almost 100 to 97—saving perhaps ten pages in an average book. Use of the macron in handwriting or as it becomes available in typewriting and printing may be desirable. Anything that increases our vowel symbols should not be ruled out. But diacritics, particularly in the early stages of reform, are not psychologically welcome or mechanically simple. They would seriously reduce the visual compatibility with traditional spelling by giving many of our words a foreign cast. Major and very costly alterations of keyboards for typewriters, computers, and typesetting machines would be required. The reform movement does not need another hurdle in its path, at least not at this point. Introduction of a diacritic would be less disruptive than adding new letters, but on a smaller scale it presents some of the same problems.

2. mAt mEt mIt mot mUt

(mate) (meet) (might) (mote) (mute) This suggestion is visually awkward. Even if the caps were reduced to small cap height (o u) there would be difficulty in determining whether the o and u were cap or lowercase. Flowing scripts would be out of the question. A popular proposal is to eliminate capitals from our alphabet. Although they have no phonetic use and undoubtedly contribute to learning problems, any attempt to drop them from proper names, headlines, etc. needlessly impedes the progress of reform.

3. maat meet miit moot muut

(mate) (meet) (might) (mote) (mute) Doubling the vowel is far more practical than introducing caps or small caps, but we normally associate very different sounds with the digraphs aa and oo. Vowel doubling would call for a change in the well established pronunciations of aa 00. Still more disturbing would be the introduction of new and unfamiliar pairs to replace them.

mate mete mite mote mute This is close enough to our present spelling so that words like 'night, boat, frail, speak' etc. could readily be changed to 'nite, bote, frale, speke'. A familiar rule of English spelling is operating here: An e following a consonant or consonants usually indicates that the vowel before the consonant is long. This system - the "leapfrog-e" system - serves quite well for single syllables, but can create chaos if rigidly applied to multi-syllable words. Consider the three long vowels in 'dehumanizing': A systematic application of the leapfrogging rule would require that this word be spelled 'dehçumeanizçing': If we remove the extra e's then the long vowels e u i become short ('dehumanizing') and we are back in the traditional spelling that fails to represent pronunciation. Or consider the word 'abrasive' where the final e must make an Olympic jump backwards - over two consonants and a short vowel - to give a long vowel pronunciation to the medial 'a'

Traditional English spelling does, however, gives us a clue to solving the long vowel problem: When no consonant follows the long vowel there is no leapfrogging:

nae see tie toe due

In rare cases of English spelling there is no leapfrogging even when a consonant does follow the long vowel: naes seen tied toes dues

In these few examples English spelling is not leapfrogging the e. The long vowel is being designated internally rather than externally. Bringing an end to leapfrogging by designating all long vowels internally lays a solid foundation for phonetic word-

building - a principle advocated by Ripman, Dewey and Pitman, and supported by many today. It is this principle that is used in American spelling:

maet meet miet moet muet maeted meets miety moets muetly maetles meeting mietyest moetiv muetabl

6281:63,174 3810:51,130 4440:43,116 3452:35,172 1870:21,031

It is worth noting that the use of the letter e to change the pronunciation of a preceding vowel is not unique to English. In German, for example, a trailing e. often serves as an alternative for a diacritic in words such as: Blute Bluete; Schonheit Schoenheit; Arger Aerger, etc. This is seen as a perfectly natural and comfortable role for e

5. Consideration should probably be given to the possibility of selecting a more familiar notation for long-a, even though this runs counter to the logic of adding the suffix 'e' to denote a long vowel, as recommended by earlier reformers and generally looked upon with favor today. While the digraphs 'ee, ie, oe, ue' occur frequently enough in English spelling to be recognized easily by present readers, it must be said that 'ae' lacks an equal familiarity. Although one may soon become accustomed to 'ae', there is merit in at least considering a more familiar notation. The digraphs"ay' (play), or 'ai' (main) are obvious candidates. Both 'ay' and 'ai' account for about 13% of long-a spellings in English.

Caution warns us that ambiguities or conflicts with surrounding letters could arise. They do indeed arise in the case of 'ai' which is subject to possible confusion with the trigraph 'air' 610:13,080, particularly when it is followed by a vowel (prepairednes) 195:1707. It would be irresponsible to risk ambiguity when a notation free of misinterpretation is available.

The digraph 'ay' is not susceptible to double interpretation. In the terminal position it is more easily recognized than 'ae' (play, day vs plae, dae), but in other locations it becomes uncomfortable. Its unfamiliarity in medial positions (brayn, layk, saym) may make 'ay' less compatible overall than the less familiar but fairly obvious 'ae' which follows the regularity of American long vowels and has no long-standing pattern of use to be overcome (braen, lack, saem).

The corpus, of course, shows only 'ae'. One can visualize 'ay' or 'ai' in the 'ae' positions and perhaps reach some conclusion as to the merit of either or neither. Copies of a full ay-ai set can be made available to those who wish to give the matter detailed study (page 278).

TERMINAL LONG VOWELS

Dropping the final e from words ending in certain long vowels (wet, alibie, got) shortens 552 words, saves 52,598 letters in a million words, and significantly improves American's compatibility with English.

OE, IE. Reductions are appropriate for oe (no, go, flo, elbo, sb, alto, domino, tho, chebo, tempo, thro, funlo, torso, yelo 350:13,313), and for ie (I, hi, hi-fi, ni, H, compli, counterspi, dri, tn, fli, bi, mi 197:18,162).

EE. The advantage of reducing ee is less certain. One does not feel comfortable in removing the final e from see, free, flee, fee, tree, three, trustee, etc. 398:2530. On the other hand we would not want to see an extra e added to the five short words "he, she, me, we, be" 5:23,933. This accounts for the rule in the box below, which makes an exception of these five short words.

AE. Reducing terminal ae to 'a' is not possible. It would create a conflict with 390:24,730 words ending in schwa-a (camera, extra, stigma, trivia, vista, etc.). Terminal 'a', therefore, always denotes a schwa.

UE. Reducing terminal ue to 'u' would sacrifice the familiar ending of a score of English words (subdue, argue, continue, value, avenue, rescue) for little gain. It would also rule out the most obvious and natural respelling (nue, intervue, curfue, nefue) of 27:3038 words now ending in ew. . Terminal ue, therefore, is not reduced. This means that no words in American end with u.

An area that needs further consideration is the desirability of retaining terminal e where it matches traditional spelling (trustee, agree, belie); particular where the final e, tending to indicate stress on the last syllable, distinguishes between two words with differing pronunciations: beboe (below), bebo (bellow).

Reductions of long vowel prefixes offer a clean gain in legibility. When a hyphen follows a prefix it indicates that the vowel is long (co-ed, re-arm, de-limit, thunmoelectric, re-enter, di-urnal, bi-lateral, re-print 708:1535). An ajacent preceding

vowel is also long (bio-, neo-, jeo- compare, for instance, these two: jco-thurmaljeolojy). -

RULE Final e is dropped from her, she, wee, met, beo and from words ending in ie (justifi) and oe (banjo). The e must be restored before suffixes are added (dri driely; embargo embargoed). A hyphen may replace the final e of a stressed prefix (re-enter, di-urnal, co-author).

The SCHWA

DILUTED A E I 0 U

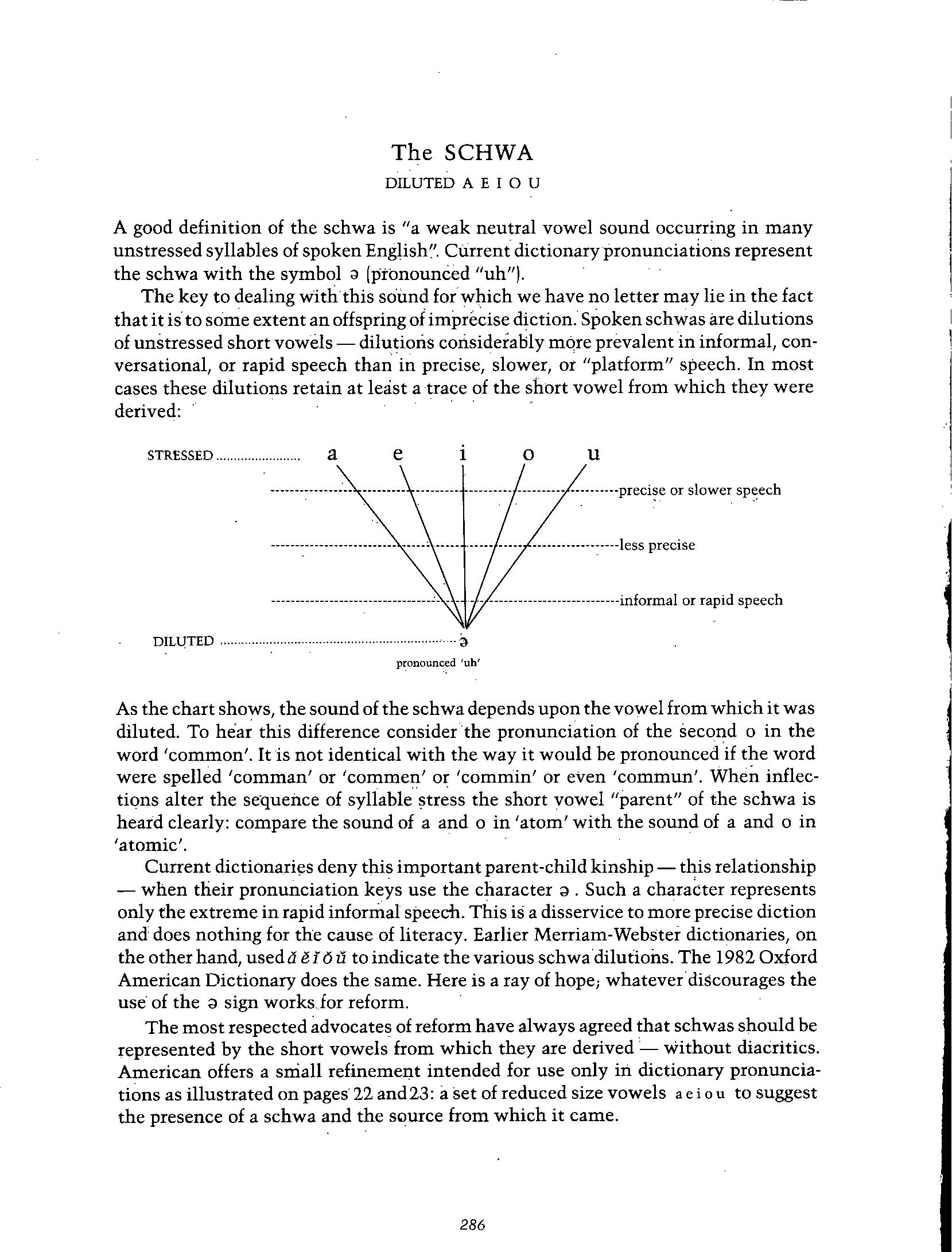

A good definition of the schwa is "a weak neutral vowel sound occurring in many unstressed syllables of spoken English". Current dictionary pronunciations represent the schwa with the symbol a (pronounced "uh").

The key to dealing With this sound foiwhich we have no letter may lie in the fact that it is to some extent an offspring of imprecise diction. Spoken schwas Are dilutions of unstressed short vowels - dilutions considerably more prevalent in informal, conversational, or rapid speech than in precise, slower, or "platform" speech. In most cases these dilutions retain at ledst a trace of the short vowel from which they were derived: -

STRESSED ........................a e 1 0 U

r slower speech

ise

DILUTED ...................................................................

pronounced oh' or rapid speech

As the chart shows, the sound of the schwa depends upon the vowel from which it was diluted. To hear this difference consider the pronunciation of the second o in the word 'common'. It is not identical with the way it would be pronounced if the word were spelled 'comman' or 'commen' or 'commin' or even 'commun'. When inflections alter the sequence of syllable stress the short vowel "parent" of the schwa is heard clearly: compare the sound of a and o in 'atom' with the sound of a and o in 'atomic'.

Current dictionaries deny this important parent-child kinship - this relationship - when their pronunciation keys use the character a. Such a character represents only the extreme in rapid informal speech. This is a disservice to more precise diction and does nothing for the cause of literacy. Earlier Merriam-Webster dictionaries, on the other hand, used a e Too to indicate the various schwa dilutions. The 1982 Oxford American Dictionary does the same. Here is a ray of hope; whatever discourages the use of the a sign worksf or reform. -

The most respected advocates of reform have always agreed that schwas should be represented by the short vowels from which they are derived - Without diacritics. American offers a small refinement intended for use only in dictionary pronunciations as illustrated on pages 22 and 23: a set of reduced size vowels a e i o u to suggest the presence of a schwa and the source from which it came.

The SCHWER

Unstressed ER, AR, OR

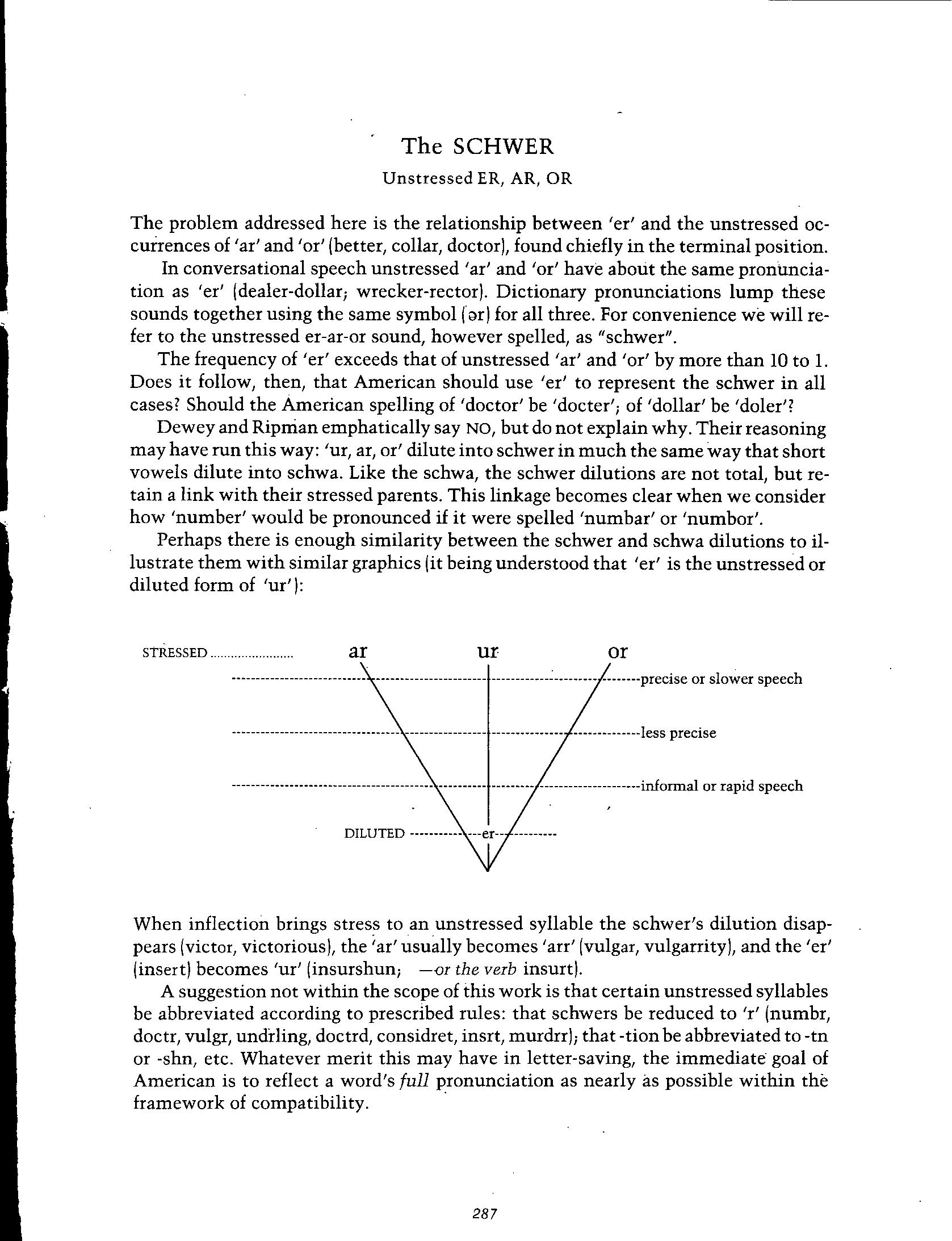

The problem addressed here is the relationship between 'er' and the unstressed occurrences of 'ar' and 'or' (better, collar, doctor), found chiefly in the terminal position.

In conversational speech unstressed 'ar' and 'or' have about the same pronunciation as 'er' (dealer-dollar; wrecker-rector). Dictionary pronunciations lump these sounds together using the same symbol (or) for all three. For convenience we will refer to the unstressed er-ar-or sound, however spelled, as "schwer".

The frequency of 'er' exceeds that of unstressed 'at' and 'or' by more than 10 to 1. Does it follow, then, that American should use 'er' to represent the schwer in all cases? Should the American spelling of 'doctor' be 'docter'; of 'dollar' be 'doler'?

Dewey and Ripman emphatically say NO, but do not explain why. Their reasoning may have run this way: 'ur, ar, or' dilute into schwer in much the same way that short vowels dilute into schwa. Like the schwa, the schwer dilutions are not total, but retain a link with their stressed parents. This linkage becomes clear when we consider how 'number' would be pronounced if it were spelled 'numbar' or 'numbor'.

Perhaps there is enough similarity between the schwer and schwa dilutions to illustrate them with similar graphics (it being understood that 'er' is the unstressed or diluted form of 'ur'):

STRESSED ........................ar ur or

r slower speech

ise

or rapid speech

When inflection brings stress to an unstressed syllable the schwer's dilution disappears (victor, victorious), the 'ar' usually becomes 'art' (vulgar, vulgarrity), and the 'er' (insert) becomes 'ur' (insurshun; —or the verb insurt).

A suggestion not within the scope of this work is that certain unstressed syllables be abbreviated according to prescribed rules: that schwers be reduced to 'r' (numbr, doctr, vulgr, undrling, doctrd, considret, insrt, murdrr); that -tion be abbreviated to -tn or -shn, etc. Whatever merit this may have in letter-saving, the immediate goal of American is to reflect a word's full pronunciation as nearly as possible within the framework of compatibility.

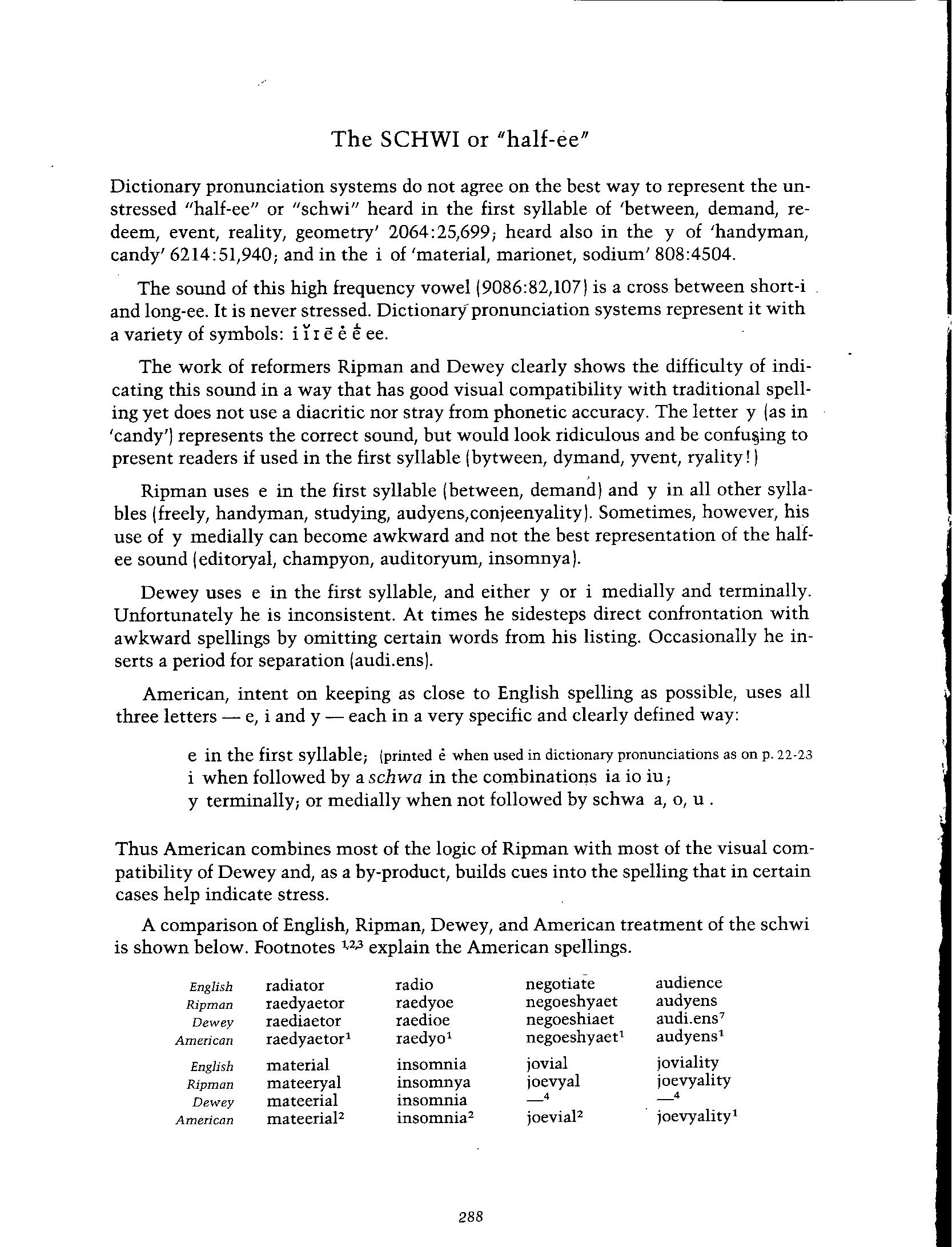

The SCHWI or "half-ée"

Dictionary pronunciation systems do not agree on the best way to represent the unstressed "half-ee" or "schwi" heard in the first syllable of 'between, demand, redeem, event, reality, geometry' 2064:25,699, heard also in the y of 'handyman, candy' 6214:51,940; and in the i of 'material, marionet, sodium' 808:4504.

The sound of this high frequency vowel (9086:82,107) is a cross between short-i and long-ee. It is never stressed. Dictionary pronunciation systems represent it with a variety of symbols: i Tie é & ee.

The work of reformers Ripman and Dewey clearly shows the difficulty of indicating this sound in a way that has good visual compatibility with traditional spelling yet does not use a diacritic nor stray from phonetic accuracy. The letter y (as in 'candy') represents the correct sound, but would look ridiculous and be confusing to present readers if used in the first syllable (bytween, dymand, yvent, ryality!)

Ripman uses e in the first syllable (between, demand) and y in all other syllables (freely, handyman, studying, audyens,conjeenyality). Sometimes, however, his use of y medially can become awkward and not the best representation of the halfee sound (editoryal, champyon, auditoryum, insomnya).

Dewey uses e in the first syllable, and either y or i medially and terminally. Unfortunately he is inconsistent. At times he sidesteps direct confrontation with awkward spellings by omitting certain words from his listing. Occasionally he inserts a period for separation (audi.ens).

American, intent on keeping as close to English spelling as possible, uses all three letters - e, i and y - each in a very specific and clearly defined way:

e in the first syllable; (printed é when used in dictionary pronunciations as on P. 22-23 i when followed by a schwa in the combinations ia io iu, y terminally; or medially when not followed by schwa a, o, u.

Thus American combines most of the logic of Ripman with most of the visual compatibility of Dewey and, as a by-product, builds cues into the spelling that in certain cases help indicate stress.

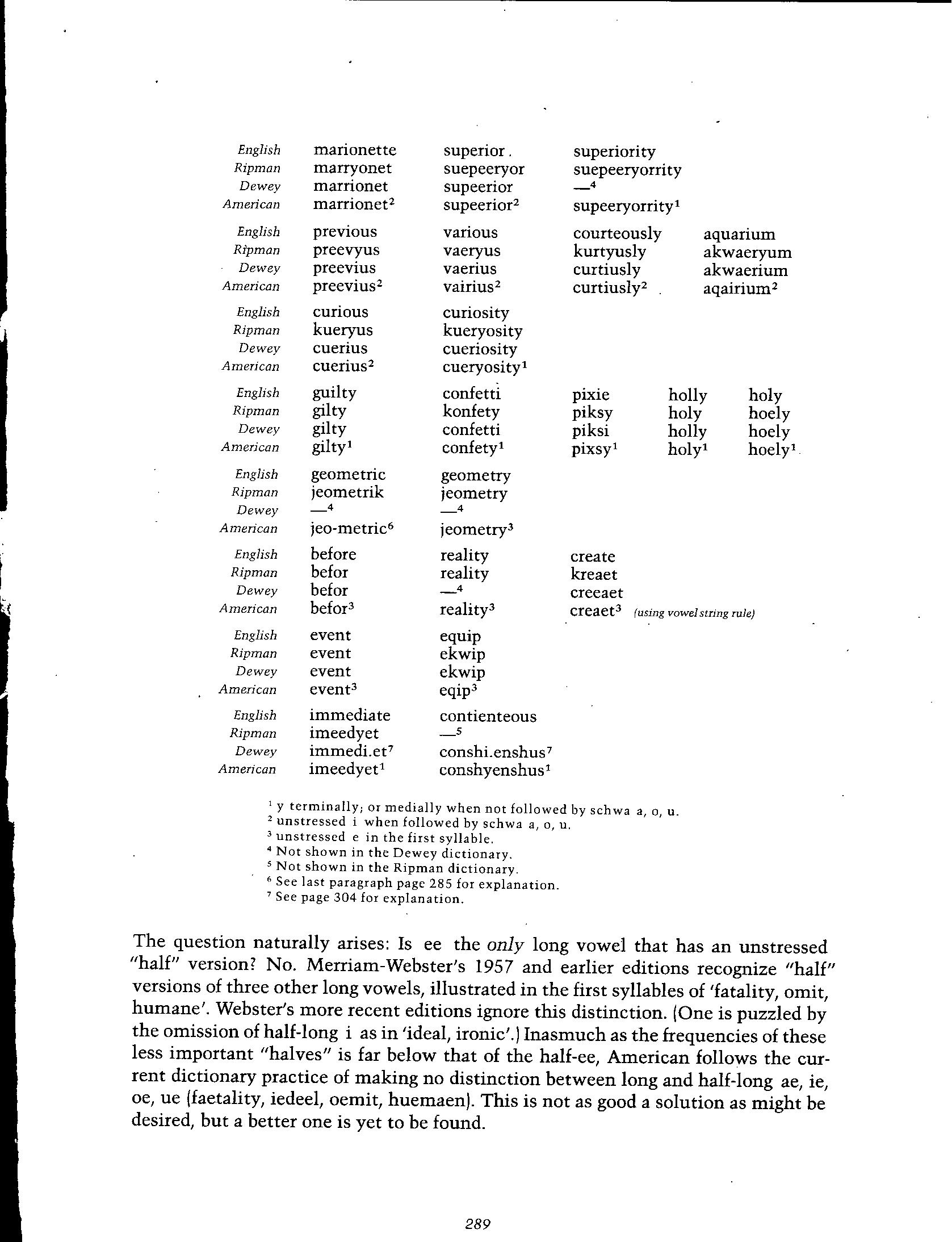

A comparison of English, Ripman, Dewey, and American treatment of the schwi is shown below. Footnotes Z23 explain the American spellings.

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American radiator raedyaetor raediaetor raedyaetor1 material mateeryal mateerial mateerial2 radio raedyoe raedioe raedyo1 insomnia insomnya insomnia insomnia2 negotiate negoeshyaet negoeshiaet negoeshyaetl jovial j oevyal

4 joevial2 audience audyens audi.ens7 audyensl joviality joevyality

4 joevyality1

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American

English Ripman Dewey American marionette marryonet marrionet marrionet2

previous preevyus preevius preevius2 curious kueryus cuerius cuerius2 guilty gilty gilty gilty' geometric jeometrik

4

jeo-metric6 before befor befor bef or3

event event event event' immediate imeedyet immedi.et imeedyet' superior. suepeeryor supeerior supeerior2 various vaeryus vaerius vairius2 curiosity kueryosity cueriosity cueryosity1 confetti konfety confetti confety' geometry jeometry

4

jeometry3 reality reality

4

reality equip ekwip ekwip eqip3 contienteous

S

conshi.enshus conshyenshus' superiority suepeeryorrity

4

supeeryorrity' courteously aquarium kurtyusly akwaeryum curtiusly akwaerium curtiusly2 aqairium2

pixie holly holy piksy holy hoely piksi holly hoely pixsy1 holy' hoely'

create kreaet creeaet

creaet3 (using vowel string rule)

2 y terminally; or medially when not followed by schwa a, unstressed i when followed by schwa a, o, u. 0, u. unstressed e in the first syllable. 'Not shown in the Dewey dictionary.

Not shown in the Ripman dictionary. 6 See last paragraph page 285 for explanation.

See page 304 for explanation.

The question naturally arises: Is ee the only long vowel that has an unstressed "half" version? No. Merriam-Webster's 1957 and earlier editions recognize "half" versions of three other long vowels, illustrated in the first syllables of 'fatality, omit, humane'. Webster's more recent editions ignore this distinction. (One is puzzled by the omission of half-long i as in 'ideal, ironic'.) Inasmuch as the frequencies of these less important "halves" is far below that of the half-ee, American follows the current dictionary practice of making no distinction between long and half-long ae, ie, oe, ue (faetality, iedeel, oemit, huemaen). This is not as good a solution as might be desired, but a better one is yet to be found.