36 minute read

Abolitionist

ABOLITIONIST Clarkson’s Calling

A quiet academic destined for a promising and steady career in the church experiences a Damascene moment when he considers the contents of his winning essay and concludes he has no other choice than to form “a resolution from which he dare not resist”. The history of the abolition of the slave trade is bound in that moment.

Advertisement

Close to the docks in Bristol city centre there is a small pub called the Seven Stars – after the constellation better known as The Plough or the Big Dipper – tucked away behind the well-known live music venue, The Fleece. You could easily miss it, but outside there is a blue plaque dedicated to Thomas Clarkson (1775-80) and his objective of collecting first-hand accounts from seamen involved with the slave trade, often found in this and other local hostelries.

A short while ago I was inspired to go to Juliet Gilkes Romero’s new play for the RSC at Stratford after reading a review in The Guardian. The play’s double entendre title, The Whip, cleverly conjures both the lash used to drive slaves and simultaneously, the member appointed by a political party to enforce party discipline and to secure the attendance of party members at important sessions. The latter in this case being Alexander Boyd, Chief Whip of the Whig Party at the time the Anti-Slavery Act was passed by Parliament in 1833.

The review mentioned the extraordinary fact that the Treasury had announced, by Tweet, just two years ago, that the compensation paid by British taxpayers to slave owners had been finally paid off in 2015. In somewhat flippant prose the tweet announced: “Here’s today’s surprising #FridayFact. Millions of you helped end the slave trade through your taxes. Did you know? In 1833, Britain used £20 million, 40% of its national budget to ‘buy freedom for all slaves in the Empire’. The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Act was so large that it wasn’t paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.” The tweet was roundly attacked and was removed shortly after publication online.

So… a pat on the back for us good tax-paying Brits? Romero’s play, enriched with deep research and peopled with characters from all sides of the slavery story, male and female, unveils another not-so-virtuous narrative. There is unfettered greed on the part of slaveowners, including prominent MPs of the day such as Gladstone, bargaining up payback in return for their support of the bill. There are twisted tales of supposed negro naivety and incompetence used to enforce a further seven years of non-paid apprenticeship on the ‘freed’ slaves which rapidly takes the shine off any idea that the compensation signed off slavery at a stroke, or that ‘owners’ got that it was an immoral trade. That it took us a further 182 years to pay off (equivalent to £15billion in today’s money), thereby including taxes paid by descendants of slaves during that time, must have been the Treasury’s closestheld secret till a minion was lost for something to put out as that ‘FridayFact’. As a Bristolian I am acutely aware that the city’s history has a darker side. Recently, to mark anti-slavery day, an unofficial ‘guerrilla’ art exhibit was laid out at the foot of the statue of Edward Colston, MP, merchant, philanthropist and slave trader, that sits in the city centre, close to the concert hall still bearing his name. 100 ceramic figures were lined up below him to resemble the cargoes of slaves packed into ships en route for the Caribbean and North America.

This subversive artwork, the blue plaque at the Seven Stars and Romero’s play conspired to awaken my interest in the life of Thomas Clarkson and what he learned and witnessed in my home town 233 years ago.

I probably have little need to remind Old Paulines of Clarkson’s career trajectory. But for those, like me, who may have little detailed knowledge; here are some basics.

Clarkson was born on 28th March 1760, the son of Rev John Clarkson who was headmaster of the local free grammar school in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire. Thomas was admitted to St Paul’s in October 1775 at the age of 15. His High Master was Dr Richard Roberts, who had a reputation for “only coming to life when plying the cane”. Clarkson managed to survive or avoid Roberts’

attacks and gained himself a place at St John’s College, Cambridge in 1779, having won both a Gower and a Pauline Exhibition worth some £60 per annum. He gained his BA in 1783 with a First in Mathematics. He was ordained as a Deacon but never proceeded to priest’s orders.

It was while at Cambridge in 1784 that Clarkson won the Latin essay for middle bachelors. No one had yet won two consecutive essay prizes at the university, but Clarkson was determined to do so. Whilst reading for his MA, Clarkson entered the competition for senior bachelors on a question set by the then Vice-Chancellor, Dr Peter Peckard: Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare? (Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?). Peckard was an advocate of civil and religious liberty, believing ‘the heaviest judgement of Almighty God’ would ‘come down on the slave trade’. He had also been enraged by reports, published in 1783, of slaves being thrown overboard from the ship Zong, whose captain had sought insurance pay-outs for their ‘loss’.

Clarkson only had two months to overcome his profound ignorance of the essay subject. His primary sources were the papers of a dead friend who had worked in the slave trade and the eye witness accounts of slavery from officers who had served in the West Indies during the American war, including from his brother John, then a naval lieutenant. He also chanced upon a new edition of Anthony Benezet’s Some Historical Accounts of Guinea, with an enquiry Into the Rise and Progress of the Slave Trade, published by a recentlyformed Quaker committee devoted to exposing the evils of the trade.

During his preparatory work Clarkson wrote: “It was but one gloomy subject from morning to night. In the daytime I was uneasy, in the night I had little rest. I sometimes never closed my eyelids for grief.” It later became his hope that what had started as a trial for academic reputation would transform into a work that “might be useful to injured Africa.” At the conclusion of his essay, written in Latin, he was summoned back to Cambridge to read it, to “generous applause in the Senate House”.

As Clarkson rode back to London he described being in a state of agitation, choosing at times to dismount and walk for a while before climbing back in the saddle. Above Wadesmill in Hertfordshire he remarked: “I sat down

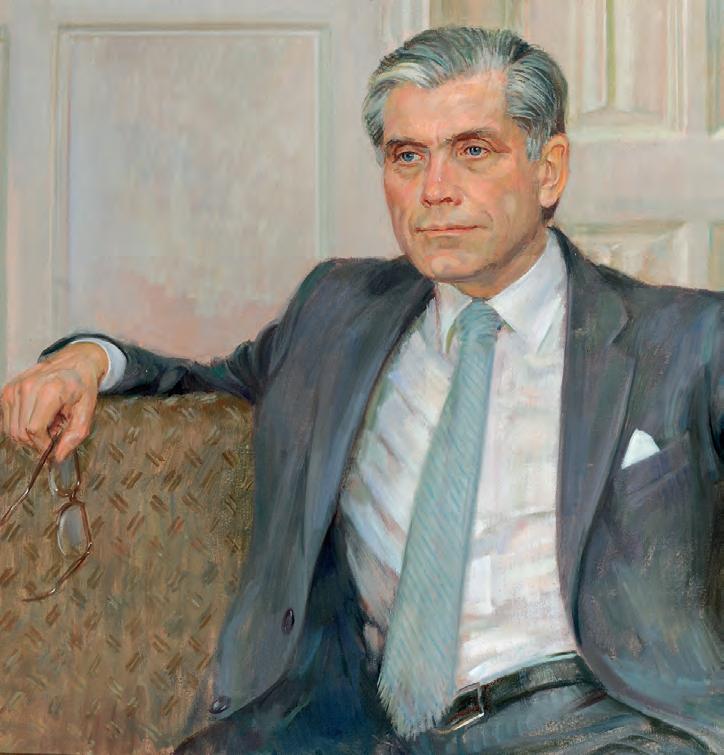

Thomas Clarkson by Carl Fredrik von Breda Oil on canvas, 1788 (National Portrait Gallery 235)

disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. If the contents of the essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to the end.” In 1785 Clarkson expanded and translated his essay into English for the general public, something he was nervous of doing for fear of exposure to criticism. It was published simultaneously in Britain and in America.

Over the next few years Clarkson covered some 35,000 miles on horseback while researching the realities of the

slave trade, beginning in the Port of London, and continuing on to Liverpool and Bristol. He also travelled to revolutionary France to seek support. On reaching the West Country port he noted, “It filled me, almost directly, with a melancholy for which I could not account. I began now to tremble, for the first time, at the arduous task I had undertaken, of attempting to subvert one of the branches of the commerce of the great place which was now before me.”

Clarkson found people willing to talk at first but rapidly ran into walls of silence as news of his mission spread. Later, his life was threatened in Liverpool when he narrowly escaped the attentions of a gang intending to throw him off the pier.

But having befriended Mr Thompson, the landlord of the Seven Stars in Bristol, he started to make progress. Through this association he began to build up a picture of how many crew members perished in the trade, and who had been inveigled against their will to join ships. This would prove to be a compelling part of his anti-slave trade rhetoric. Similarly, his collection of African artefacts would help to convince public opinion of the civilised, cultured nature of the people being forced into servitude and the possibility of other, more lucrative trades that could be followed, such as in wood, honey and leatherwork.

Influential Quaker groups gave Clarkson unrelenting support and direction, leading him to set up the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and ultimately a meeting with William Wilberforce, an independent MP for Yorkshire, a man he could eventually count on to bring an anti-slavery bill before Parliament, and who recognised Clarkson’s book as decisive in steeling his resolve, eventually leading to the Slave Trade Act of 1807.

In his preface to the book The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the Slave Trade, published in 1808, as well as stating that the Bill had not gone far enough, he stated: “I scarcely knew of any subject, the contemplation of which is more pleasing than that of the correction or of the removal of any of the acknowledged evils of life; for how we rejoice to think the sufferings of our fellow-creatures have been thus, in any instance, relieved, we must rejoice equally to think that our own moral condition must have been necessarily improved by the change.”

It would be a further 26 years before slavery would be abolished throughout the British Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, and a further five before full emancipation in 1838. But Clarkson remained a pillar of reform throughout. Referring to his sense of calling at a speech delivered at Exeter Hall in 1840 he said, “I have often indulged in the belief that this feeling might have come from God. To him therefore, and not to such a creature as myself, you are to attribute all the honour and all the glory.”

Postscript St Paul’s School has proudly embraced Clarkson’s name and has sought to emulate some of his selfless qualities since his death in 1846. In 1962, the Clarkson Society was founded with a remit to promote social service activities and assist the Borough Welfare Association by visiting old and lonely people living in Hammersmith. A series of speakers visited the Society including Mr Tony Benn MP in May 1963, who spoke to over 100 boys about the problems then facing the nation, including the ban on black people driving Bristol buses, which eventually led to the passing of the first Race Relations Act of 1965, making racial discrimination unlawful.

On the wall outside the library today you will find a poster promoting the Clarkson Award. The award is made to the pupil “who has consistently demonstrated traits and attitudes the School deems exemplary, including but not limited to exceptional leadership, bravery, support of others and commitment to voluntary service and/or charity work.” The Clarkson legacy lives on.

The School’s rare books archive contains a number of Clarkson first editions. Most notably it holds a first edition copy of The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament (2 Volumes, 1808), which features the iconic diagram of the Brooke’s slave ship. It also has a handwritten letter by him, written in 1813, which includes some of his personal thoughts on Quakerism to a friend. Clarkson’s obituary ‘beetle’ is currently hanging in the Kayton library as do a couple of engravings of him. My thanks to Ginny Dawe-Woodings who kindly provided access to the archive’s collection.

Simon Bishop (1962-65)

Thomas Clarkson Engraving, 1847 from a painting by S Lane

MENTAL HEALTH THEN AND NOW A BOARD ROOM PERSPECTIVE

Tom Hayhoe has been chairman of West London NHS Trust since 2015 and for many years was closely involved as a friend in the care of Robert Silver, whose obituary appears in this edition of Atrium.

Arriving at St Paul’s from a comprehensive school in the late 1960s, about the only Latin I recognised was “Mens sana in corpore sano”. Looking back from my current role chairing an organisation providing mental health services for a large part of the school’s catchment, I recall plenty of provision for “corpore sano” but precious little for “mens sana”.

Physical wellbeing was ostensibly part of the purpose of compulsory rugby in the autumn term and in the wide choice of sport during the rest of the year. A local GP served as school doctor, undertaking periodic physical checks as we passed through adolescence. For those who didn’t head home at the end of the school day, the School House and High House matrons administered aspirin gargles for any ailment irrespective of diagnosis. On the other hand, any provision or concern for our mental wellbeing beyond the tutorial system was well concealed.

The picture today is very different. St Paul’s is deservedly recognised as a pioneer and leader for its investment in mental wellbeing. It has a dedicated senior member of staff, Sam Madden, designated as Deputy Head (Wellbeing and Mental Health). All tutors complete an externally accredited two-day Mental Health First Aid course. Paulines attend lectures from external mental health campaigners. The School is piloting an on-line tool for tracking the emotional wellbeing of younger boys. 8th Formers run a society called ‘MindMatters’ with the goal of tackling mental health related stigma and promoting positive wellbeing. The importance of this work is demonstrated by the evidence for increasing pressures on the mental wellbeing of teenagers: the rate of referral nationally into NHS child and adolescent mental health services doubled between 2012/13 and 2018/9.

The disparity nationally between the status of mental and physical health in the 1960s was enormous. However, change was already on the way. New psychiatric medicines were coming on stream and the emphasis was shifting from treating people in hospital to supporting them in the community. The decade opened with a speech delivered by Enoch Powell as Minister of Health to the National Association for Mental Health that has passed into NHS legend: “This is a colossal undertaking…. in the sheer inertia of mind and matter which is required to be overcome. There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooked over by the gigantic water tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside – the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day…. We have to strive to alter our whole mentality about hospitals and about mental hospitals especially... We have to get the idea into our heads that a hospital is a shell, a framework, however complex, to contain certain processes, and when the processes change or are superseded, then the shell must most probably be scrapped.”

Fifty to sixty years on, the approach we take to mental health is transformed but there is still much to be done. The water towers have gone and most of the old asylum buildings have been demolished or repurposed as desirable residential developments. A few vestiges of the old mental health estate remain including, scandalously, some dormitory style wards. The NHS Trust that I chair is desperate for capital to move from the remaining pre-Victorian wards it occupies at the St Bernard’s Hospital (originally built as the Hanwell County Asylum). It was only last December that we finally moved the patients at Broadmoor High Secure Hospital from buildings erected in 1863 to an environment fit to support the recovery of men who are extremely unwell and a high risk to themselves as well as the public, preparing them for an eventual return, via less secure hospitals or prison, to life in the community.

The transformation in the approach to mental health involves more than the relocation of people with acute mental illness from long-term hospitals. As a lay person working in this area, my impression is that the change results from continual improvement in the clinical understanding of mental illness and the tools for helping people experiencing difficulties in their mental health.

Our mental health reflects a huge range of potential influences: genetic inheritance, organic illness throughout our life, psychological influences in our families, upbringing, working and domestic lives, traumatic events, what we put into our bodies – not just drugs (prescribed or otherwise) and alcohol – but the food we eat and the accompanying organisms (both good and bad for us) that affect our individual gut flora. This is no different to other aspects of our health. While there may be specific immediate causes for our “-itis”, “-algia”, “-opathy”, or “-noma”, the upstream causes, our susceptibility, and our ability to cope with physical health conditions are just as diverse as those determining our mental health. We are hugely complex organisms exposed to an almost infinite variety of external factors and experiences.

Correspondingly, professions in mental health that have traditionally been at loggerheads about treatment methods are increasingly accepting of the wide range of interventions to help recovery or at least manage symptoms. Antipsychotic drugs over the years have become more effective for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, some bipolar disorder and severe depression by reducing or controlling symptoms, and have fewer side effects. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), extensively used for people with much less acute conditions, can also assist by providing these patients with strategies to help cope with unpleasant or difficult experiences arising from the underlying psychotic condition. Similarly, while some people with anxiety or depression come through their condition with psychological therapies alone, others benefit from medication, most commonly from one of the classes of serotonin reuptake inhibitors that increase the level of an important naturally occurring neurotransmitter in the brain.

The change in the pattern of mental health care delivery for those in most acute need has been dramatic. The number of mental health inpatient beds in England fell from 130,000 in the 1940s to 80,000 by the mid-1980s and currently stands at 19,000, made possible by more effective therapeutic interventions and a shift in resources. Looking at international comparisons, the reduction could go further: the average length of stay in an inpatient mental health unit in England is 32 days, compared to 11 days in Australia and 9 days in Sweden. However, to make progress we need to invest more in support for patients following discharge from hospital, not least around social care needs and housing.

The biggest change in the delivery of mental health care in the UK has been in the improved support for people with less acute problems, such as mild depression and anxiety, through the delivery of psychological therapies under the IAPT (Improved Access to Psychological Therapies) programme launched by the Labour government in 2008 and taken up with enthusiasm first by the Coalition and since by the Conservatives. 1.1 million courses of treatment were delivered during last year and the ambition in the NHS Long Term Plan is for this to increase to 1.9 million. The benefits of this investment are twofold: psychological therapies help most of the people referred to the service address their symptoms and get back on track; and, for those with deeper underlying problems, symptoms are spotted earlier and the risk of potentially longer term problems mitigated.

The good news for anyone with an interest in mental health is the increased interest in the area. Prince William and Prince Harry have emerged as great champions. There is progress in the commercial world, with exemplary leaders being open about their own mental health challenges, employers recognising the need to take more care of their staff and engage in programmes such as Mental Health First Aid, and the success of initiatives like the City Mental Health Alliance. Our politicians are increasingly interested in mental health, evidenced by the increase of mentions of mental health in the party manifestos: the Conservative Party’s general election manifesto carried five mentions in 2015, rising to 35 in 2017, and Labour’s four mentions in 2015 and 13 in 2017.

As chair of an NHS Trust providing mental health services, I take heart from the commitment of the Department of Health and Social Care to increasing the funding for mental health. And as OPs we can be proud of our association with a school that now treats the mental wellbeing of its pupils as an equal priority with its tradition of academic excellence.

Tom Hayhoe (1969-73)

MENTAL HEALTH TODAY A PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

Men’s mental health is gaining more and more exposure, which can only be a good thing. If your eyes do not work so well, you wear spectacles.

If you have a broken arm, you have a plaster cast until it is better. The same applies to mental health. There is no shame in admitting part of your body does not work properly even if it is your brain.

However, professional and researched help is available (NHS and/or privately) for those who suffer from this debilitating and scary illness. Mental illness/ psychological trauma / being a bit nuts, however you are comfortable in labelling any issues you might have, the message is clear: there is nothing to be ashamed of. If you need it, get help from your GP or, in emergency the crisis line for your local NHS Trust.

Previous generations used euphemistic phrases like “midlife crisis”, “nervous breakdown”, “the only difference between madness and eccentricity is wealth”, “the men in white coats“ etc. etc. These are not helpful in addressing what is a very serious issue, and one that affects a quarter of the population in any given year. Depression is not the same as sadness. Anxiety is not the same as trepidation. Bipolar is not the same as having an off day. Psychosis is not the same as disappointment.

Part of the problem is our understanding of these and related words. Personally, I use the term “a little bit nuts”; it deflects sympathy but maintains gravitas. It is no longer okay to sweep mental health issues under the carpet, as our forefathers had to. Another part of the problem is that men are under-diagnosed, we are all stubborn and many of us are introspective; that does not mean we are not susceptible, no matter how much it piques our masculinity.

The audience for this magazine is largely professional, intelligent, and high achieving men. We all have St Paul’s School in common although time and distance may separate us. As members of this (or any) community it behoves us to help one another in the spirit of common decency and good manners.

Mental illness is like a cold sore; while it may not be always flared up, it is always there in the background with the potential to appear at any trigger. Although I am probably not qualified to have an opinion on this, I think that the sociocultural awakening for this generation will be that it is okay to have mental health issues. Our greatgrandparents’ views on race and grandparents’ attitudes towards homosexuality are unsavoury to the modern palate. Where Martin Luther King and the Stonewall movement spearheaded breakthroughs for those generations, I am hopeful that one legacy we can hand down is tolerance of psychological divergence. While one could never condone intervention for issues of race and sexuality, with mental health, treatment is proven to improve quality of life.

If you have advised a loved one to see a doctor when they felt unwell, take your own advice. Yes, we are all busy, yes none of us want to admit there might be something wrong, and yes we’d see a doctor if one of our fingers fell off.

I am not a mental health professional and can only speak from personal experience. After many years of low mood and disturbing episodes, after the death of my brother from cancer aged just 41, my undiagnosed mental illness spiralled terrifyingly out of control. I was clinging to the wreckage of my own sanity and it was scary. I had become a danger to myself and others, but one visit to my GP set me on the right track. I was not sectioned. She realised that the black dog had me firmly in its jaws and that hallucinations and paranoia were clouding my better judgement. The GP expedited me to the local mental health team who took me on with kid gloves. This was two years ago. Now, with the help of a kind and patient shrink (she prefers to be called a counsellor), and prescribed medication, I am on the road to recovery. would not play a part in my recovery but, by and by, my psychologist and I concluded that it would be the best course of action, alongside therapy. Science has improved since the days of the so-called happy pills.

I was initially prescribed 50mg of sertraline, which was incrementally raised until my present dose (still under supervision by the mental health nurse). Side effects have included double incontinence and fluctuating libido, but the positives far outweigh the negatives.

Everybody is different but in my case the drugs also triggered my sense of taste. Before, I ate out of necessity deriving no pleasure from food. I thought I could taste food in the same way as everyone else, but now I realise that I was wrong. The first food I ever tasted, at the age of 38 was a microwaved cheese pizza; absolutely nothing special, but the flavour explosion I experienced was an epiphany. Mood has been noticeably less low too, yes, there are bad days and good days, but the lows no longer approach the terrifying depths pre-medication. At present I am still not able to work and some days are difficult but, had it not been for the NHS and my GP, my mother would be mourning both her sons.

I do not mean to sound sanctimonious or preachy but if this has resonated in any way with the reader, I strongly encourage you to book an appointment with your GP, be open about any concerns you have. In any other area of life, it is sensible to take professional advice when your own capability falls short, mental health should not be the exception.

Robin Hirsch (1956-61) owner of the Cornelia Street Café in New York for more than 41 years shares a story from a memoir in progress, called THE WHOLE WORLD PASSES THROUGH: Stories from the Cornelia Street Café and includes recollections of two very eminent Paulines who have died recently, Oliver Sacks (1946-51) and Jonathan Miller (1947-53).

Inventory

It’s Thursday, the last day of the week for ordering. I’ve run around downstairs checking paper goods, cleaning supplies, beer, wine, liquor. I come upstairs. It’s lunchtime. It’s May. The sun is shining. The doors are open. It’s busy.

A man is sitting at a table in the side room. I am vaguely aware that he is watching me through the archway. I look up and he beckons me over. “Are you an actor?” he asks.

“Occasionally,” I reply. “Did you do something at the Murphy Center about ten years ago?” “I did a couple of things there.” “Did you do something with Oliver Sacks?” “The neurologist? Yes, I did. Were you there?” “I was. I remember it very well. You did a piece about a Touretter.”

I did, indeed; a couple of plays inspired by Sacks’ case histories. One was A Kind of Alaska by Harold Pinter, which seemed to have emerged almost fullblown some nine years after Pinter had read Awakenings. The other was a monologue by Peter Barnes called Drummer, which had been inspired by a case history of “Witty Ticcy Ray,” who suffered from Tourette’s Syndrome, an affliction of the brain which causes sudden quite violent and scatological eruptions even in the middle of genteel conversation.

We managed to get hold of Sacks. He agreed to come on the night and to talk or at least respond to questions afterwards. Could he bring a friend? Of course.

I directed the Pinter, which is a deliberative, almost elegiac meditation on a woman slowly emerging after twenty-nine years in a coma. Drummer is a very different kettle of fish. It’s short, it’s abrupt, it’s funny, it’s violent. It’s also a piece that is quite close to me.

As a child growing up in London after the war I had developed fits which never totally left me and which were occasioned by unlikely things that happened at home – my parents smoking, for example. I would begin to tremble and shake and eventually I’d rush to my room to try and block out all kinds of intrusions – my father’s violence, my parents’ unhappiness, early pre-conscious memories of the Blitz during which I was born, the shadow of a history from which my parents had escaped but about which they were silent, who knows what else. These fits were a terrible and mysterious companion of my adolescence, which years of Freudian therapy did nothing to resolve. They made me feel intensely crazy, alien, and alone, and therapy served only to magnify those feelings. Finally in Drummer I’d found a kindred spirit whose tics and twitches I could inhabit and exfoliate.

On the night, out front in the audience amid the generalized hubbub I hear a sudden shout, and then another. The hubbub subsides and what we all then listen to, audience and actor alike, is a series of inchoate staccato outbursts of the kind that I am preparing to deliver. Slowly it dawns on me that Sacks must have arrived and that the friend he had said he was bringing with him must be a Touretter – the genuine article as opposed to the fake that I was preparing to become.

I don’t think I have ever been as nervous before a performance as I now became. The lights went out, and, in the darkness and the dreadful interrupted silence, I stumbled out towards the drum set. Now there were two Touretters in the house, the real one and a bogus one people had paid money to see. The lights came up. I picked up my drumsticks and in a strangulated voice began to speak.

I twitched, I shouted, I banged my drums. And every so often out in the audience someone unseen twitched and shouted with me. Together we built to a climax and then finally it was over.

After a break Sacks, a large, rumpled, and surprisingly shy man sat on the stage and responded with some hesitation and considerable thoughtfulness to questions from the audience. He introduced his friend the Touretter, and, inevitably, in that small theatre, with so much revelation and such cloistered intimacy, a three-way conversation ensued.

There was a party afterwards. Sacks, I learned, had gone to the same school, St Paul’s as I in London, though some ten years earlier. He and Jonathan Miller had been friends there. Both had become doctors, though Miller had achieved enormous and very early fame as a comedian. Oddly, though Sacks had none of the manic performance energy that Miller brought so brilliantly to bear in Beyond the Fringe, there was, it seemed to me, a certain attunement to a kind of human, or perhaps, more accurately, divine, comedy in the shy neurologist, an understanding.

As with so many things in the performing life it was a one-night affair. Magical but written on the wind. I never saw Sacks again, though I kept up with some of his writing and the memory of that evening never left me, and lingered perhaps even for others.

“So, yes,” I said to my interrogator, “I did indeed play a Touretter. You were there?”

“I was indeed,” he said. “I am the Touretter,” and he barked and leaned over and punched me in the chest.

“You are the Touretter?” “Yes. Oliver brought me with him.”

I said, “I’ve written a book, a memoir, since we last met. It has nothing to do with Tourette’s, or acting, or the café. It’s about growing up in the shadow of the Holocaust. That’s the disease I suffer from. If there’s a copy downstairs I’d like to give it to you.”

I found one. He told me his name and on the flyleaf I wrote:

“For Lowell Handler, who does a pretty good imitation of me. With admiration, Robin Hirsch.”

I handed it to Lowell. He leaned over and punched me in the chest. I punched him back.

Then I returned to my inventory.

Shaping Our Future – OPs Step Up

From its foundation in 1509 St Paul’s has been educational philanthropy in action. The vision of founder, John Colet, was ‘to educate boys to serve society regardless of their race, creed or social background’. The ‘Shaping Our Future’ campaign, launched in May 2019, is seeking to renew this founding vision.

The campaign’s target is £20m. It splits three ways. The target for bursaries is £9.9m, £0.5m is earmarked for partnerships (Paulines volunteering in state schools and School facilities being opened up to state school pupils), and £9.6m for the new boathouse and sports pavilion. The bursary and partnerships target is an ongoing one.

Across St Paul’s Juniors and St Paul’s there are currently 108 bursaries awarded which annually “cost” £2.1m. The equivalent figures in 2016 were 49 and £0.8m. The £2.1m annual bursary cost represents about 6% of fee income in an undisrupted year. When the bursary element of the ‘Shaping Our Future’ campaign is fully funded, the School will be in a position to fund 153 (a full shoal of miraculous fish). To this end an annual target of £3.3m has been set. This will fund these places with any remaining money going in to the bursary endowment to allow the School to move further towards its ‘needs blind’ ambition. £3.3m would represent around 10% of fee income.

Nine months on from launch, income and pledges received to date stand at £6.1m, which represents nearly a third of the target. The majority of this income is towards the bursary and partnership total of £10.4m. This balance matches the focus of communications since the campaign was launched.

OPs have donated 35% of the running total and make up 26% of donors to ‘Shaping Our Future’. 11 OPs are “major donors”. There are 483 members of the 1509 Society (a regular gift of any amount or a single gift of over £500) of whom 130 are OPs. 21 OPs have indicated that they intend to recognise the School in their Will.

If you feel able to join the supporters, here are the links and details of who to contact.

Please do visit the website at donate.stpaulsschool.org.uk for more information, or contact Ellie Sleeman, Director of Development, at: ems@stpaulsschool.org.uk When the bursary element of the ‘Shaping Our Future’ campaign is fully funded, the School will be in a position to fund 153 (a full shoal of miraculous fish).

Feast Service 2020

On 3 February, around a 100 Old Paulines, along with their guests, leaving Upper Eighth students and their parents, gathered in St Paul’s Cathedral for a celebration of Evensong to mark the Feast of the Conversion of St Paul. The choir included members of the St Paul’s School and St Paul’s Juniors chamber choirs. Rev Mark Oakley, Canon Chancellor of St Paul’s Cathedral, and Brian Jones, President of the Old Pauline Club, gave the readings. As Brian Jones noted in his speech at the Mercers’ Hall, it is something of a coup that we are able to celebrate the Feast in this way at the Cathedral, with the School’s own choir singing in a public service. Brian thanked Rev Matt Knox, Chaplain of St Paul’s and St Paul’s Girls’ Schools, for enabling the OPC to maintain such a positive dialogue with the Cathedral.

Following Evensong all made their way to the Mercers’ Hall. Guests were welcomed with an opening speech by Adam Fenwick, House Warden of the Mercers’ Company and Governor of the school. Adam spoke of the history of the Feast and also paid tribute to the outstanding leadership of Professor Mark Bailey, this being his last Feast Service as High Master. Brian Jones followed, speaking of the numerous social and professional networking opportunities open to the leaving Upper 8th students through the OP Club.

As is customary, Brian presented the school with books donated by the Club (Medhurst, W.H. 1838. China: its state and prospects, with especial reference to the spread of the Gospel: containing allusions to the antiquity, extent, population, civilization,

literature and religion of the Chinese; Levick, G.M. 1914. Antarctic penguin: a study of their social habits; and Allan, I. 1942. ABC of Southern locomotives: A complete list of all Southern Railway Engines in service). Hilary Cummings, Librarian at St Paul’s, gratefully accepted the books on behalf of the School. The speeches concluded with the High Master, who gave a glowing review of the support lent by the Mercers’ Company and the Old Pauline Club throughout his time at the School, as well as again thanking the OPs for the book donations.

The buffet supper that followed the speeches enabled Old Paulines from close to a 70- year range of year groups, current students and parents to enjoy the hospitality of the Mercers’ Company.

Reunions

2004 1st XV Squad

1958/59 1st XV

Durham Drinks

Thursday 7 November Held at The Boat Club, Durham Attended by 15 Old Paulines studying at Durham University

2019 Leavers

Thursday 19 December Held at the Rutland Arms, Hammersmith Attended by 60 Old Paulines who left the school in 2019

Singapore Dinner

Winter New York Drinks

Wednesday 5 February Held on Upper East Side in memory of Jamie Morris Attended by 16 Old Paulines

1979 1st XV

New York Lunch

Wednesday 15 January Held at The University Club Attended by 10 Old Paulines and guests

Shop online for OPC Merchandise

Choose, order and pay for your items online. Try it now! Go to:

opclub.stpaulsschool.org.uk/merchandise

Summer or regular OP blazers are available to order

Old Pauline Club Committee List 2019/20

President B M Jones

Past Presidents

B D Moss, C D L Hogbin, C J W Madge, F W Neate, Sir Alexander Graham GBE DCL, R C Cunis, Professor the Rt Hon Lord McColl of Dulwich, The Rt Hon the Lord Baker of Dorking CH, N J Carr, J M Dennis, J H M East, Sir Nigel Thompson KCMG CBE, R J Smith

Vice Presidents

P R A Baker, Professor M D Bailey, R S Baldock, J S Beastall CB, S C H Bishop, J R Blair CBE, Sir David Brewer CMG, CVO, N St J Brooks, R D Burton, W M A Carroll, Professor P A Cartledge, M A Colato, R K Compton, T J D Cunis, S J Dennis MBE, Sir Lloyd Dorfman CBE, C R Dring, C G Duckworth, A R Duncan, J A H Ellis, R A Engel, D H P Etherton, The Rt Hon Sir Terence Etherton, Sir Brian Fall GCVO KCMG, T J R Goode, D J Gordon-Smith, Lt Gen Sir Peter Graham KCB CBE, Professor F D M Haldane, S A Hyman, S R Harding, R J G Holman, J A Howard, S D Kerrigan, P J King, T G Knight, B Lowe, J W S Lyons, I C MacDougall, Professor C P Mayer, R R G McIntosh, A R M McLean CLH, I C McNicol, A K Nigam, The Rt Hon George Osborne , T B Peters, D M Porteus, The Rt Hon the Lord Razzall CBE, The Rt Hon the Lord Renwick of Clifton KCMG, B M Roberts, J E Rolfe, M K Seigel, J C F Simpson CBE, D R Snow MBE, S S Strauss, A G Summers, R Summers, J L Thorn, R Ticciati OBE, Sir Mark Walport FRS, Professor the Lord Winston of Hammersmith

Honorary Secretary

S B B Turner

Honorary Treasurer N St J Brooks FCA

Main Committee

Composed of all the above and P R A Baker (OP Lodge), A J B Riley (Rugby Football Club), T J D Cunis (Archivist & AROPS Representative), C S Harries (Association Football Club), J P King (Colet Boat Club), P J King (Fives Club & Membership Secretary), N H Norgren (Elected), T B Peters (Cricket Club), J Withers Green (Editor Atrium & Social Engagement Officer), J D Morgan (Golfing Society), D C Tristao (Tennis Club)

Executive Committee

B M Jones (President & Chairman of the Committee), R J Smith (Immediate Past President), S B B Turner (Hon Secretary), N St J Brooks (Hon Treasurer) N J Carr (TDSSC Ltd Representative), J H M East (Elected), J A Howard (Liaison Committee Representative), P J King (Elected), J D Morgan (Elected) J Withers Green (Editor, Atrium & Social Engagement Officer)

Liaison Committee

J A Howard (Chairman), I M Benjamin, N J Carr, R J G Holman, T B Peters

Ground Committee

J M Dennis (Chairman), R K Compton, G Godfrey (Groundsman), M P Kiernan, J Sherjan

Accountants

Kreston Reeves LLP