20 minute read

Gwangju Now and Then: An Interview with Robert

24 Gwangju Now and Then An Interview with Robert Grotjohn

Interviewed by by Melline Galani

Advertisement

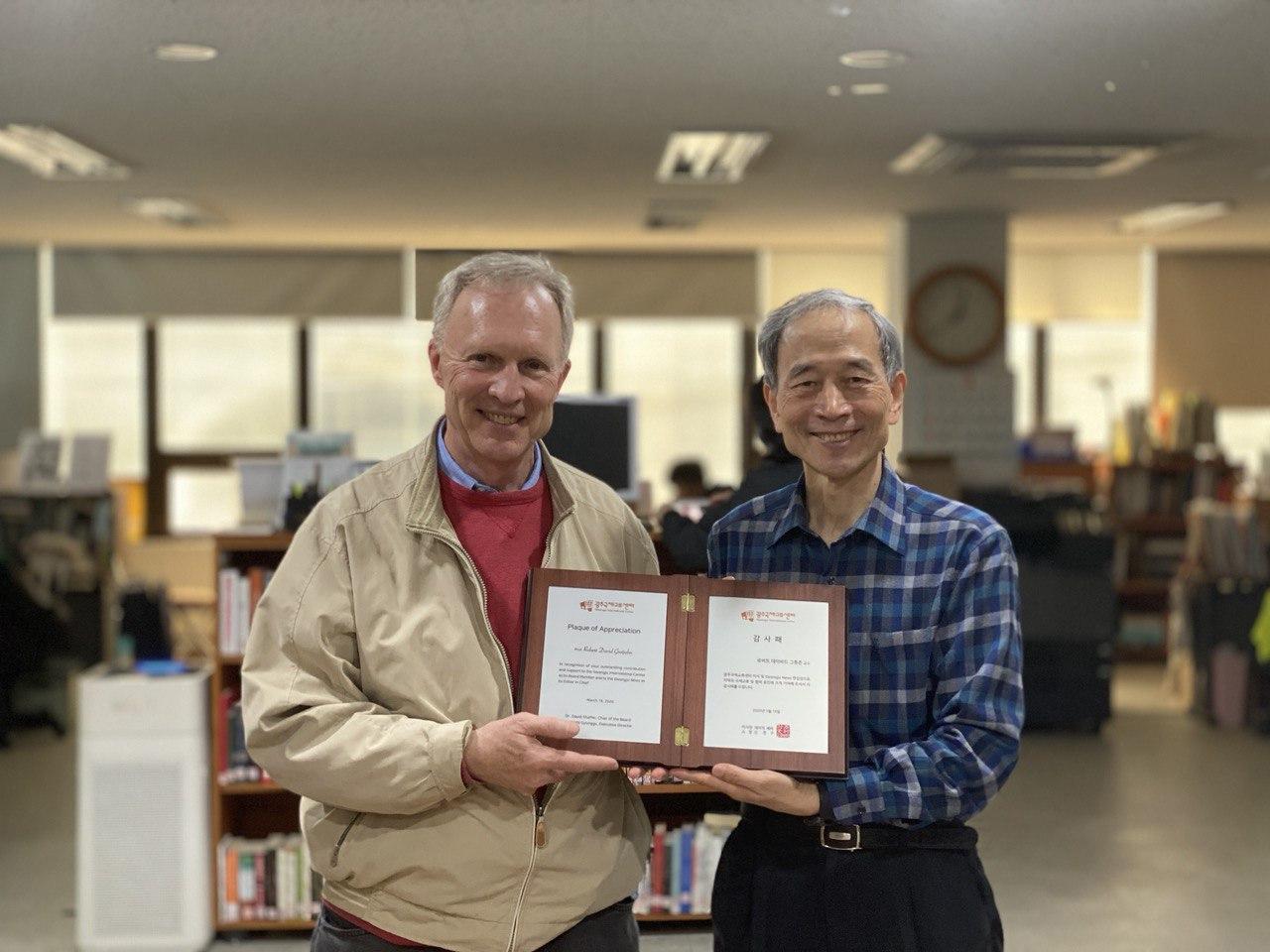

Dr. Shin and Dr. Grotjohn (right) saying their last goodbyes in front of the Gwangju International Center.

Robert Grotjohn has spent a considerable number of years living in Gwangju in two different decades – separated by a gap of twenty-five years! These disconnected experiences of Gwangju make Dr. Grotjohn a perfect person to ask to compare life in the Gwangju of the past with that of present-day Gwangju. Much of the following is devoted to this. Dr. Grotjohn’s involvement with the Gwangju International Center (GIC) has been considerable, including a period as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News as a member of the board of directors of the GIC. — Ed.

Gwangju News (GN): Let us begin with a selfintroduction. Could you tell us a little bit about yourself? Dr. Robert Grotjohn: I grew up in the small town of Brainerd, Minnesota. I attended university at the University of Minnesota, Morris, where I majored in English. I first came to Korea in 1981 to teach English conversation and composition to the sophomore English majors at Chonnam National University. While I was here, I was married and we had a son, born at the University Hospital and baptized at the missionary compound chapel across the street from Gwangju Christian Hospital. In June of 1984, I returned to the U.S. to study for my MA and PhD at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where I specialized in American poetry. While studying, my wife and I were blessed with a baby girl, an event that completed our little family of four. After a three-year position as a visiting assistant

professor at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, home of the legendary John Legend, I taught for 17 years at a small college in Staunton, Virginia – Mary Baldwin College, now “University.” In 2009, I returned to teach in Korea as a Fulbright lecturer at Chonbuk National University. While teaching there, I met with faculty members in the English Department whom I had known in the 1980s. One of those was Dr. Shin Gyonggu. Tenure-line faculty positions at Korean universities were first opened to international scholars in 2010, and I was invited to return to Chonnam University to teach American culture and poetry. So, I took early retirement from Mary Baldwin, and returned again in August 2010. I stayed until my mandatory-at-65 retirement at the end of February 2020, and I now live in Madison, Wisconsin again, where my son lives with his wife and two small children. I look forward to becoming a doting grandfather. GN: How were your first encounters with Gwangju and South Korea?

Grotjohn: My first personal encounter with Gwangju was in the summer of 1980. One of my college roommates had joined the Peace Corps and been assigned to Gwangju. He experienced the May 18 Uprising up close – if you have ever seen the photo of a Westerner in a plaid shirt walking alongside a stretcher holding a person injured in the Uprising, you have seen my old roommate, Tim Warnberg, a minor hero of the first days of the Uprising for rescuing a handful of injured people and helping them get to local clinics around Geumnam-ro. He was sent home to Minnesota that summer, and he spent a lot of time telling me and our other friends about his experiences in Korea, especially his traumatic experiences during May 1980. I remember his horrified description of the soldiers mercilessly beating an old woman who had been in the vicinity of the demonstrations, and his inspiring description of the taxi drivers’ charge on the soldiers at the Provincial Office Building.

Having grown up with images of protest in the Civil Rights and Anti-Vietnam War movements, images that inspired me to the leftish politics I hold still, I was deeply impressed by the willing sacrifice of Gwangju citizens in the struggle for democracy. When Tim returned to Korea and learned of the opening to teach in Korea through his Korean tutor, a graduate student in the English Department of Chonnam University, he asked if I was interested. I was, and I was hired. My first encounter with Gwangju, in other words, was in the storytelling of my friend Tim before I had ever set foot in Asia. My first experience of actually, or almost, being in Korea was on my first descent into Gimpo Airport – at that time, Incheon was most famous for MacArthur’s landing, not for its world-class airport. As the plane dropped in the fairly abrupt descent to Gimpo, I was struck by the colorful roof tiles of the houses – blue, red, and orange. Nowadays, tall buildings dominate the skyline of Seoul, but, in 1981, the most notable thing to me were the roofs of traditional houses. Indeed, when I made my way to Kwangju (yes, spelled with a K in those days) and took up residence in an apartment on the Chonam campus, I often took a morning run through a neighborhood that still had several choga-jib, the thatched-roof houses of old Korea, and no apartment buildings at all. A group of grandfathers sat in front of a small store every morning and would often offer me a raw egg to drink as I passed by.

▲ Dr. Shin (left) and Dr. Grotjohn (center) in a picture taken 40 years ago.

When I got off the plane and met Tim, who was waiting for me, we went out into Seoul. My first impression then was olfactory. Korea was still a developing country, and the smells were much livelier than those in the sanitized, underground-sewer and plastic-wrapped food of my limited Midwestern American upbringing. The traditional markets of Korea are still some of my favorite places to take in the smells of human activity. Another first-day reaction I remember is thinking, “I want to play basketball.” Because of the nutritional limitations of the post-war period in Korea, the average height of a Korean male was a few inches shorter than that of an American male. My height was just average in America, but in Korea, I was tall. When I returned in 2009, that was no longer the case; Korea had become fully developed, nutrition had improved, and the average height of a Korean male was about the same as that of an American male for the people who had grown to adulthood since my departure in 1984. American noses were also “taller” than Korean noses. It was not at all unusual in those early days to hear strangers refer to a foreigner as a ko-jaengi, a “big nose.”

When I first arrived in Gwangju, the semester was already several days old, as my visa had not been issued in time for me to arrive for the first couple of days. On the morning of my first class, about an hour before that class was to begin, I walked into the Chonnam Language Center, was introduced to the director, and was handed a textbook. “What should I do?” I asked. “Listen and repeat,” I was told. That is about what I did for the first semester, when I taught conversation to all the sophomore English majors. I became a more adept instructor in that sink-or-swim situation as the semesters progressed. GN: Could you please describe the difference between the Gwangju and Korea of the 1980s and what they were like when you returned? Grotjohn: I have already noted a few – height, houses vs. towering apartment complexes, aroma. Basically, Korea was just beginning to really explode as an economic tiger, and old Korea, like the choga-jib, was still an obviously essential part of Gwangju’s nature. In 1981, there was a lot of construction in Gwangju (that has not changed), and the materials were often brought to construction sites by horse-cart rather than by truck. By the time I left in 1984, trucks had replaced the horses in a concrete demonstration of economic development. I never saw a tractor in Honam, at least not to my recollection. The fields were all plowed by oxen. I remember once being struck by seeing a tractor out the bus window as I neared Seoul because I never saw one near Gwangju. The students were much more politically active. Every spring, the Chonnam campus would be filled with pepper gas as the students demonstrated for democracy. By 1984, I often heard “Yankee go home” as I walked through the campus, something that had never happened when I first arrived. Koreans had come to understand that the U.S., which they had imagined as a champion of democracy and human rights, had turned a blind eye to Chun Do-hwan and his military thugs, even given tacit approval for troop movements to Gwangju in May 1980. I did not resent it when people shouted at me. Rather, I sympathized with their anger and frustration, as well as their sense of betrayal. Had I been a Korean student, I may well have shouted at me as well. While the comments were not all negative, Westerners were open to frequent comments and greetings. One was always a remarkable presence in public, while nowadays, one is barely noticed. Other than Western missionaries, whom one rarely encounters these days, the white people living in Gwangju that I knew were the person teaching the sophomores in the English Education Department, two English teachers at Chosun University (one of whom was the venerable Dr. David Shaffer, editor of this magazine), and two German teachers at Chosun University. There may have been others, but I never met them. We were rarities and to be remarked upon wherever we appeared. One could not walk along Chungjang-ro without being invited to a tea room by someone who wanted to be your best friend in order to practice their English. There were many tearooms, the place one arranged to meet friends, and no coffeeshops at all. The only coffee was Korea’s famous mix coffee, which I am missing very much here in America. There was no pizza, no American fast food franchises. I was excited to eat at Korea’s very first McDonald’s and very first Pizza Hut, and I had to go to Seoul to eat at either. The society has become much more open to individual differences. While Korea still has some well-documented gender inequities, in the 1980s, women had little freedom to be individualistic at all. There is much more freedom to be oneself these days. There is much more openness about sexuality, for instance. In the 1980s, one would see men holding hands with their male friends but never with their female friends. Society was much more divided into gendered groups. Nowadays, “couple culture” is everywhere around us. Many more students are much better at speaking English than they were in the 1980s. Most of the students in my recent literature classes could follow the lectures and discussions pretty well. In the 1980s, it would have been a small fraction. Seoul was not so much the center of the academic universe in the 1980s. Many more good students stayed at their regional universities. Korean professional baseball had its inaugural season in 1982. The Haitai (not Kia) Tigers won their first championship in 1983, with many more to follow. I saw the first Tigers game at Mudeung Stadium in 1982 and their last game there in 2013. In the 1980s, we sat on the cold concrete. In the 2010s, there were seats.

Th e Gwangju International Center team bids farewell to Dr. Robert Grotjohn (front, center). ▲

GN: How did you enjoy your life and teaching aft er you came back to Gwangju in 2010? Grotjohn: Outside my family and my faith, my life and work in the 2010s were some of the greatest blessings of my life. I would make the same decision to return over again in a second. GN: How did you start working for the GIC and the Gwangju News, and how did you enjoy your involvement with them? Grotjohn: Dr. Shin, how else? When Dr. Shin [Gwangju International Center director] calls, I usually answer. He is my seonbae from the old days in Gwangju. When I fi rst arrived, I was much more involved, but life got busier and commitments more diversifi ed as I stayed here. I have been very happy with my experiences at the GIC. I learned a lot while editing the Gwangju News, including the fact that being an editor may not be my greatest talent. As the editor, and now as an interested reader, I was and am most impressed by the dedicated volunteers, both international and native, who make the magazine a production of which all Gwangju can be proud. GN: How did the GIC help you during your stay in Gwangju? Grotjohn: Th e GIC creates a comfort zone for the international community, whether or not an individual has much contact with the Center and its activities. It helps give the international community a feeling that Gwangju is home, and many have made it their home. Th e GIC gave me a foothold in the community outside the university, and that is very important in making the city become a home and not just a stopping point. If we did not have two grandchildren in the U.S., my wife and I probably would have stayed in Gwangju permanently. As I tell people who ask, “I want to stay in Gwangju, and I want to live in the U.S.” Th e GIC has been a signifi cant factor in creating those divided feelings. I am glad the GIC is here even though I have not spent as much time in recent years doing GIC things as I once did. GN: What are you planning to do now that you are back in the U.S.? Grotjohn: Go on a diet (this is not going well) – too many people took me to eat too much good food as we said our goodbyes, including my last culinary pleasures with Korean fried chicken with the staff of the GIC. I will miss the eating culture of Korea, and the food. I like to joke that I will start a Naju Gomtang restaurant in my retirement – not because I want to own a restaurant but because it is impossible to fi nd gomtang in most of the U.S., and I love my gomtang. I think I will dote on my grandchildren, read books, travel through the American West, fi nd a good Korean church so I do not lose my already limited Korean language skills. We almost decided to stay in Korea because as Korea has begun to get control of the coronavirus and pushed the curve downward, the virus is skyrocketing in America and the turn of the curve seems far too distant. Korea’s healthcare system looks better and better. Maybe the most pressing thing we can do in the U.S. is look for a way back to South Korea.

Photographs courtesy of Dr. Grotjohn and the GIC.

The interviewer

Melline Galani is a Romanian enthusiast, born and raised in the capital city of Bucharest, who is currently living in Gwangju. She likes new challenges, learning interesting things, and is incurably optimistic. Instagram: @melligalanis.

Odds and (Dead) Ends Spring Cleaning Edition

Written and photographed by Isaiah Winters

It’s time for a special spring cleaning edition of bizarre left over photos crowding my desktop. Like in the July 2019 edition of “Odds and (Dead) Ends,” these stories don’t quite pass muster as full articles individually, but together they don’t disappoint. I hope you share the same cornucopia of unwanted emotions I got when discovering them.

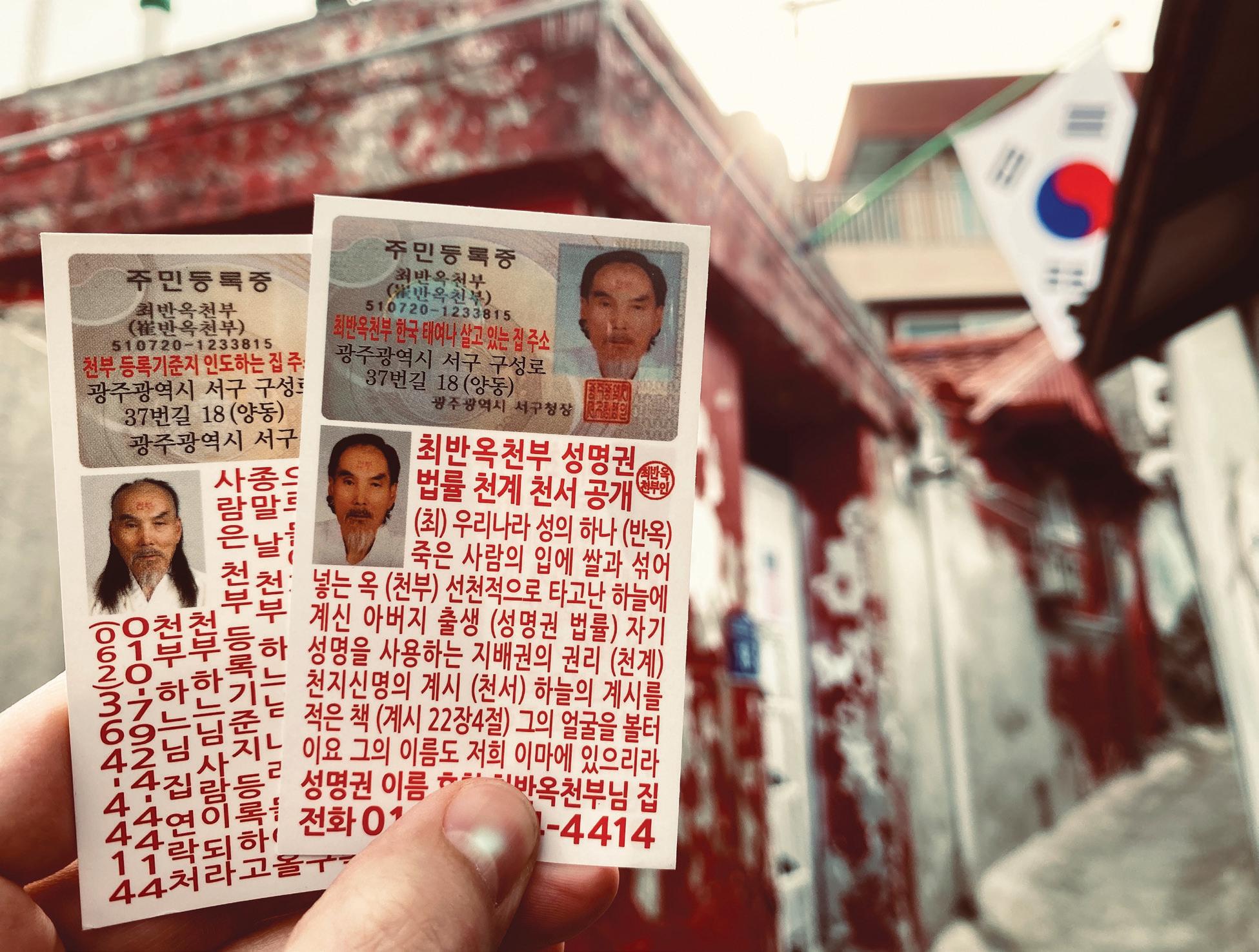

Th e New Testament (Yang-dong).

Th e New Testament (Yang-dong)

Gwangju’s very own “Heavenly Father” has updated his doomsday business card, and as his humble servant, I feel like it’s incumbent upon me to spread the news. Th e good news is that it seems there’s still time to avoid perishing in the rapture. You see, according to “Heavenly Father,” the Republic of Korea is possessed with evil demons

and sprits, so on a day of his choosing, the Earth will be destroyed and those who haven’t changed their addresses to the random rice fi eld addressed on the back of his new card will perish. Graciously, “Heavenly Father” has prepared a new world for all registrants, which I’m sure will come in handy. Th ere’s one major condition though: Th e world awaiting us unfortunately isn’t for people who

love money, so registrants would presumably have to forfeit their assets beforehand, though to whom I couldn’t possibly venture a guess.

The updated card from “Heavenly Father” bears more literary manna overleaf, and it couldn’t have come at a more opportune time. Apparently, if you want to be healed of any illness by his blessed hand, all you have to do is call the number listed – toll free! Now that such a trusty panacea exists, we can all get back to coughing in each other’s faces like it’s still 2019. I know I have. Speaking of faces, there’s one final detail I managed to divine from his New Testament card regarding why he has “Heavenly Father” (cheonbu, 천부) marked in red on his forehead. On one side, he quotes Revelation 22:4, which reads, “They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads.” It turns out that in New Jerusalem, God’s servants will actually be able to see him, and in a godly alternative to the mark of the beast, witnessing him will cause his name to be marked on their foreheads. I guess this means “Heavenly Father” has actually seen God for himself in New Jerusalem, which is all a bit confusing. If you’re similarly unsure who the real God is, then why not make the call and find out for yourselves?

Farmstead Kink (Samgeo-dong)

In one of the farthest-flung corners still technically within Gwangju Metropolitan City limits is an abandoned poultry farm with a kinky secret. In a garage adjacent to one of the farmhouses, I found a headless Santa Claus, a child’s spring horse, and a full-sized topless statue of a woman in a G-string. (Whichever you consider to be the kinky secret is your business.) Arms akimbo, the highly detailed and proportionate mannequin bears some resemblance to the original Wonder Woman, though with a darker complexion. I’ll never know what role this titillating effigy played on a farm otherwise strewn with poultry cages, asbestos paneling, and bird bones. The only detail I could glean about the owners was that they were Jehovah’s Witnesses (based on the panoply of religious materials from the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania found in the house). The stark cleavage between stacks of pious literature and a plaster temptress is another one of Gwangju’s many riddles, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

Farmstead Kink (Samgeo-dong).

A Watershed Moment (Yongyeon-dong).

A Watershed Moment (Yongyeon-dong)

It took a pandemic for me to acknowledge the gelatinous muffin top cascading over my beltline. So, with nothing but time on my hands for endless self-ridicule, I decided to skimp on lunches and go hiking five days a week, each time at a different spot. There’s a lot of good hiking within the city limits if you break routines and know where to go. For example, I’d always heard that there were waterfalls in Mudeungsan National Park, but I never bothered to seek them out until this spring. Pictured is the trail along Yongchu Falls, which is an easy hike (more like a walk, really) that crisscrosses the falls multiple times for almost three kilometers. The grand finale is a series of falls that, at least when I was there, was completely bereft of anyone but myself. A similar experience happened when I visited the far higher Shimujigi Falls on the backside of Mudeung Mountain – the only difference being that I didn’t see a single soul along the latter trail.

Interestingly, in the absence of hikers, regional wildlife has become braver. For instance, over the course of two separate hikes in nearby Jangseong-gun, I spooked at least seven deer in places where I’d never seen them before. (I got into a staring contest with two of them, but lost.) Similarly, the usual squirrels, mice, woodpeckers, and pheasants are all getting easier to spot, too. Eventually, I’ll probably run into wild boar as well and so always try to keep in mind which nearby tree might be best to climb if charged. Still, the region’s burgeoning wildlife presence is a nice respite from the herds of makgeolli-swilling sapiens and their techno-trot mating calls. Barring future pandemics, I don’t think there will ever be a better time than now to get out and explore our surroundings with as much serenity. Ultimately, like the reemerging wildlife, introverts like yours truly are thriving in this new environment.

Monumental Hate (Mudeung Mountain).

Monumental Hate (Mudeung Mountain)

“To the owner of this building: Don’t get conned by Messrs. Kim and Yun and their gang. Call the district architecture offi ce at 010-****-**** and ask. Don’t regret getting f**ked over.” Th is is the stern warning scrawled in red paint on the inner wall of this unfi nished building along the backside of Mudeung Mountain – an area I like to call the “dark side of the Mu.” It seems the “gang” referenced may have seen the message because someone later spray painted over its most sensitive details in red. Th e only reason the message can still be read today is because someone else (likely the original writer) returned and sanded off the spray paint in certain parts, especially where it mentions Mr. Kim’s full name. All this deduction suggests a vitriolic tit-for-tat playing out on the otherwise sleepy back slopes of Gwangju’s fairest mountain.

Eventually, these husks of rusted rebar and chipped concrete become monuments to so many untold stories of hate, debt, and bankruptcy. I’m fascinated by these overlooked disputes and all the rancor and fi nancial ruin left in their wake. In this case, the intended seven-story convalescent hospital remains forever stillborn and, according to a dingy signboard at the entrance, has had a lien on it since 2013. Nothing about the row seems to exist online, but the person who wrote the warning and the “gang” alluded to are nevertheless somewhere out there today with one hell of a story to tell about who owes whom what. Th ough admittedly morbid, my only hope is that whoever fi nally gets stuck with the debt doesn’t opt for felo de se.

Chairman Cha’s Death Beds (Yongsan-dong). ▲

Chairman Cha’s Death Beds (Yongsan-dong)

About two weeks before COVID-19 began to take off in Korea, I stumbled upon this defunct wedding hall with working electricity. Otherwise useless until demolished, each individual wedding hall within has been repurposed as a showroom for diff erent events, with the one pictured being by far the most unique. Lining the aisle where nervous brides once mincingly crossed into matrimony – with proud grooms in awe and all eyes moist with tears of joy – are rows of hospital gurneys that apparently served as seating for some macabre speaking engagement. Th e stage bore a banner welcoming Cha Jun-heon, pastor of the Work of Jesus Church and chairman of El Goal In pharmaceutical company. It seems he visited Gwangju last August for a seminar of sorts and, I guess, the gurneys were used as prop seating, maybe as a way to make the audience feel like they were sick and in need of Chairman Cha’s meds. His website slangs all sorts of detox products from soap and toothpaste to salt and water – and, of course, pills, pills, pills. Today the foyer of this particular wedding hall remains stocked with some of Chairman Cha’s merchandise under the banner, “In a low, humble manner of service.”

The Author

Originally from Southern California, Isaiah Winters is a Gwangju-based urban explorer who enjoys writing about the City of Light’s lesser-known quarters. When he’s not roaming the streets and writing about his experiences, he’s usually working or fulfi lling his duties as the Gwangju News’ heavily caff einated chief proofreader. And that’s how I’ll fi nish this overlong article, dear readers: in a low, humble manner of service.