25 minute read

Climate Crisis Response

ICEC, a Leader Towards a Sustainable Gwangju

Interview by William Urbanski

Advertisement

We are all aware of climate change, and we are aware that it is affecting the environment around the world, but are we aware of whether or how Gwangju may be affected? The Gwangju News has recently caught up with Dr. Yun Won-Tae, President of the International Climate and Environment Center, for an interview on the climate crisis and what is required to create a sustainable Gwangju

Gwangju News (GN): First of all, Dr. Yun, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Could you please tell us about your background, both academic and personal? Yun Won-Tae: Thank you for inviting me. I appreciate your interest in the International Climate and Environment Center (ICEC). It is a pleasure to introduce myself and my work to the Gwangju News’ subscribers. I grew up in the countryside and was always interested in nature; clouds especially fascinated me. This led me to the study of meteorology at the University of Cologne in Germany, where I earned my PhD.

Upon returning to Korea, I went to work for the national government as head of the Korean delegation to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate (UN IPCC) and later as president of the National Typhoon Center of the Korea Meteorological Administration. I have also worked with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as an expert advisor.

My family and I moved to Gwangju in 2019. Since then I have been serving as president of the International Climate and Environment Center (ICEC), secretary general of the Urban Environmental Accords (UEA), and professor of meteorology at Chonnam National University. In dealing with climate change and environmental issues in the city, I am focused on the strategic development of resilience and low-carbon sustainability of Gwangju. population resides in cities. Dense population in urbanized areas equates to heavy energy consumption and significant greenhouse gas production. So, cities are hot spots of vulnerability and exposure. Climate change calls for new approaches to sustainable development that take into account complex interactions between climate, social, and ecological systems.

Founded by Gwangju City in 2012, the ICEC was originally called the Climate Change Response Center. Later, when it was merged with the secretariat of the Urban Environmental Accords, the name was changed to the International Climate and Environment Center. For nine years, the ICEC has been committed to the vision of creating a sustainable Gwangju through vigorous efforts to research and develop climate change response policies, support green living among citizens, and realize a lowcarbon green city.

The ICEC has three basic goals: (a) developing and disseminating science-based technologies and policies for urban environments which, of course, includes Gwangju; (b) raising public awareness of the climate crisis and encouraging participation through inclusion and the education of local citizens; and (c) promoting knowledge-sharing and capacity-building programs via a global network of cities called the Urban Environmental Accords (UEA).

▲ President Yun Won-Tae

GN: Could you briefly explain the Urban Environmental Accords (UEA)? Yun: Simply put, the UEA is a promise. In June 2005, mayors from across the globe gathered in San Francisco for the United Nations World Environment Day. Sharing a common belief, city mayors voluntarily committed to implement and encourage city governments to adopt actions to realize the right to a clean, healthy, and safe environment for all members of society.

Currently a global collective of 156 member cities from 51 countries, the UEA continues to build upon and extend the efforts put forth by the signatory mayors. Through research, discovery, and development of innovative ideas and best practices, as well as various knowledge-sharing and capacity-building programs, the UEA endeavors to continually move forward to achieve long-term sustainability in our urban environments and beyond.

Through the UEA network, the secretariat shares ideas, opinions, and suggestions with member cities for sustainable urban development and promotes education to strengthen the efficacy of the city’s efforts. In collaboration with the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), the UEA recently launched a three-year training program. In October of last year, 25 civil servants of the Cambodian Central Government participated in the first of a three-part series on Sustainable Water Management via an online platform. In future sessions, we plan to expand and diversify the scope and content of the program.

Subsequent to the 2005 gathering, the 2011 UEA Summit was held in Gwangju and continues biennially, hosted by an elected member city, including San Antonio (Texas, USA), Iloilo City (Philippines), and Melaka (Malaysia). Next year it will return to South Korea, as the 2021 UEA Summit and Executive Committee Meeting and will be held in Yeosu.

GN: Could you further introduce some of the key programs of the ICEC? Yun: Sure. The world is suffering from extreme climatic events, and Gwangju is no exception. As annual average temperatures are expected to rise in the next ten years, extreme climatic events such as heatwaves, increases in fine dust particles, and heavy rains with flooding are expected to become much more frequent and severe.

In order to effectively adapt to and mitigate the effects of the climate crisis, information based on scientific analysis is essential to urban planning and environmental policy development. To this end, the ICEC developed and operates the Urban Assessment Model System (UAMS) and the Urban Carbon Management System (UCMS), both of which I will further explain in a moment. When analyzed, the data collected from these programs provide vital information for sound policymaking in fields of climate adaptation and response, as well as citizen-led initiatives. These tools are also made available to the international community via UEA networks and related organizations. In this way, Gwangju and the ICEC share their efforts in creating sustainable cities globally, helping cities around the world build their capacities for urban resilience.

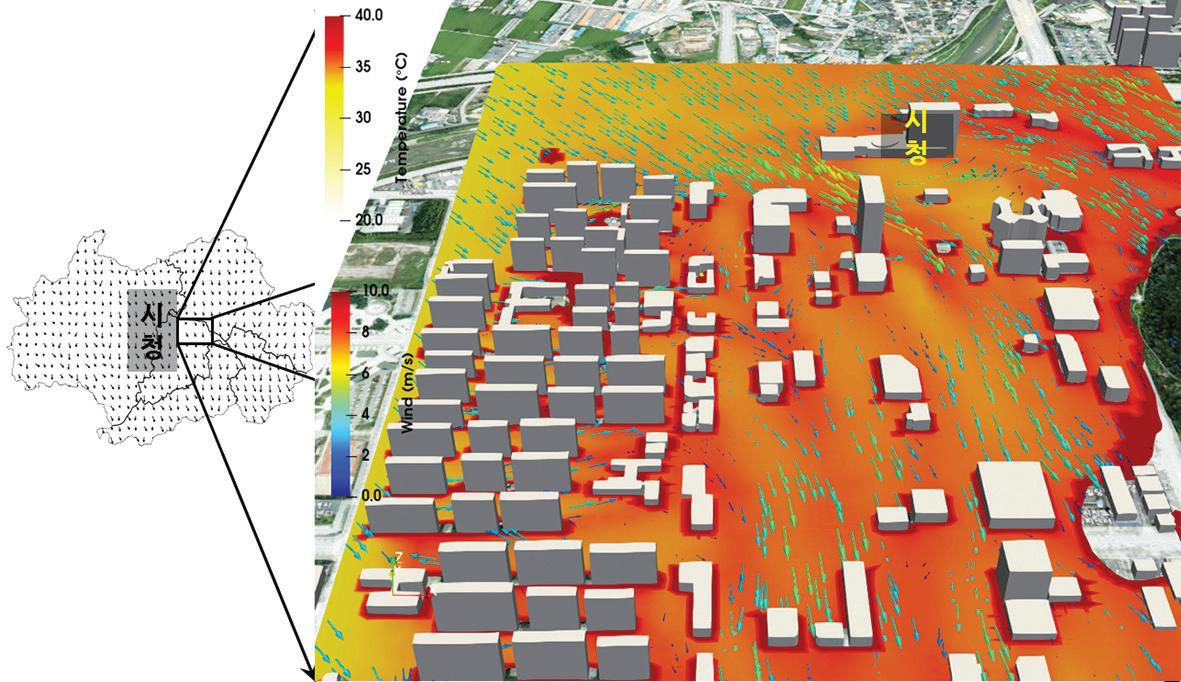

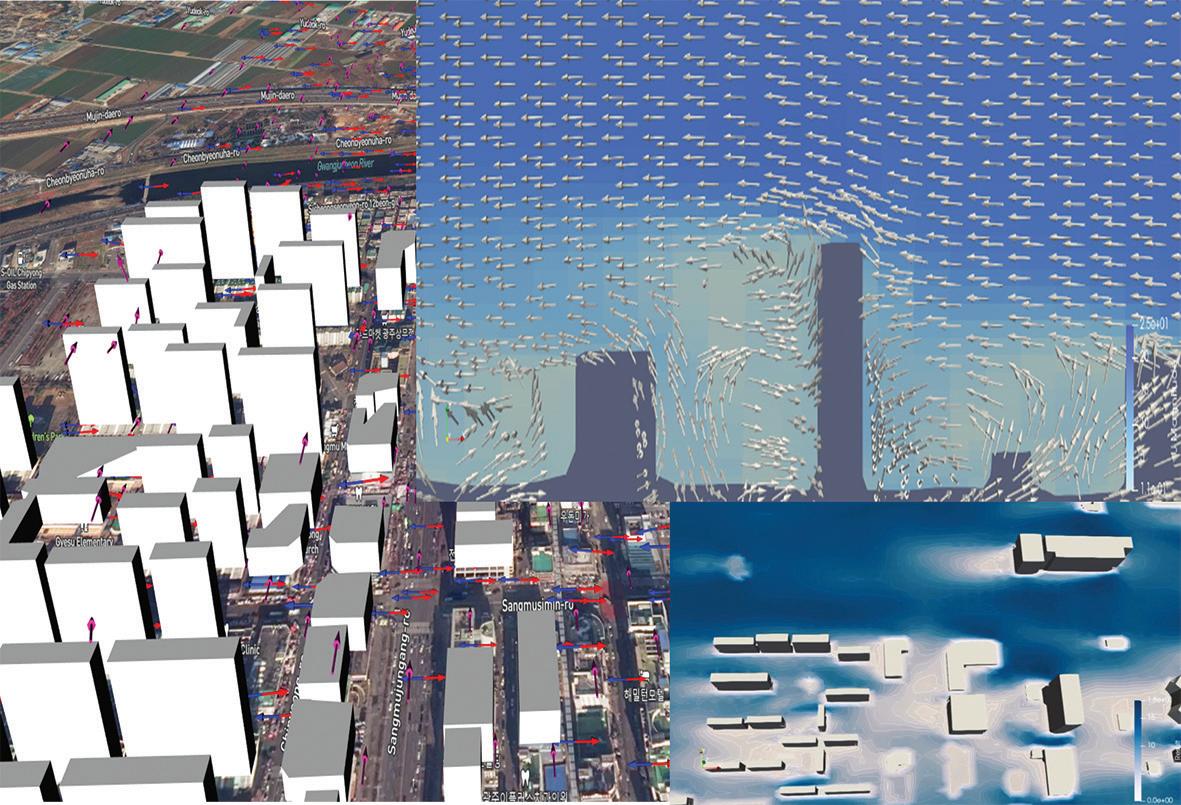

The Urban Assessment Model System (UAMS) is a three-dimensional, mathematical simulation model for calculating air flows, heatwaves, and fine dust dispersions in orographically structured terrain. The UAMS is suited for studying the climatic effects of local land use changes as well as for analyzing the climate of urban and suburban areas. The UAMS was developed to evaluate the environmental conditions within entire cities, providing information for decision-making in areas vulnerable to climate change, and it also helps to address the stratification of climate analysis difficulties.

The Urban Carbon Management System (UCMS) is used to regularly monitor and manage carbon emissions to facilitate the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) produced in urban and suburban areas. GHG reduction regulations are being strengthened worldwide, with the importance of urban-based GHG reduction gaining more attention. Recently, a number of countries and cities, including Gwangju, are making commitments to move to a net-zero emissions economy. This is in response to climate science showing that this is necessary in order to halt climate change. Net zero means that any emissions are balanced by absorbing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

The ICEC continually monitors carbon emissions in Gwangju and the surrounding metropolitan area. Establishing and employing the UCMS in the city, ICEC seeks to identify the characteristics of current GHG emissions to aid in the reduction of future emissions.

▲ Figure 1. Predicted temperature and precipitation in Gwangju (2021–2030).

GN: I feel a problem with the global warming dialogue worldwide is that it presents environmental problems (like large-scale greenhouse gas emissions) as such huge problems that it makes individuals feel helpless. What are your views on this, and are there things that individual citizens of Gwangju can do to lessen their negative impacts on the environment? Yun: In addition to administrative support (policies, regulations, etc.), public awareness is essential. Gwangju City and the ICEC continue to make their best efforts to encourage and support community participation through various projects. Sharing science-based information via education programs, special events, and campaign drives, the ICEC works directly with citizens to foster community instructors. Fostering instructors contributes to creating jobs in Gwangju, as well.

GN: Gwangju, as with most major cities, has substantial traffic, which causes a whole host of environmental and pollution issues. As well, some people just seem to be opposed to taking public transportation. Do you think there are initiatives the city could introduce (carpool lanes, for example) to reduce the number of cars on the road? Yun: A key factor in reducing the number of cars on the road is to provide efficient public transportation, specifically eco-friendly and user-friendly public transport. Construction of the second subway line began last year, and the first of three phases will be open in 2023, with phases two and three opening in 2024 and 2025, respectively. Currently, Gwangju has 37 electric buses and six hydrogen-powered buses in use. The city plans to build more charging stations and ramp up the hydrogen production base within the next couple of years. In the long term, Gwangju plans to realize 100 percent renewable energy for the bus system by 2030.

GN: Speaking of cars, I have been seeing more and more Teslas and electric cars on the road. Do you think electric cars are a good way to address the problems associated with car emissions? Yun: Yes, it is a good start. The argument has been made that electric cars are charged by energy produced at power plants that are burning fossil fuels. It is a valid point, but reducing the number of cars with internal combustion engines is the better choice in terms of overall energy efficiency and GHG emissions. However, in order for electric cars to have a more meaningful impact, the source of electricity must become environmentally friendly, such as solar and wind power. Gwangju plans to increase the generation of renewal energy needed to realize carbon neutrality. The transition to eco-friendly energy sources will greatly reduce GHG emissions in the vehicle and power-production sectors.

Figure 2. Results of CFD analysis of 3x5 kilometer area near Gwangju City Hall with grid spacing between 5–28 meters (analysis derived from UAMS data, 12:00, August 8, 2020).

▲ Figure 3. 3-D Analysis of the UAMS.

▲ Figure 4. Applied analysis on the climate Vulnerability-Resilience Index (VRI) in UCMS.

Figure 5. Analysis of GHG emissions in Gwangju using UCMS. This graph represents GHG emissions measured over the past ten years. Emissions in Gwangju have remained relatively steady since 2013, with the exception of noted increases in 2013 and 2018. Both events were attributable to the increase in energy use caused by heatwaves in the region.

environmental problems, especially with respect to Gwangju? Yun: To be clear, climate change is the most significant environmental problem humanity will face over the next decade, but it is certainly not the only one. Water shortages, loss of biodiversity, air pollution, and waste management are a few of the challenges we must address, as well. But it is important to realize that everything is interconnected, it is a circular ecology. Global warming due to GHG emissions is accelerating climate change, which is attributable to severe drought conditions and exacerbates water shortage problems. Poor waste management practices have catastrophically damaged our oceans, creating serious environmental issues that affect all life. The WHO estimates that 90 percent of humanity breathes polluted air, and the sources of air pollution are the same sources of GHG emissions. So, you are correct in noting that GHG emissions are not the only contributor. We should look at the entire picture and realize that each environmental issue is very much linked to the others.

GN: Discussions on pollution and global warming tend to focus on the doom-and-gloom aspects of climate and environment change. What are some positive changes or signs of progress that you have seen in Gwangju and around Korea? Yun: The whole world has been aware of the significance of the climate crisis. Armed with the knowledge that we must all act together, world leaders have made announcements of their plans for the coming years. They are making commitments to move to a net-zero emissions economy. Like most countries, Korea has declared that it plans to be carbon neutral by 2050. In line with these efforts, on July 21 of last year, Gwangju committed to becoming a carbon-free city by 2045 and announced the Gwangju General Plan for the AI-Green New Deal.

To prepare and roll out this plan, Gwangju is organizing a specialized support group this year. Led by the ICEC, this group will attract projects in related fields, make assessments on the performances of the projects, and help build community networks for citizen participation. In this way, the ICEC plays a key role in the realization of carbon neutrality and the Green New Deal of Gwangju. Thinking globally while acting locally, the UEA will aggressively work within its network to aid in mitigating further environmental damage.

GN: Thank you, Dr. Yun, for mitigating the gloom-anddoom fears that so many of us hold. It is immensely reassuring to know that Gwangju City and the ICEC are striving to alleviate the climate crisis and create a sustainable Gwangju.

Support the GIC! Be a Member!

The Gwangju International Center (GIC) is a non-profit organization established in 1999 to promote cultural understanding and to build a better community among Koreans and international residents. By being a member, you can help support our mission and make things happen! Join us today and receive exciting benefits! • One-year free subscription and delivery of the Gwangju News magazine. • Free use of the GIC library. • Free interpretation and counseling services from the GIC. • Discounts on programs and events held by the GIC. • Up-to-date information on GIC events through our email newsletter.

Annual Membership Fee

General: 40,000 won Students: 20,000 won Groups: 20,000 won per person (min. 10 persons) Inquiry: member@gic.or.kr / 062-226-2733

a Corrections to the January 2021 Issue Page 19: “Banking-Related Vocabulary” should have read “Online Shopping-Related Vocabulary.” Page 29: “Christina Lauren Wightman” should have read “Lauren Wightman.” The Gwangju News regrets the errors.

Ringing in the New Year… Again!

Korea’s Lunar Legacy

By David Shaffer

When I was young and growing up in North America, New Year’s was a special event. My parents and their best friends, who lived up the road, would get together on December 31 at either our place or theirs to spend New Year’s Eve. They would sit around the kitchen table to talk, joke, and gossip over warming cups of coffee and homemade cookies and cake. The evening would often involve the making of the annual eggnog, the traditional holiday drink, but the normally teetotaling parents also were known to occasionally, and clandestinely, spike their eggnog to make it a bit alcoholic. As the evening grew closer to midnight, everyone would gravitate to the television in the living room to watch the festivities in New York City’s Time Square, culminating in the big silver ball descending at the stroke of midnight.

When I came to Korea, I encountered a very different New Year’s: different foods, different customs, even different dates! If you did not get all the celebrating in that you had planned on in January, do not feel disheartened; Korea features a second New Year’s festivity three to seven weeks later every year! When I came to Korea, the first of these two holidays was called Sinjeong (신정, new New Year’s) and the later one, Gujeong (구정, old New Year’s). The more recent of the two holidays, Sinjeong, was created by the newly born Republic of Korea government after the colonial period. This was to show the world that it was not a backward country but instead was following the ways of the West, including celebrating the New Year according to the Gregorian calendar, on January 1.

Sinjeong is a one-day official holiday, while Gujeong, more commonly known as “Seollal” (설날) these days, is officially a three-day holiday. In recent decades, the existence of two New Year’s holidays has at times been hotly debated both by the general public and the government: Why should we have two New Year’s holidays; is that not illogical? If we keep them both, which should be the main one? In the process of this wrangling, the name of the lunar New Year has shifted: Seollal, or Seol (설), and Minsogui-nal (민속의 날, Folklore Day) during the latter 1980s when proponents of a single New Year’s day were strong.

▲ Eathly- God Ox

The Year of the Ox

This year, according to lunar calendar tradition, is Sinchuknyeon (신축년, shin-ox-year), which traditionally begins on the first day of the first lunar month – February 12 this year. And also according to tradition, this year is 4354 of the Dangun calendar, named after the legendary founder of Korea’s Gojoseon kingdom in 2333 B.C.

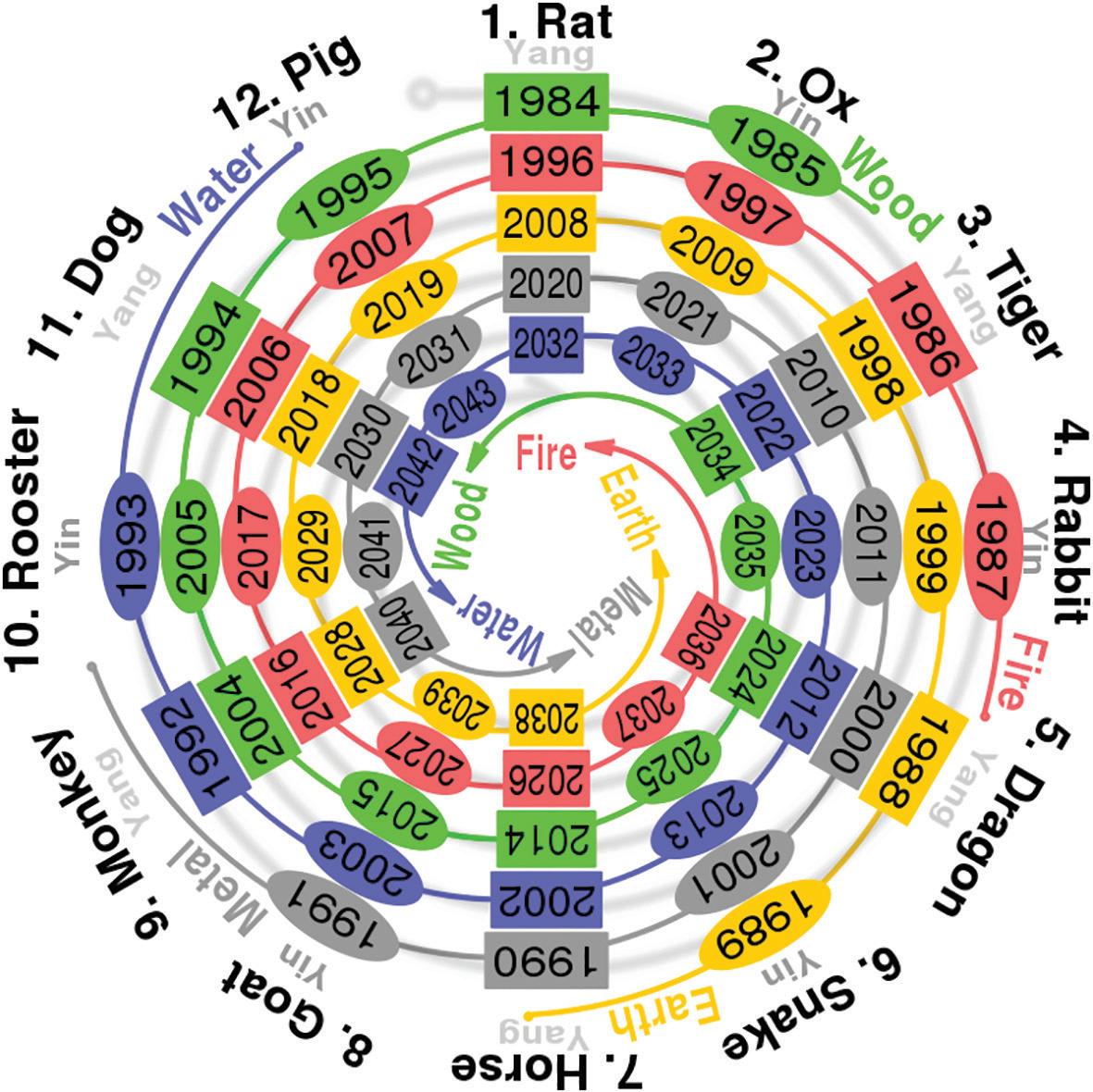

The name Sinchuk is one of the 60 names in the sexagenary cycle used in naming Korean years, which means that a year’s name repeats itself every 60 years. Each year’s name is composed of two parts: one of the 10 heavenly stems (cheongan, 천간), and one of the 12 earthly branches (jiji, 지지). Shin (辛) is the eighth of the 10 heavenly stems, combining with Chuk (丑, ox), the second of the 12 earthly branches. The 10 stems (let’s call them A–J) and the 12 branches (which we will number 1–12) combine linearly to create the 60 names of the years. For example, A1, B2, C3 … J10, A11, B12, C1 … J8, A9, B10 … and so on, until the cycle of 60 combinations is complete and begins to repeat itself. This year is also called the Year of the White Ox. Each year is associated with one of five colors (white, black, green-blue, red, yellow). The White Ox is said to bring good fortune (and after this past year, we sure could use it!).

Tradition grows deep roots, and Korea’s centuries-old lunar New Year’s holiday has most certainly survived and thrived, though how it is observed has in some aspects changed over the years. Performing ancestral rites is still a very important part of Seollal. Very early in the morning, the finishing touches are put on preparing foods for setting the table of offerings to the family ancestors – foods that family members may have spent most of the previous day preparing. This ritual, charye (차례), usually takes place in the home of the family head, who is the first son in the family line. The number of generations represented at the ritual table, often the five or seven most recently departed, depends on the customs of the clan that the family belongs to. Over the years with the spread of Christianity, this observance has moved from its original “ancestral worship” to paying respects to those who have passed on.

After the charye rites are completed and the extended family that has gathered at the home of the family head has eaten their breakfast, a mid-morning trek is made to the gravesites of one or more of the most recently departed family heads. Foods like those prepared for charye are packed for the trip into the hills, where the graves are often located. The gravesites may be quite a distance away, as they were often located on a hillside (determined by geomancy) in the vicinity of the family head’s home in the countryside. At the grave, foods are set out on a mat (rice, soup, rice cakes, meats, fish, and fruits, as well as a cup of alcohol) and ceremonial bows are made in the rite called seongmyo. Afterwards, the family members in attendance may have lunch with the ceremonial foods before their return.

Seollal Customs

Back in the family head’s home, children are awakening and getting washed and dressed for the day. They may be putting on their finest outfits or possibly their ceremonial hanbok (한복) in preparation for their requisite greeting to their grandparents and elders. This formal bow, sebae (세배, full bow with hands, head, and knees to the floor), was not difficult to get the children to perform because they knew that it included receiving a gift from those they bowed to, usually a gift of money, called sebae-ton (세배돈).

It is soon time for the children, and those staffing the kitchen, to have breakfast. On the menu is the traditional Seollal dish, tteok-guk (떡국, rice cake soup). The children were eager to finish the tteok-guk breakfast because they were told that they would become one year older if they did. Those most eager to up their age might have a second, or third, bowl of soup in the belief that one becomes a year older for each bowl of Seollal tteok-guk that they

▲ The sexagenary cycle for years.

dutifully devour. In the Korean age-counting system, everyone becomes a year older on the first day of the new year. This “new year” used to begin with Seollal, but as the importance of the Gregorian calendar has increased, becoming a year older on January 1 has now become the norm for most. So if you were born in, say, the year 2000, you would be 22 years old for all of 2021 (2000 is counted as year 1, 2001 as year 2, etc.). Though one celebrates their birthday, whenever that may be, they do not become a year older on that day.

On the wall of the kitchen, or another room of the house, it was not uncommon to see a pair of unused, freshly woven ladles made of rice straw. It was believed that if you bought a set of New Year’s ladles, known as bok-

▲ Sieve on wall awaiting the Yagwangi spirit.

jori (복조리, “happiness ladles”), they would bring good fortune to the household in the coming year. Bok-jori sellers once carried their wares from house to house on the eve of the new year, but more recently, one would have to go to the traditional market or another store to purchase bok-jori. It used to be a tradition in my family to add a new pair of “lucky ladles” each year to the collection hanging on the walls of the different rooms of the house. Sadly, this tradition discontinued as bok-jori have become more difficult to acquire.

Fun and Games

Lunar New Year’s Day, and the days surrounding it, has long been a time of solemn rituals but also of gaiety. The traditional Seollal entertainment most well-known today is the game of yut (윳), a board game played on a 30-centimeter rubbery mat with four sticks that serve as “dice.” The players are children with the adults coaching and cheering them on in the living room of the apartment. When I was younger and going to the countryside for Seollal, the game had a somewhat different appearance. The yut playing “board” was rolled out on the open area in front of the house – a large rice-straw mat more than a meter square with a large “X” inside a square drawn on it. The yut sticks were short, stubby wooden pieces, and the game was not for boys – the menfolk were playing and wagers were being made.

Yut was not the only game men would engage in. Inside the house, the hwatu (화투) cards would come out and the bets would be on. Hwatu, however, is not Seollalspecific; it can be played anytime three or more men get together and have a floor to sit on. The most popular hwatu game these days is probably go-stop (고스톱), though nationwide, min-hwatu was once the game of preference – except in the Jeolla area, where sambong (삼봉) was the signature game played with hwatu cards.

Fun and games are for the children, too. At this time of year, it is easy to find kite-making kits at stores. These fragile fliers are often assembled and destroyed by the wind in a single day. Kite-making and kite-flying (yeonnalligi, 연날리기) were once a more major undertaking. The kites were larger and sturdier, with intricate shapes and vivid designs on them. At the beginning of the new year, on a paper attached to the kite or written on the kite itself was the Chinese character for “misfortune” (厄, 액, aek). The kite was flown high into the sky, and the kite string was then cut for the kite to fly off and out of sight, taking with it all of one’s possible misfortune for the entire year ahead.

Jegi-chagi (제기차지), a game similar to hacky sack, has often been played over Seollal. The jegi (제기) is often a store-bought plastic weight with streamers extending from it – a colorful transformation of the homemade, cloth beanbag that was once the typical jegi that children would skillfully kick into the air for as many times as possible.

Just as popular as jegi-chagi was pengi-chigi (팽이치기, top spinning). The top was a stubby cylinder of wood, coming to a point at the bottom. The “spinner” was a handheld stick with a cord attached to one end to do the spinning when the top was properly struck. Much like jegi-chagi, pengi-chigi has given way to the much more sedentary games children now amuse themselves with on their computers.

On New Year’s night, special caution was required to guard one’s shoes, especially for the children. It was said that on this night, the night spirit Yagwangi would come to take the shoes that it liked. To prevent this, a large sieve was hung on an outside wall near the shoes because Yagwangi would be tempted to count the holes in the sieve. However, the sieve would have too many holes for Yagwangi to count before the rising sun would chase the night spirit away.

A Fortnight of Festivities

The lunar new year was traditionally not a one-day affair, nor the three-day holiday that it is today. Festivities spanned the 15-day period from the new moon of the new year to the full moon of the first lunar month: Daeboreum (대보름; February 26 this year). During this time, farmwork was put on hold throughout the entire village for the village folk to prepare and conduct numerous rites and village-wide games.

Individual families would hold household rites (antaek, 안댁) to appease the guardian spirit of the home and ward off disease, calamity, and misfortune for the coming year. Similarly, the village would hold a rite (dangsanje, 당산제) at the village tree to the village guardian spirit, which included farmers’ band music, dance, and offerings of food and drink.

A major undertaking in many villages was the weaving of a huge rope for the village’s tug-ofwar (jul-darigi, 줄다리기) in which the whole village was represented; the winning team was assured a good harvest in the coming year. Gossaum (고싸움) was a between-village competition involving two huge ropes used as battering rams to knock the opposing team’s commander off his rope perch, resulting in the certainty of a good harvest for the winning village in the coming year. Until recently, this was still held in Daechon-dong of Gwangju’s Nam-gu.

Th ough Daeboreum day was in the middle of winter, everyone was thinking ahead for good fortune in the year just beginning. Th is included keeping cool in the summer by “selling one’s heat” (deowi-palgi, 더위팔기). Children would wake up early to call out the names of others as if to get their attention. If the person replied, they had “bought” the caller’s heat. Be aware, this still may occur today, as older people remember of

Photo Credits

• Th e sexagenary cycle for years: By Cmglee, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86283295 • Sexagenary chart of year names: motioneff ect.tistory.com • Earthly-God Ox: Munsin-baekgwa • Yut board and sticks: Kokiri, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/ • Go-ssaum: Gwangju Daily News, http://www.gjdaily.net • Kite fl ying: Preservation Association of Korean Traditional Kite • Sieve on wall: Th e Academy of Korean Studies

it being practiced in their younger years. And then, fi nally, in the darkness of Daeboreum evening, folks would climb to an elevated area where they could get a good view of the Daeboreum moon, one of the two biggest and brightest full moons of the year. As the bright moon rose, solemn supplications were made to the orange orb for good health, good fortune, and other personal wishes for the year ahead. Th is year, I have prepared my own ahead of time.

새해 복 많이 받으세요 (Wishing you many New Year’s blessings).

Yut board and sticks.

The Author

David Shaff er is spending his fi ft ieth Seollal in Korea this February. He is the author of Seasonal Customs of Korea (Hollym, 2007) and has authored a years-long column on Traditional Korea in Th e Korea Herald. Dr. Shaff er is also editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.

Go-ssaum