5 minute read

A Journey Through Space, Time And Steep Wooded Climbs

By Lowri Watkins, Evidence Officer

Though Gwent may be small in area, it packs in some of the most spectacular landscapes and diverse habitats in the South Wales region. For millennia, glacial ice sheets, followed by the river itself, have carved out Wales’ ancient borderlands, leaving in their wake sheer cliffs, vast wooded valleys and dramatic gorges. In the centuries since, humans have left their mark too and the woodlands of the Wye Valley carry this rich history upon sprawling, moss-drenched boughs.

Advertisement

Croes Robert Wood, near Trellech, is just one of the enchanting woodlands that makes up this rich valley landscape and it just so happens to be a Gwent Wildlife Trust nature reserve. It sits within the Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), recognised for its broad-leaved woodland and dormouse population.

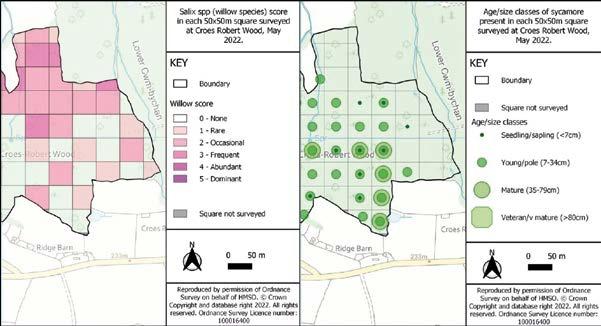

In May 2022, I headed to Croes Robert Wood to apply the ‘grid-mapping’ survey technique. This involves splitting the whole site into 50x50m squares, aligned with the British National Grid. Each square is traversed during the survey to record various features, such as the abundance of wildflowers or the age/size of the trees and shrubs. By applying a fixed grid, we can return to monitor variation in plants and habitats with greater detail and precision over time. This level of scrutiny can detect more subtle and gradual changes, and allow us to better relate these to the management. The ultimate goal is to create an effective monitoring-management feedback loop, giving us confidence that the action we take is having the desired results. And in looking after the plants and habitats, we build the steady foundations for all other life to thrive too.

“Enough pre-amble, Lowri! Tell us what you discovered”, I hear you say. Well, there were no real botanical surprises. As a SSSI, many finer botanists have come before me to study the flora of this magnificent site, so the species are quite well documented. That’s not to say there aren’t delights to be found, but the main aim of the survey was to map the finer detail. stood for centuries, important markers of ownership in the past. Some impressive older coppiced trees have also survived within the depths of the woodland, like the mammoth Ash tree in the photo [on the next page]. With a diameter of two metres, we could estimate that this tree is probably several hundred years old!

The woodland floor showcases a stunning assortment of plants, from spring favourites such as Wood Anemone and Lesser Celandine, to more localised curiosities, like Herb Paris (my favourite) and Moschatel. In places, Bluebells roll out in a crowded carpet, while elsewhere, lush, leafy Dog’s Mercury dominates, punctuated only by taller ferns.

In the understorey, Hazel is the most familiar sight, thanks to a long history of coppice management across this reserve. It is this ancient woodland practice which tends to promote the bright conditions for wildflowers to prosper. Birch, Rowan and Hawthorn are sprinkled into the shrub layer, creating further interest. Moving higher still, the canopy is dominated by the linear trunks of Ash, but wetter areas give rise to vast, arching Willows and bulky Alders.

The botanical mix shifts according to a wide range of conditions, with light levels, topology, drainage/moisture, and soil depth and pH all important factors. While we can’t really manipulate many of these environmental factors, our approach to woodland management can have a considerable impact on which plants flourish. We can, for example, influence how open or closed the canopy is, how the structure of woody species varies, and as a result, how much light reaches the forest floor. My survey hoped to identify some of this variation, by recording not only the different species of trees and shrubs, but their age/size too.

In winter, it was time for me to retreat to office work and set about analysing the wealth of information volunteer Paul and I had collected in spring. Cleaning and preparing the data can be boring, but it is all worth it when I finally get to visualise the results. It feels a bit like magic, importantly, it unlocks information about the condition of the woods and where our action is needed most.

We have a bit of ‘wish-list’ of features we want to see at Croes Robert Wood. Features which are key to ensuring a healthy, functioning ecosystem; one which can sustain a diversity of wildlife, from lichens to ferns, butterflies to birds and much more. The wish-list must provide for the Dormouse population too, which needs a succession of food throughout their active months (April – November) and well-connected woody layers to travel through.

WOODLAND WISHLIST

• A diversity of tree species as ‘standards’ and ‘coppice’

• Variation in structure, from temporary glades to dense thickets

• Natural regeneration of trees from seed

• Dead and dying trees

• Live trees with holes, hollows and rotten branches – great habitats for invertebrates, fungi etc.

• Diverse ground flora

The site has an interesting history, with most of the largest trees having been harvested for timber in 1982, just prior to GWT taking over ownership. As a result, some of the most mature trees survive only at the boundary, where they will have translating a spreadsheet full of numbers into a colourful map that instantly tells the story of the woodland. You can see snapshots of a couple of these maps [on opposite page].

From recording plant species, as well as their age/size, I can start to build a picture of where trees are regenerating, where the greatest diversity of wildflowers occurs or where the biggest, oldest trees stand. This is all really interesting, but more

One of the key outcomes of the survey work is to meet up with the Nature Recovery team over winter to discuss the results and make recommendations for future management. We have recently held this meeting for Croes Robert and it was really useful to bring together our different experiences of the wood. We chatted about the coppicing regime, how to control Sycamore regrowth, as well as more troublesome invasive species, such as

Cotoneaster. More detailed spatial plans can now be developed and we can return to the site in future to assess our success in implementing them.

A final note

It was such a privilege to visit all the hidden corners of Croes Robert Wood. Through my slow presence, I could feel myself falling in with the unique rhythm of the place, and noticing more and more. One of my favourite discoveries came in the shape of a beetle, rather than a plant. Volunteer Paul and I were trudging back uphill late one afternoon, when a little black blob began to cross the path in front of us. It was big and curious enough to warrant a proper inspection, so I gently scooped it up and allowed it to tiptoe over my hand. Up close, we could see it had an impressive arrangement of horns! It wasn’t a species I had encountered before, so we diligently photographed its many pleasing angles and set it down in the vegetation it had been heading towards.

Back home, I eagerly researched ‘big black beetle with horns’ and soon stumbled