8 minute read

The Women of Sassoon

from March/April 2023

by HadassahMag

Art and Judaica collections highlight overlooked women

By Robert Goldblum

Advertisement

The sassoon men cut quite a figure. Their vast wealth, first as opium traders and merchants and later as art patrons and collectors, stretched from Baghdad to Bombay, today called Mumbai, to the royal corridors of Great Britain.

There was patriarch David Sassoon, often pictured in flowing robes with a long silver beard and intricate headdress, every inch a mid-19th-century Iraqi Jew of means. His business empire moved effortlessly between East and West.

There was his son Sassoon David Sassoon, who established the family’s beachhead in London. Another of his eight sons, Reuben Sassoon, pictured in formal white tie and tailcoat in a Vanity Fair caricature, became ensnared in 1890 in what was known as The Royal Baccarat Scandal, a gambling dispute eventually brought to trial that involved none other than the playboy Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.

As for the Sassoon women, well, in most accounts of a sweeping family saga that spans from 1830 to the end of World War II, they are largely absent.

A new show about the family at The Jewish Museum in New York City, “The Sassoons,” which runs through August 13, aims in part to fill in those absences, shedding light on overlooked Sassoon women. Among them are businesswoman Flora Sassoon, David’s great-granddaughter, who at age 14 married one of David’s sons; and art collector and patron of poets Mozelle (Gubbay) Sassoon, another of David’s great-granddaughters.

“There is a plaque in the Magen David Synagogue in Mumbai”— built by David in 1864—“with an inscription that offers blessings to all eight of his sons,” Claudia Nahson, the show’s co-curator, said. “Where are the women? The women who gave birth to them and raised them? They are just completely absent.

“And these were really forward-thinking women and pioneers in their own way,” she added. Without them, the family’s story “may have been very different.”

Several generations of Sassoon women are given new life in the exhibit, which charts the female family members’ accomplishments, aesthetic tastes and the friendships they struck up with the personalities of their generations. These include, for example, American expatriate artist John Singer Sargent, who captured the Sassoon family in striking Edwardian-era portraits.

The show opens on the heels of Natalie Livingstone’s recently published history The Women of Rothschild, itself a reassessment of the powerful role played by the women in that dynastic Jewish banking family. (In fact, the “houses” of Sassoon and Rothschild merged in 1887 with the marriage of Aline de

Rothschild to Edward Sassoon.)

The Sassoon women are revived as commissioners of exquisite Jewish ritual objects, discerning collectors of sublime 19th-century landscape paintings and expert restorers of grand English manor houses. And they, like their male relatives, cut quite a figure.

In the exhibit, Flora is seen in a photograph from 1900 in Victorian finery. She took the reins of the Mumbai branch of the family business after the death of her husband, Solomon Sassoon—the only Sassoon woman to oversee any part of the company.

It was also Flora who commissioned the wood, silver gilt and enamel round Torah cases, or tikim, that were crafted in China, used in Mumbai and ultimately taken to England. The cases have a prominent place in the show and speak to the continent-spanning reach of the Sassoons.

Another prominent woman in the family was Rachel (Sassoon) Beer, Sassoon David’s daughter. A crusading editor of two British newspapers, she reported extensively on the Dreyfus Affair. She also extended the family’s collecting beyond Judaica and into the realm of fine art. Rachel is seen in the show in Henry Jones Thaddeus’s 1887 portrait, captured in a soft, gauzy light, wearing a delicate silk dress.

And there are cousins representing a generation of Sassoons who came of age in the late 19th and early 20th century. Hannah Gubbay, a Sassoon on both sides, was a sharp-eyed collector of 18th-century porcelain and furniture. According to the exhibition’s catalog, she often roamed country house sales with Queen Mary in tow. Hannah’s cosmopolitan cousin Mozelle was born in 1872 in Mumbai and moved from India to France to England. (Mozelle as well as Flora are frequently used names among the Sassoons.) Her country house in Berkshire had been the home of the celebrated 18th-century English poet Alexander Pope.

As visitors step into the first gallery, they see the portrait of patriarch David Sassoon, painted in tea-colored Baghdadi robes trimmed in scarlet with Mumbai’s Back Bay appearing behind him.

In a nearby gallery hangs a portrait of David’s great-granddaughter Sybil Sassoon. More commonly known as Sybil Cholmondeley, the Marchioness of Cholmondeley, Sargent captured her in a moody charcoal drawing in 1910, pain etched in her young face as she mourned the death of her mother, Aline de Rothschild.

The two portraits, David and

Sybil’s, represent an arc of four generations, and they open a window onto a sprawling family journey that hits on many of the central issues that continue to animate the world: global trade, immigration, acculturation, assimilation and antisemitism. David sat for his portrait in India because the family was driven out of Baghdad

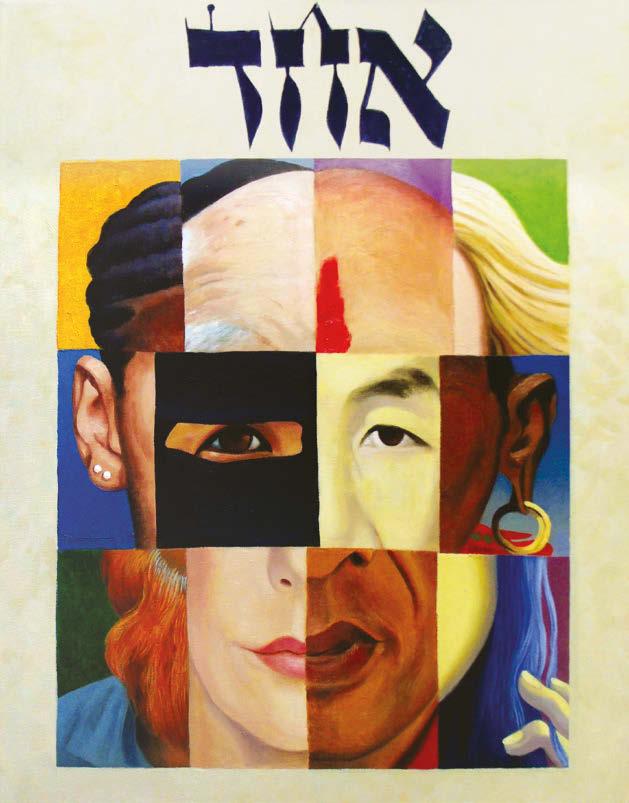

‘ONE NATION,’ AN EXHIBIT ABOUT AMERICAN IDENTITY

In ‘Echad (One),’ artist Alan Falk imagines Americans united by a desire for peace and justice (left); artist Miriam Stern’s ‘Pekelakh’ (bundles) is a reference to the Exodus and the baggage of oppression that Jews and others carried in their wanderings. Both paintings are on display through July, part of the “One Nation” exhibit at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Heller Museum in New York City.

in 1830 by a campaign of persecution.

“Seeing a story through the lens of a family makes it more personal, more accessible,” Nahson said. “It’s a timely show because of all the subjects it dwells upon, and it’s a timeless story, a story of survival, acculturation, preserving your identity yet adapting.”

Indeed, the show hinges on the idea that collecting casts a bright light on identity, in all its complex hues. Each graceful Torah finial, lyri- cal Yuan dynasty handscroll and vibrantly colored illuminated Hebrew manuscript is freighted with emotion, each a kind of way station on the century-long journey of a family lugging its Jewish identity across a fast-changing world.

The things the Sassoon men and women collected, it turns out, were both burden and blessing, pulling

From Stage To Synagogue

Afew words you might not expect to hear at synagogue: The rabbi’s wife is away on national tour.

That is until you are told that the woman on tour is Michelle Azar, an award-winning singer and actress. Azar is currently headlining an acclaimed national run of All Things Equal: The Life and Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg . Back home in Los Angeles, her husband, Jonathan Aaron, is the senior rabbi at Temple Emanuel, a Reform synagogue in Beverly Hills.

All Things Equal is the latest from composer, author and Tony Award-winning playwright Rupert Holmes, whose works include a musical based on The Mystery of Edwin Drood and the play Say Goodnight, Gracie —though he may be best known for the hit 1979 single “Escape (The Piña Colada Song).”

The one-woman show completed runs in Florida and on Long Island, N.Y., last year. All Things Equal began a national tour in February that will end in November in Harrisonburg, Va. (For dates, locations and ticket information, see michelleazar.com .)

The play’s conceit is that the late Supreme Court justice is telling her story to a visitor in her chambers, a young friend of her granddaughter. RBG ages in the show, which travels back and forth in time from her mid-30s to her 80s. While much of the legendary jurist’s career is explored, at the play’s center lies the staggering prejudice she endured as a student, one of only nine women in her first-year class at Harvard Law School in 1956, and as a young female lawyer unable to get a clerkship or find a job with a law firm, even though she graduated from Columbia Law School at the top of her class.

“It is the greatest, most heartbreaking gift to be playing such a person,” said Azar. “The audiences’ audible responses keep me constantly in the moment as I want to be mindful about people’s various views but steadfast to the work RBG was committed to. When there is anything that we see as uncaring, unfair or unequal, any impediments to the equal rights for all people to find their voice and realize their potential, we must ‘dissent.’ Without rage or condemnation, but with simple and clear words.”

“Within seconds of the show starting, the audience believes she is Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” Holmes said about Azar’s portrayal of the late justice. “Her performance earns her a standing ovation every night.” them back toward the long gone world of Jewish Baghdad and hurtling them forward into British high society. It was a bittersweet ride— something gained, something lost.

Each city where the family lived “is a passage into something,” Nahson said. “They start as Baghdadi Jews, then they move to India yet still very much with a Baghdadi identity. Then they go to England, and they shut off some of that. As the generations advance, the spiritual and geographical distances are larger, so they integrate what they brought with them.

That applause might be because Azar intuitively understands how to embody complex women. Her father was born in Iraq, and he immigrated with his family to Israel when he was a young child. After completing his Israel Defense Forces service, he came to the United States, married an Ashkenazi woman and settled in Brooklyn. Azar has called herself the “product of intermarriage” of two Jews. She explored the intricacies of that rich family heritage as well as the prejudices experienced by Jews from Arab countries in her 2017 one-woman play, From Baghdad to Brooklyn.

“I always knew we were Jewish,” she said of her traditional Sephardi upbringing. “But Jewish differently.”

“But sadly,” Nahson concluded about the wealth and objects collected by the Sassoons, “some of it is gone,” sold at auction and victim to the extended family’s shifting fortunes in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

But not all of it. In a diary entry from 1910, Mozelle Sassoon, Flora’s daughter, writes tenderly of the Torah scroll used during Rosh Hashanah services at the Great Synagogue of Baghdad. It was one of two scrolls encased in ornate tikim, commissioned by her mother, that the family held onto.

After earning an undergraduate degree in drama from New York University, Azar landed the role of Janis Joplin in the Off-Broadway musical Beehive . Exhausted from the all-encompassing focus that live theater required, when the show closed, Azar “escaped,” as she described it, to Israel.

“My father always said he could see that I was torn between worlds—that of theater and that of Israel and Judaism,” she noted. It was in Israel where she met Aaron, who was in rabbinical school at the time.

“He was the first person I met who was studying to be a rabbi,” Azar said of her hus band, with whom she has two daughters, ages 17 and 21.

Aaron comes from a line of spiritual lead ers. His grandfather, Hugo Chaim Adler, was chief cantor at the Haupt Synagogue in Mannheim, Germany, from 1921 to 1938. After immigrating to the United States, he became chief cantor for Temple Emanuel in Worcester, Mass. Aaron’s uncle, Samuel Adler, is a world-renowned composer and conductor, and his cousin, Naomi Adler, is CEO of Hadassah.

As for her role at Temple Emanuel, even though she divides her time between stage and synagogue. “I’m very involved,” said Azar. “I read Torah. I help organize this or that event. In that sense I’m a traditional rebbetzin.” —Curt Schleier

“It is contained in a beautiful, chased silver case much tarnished with age,” Mozelle writes.

A century on, those intricately embellished silver cases are on view in “The Sassoons,” perhaps as much a part of the family’s identity as any Sargent portrait.